The fourteenth of April of 1906 marked the founding of a new Carnival dancing society called Flor do Abacate (Avocado Flower) in Rio de Janeiro, the capital of the Brazilian Republic.Footnote 1 Its social profile was not very different from that of the dozens of other organisations like it founded in the city during the first years of the twentieth century. Born of the broad associative movement which saw new societies dedicated to dance and Carnival sprout across the city year after year, in a phenomenon that many contemporaries described as ‘dancing fever’,Footnote 2 the club was made up of labourers like José Roberto Monteiro, a civil construction worker, and Joaquim Machado, who worked in a garage.Footnote 3 Not only was its social makeup similar to that of many other small dancing clubs established in the period, Flor do Abacate was likewise of modest means, with a ‘humble’ headquarters, ‘as one of its directors acknowledged upon receiving a newspaper reporter’.Footnote 4 In the eyes of another journalist of the period, this was yet another ‘workers’ society’.Footnote 5

One characteristic, however, helped to set Flor do Abacate apart from some of the other associations of its ilk: the considerable number of negros and pardos in its member base.Footnote 6 While this was hardly surprising, given the large proportion of Brazilian workers of African descent at the turn of the twentieth century, a few photographs taken in February 1911 at a dance held at the club, later published by the Revista da Semana (Figure 1), illustrate just how strongly this was manifest in the members of the society.

Figure 1. Flor do Abacate – Carnival Group, Singers – Management Committee, Orchestra.

Elegantly dressed, the members of the club, some of them holding musical instruments, presented themselves similarly to many other societies of the same type. Striking a staged pose in photographs that they themselves had insisted on taking days earlier, to pique the interest of O Paiz,Footnote 7 they arranged themselves before the photographer's lens, projecting an image that affirmed a sense of order and discipline to rival that of their wealthier peers. In the case of Flor do Abacate, however, these images make it clear that almost all of the society's members would be easily categorised as negro by the newspaper's readers. This was unmistakably a society formed by workers of African descent, though not exclusively so.

Nevertheless, the photo also makes it clear that the members of Flor do Abacate presented themselves in a manner quite unlike that adopted by other Carnival associations. Since the last decades of the nineteenth century, some, like the Cucumbis and other groups which paraded down the streets during the days of Carnival, had taken their supposed African heritage as the basis of their identity.Footnote 8 However, the negro and pardo workers who made up the membership of this club distanced themselves from this model – with its evocation of a primitive Africa – by which the historiography generally explains the recreational, music- and dance-related world of the Cariocas (natives of Rio de Janeiro) of African descent. Indeed, much of the work on the cultural life of Rio de Janeiro in the period assumes the existence of a profound chasm between the cultures of the negro and pardo residents of the city and those of the lettered world, then dominated by a cosmopolitanism of European extraction encapsulated by the idea of a ‘tropical Belle Époque’.Footnote 9 Even studies that pay greater attention to the relationships and exchanges between these cultural universes reinforce the existence of this rigid cultural barrier, separating Afro-descendant cultures from the lettered world. They characterise the adoption by negros and pardos of the ‘standards, tastes and demands’ valued by the mainstream press as a simple artifice by which they might ‘aspire to higher degrees of recognition and legitimacy’, the product of ‘strategies’ by which they ‘tested the new social rules in place in the wake of Abolition and the Republic’.Footnote 10

Such studies affirm an idea of a cohesive, articulated negro culture with its own logic and interests entirely at odds with those of the elites, a culture that may be lost altogether or negotiated in one way or another by its bearers. This betrays a somewhat totalising, organic conception of the cultures and identities forged by Africans and their descendants in republican Rio de Janeiro, sprung from the survival of fundamental cultural traits that would set those of African descent apart from their peers. Though some studies have underscored the limits of this cohesive and homogenous vision of negro cultures,Footnote 11 the persistent search for the purity and authenticity of some of the practices with which they were associated, as expressed in attempts to have them designated as heritage elements, as well as in the insistence on seeing them as the polar opposite of the order being imposed at the time, reveals the social strength of this idea.

