Despite a 30-year process that has seen the return of democracy in Latin America, political institutions in the majority of countries in the region remain unconsolidated.Footnote 1 In the case of the judiciary, this deficit can be observed in the conflictive relationship between judges and political actors, in the absence of budgets that would permit improvements in the administration of justice, and in the job security of members of the constitutional courts.Footnote 2 As a result, the independence of judges to make decisions is not sufficiently strong to provide checks and balances or guarantee the rule of law, both essential prerequisites of a democratic regime. In consequence, the study of judicial–legislative relations or judicial–executive relations is generating ever more interest since a knowledge of the behavioural logic of the courts implies not only an understanding of that branch of government but also a better comprehension of democratic accountability in general. This raises two questions in particular that this article will address. Firstly, what factors explain why some judges vote with their convictions and others vote strategically? Secondly, why do some justices vote with their convictions despite making these decisions in a context of extreme institutional instability?Footnote 3 To answer these questions I analyse the case of Ecuador's Constitutional Court, whose justices face a high level of job insecurity, making it a paradigmatic example in Latin America.

In the following section, I review the principal findings of the judicial politics sub-field with an emphasis on the micro level. I then relate concepts and findings that have resulted from a long and rich tradition of research on judicial decision-making processes in the US Supreme Court. The third part puts forward a model of judicial choice, explaining the causal relationship between institutional stability and the conviction-driven or strategic nature of voting in the constitutional courts. This model argues that as institutional instability increases, judges show a greater proclivity to vote strategically but only up to a certain point, after which institutional instability actually creates incentives towards conviction voting.

In the fourth section I test the hypotheses derived from this theory, analysing the decisions made by 30 justices appointed to Ecuador's highly unstable Constitutional Court between 1999 and 2007. I begin by offering four case studies tracing the conditions of occupational uncertainty under which judges carried out their functions. I then use an independent measure of the judges’ ideological preferences and evaluate the content of their votes in a logistic regression to show that their political orientation strongly influenced their judicial decision-making. In the conclusion I discuss how, paradoxically, contexts of institutional instability constitute a fertile field for conviction voting by judges. Furthermore, I outline some basic theoretical and methodological ideas that could serve as the basis for future empirical research in the field of Latin American judicial politics.

Conviction-Based Voting versus Strategic Voting

Latin American political scientists have shown increasing interest in courts in recent years, yet little is known about the factors that influence judicial decision-making or the factors that affect judicial independence as a whole.Footnote 4 Although comparative research is best able to control for biases and establish higher-quality inferences, it remains a less popular approach than case studies.Footnote 5 The courts of Mexico, Argentina, Chile and Brazil are the most studied, while those of Central America and the Andean region have received less academic attention.Footnote 6

A number of different approaches to analysing courts have been adopted. One is to study the macro-level interactions between the judiciary and other political actors and from this infer the type of mutual controls that are generated between the branches of government and thus the quality of horizontal accountability. Another, using a micro perspective, focuses on analysing the individual votes of judges and establishing the factors that affect the orientation of judicial decisions. The unresolved debate in this second type of literature hinges on the variables that might explain why judges vote in accordance with their convictions or with strategic concerns. Following this approach, this article identifies the variables that explain why some judges follow their convictions despite making decisions in contexts of extreme institutional instability.

It is useful first to clarify the concepts of conviction and strategic voting. Judges cast a conviction vote when their decision reflects their pure ideological preferences.Footnote 7 The sincerity of this vote is apparent when judges cast votes independently of the machinations of their colleagues or of the variations found in the political environment. By contrast, judges vote strategically when their decision is influenced by the ideological orientation of actors not tied to the court, by media opinion, or by other factors. In this case, an individual judge's vote will depend not only on his or her own ideological position but also on the amount of pressure exerted by other actors.Footnote 8

Institutional stability, understood as the degree of job security granted to judges, is relevant to an analysis of judicial decision-making as its influence has been confirmed in studies of the US Supreme Court. This research shows that in the absence of fixed mandates and, most importantly, in the absence of threats to their tenure, justices vote according to their convictions.Footnote 9 Proponents of the attitudinal model and even those in the legal tradition therefore predict that judges cast their votes to mirror their political-judicial convictions as closely as possible.Footnote 10

The new institutional and separation-of-powers models concur that utility-maximising actors guide the judicial decision-making process, but they conclude instead that judges vote strategically.Footnote 11 For them, this behaviour derives from a principal–agent game logic implicit in the judicial dynamic.Footnote 12 As a response, adherents to the attitudinal models argue that even in cases where judges behave strategically in pre-trial motions, they vote with their convictions when the time comes to make a final decision. Although this debate is far from resolved, the attitudinal model is the one most convincingly demonstrated, at least empirically, in the North American literature.Footnote 13

This idea of the directly proportional relationship between institutional stability and conviction voting serves as the basis for the Latin American scholarship. Perhaps the most important work is Helmke's on the Argentine Supreme Court.Footnote 14 She argues that, faced with institutional instability, the justices’ principal worry is avoiding punishment and removal from the bench. As a result, they will vote strategically – that is, against the government that elected them whenever that government begins to lose power and political influence. Similarly, other work on Argentina shows that in political situations where the president enjoys a legislative majority sufficiently large to remove judges or increase the number of justices in the courts, conviction voting decreases. As judges sit for shorter times on the bench, there is an increased tendency for them to align themselves with those who hold political power.Footnote 15 In both cases, an unstable political environment motivates these actors to vote strategically.