As a consequence of this belief in the existence of separate, irreconcilable cultural universes, Brazilian historiography on the First Republic gave rise to what Marc Hertzman defined as the ‘punishment paradigm’, according to which Afro-descended groups and their practices were said to have been constant targets of the Brazilian police during the early years of the Republic, subject to bans on the expression of customs and traditions of African origin in the nation's capital.Footnote 12 Given this alleged repression, many authors came to see negro cultural manifestations which would begin to be valued in the 1930s (such as samba and Carnival) as examples of the victorious ‘resistance’ of workers of African descent.Footnote 13

The experience of members of clubs such as Flor do Abacate, however, hints at a more complex situation. In posing proudly in 1911 for the photo – taken during one of their dances – they were promoting a process of cultural articulation that may best be understood in terms of the notion of cultural ‘connections’ proposed by the anthropologist Jean-Loup Amselle.Footnote 14 Moving away from belief in the unity and cohesion of cultures, he points to the essentialism at the root of concepts like mestiçagem/mestizaje, which operates through the idea of a mixture between two clearly definable cultures. Rather, he attempts to understand these processes of cultural articulation as fluid and dynamic, marked by the approximations and original creations of many subjects, working with the multiple references they were presented with. As Fredrik Barth suggests, instead of trying to ‘suppress the signs of incoherence and multiculturalism’ that characterise historical experience, in the attempt to grasp a ‘small, distinctive pattern’ of the culture of the Other, which might serve as a foundation for an evaluation of its endurance or transformation, one should move to understand it by way of the ‘“streams” of cultural traditions’ that effectively comprise its dynamic form.Footnote 15

It is from this dynamic concept of culture that we may return to Hertzman's critique of the ‘punishment paradigm’.Footnote 16 By demonstrating the fragility of the idea of a systematic repression of negro cultural practices throughout the First Republic, and showing how negro musicians themselves assisted in consolidating this myth as a way of affirming their authenticity, Hertzman helps to deconstruct the primary explanation for the affirmation of a mixed-race Brazilian culture starting in the 1930s. This interpretation had rested on the idea of a ‘discovery’, where intellectuals and men of letters were seen to adopt a positive view of an African-descended culture allegedly hitherto repressed.Footnote 17 Once the presumption of repression has been set aside, the task at hand must be to investigate the dynamics of the processes of turbulent communication which help explain the success obtained in the Rio de Janeiro of subsequent years by cultural manifestations associated with negros and pardos via another perspective, one that includes them as active subjects. This dynamic may only be understood by way of an analysis that sheds any essentialising of these cultural practices of negro origin so as to comprehend them through the processes that constitute them.

By presenting themselves as a group formed of people of African descent, but whose aim was to constitute a space of dance-focused, Carnivalesque sociability in keeping with the templates prized by the Carioca elites of the period, Flor do Abacate stands as a privileged object through which to expand on the reflection at hand. Though it was far from being the only alternative form of cultural expression sponsored by negros and pardos in the Rio de Janeiro of the period, the society gestured toward a form of articulation that would show itself to be very important in the Afro-descendant experience in Rio de Janeiro. With this in mind, we would do well to examine both the process that led to its creation and the challenges that it faced over the course of its development – so as to understand, from the perspective of its members, the logic that guided the constitution of their identities in Rio de Janeiro's Catete neighbourhood over the course of those years.

Negro Festivities in Transition

In organising themselves in a recreational organisation of their own in 1906, the founders of Flor do Abacate were stepping into the long history of the affirmation of festive practices of African descent in Brazil. Not limited to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, or even to Portuguese America, the process by which celebrations of African origin in the New World developed was shaped by the rhythm, flow and logic of the slave trade itself, starting in the sixteenth century. This was an Atlantic phenomenon, radiating from a variety of regions in Africa to the many places that made use of the forced labour of enslaved Africans.