Although Rebecca Bill Chávez's study on provincial Argentine courts in San Luis and Mendoza considers the degree of judges’ job security and the absence of dissenting opinions against the government as two of five constituent parts of the dependent variable she calls ‘judicial subordination to the executive’, her argument is consistent with that of Helmke and of Iaryczower, Spiller and Tommasi.Footnote 16 Indeed, it is possible to infer from this research that when judges are more likely to be removed from their positions due to a concentration of political power and an absence of multiparty competition, it is less likely that they will cast conviction votes. Research on the Mexican and German courts uses game theory to make the same argument: that judges vote according to their real preferences when they do not fear losing their jobs.Footnote 17 In short, the literature analysing the micro and macro levels of judicial behaviour agrees that judges will vote with their convictions when their jobs on the bench are more stable, and will vote strategically when they lack security of tenure.

However, it is possible to find an intermediate situation in which both conviction-based and strategic voting coexist. This occurs when, despite ruling in stable courts, judges vote according to their ideological preferences until their last months in office, at which point they start voting strategically in order to improve their chances of securing their next appointment, whether in the public or private sector. Although judges’ votes are being cast in response to a constellation of external political forces, this is not judicial instability in the strict sense. The Mexican Supreme Court and the Colombian and Peruvian Constitutional Courts are some empirical examples of this intermediate case.

Despite the clarity of the argument positing a causal relationship between the variables of institutional stability and conviction voting, this article argues that it is insufficient in at least two regards. The first issue is theoretical and relates to the absence of an explanation for an additional form of judicial behaviour in cases where, despite contexts of high job insecurity, judges do vote according to their convictions. In this instance, the influence of job insecurity on judicial relations has a different effect than that established in the literature, and is related to the price paid by political actors and judges for dismissing the justices of the constitutional courts.

The second objection is methodological and is related to two points. The first concerns the way in which scholars measure judges’ ideology independently of their decisions on actual cases, and the second is about the lack of an accurate yardstick regarding the political-ideological content of the cases on which they are ruling. As a result, the bulk of research undertaken on Latin America suffers from problems of endogeneity or inefficiency. Given these weaknesses, this article deploys an indicator of judges’ ideological ideal points that is independent of their actual voting behaviour.

Explaining judicial voting in contexts of extreme institutional instability

The dismissal of a judge or a whole court imposes costs on whichever institution has the power to interfere in the constitutional court. Regardless of whether the decision lies with the executive, the legislature or both, sacking and reappointing the members of a supreme or constitutional court is calculated in terms of the benefits that it brings to politicians. As other studies have shown, judicial instability can be explained by the executive's desire to appoint judges sympathetic to its own political agenda.Footnote 18 Nonetheless, the frequency with which courts are reshuffled is not the same across countries, implying that the differences can be specifically attributed to the costs generated by taking such a political decision.

In sum, political will influences not only the likelihood of an enforced turnover of judges, but also the price paid for doing so. Supreme court justices run a higher risk of being removed from office as the cost of sacking them decreases. Moreover, the reshuffling of a court not only benefits politicians who want to put in place like-minded justices, but may also boost politicians’ reputation, especially when public support for the judiciary is negative. This logic is visible in the wholesale sacking of Peruvian judges in 1992 following the ‘self coup’ decreed by President Alberto Fujimori, or the cases of instability observed in the Argentine Supreme Court in recent decades.Footnote 19

On the other hand, constitutional court judges must weigh up the costs implied in conviction or strategic voting with imperfect information about how secure their posts are. One scenario would see such judges voting with their convictions on the assumption that the political costs of removing them from the bench are so high that no politician would consider it. This guarantees a greater degree of judicial autonomy and a system of inter-branch checks and balances. In Latin America, this would apply to the courts in Brazil, Costa Rica, Chile, Uruguay and Colombia.Footnote 20 In this scenario as well as in the following, the degree of risk aversion – that is, fear of being punished with removal – is what determines the conviction-led or strategic nature of the judicial vote.

A second scenario sees judges voting strategically once the costs to politicians of sacking judges begin to decrease. In order to avoid being taken off the bench, these judges try to align themselves with whomever has the power to punish them. To save their own skin, they vote strategically by casting votes in line with the interests of the dominant political forces. Politicians derive specific benefits from such strategic judicial behaviour and prefer to avoid the cost implicit in removing these judges. This was the case with the supreme courts judges in Argentina and in Mexico during the rule of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Revolutionary Institutional Party, PRI).Footnote 21

The third and most interesting possibility occurs when the costs faced by politicians for replacing justices are equal to or approach zero. In these cases, politicians are always better off making new appointments of ideologically sympathetic individuals to top judicial positions. As these are cases of extreme instability, judges do not have sufficient incentives to vote strategically in order to keep their jobs. If the judges know that their removal is inevitable with a change in the configuration of political power regardless of how they vote, their most rational course of action is to rule on cases following their convictions. This allows judges to maintain or improve their prestige and reputation in the eyes of their fellow lawyers and, above all, in the eyes of their portfolio of clients to whom they will return as practising attorneys after being removed from the courts.

As a result, those who serve in highly unstable courts tend to be practising attorneys who temporarily accept the invitation to serve as judges in order to enhance their own professional prestige and that of their law practice. So while conviction voting is one of the positive effects of this scenario, the absence of career judges in these courts is one of the most harmful. Those who use the courts as an arena in which to build up their professional profile are here referred to as ‘judges without robes’.

In summary, this article sets out the theoretical argument that, contrary to conventional wisdom, the relationship between institutional stability and conviction voting is not linear, but is in fact curvilinear and U-shaped. Figure 1 shows how the probability of conviction voting decreases as stability decreases, although only up to the bottom of the U. At this point, a higher degree of uncertainty begins to favour conviction voting once again. While the first two cases described above have already been investigated, this article addresses the hitherto unexplored case of the judges without robes.

Figure 1. Relationship Between the Institutional Stability and Judicial Vote Variables

The proposed theoretical framework is innovative for three reasons. Firstly, it offers a specific explanation of a case in which, intuitively, judges are thought to vote strategically.Footnote 22 Secondly, it links a single conceptual framework to different empirical findings that have been used to analyse judicial voting patterns in Latin America. Finally, it constitutes a first attempt to apply the attitudinal model, strongly rooted in the North American tradition, to the Latin American political and judicial context.

This theoretical argument prompts a number of different hypotheses. The chief hypothesis deals with the link between conviction voting and institutional instability. Given the conditions of uncertainty under which they perform their roles, judges without robes should vote according to their ideological preferences. As such, judicial decisions can be understood as a result of the dilemma the judge faces in relation to the cases submitted for a decision, the legal tools at his or her disposal, and his or her own ideological values. Conversely, given that judges without robes are practising attorneys who are taking advantage of the judicial arena as a launch pad for their personal careers, it can be expected that they will return to their ‘natural habitat’ of private law practice once their functions on the court come to an end.

To test these hypotheses, this article analyses the case of the Ecuadorean Constitutional Court in the period 1999–2007. This is a good test case for the behaviour of judges without robes as it is one of the most unstable courts in Latin America. Ecuador's high level of party fragmentation, its permanent presidential crisis, and the formation of short-term and non-ideological legislative coalitions suggest that its Supreme Court should be one where we might expect judges to vote strategically.Footnote 23

Despite its particularities, the Ecuadorean case is not that exceptional in Latin America. In fact, job insecurity in the courts tends to be a constant across various countries in the hemisphere. The desire of politicians to count on ideologically like-minded judges is also part of the democratic life of the region.Footnote 24 Likewise, the presence of Supreme Court judges drawn mainly from private law practice is not unique to Ecuador, but is also found in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala. As such, the study of judges without robes in Ecuador is a first step towards a broader study of judicial behaviour in analogous contexts.

Finally, constitutional courts are an important object of study because it is increasingly common for them to decide on cases and disagreements emanating from the political arena. Court rulings on the constitutionality of a wide range of political decisions show how constitutional court justices have become political actors with the power to modify or invalidate previously agreed-upon public policies.Footnote 25

Instability as a Modus Vivendi of Ecuador's Constitutional Court

Faced with the need to create a system of constitutional control, and following the path taken by Colombia (1991), Peru (1993) and Bolivia (1994), Ecuador implemented legislative reforms in early 1996 that gave birth to the country's Constitutional Court (Tribunal Constitucional del Ecuador).Footnote 26 However, legal and political complications prevented the court from functioning until the first quarter of the following year. Later, the 1998 Constitution wholly ratified the court's attributes and functions; this lasted for a little more than a decade, until the 2008 Constitution eliminated this court, converting it into the so-called Corte Constitucional. In short, the main difference between the Tribunal Constitucional and the Corte Constitucional is that the first had power only to decide whether a law was constitutional or not, while the second has the additional power to interpret the law and create specific jurisprudence. This article is concerned solely with the life of the Constitutional Court as constituted and operating during the period 1999–2007.

From a judicial perspective, the fleeting existence of the Constitutional Court in Ecuador's republican life illustrates the constant turnover of actors and legal norms surrounding the country's political decision-makers. This, in addition to the constant disregard for the term length established for the court's judges, is ample evidence for considering Ecuador a case of political uncertainty, judicial insecurity and, in broad terms, institutional instability.Footnote 27 Under such conditions, combined with the basic weakness of the judicial power vis-à-vis the executive and legislative powers, the ‘natural’ behaviour for Constitutional Court judges would be to cast their votes based on the political environment in order to avoid being removed.Footnote 28 However, it is precisely this extreme institutional instability that made Ecuador's court a paradigmatic case of judges who vote with their convictions, despite their job insecurity.

Between 1999 and 2007, none of the Constitutional Court's judges finished the four-year term to which they were elected. Although impeachment was the only mechanism available to dismiss them, all of the removals took place on the margins of this legal process. Even the threat of impeachment was not entirely credible, due to the high level of party fragmentation. In fact, the resulting competition in the legislature during the period analysed makes it difficult to attribute the constant restructuring of the court to any single actor. As a result, it was temporary agreements between parties of different ideological stripes that made the removals possible.

Knowing this history, judges might have assumed that such instability was an innate trait of the administration of justice and learned to behave according to this restriction. The average survival length for each configuration of the court was only 20.75 months, with June 1999 to March 2003 (46 months) and December 2004 to April 2005 (four months) being the longest and shortest periods of stability respectively.Footnote 29 As a corollary, once party agreements resulted in the removal of the Constitutional Court, judges left their positions without any type of appeal. Although the context of each episode of removal varies, the differences in ideological orientation that brought about the falls and the facility with which they took place point to the minimal costs of removing justices. The following section details the four episodes of wholesale court removal. In order to reconstruct these events, I use newspaper reports, interviews with actors involved, and an analysis of the legislative bills used to remove the judges.

March 2003: The end of the PSP–Pachakutik alliance and the Febres Cordero–Gutiérrez agreement

On 9 January 2003, shortly before the beginning of President-Elect Gutiérrez's administration, the legislature designated two new judges to represent it on the Constitutional Court, despite the fact that the sitting judges’ term was set to expire only months later, in June 2003.Footnote 30 A majority of 54 deputies, composed of the Partido Social Cristiano (Social Christian Party, PSC), the Izquierda Democrática (Democratic Left, ID), Democracia Popular (Popular Democracy, DP) and the Partido Renovador Institucional Acción Nacional (Institutional Renewal Party of National Action, PRIAN), declared that as of that moment, the members of the Constitutional Court had surpassed their term limits.Footnote 31 This agreement initially excluded the governing Partido Sociedad Patriótica (Patriotic Society Party, PSP) and Pachakutik, as well as the Partido Roldosista Ecuatoriano (Ecuadorean Roldosist Party, PRE), independent deputies and other minority party representatives.