Transcending national and city borders, the festivities organised by enslaved Africans and their descendants developed in a broad variety of directions wherever they emerged. In places like Havana and Buenos Aires, by the early nineteenth century there was already a visible effort in terms of an institutional recognition of their differences, reflected in the organisation of civil or religious societies that served as a space for the forging of bonds of mutual aid, as well as helping to organise dances and other celebrations.Footnote 18 In the Brazilian case, however, institutionalisation into independent associations was forbidden for those of African descent. Though many used religious brotherhoods as a way of expressing their identities,Footnote 19 and others turned to the communities around their professions to practise shared musical traditions,Footnote 20 throughout the 1860s and 1870s the Imperial Council of State systematically refused to grant permission for the institutional functioning of any civil association formed by those identifying as members of the ‘Congo Nation’ or as ‘men of colour’.Footnote 21 The logic was clear enough: by refusing to ‘speak of such things’, as one of the councillors put it, the imperial authorities were attempting to keep the control over the articulation of negro identities in the hands of the masters. As a consequence, informality and provisionality were the watchwords in the development of the so-called ‘batuques’ through the mid-nineteenth century. This term was the generic label that the lettered world used to describe negro festivities and celebrations enlivened by drums and dancing.Footnote 22

Though on the margins of institutionality, the development of such festive negro practices would, over time, lead to the affirmation of their legitimacy. Shaping themselves within the networks and logics of paternalistic control, and taking advantage of the permissive nature of Catholicism when it came to public festivities or lay brotherhoods formed by negros,Footnote 23 the celebrations organised by those of African descent staked out a measure of public recognition over the course of the second half of the nineteenth century which came close to transforming them into a newly minted right. This is what an episode recorded in 1866 in the parish of Santana, in downtown Rio de Janeiro, an area with a large population of negro workers, slave and free, would seem to suggest. On 24 June, the parish inspector wrote to the city's Câmara Municipal to report that the ‘batuques and toccatas of the blacks, having been prohibited by the Municipal Ordinances, have continued every Sunday’. Despite this, he said that he was unable to fine the offending parties, ‘as the officers’ complaint on this score is still awaiting the decision of the Illustrious Câmara’.Footnote 24

Just over a month later, the same inspector was back on the case. In a new report sent to the Câmara Municipal, he requested that the council members deliberate as to what ought to be his ‘behaviour regarding such gatherings’. He clarified that the urgency of the inquiry stemmed from the fact that, in the absence of any official decision, ‘such batuques have redoubled, inconveniencing the surroundings not a little’. At one such event he even spotted a ‘box for receiving the entry fees’, set out on the pavement. Worse still, when he went over with a few municipal guards, the revellers present showered them with ‘jeers’, ‘setting off rockets’ in their direction. Both the Câmara Municipal's delay in responding to the inspector's plea and the attendees’ brazen response to his approach left no doubt that the negros organising the festivities no longer worried in the slightest about hiding their activities from the authorities.

Nor should they have. When they finally heeded the inspector's request, the council members decided to send a message to the officer responsible for the neighbourhood, ‘requesting that steps be taken’. In his reply, the latter asked their leave to set out ‘some reflections’ on the matter, ‘so that justice may be served today and forevermore for those deserving of it’. In view of the inspector's complaint, he affirmed that he, as ‘the only legitimate local authority’, could not do away with the batuques in the area because ‘there [was] no doubt to be found in the law’ as to their legitimacy; the celebrations constituted a ‘time-honoured’ custom, one ‘always tolerated by all of the chiefs of police and their officers’. Though filtered through the paternalist prism of one placing himself above the negros participating in the batuques, the officer supported the celebrations continuing.

Even the public charging of entry fees, which was noted with horror by the complainant, struck the officer as nothing out of the ordinary, since ‘if merrymaking with entrance fees is a scandal, then theatres and public balls are long-standing scandals in their own right’. In comparing the batuques to other socially recognised and valued entertainments, he demonstrated his belief that those negro men and women had the right to their festivities. With this in mind, he was taken aback by the objections to the ‘continuation of the batuques’ specifically in his district, ‘when they were also held in the 2nd [district] on the same day’. The officer's words made it clear that these negro festivities were already socially accepted as a customary right, albeit one staked out within the tangled web of paternalism.Footnote 25

It should have come as no surprise, then, that the members of the Câmara Municipal, in adjudicating on the quarrel between the two authorities, wound up siding with the officer. Basing themselves on the idea that legislators would never ‘prohibit innocent diversions without good reason’, they declared the inspector's writs null and void.Footnote 26 In operating in the interstices of the seigneurial logic which treated such celebrations as a concession, slaves and free men of colour of Rio de Janeiro were able to guarantee an alternative form of leisure of their own. Even without an institutionalised space for their associations, as was the case in other countries, they managed to gain sufficient legitimacy to publicly expose their music- and dance-related practices. In doing so, they transformed their leisure activities into a right, one in which they showed themselves to be quite confident.