The decision not only paved the way for the total restructuring of the Constitutional Court but also represented the first political defeat for the incoming government. With this precedent, PSP and Pachakutik members reached an agreement on 19 March 2003, using the formation of a ‘mobile majority’, to designate the remaining seven magistrates.Footnote 32 On this occasion, they were joined by the ID, the PRE and the small parties that had been excluded on the first vote.Footnote 33 This was how the first Constitutional Court in Ecuador was systematically removed, just months before the judges were to complete their first full term. Despite the arbitrary nature of the legislative resolution, none of the judges resisted the decision or filed legal appeals.

November 2004: The Gutiérrez–Bucaram agreement and its effects on the Constitutional Court

By mid-2004, the Gutiérrez government had ended its electoral alliances with Pachakutik (in November 2003) and with León Febres Cordero's PSC (in February 2004). As a result of this and the approaching local elections of 17 October, the PSP forged a new political pact in July 2004 with a number of political forces, including the PRE.Footnote 34 While the government needed greater legislative support to approve a package of bills aimed at economic reform, the PRE aspired to bring its party leader and founder, ex-president Abdalá Bucaram, back from exile in Panama.Footnote 35

Within this new political framework, and following a failed attempt to impeach Gutiérrez by the PSC, the ID, the Movimiento Popular Democrático (Democratic People's Movement, MPD) and Pachakutik, PRE deputy María Augusta Rivas managed to muster sufficient support to restructure a number of judicial bodies, including the Constitutional Court.Footnote 36 On 25 November 2004, after a negotiation process within and between the candidate-nominating bodies (the legislature, the executive, the Supreme Court, and workers’ unions, mayors, prefects, and Chambers of Commerce), the constitutionally appointed judges were removed from the bench scarcely 20 months after being designated.Footnote 37 As in the previous case, their exit was peaceful and without mishap.

April 2005: The fall of Gutiérrez and constitutional limbo

President Gutiérrez was removed from office on 20 April 2005, amidst corruption scandals, wide-scale social protest and legislative hostility. Consequently, agreements reached with the PRE and other parties to restructure a number of judicial bodies, among them the Constitutional Court, were left without sufficient political support.Footnote 38 As party alliances changed (now spearheaded by the PSC and ID) and Vice-President Alfredo Palacio assumed power, the legislature approved a resolution on 26 April invalidating the designation of the new Constitutional Court judges who had been appointed just five months earlier.Footnote 39 Just as before, the outgoing judges did not contest this decision or issue any type of appeal protesting the unconstitutionality of their removal. On the contrary, a few hours before the legislative resolution took effect, some of them let it be known that they were willing to put their posts at the disposal of the legislature.Footnote 40 Despite protests and measures taken by judicial officials opposed to the judges leaving the bench, the Constitutional Court was thus restructured for the third time in fewer than six years.Footnote 41

In addition, one week prior to the removal of the constitutional judges, the legislature had made a similar decision on the Supreme Court judges, in office since 8 December 2004, ruling that the new judges should be chosen through a public merit-based competition.Footnote 42 In this complex ad-hoc procedure designed by the legislature, it was not until the end of November 2005 that Ecuador again had an active Supreme Court.Footnote 43 Given that the appointment of the bench in the Constitutional Court depended in part on the Supreme Court sending two three-candidate lists to the legislature, the new Constitutional Court judges were not designated until 22 February 2006.Footnote 44 In sum, President Gutiérrez's fall caused not only changes in the country's political and judicial configuration but also the absence of constitutional justice for almost a year.Footnote 45

April 2007: The rise of Rafael Correa and his impact on Constitutional Court stability

Rafael Correa was elected president on 26 November 2006, after winning the presidential run-off against the coastal businessman Álvaro Noboa with an anti-party and anti-politics discourse. The new head of state assumed power against a backdrop of high popular expectations and one principal objective: the convocation of a Constituent Assembly.Footnote 46 After a number of failed attempts due to the domination of the legislature by opposition forces, the president was finally able to get the Tribunal Supremo Electoral (Supreme Electoral Court, TSE) to call a plebiscite on 1 March 2007 and thus fulfil his main campaign pledge.Footnote 47

As a response to Correa's victory, a legislative majority comprising the PSP, PSC, DP and PRIAN voted to file a lawsuit in the Constitutional Court claiming the TSE's decision to be unconstitutional and asking for the removal of the president of the TSE, Jorge Acosta, and the impeachment of the other four judges who ruled in favour of the decision.Footnote 48 The TSE's response was swift: on 7 March, it decided to strip all 57 of the deputies who supported the legislative resolution of their seats in parliament.Footnote 49 With the majority of seats now in the hands of the replacement deputies, it was not hard for the government to negotiate the necessary support, creating the ‘Congreso de los manteles’ (‘tablecloth congress’).Footnote 50 With these changes in the balance of political power, the resolution removing the constitutional judges was only a matter of time.

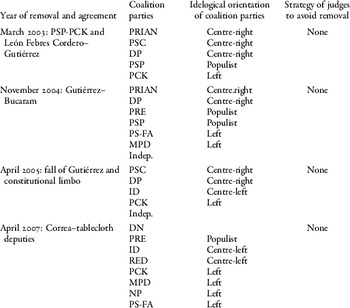

Despite the adversity of the situation, six Constitutional Court judges decided to accept a lawsuit presented by the expelled deputies on 23 April 2007, and ruled in favour of the reinstatement of 50 of the 57.Footnote 51 The following day, a majority made up of the stand-in deputies (‘los diputados de los manteles’), together with the ID, PRE, MPD, Nuevo País (New Country, NP), Partido Socialista–Frente Amplio (Socialist Party–Broad Front, PS-FA), Pachakutik, Red Ética y Democrática (Ethical and Democratic Network, RED) and various other small groupings, passed a resolution stating that the Constitutional Court judges’ terms had expired on 7 March 2007, and that they had to be removed, and new judges chosen.Footnote 52 Thus, only a year after taking office, the members of the Constitutional Court were once again relieved of their positions. As on the other occasions, once this legislative resolution was issued, the judges left office without putting up a fight.Footnote 53Table 1 summarises the ideological orientation of the political actors who intervened in each of these episodes, showing that all political parties, without exception, were responsible for the instability in the Constitutional Court.

Table 1. Legislative Coalitions in the Removal of Constitutional Court Judges (1999–2007)

Sources: El Comercio, El Universo, Hoy, legislative acts from the National Congress. Author's elaboration.

Conviction Voting and Decision-Making in Ecuador's Constitutional Court

This section offers a quantitative analysis of the conviction-oriented or strategic nature of the Constitutional Court judges’ votes. The units of analysis are the 529 individual judges’ decisions in cases of judicial review (control abstracto de constitucionalidad, CAC) whose content is related to (1) the degree of state intervention in the economy and (2) the level of flexibility in regulating employee–owner relations. These suits were selected because their objective of overturning previously agreed public policies provides the most ‘political’ arena over which Constitutional Court judges make rulings. Furthermore, given that ruling over judicial review lawsuits is one of the few activities undertaken by the full court, composed of nine judges, it is easier to analyse the individual judges’ votes when they act in a collegial context. Finally, the selected judicial review rulings have social and political relevance as they affect the entire population and are not susceptible to being overturned by any other body.

These two types of judicial review topics were selected as being the ones best placed to reflect the ideological positioning of the court's judges. Since economic opening and labour flexibility are at the centre of the discussion about structural adjustment in Latin America, they most accurately pinpoint the position of the judges along an ideological–spatial spectrum. The information in the database used here comes from a larger collection of data by the Carlos III University of Madrid and from research in the Constitutional Court archives.

This article considers the relevant decisions of 30 Constitutional Court judges between 1999 and 2007, which allows an evaluation of the different configurations of the court as well as possible changes in the content of the judges’ votes from the time they took up their posts until the time they were fired. The first cohort of judges (1997–9) is excluded from the analysis due to the incompleteness of the available information and because there was not yet much clarity regarding the admissibility criteria for judicial review requests. The last cohort to hold office in the Constitutional Court, from mid-2007 until 2012, is also excluded due to the low number of judicial review cases (25) ruled on before the application of the 2008 Constitution, which would not permit a robust quantitative analysis.

The dependent variable: The ideological content of judges’ votes

The individual decisions of all 30 judges are analysed to construct the dependent variable. I have coded a dummy variable expressing the ideological inclination of each vote, where ‘1’ corresponds to a left-of-centre vote and ‘0’ to a right-of-centre vote. As the institutional design regulating the Constitutional Court requires judicial review lawsuit rulings to be made only in favour of or against the constitutionality of the disputed law, the range of options is restricted to only two possibilities, making a dummy variable the most methodologically viable option.

To operationalise this concept, I assumed that a left-of-centre vote is one that favours (1) greater intervention of the state in the economy and (2) greater legal restrictions on liberalising labour relations. Votes in the opposite direction are recorded as right-of-centre. The measurement corresponds to the total number of times that the judge voted, leaving aside absences and cases in which an alternate judge cast a vote.Footnote 54 For those judges who sat in the court for more than one term, the assigned values correspond to the total number of decisions.Footnote 55Table 2 summarises how the judges’ votes have been categorised in terms of ideological tendency.

Table 2. Ideological Content of Constitutional Court Judges’ Votes (1999–2007)

Source: database of decisions from CAC cases. Author's elaboration.

A first finding shows that, overall, the ideological slant of votes was largely to the right. Specifically, 60.5 per cent of the decisions supported the liberalisation of the economy and the labour system (n=320), while 39.5 per cent were left-leaning (n=209). Following this article's theoretical proposition that constitutional judges vote according to their ideological preferences, the results of the dependent variable should correspond to a greater number of judges ideologically oriented towards the right. Lastly, and contrary to popular belief, the differential between the left-of-centre votes and right-of-centre votes (21 per cent) is not sufficiently large to support the idea of any type of predominant ideological position within the Constitutional Court.

The principal explanatory variable: Judges’ ideological preferences

The following analyses whether Ecuador's constitutional judges decided on cases according to their convictions or strategically under contexts of extreme labour instability. Given the reluctance of judges in constitutional courts in general to place themselves on an ideological scale, and above all due to the biases that this measurement may generate, the evaluation of their preferences requires alternative methodological strategies.Footnote 56 One option is to analyse the orientation of their rulings on certain topics in order to infer the ideological orientation of each judge. However, this would result in a circular logic by which judges’ ideological position was both the cause and the effect of their votes. This violates the assumption of conditional independence and leads to a problem of endogeneity where the independent variable is derived from the dependent variable instead of being its cause.Footnote 57

Other forms of measurement include analysis of the content and slant of judges’ votes prior to the period under analysis, identification of the party affiliation of legislators who nominated them, and analysis of public speeches or sentences.Footnote 58 However, these strategies do not overcome the problem of endogeneity, nor are they practicable due to the absence of roll call voting in the Ecuadorean legislature until 2009, party atomisation, and the resulting alliances between parties in order to nominate candidates. In addition, since not all judges have previously published declarations or papers published in specialised journals, analysis of those texts that have been published would violate the principle of unit homogeneity.

The principal methodological contribution of this article is therefore the creation of an index of judges’ ideal points, completely new to Latin American study.Footnote 59 For this, I relied on a survey administered to various actors who, by virtue of their profession and/or institutional placement, are familiar with the Constitutional Court and its judges in different ways. Those consulted included lawyers, academics, politicians, judicial officials, representatives of not-for-profit organisations and members of the media.Footnote 60 Since the case selection is non-random, I surveyed people of different ideological stripes, geographical locations (Quito, Guayaquil, Cuenca and Loja) and professional fields in order to avoid further bias. I conducted a total of 110 surveys, divided proportionally among the aforementioned groups.Footnote 61

The Ideological Placement Index (IPI) is made up of three indicators. The first evaluates the judge's viewpoint on the degree of intervention the state should have in the economy, the second evaluates their view on the desirable degree of liberalisation of labour relations, and the third captures the location of each judge on a left-to-right ideological scale. Each indicator is constructed as an ordinal variable with a range of 1 to 10. A value of 1 corresponds to judges on the left who are absolutely opposed to economic and/or labour openness, while a value of 10 is allocated to judges on the right who fully support economic and labour market liberalisation. To construct the IPI, the median is taken for each of the three indicators, and the median of those three values is then taken. Table 3 summarises judges’ ideological preferences measured in this way.

Table 3. Ideological Location of Constitutional Court Judges

* The range is from 1 (extreme left) to 10 (extreme right).

Source: Ideological Placement Index for judges. Author's elaboration.

Of the 30 judges under analysis, two-thirds are ideologically right-of-centre and the remaining ten are left-of-centre. This, when combined with the number of left-leaning and right-leaning votes cast by the judges, reveals a directly proportional relationship between the two variables. The ideological median of the Constitutional Court over the period studied was 5.99, which confirms that the decision-making political power in the court was distributed around the central ground.Footnote 62 The relative rarity of ideologically extreme positions corroborates this argument.

In addition, the IPI has been constructed in such a way as to make it applicable to other countries, and most importantly, its features have been obtained in a form independent from judicial voting. Still, the surveys were administered after the judges’ terms, which could potentially cause the respondents to rationalise their answers as a function of their previous knowledge of the content of the votes cast.Footnote 63 To evaluate this possible bias, I also obtained an alternate measurement of judges’ ideological inclination taking the spatial location of the parties affiliated with each judge as a proxy: I included a question on the survey asking the respondents if they associated the judge with any of Ecuador's political parties.Footnote 64

After this, I assigned each judge the value that Coppedge (with his Mean Left-Right Position (MLRP) index) and Freidenberg (in the Parliamentary Elites of Latin America project, PELA) awarded the parties in their respective studies.Footnote 65 To test the IPI's robustness, I ran a correlation analysis between this index and each of the alternative measurements.Footnote 66 I first standardised the IPI data in relation to the MLRP data, since the IPI and PELA data are already measured along the same scale. The results show a strong correlation between the IPI and MLRP (0.824) as well as the IPI and the PELA results (0.869). These coefficients support the proposition that, overall, the IPI values are robust and capture the judges’ ideological preferences with an acceptable level of confidence. Although there are inevitably some problems of endogeneity in the measure, there is no strategy for measuring judges’ ideological preferences that offers a higher degree of accuracy. Table 4 indicates the percentage of those surveyed who agreed in their identification of each judge's ties to a party.

Table 4. Correlation between Constitutional Court Judges and Party Affiliation According to Expert Surveys (1999–2007)

Notes: PSP: Partido Sociedad Patriótica; DP: Democracia Popular; PSC: Partido Social Cristiano; PRIAN: Partido Renovador Institucional Acción Nacional; PRE: Partido Roldosista Ecuatoriano; ID: Izquierda Democrática; MPD: Movimiento Popular Democrático; PS-FA: Partido Socialista–Frente Amplio; PCK: Movimiento Pluricultural Pachacutik.

* In the case of Judge Orellana, the ‘Other’ category corresponds to the Movimiento Nuevo País (New Country Movement, NP).

Source: surveys taken in the cities of Quito, Guayaquil, Cuenca and Loja in 2007. Author's elaboration.

Some alternative explanations

I also included control variables considered in the specialised literature in order to test this article's theoretical proposition against alternative explanations, the first and most important of these being the possibility that judges align their votes with the majority party in congress. To do this, I used Coppedge's data to record an ideological preference point for each political party. Next, I reconstructed the distinct legislative majorities formed as coalitions between 1999 and 2007, identified the median party in each of these, and recorded the ideological preference point of that median party.Footnote 67

The second control variable deals with the importance of the norm that is being subjected to judicial review. The literature indicates that judicial behaviour can depend on the degree of relevance of the legal decision under review.Footnote 68 I coded for a dummy variable taking into account the importance of the norm as a function of the degree of negotiation and the number of intervening actors. This variable is coded ‘1’ for organisational and general laws, since they involve interaction between the executive and legislative powers and have the highest impact in terms of public policies. The rest of the laws are coded ‘0’ if they have more limited reach (provincial or municipal) or are supplementary and are decided on by only one level of government. This group includes ministerial agreements, regulations, and municipal and provincial bylaws.

The third alternative explanation measures whether the substantive issue being addressed by the lawsuit under consideration influences judicial voting, as some of the literature suggests.Footnote 69 To control for this, I constructed a dummy variable in which those cases focused on the degree of state intervention in economic matters are coded as ‘1’ and those cases linked to the degree of labour openness are coded as ‘0’. These subjects were selected because they most accurately reveal the political position of the judges involved.

The last control variable deals with the ideological position of those filing the lawsuits and any possible repercussions this might have on the judges’ votes. This is coded as a dummy variable identifying the ideological preference of the plaintiff, using the content of the lawsuit as a proxy. I coded a left-wing litigant as ‘1’ based on a lawsuit seeking to overturn a public policy that would decrease state intervention in the economy or increase labour liberalisation; likewise, I coded a right-wing litigant as ‘0’ based on lawsuits that seek to overturn a policy of greater state intervention in these areas.

A model explaining conviction voting in contexts of institutional instability

I ran three different logistic regression models to test the hypothesis and estimate the relative impact of the above variables on judicial voting. Of these three, model 3 is used for the final analysis based on the significance of its parameters and its model fit. In model 1, which includes all of the variables discussed, mean legislative party ideological location does not have a statistically significant impact on judicial voting. Furthermore, political factors related to the possible influence of legislators on the judicial decision do not appear to cause variation in the voting behaviour of judges.

However, since the formation of a new legislative coalition may also cause judicial turnover and the appointment of an ideologically close group of judges, it is possible that the judges do not even have the opportunity to vote strategically. Of course, if the change in ideological location of the median coalition party member causes the designation of new judges, the ideological distance between the legislature and the Constitutional Court would disappear immediately. Although this could be considered an alternative interpretation of the results, it really just confirms this article's argument that in contexts of extreme institutional instability, judges have no incentives to vote any other way than with their convictions.

Essentially, if changes in the ideological orientation of the legislative coalitions did not result in the removal of Constitutional Court judges, the political context would not be that discussed here, one of high uncertainty. Of course, if the goal is to assess how judges vote when the balance of political power has shifted and the cost of removing the judges is not zero or close to zero, this becomes a case of strategic voting, as proposed in the scholarship on Argentina, or conviction voting, as proposed for the US Supreme Court. In the end, these three cases fit into the theoretical proposal and show a U-shaped relationship between the institutional stability variables and judicial voting.

In addition, according to model 1, normative arrangements are a variable that also has a non-statistically significant effect on voting. In other words, the judges do not use selective criteria in the process of making decisions. Despite the fact that the legal pronouncements made by the judges vary in regard to their degree of negotiation and number of intervening actors, this factor appears to have no impact on judicial voting. Conversely, the rest of the explanatory variables show statistically significant results, although the ‘ideological preferences’ variable has the most important relationship to the content of the votes. The substantive issue under review and the ideological position of the claimants also exerts an influence on the dependent variable when the distances are sufficiently large.

Model 2 drops the ‘importance of the law submitted for judicial review’ variable. Generally this has little effect on the degree of overall significance of this model compared to the previous model, leading to the elimination of this variable as well as that of the median legislative party. The following analysis therefore focuses on model 3, since it contains the most significant parameters. For ease of interpretation, I adjusted the model to express the coefficients as log-odds ratios. Table 5 presents the statistical results of the three models.

Table 5. Three Models to Explain the Judicial Vote in Contexts of Institutional Instability

* p<0.05.

** p<0.01.

*** p<0.001.

+ e^b=EXP(b)=factor change in odds with a one-unit increase of X.

+ + e^bStdX=exp(b*SD of X)=change in odds with a one-standard-deviation change in X.

Results

The negative sign produced by the coefficient related to ideological preferences confirms this article's hypothesis. However, to identify which of the independent variables with statistically significant values has the greatest weight in the selected model, I evaluated the standard error for each. The effect of the variable is greater when the deviation is close to 0, while the effect is smaller when the deviation is greater than 1. Importantly, the weight of the ideological preferences variables (0.36) on the content of the judicial vote is much greater than that of the variables related to the issue submitted to review or the ideological position of the plaintiff (0.70).

Although the other variables maintain a certain level of significance, the judges’ ideological preferences variable is the factor that best explains the voting decisions made by the Constitutional Court judges. The analysis of the most extreme left and extreme right judges illustrates this. According to the model, holding all other independent variables at their mean, the judge located at the far right ideological value of 7.57 (Jacinto Loaiza) has a 15 per cent probability of voting to the left, while the farthest-left judge, with an ideological preference point of 2.14 (Lenín Rosero), has a 91 per cent probability of voting in this direction. Figure 2 shows a graphical representation of how the probability of casting a left-leaning vote decreases as the judge's ideological preferences move towards the right.

Figure 2. Probability of a Leftist Vote According to a Judge's Ideological Placement

To support these findings, I also calculate the marginal effects of the coefficients. These show that small variations in the median ideological location of the judges cause notable changes in the content of their votes, especially when these actors are located farther to the left. The impact of a one-point increase in the ideological preference point of a judge (that is, movement to the right) decreases the probability of casting a left-wing vote by 18 per cent. Conversely, as a judge moves closer to the left, the probability that he or she will cast a vote in this direction increases considerably.

Following the coefficients given by model 3, the ideology of the plaintiff and lawsuit issue variables have negative and statistically significant effects on the content of the votes. In terms of marginal effects, a plaintiff located on the left of the ideological spectrum reduces the probability of a judge casting a left-wing vote by 17.9 per cent. This finding is understandable, and supports this article's argument that since two-thirds of the judges are ideologically right-of-centre and they vote with their convictions, lawsuits filed by left-of-centre actors will have a lower probability of being reviewed favourably.

The content of the cases under review also has a measurable impact on the direction of voting. Cases of judicial review dealing with the degree of state intervention in the economy decrease the probability of a judge casting a left-wing vote by 17.9 per cent when all other variables are held at their mean values. This finding reveals not only the selective criteria of judges at the moment of casting votes, but also the lack of absolute coherence in the ideological position of these actors. This is also consistent with findings from Grijalva in his own work on the Ecuadorean Constitutional Court.Footnote 70

Although variables related to the subject under review as well as characteristics of the plaintiff have an influence on the orientation of the votes cast by the Constitutional Court's judges, their own ideological preferences constitute the most important factor in motivating their vote choice. Thus we see how a combination of institutional instability and extreme job insecurity creates propitious conditions for judges to cast conviction votes. Table 6 displays the variables’ marginal effects from model 3.

Table 6. Odd-Logs and Marginal Effect for Model 3

+ e^b=EXP(b)=factor change in odds with a one-unit increase of X.

+ + e^bStdX=exp(b*SD of X)=change in odds with a one-standard-deviation change in X.

y=Pr(success)=0.38.

Tracing the professional careers of judges without robes

If the judges without robes vote with their convictions despite, or because of, their job insecurity, what are the potential benefits of this behaviour? Here I argue that the main objective of the judges without robes is to strengthen and increase their fields of professional activity as well as their client portfolios. While their appointment to the court constitutes an essentially symbolic distinction, the most important material returns will be earned after their time on the bench. In other words, given the conditions under which constitutional justice is practised, those who take up a position on the Constitutional Court do so as a means of consolidating their professional activity.

To test this proposal, I analysed the judges’ professional careers before and after they served on the court. This methodological strategy is useful for a number of reasons. For one, it identifies the different groups of professionals that dominated the different cohorts. Secondly, it permits inferences regarding the relationship between conviction voting and its consequences for judges’ professional futures. The career paths of Constitutional Court judges before and after serving on the court are derived from material in the chief newspapers in Ecuador: El Universo, El Comercio and Hoy. I also consulted with interviewees on key information in order to control for possible biases originating in these sources.Footnote 71 All cases include information from the two years prior to the judges serving on the court and the two years subsequent to it.Footnote 72 This enabled me to standardise the period of study, allowing for an easier comparative analysis.

The professional careers variable is operationalised as a set composed of two analytical categories. The first includes the judges whose activities were directed towards private law practice. The second considers actors involved in university lecturing or those who lent their services to other areas of the public sector, including the judiciary. In cases where individuals were involved in more than one of these activities, they were coded according to the activity to which the individual dedicated the most time and energy. With these two analytical categories, it is possible to compare the ex ante and ex post professional careers of the judges through a comparative matrix.

Analysis of results

Given the conditions of job insecurity, only some of the lawyers who meet the formal requisites to sit on the Constitutional Court are actually motivated to participate in the selection process. From this perspective, those lawyers with a private practice developed and consolidated over a long period of time are those most likely to assume a position marked by uncertainty and instability. Thus, given their lower degree of risk aversion to being removed, private practice lawyers have constituted a large portion of the court's judges. This is illustrated by Table 7, which shows that 22 of the 30 Constitutional Court judges (73.33 per cent) came from this sector.

Table 7. Professional Trajectory of Lawyers Before and After Serving on the Constitutional Court (1999–2007)

Sources: El Comercio, El Universo and Hoy, and key interviews. Author's elaboration.

Supporting the ‘judges without robes’ argument, 72.72 per cent of all lawyers who worked in private practice before serving on the Constitutional Court returned to the same activity afterwards (16 cases). This evidence confirms not only that the judges viewed the Constitutional Court appointment as a transitory event, but above all that conviction voting is the best strategy in the relative absence of ambition and incentives to remain on the bench. In other words, judges without robes who had worked as private attorneys took up the post for personal strategic reasons, but then voted according to their convictions.Footnote 73 This logic also illustrates that successive Constitutional Court judges learned from the behaviour they observed in their predecessors.

Finally, an additional consequence of the asymmetric distribution of judicial posts between judges without robes and career judges centres on the absence of sentences that set some significant judicial-political precedent. Essentially, given that judges without robes take up their court posts for instrumental and professional reasons, the decisions they then make may amount to a mere superficial resolution of the cases without greater judicial argumentation. Research directed at the analysis of the quality of judicial decisions and the influence of this variable on the composition of the courts is essential to understanding the unwanted consequences of judges without robes in greater detail.

Conclusions

A nearly consensus view in the field of judicial politics holds that job insecurity among Constitutional Court judges is a decisive variable in determining if the votes they cast are informed by conviction or strategic concerns. The specialised literature empirically confirms this, arguing that as institutional stability (that is, respect for judges’ term lengths) decreases, so too does the likelihood of judges voting with their convictions.

This article challenges that theoretical conventional wisdom by demonstrating that the relationship between these variables is actually curvilinear. An increase in institutional instability provides judges with greater incentives to vote strategically, although only up to a point of extreme uncertainty, which thereafter incentivises them to vote with their convictions once again. Using this theoretical argument, this article explains not only why judges rule on cases with their convictions despite working in contexts of high institutional instability, but also the other cases described in the literature.

This article also makes a methodological contribution. The strategy used here to capture judges’ ideological preferences is unknown in the region and is the most accurate, avoiding some possible biases left unresolved in the literature by measuring and constructing the ideological preference variable independently from the judges’ votes.Footnote 74 Nonetheless, future research should incorporate further dimensions to this variable.

Additionally, the description of the judges’ professional careers supports the coherence of the ‘judges without robes’ argument. Essentially, if job insecurity provides incentives for conviction voting, it also provides incentives for private practice lawyers to take up posts in the Constitutional Court instead of as professional jurists. This means that the court has come to be seen as a space in which to earn benefits of a symbolic nature, whose fruits are borne out in the medium or long term through an increase in the portfolio of clients and, in general, greater prestige for the law offices to which the judges without robes belong. An undesired effect is that this instrumental vision damages the quality of decisions made. We also see judges learning from the logic observed in their predecessors’ actions.

In addition, the results raise some questions related to judicial independence, an important element in the survival of democratic regimes.Footnote 75 Although this article has shown, paradoxically, that it is possible for judges to vote with their convictions despite being vulnerable to removal by political powers, this does not mean that such a context is therefore one of high judicial independence. While strategic or conviction-led voting is considered a measure of this concept, the type of relationship between low and high court judges and the influence of illegal payments to influence decisions are other aspects of judicial independence that remain to be analysed.

This article has made it clear that not all judges sit in the high courts with the desire to remain there for a long period of time. There are some who, despite insecurity of tenure, opt for this position because it is the best way for them to improve their professional careers outside of the high courts. Following this path, voting with their convictions is the best strategy that the judges without robes can hope to pursue.