From the Streets to the Salons

Forty eventful years passed between the incident of the batuques in Santana and the foundation of Flor do Abacate. While consolidated at a point when pro-slavery policy dominated the political realm, the right of negros in Rio de Janeiro to celebrate as they wished was undermined by the many legal transformations related to their status between 1866 and 1906. As the product of the gradual deterioration of an ideology of seigneurial domination, which had begun to crumble with the law passed in September 1871 – the first step on the way to the effective end of slavery in 1888 and the proclamation of the Republic the following year – this and other customary rights would come to be cast aside in the name of implementing a political order bent on covering up the racial inequalities that marked Brazilian society.Footnote 27 Not unsurprisingly, the festivities characteristic of the African descent population in the nation's capital also shifted when put into dialogue with this new situation, in a process that helps to explain the formation of societies like Flor do Abacate.

Indeed, while negro festivities in the city were an issue left to the informality of custom through the mid-1880s, after the end of slavery and the implementation of a republican system they were subjected to stricter rules. The public authorities began to openly condemn and persecute batuques, which had once been seen as a private matter. By 1890, a few months after the regime change, the new Municipal Ordinances banned, ‘in drinking houses, taverns, and other public places, the gathering of people so as to give themselves over to toccatas, dances, and singing’. Another article prohibited, ‘in houses or country homes, the dancing-parties known as batuques, with drumming, singing, and dances’ – a ban that included the ‘Zé-Pereiras’, as the percussion groups that took to the streets during Carnival were known.Footnote 28 Though this failed to keep the batuques from continuing, as several complaints published in the press over the course of next few months attest, there followed a deliberate effort on the part of republican authorities to control negros’ right to promote their festivities, whether in the domestic sphere or in public areas.Footnote 29 Absent the legal distinctions which constructed social hierarchies, the celebrations organised by these groups were no longer looked at as a concession by the world of the senhores. Now they began to morph before the eyes of the powerful into a social hazard to be monitored and controlled.

In that context, however, control was not synonymous with prohibition. According to the first republican constitution in 1891, ‘to all it is licit to associate and assemble freely and without arms; the police cannot interfere except to maintain public order’,Footnote 30 and so it was within the legal structure created by the Republic that many African descent groups sought ways to affirm their leisure practices.Footnote 31 To ensure the legitimacy of their activities, the option they chose was to institutionalise their celebrations through the creation of recreational societies. To reinforce (and exert even more control over) this right, in September of 1893 the federal government passed a law regulating the organisation of associations of this type, determining that they might ‘acquire legal individuality’ by registering their statutes in the ‘civil registry for the district where they establish their headquarters’; other associations would be subject to the ‘rules regarding civil societies’.Footnote 32 While the policy had been to avoid the creation of negro societies throughout the Second Empire, now they were encouraged to institutionalise in order to facilitate the control and regulation of their practices. The creation of formal recreational associations became the best means to ensure the legitimacy of these negro and pardo revellers’ festivities, as police control over such events began to intensify.

During the late nineteenth century, this movement would also give rise to dancing societies like Prazer da Rosa Branca (Pleasure of the White Rose), in the Cidade Nova neighbourhood. Founded in December 1898, it had obtained a licence to operate by the following year.Footnote 33 To do so, its members had presented the chief of police with the names of a formally organised board of directors, in the style of the city's great recreational clubs. Here, however, the list included names like Germano Lopes da Silva, the club's mestre de salão,Footnote 34 a clerk,Footnote 35 and Armando do Espírito Santo, president of the club in 1902, who was a carpenter.Footnote 36 Since these were labourers, it was unsurprising that the club was not awash with resources, leading members to declare to the police that the association's headquarters was at 233 Rua General Pedra, the address of the vice-president himself.Footnote 37 Even so, by 1904 it had 40 members, making it one of the most popular of the 27 clubs and groups to be found in the neighbourhood.Footnote 38

While the social makeup of the club was similar to that of other small-scale dancing and Carnival associations established at the time, the ethnic unconventionality of its composition was noted by many a writer. In a crônica, or short newspaper piece, published in 1906, João do Rio described being struck as he heard, ‘as if rising to the heavens, the frenetic sound of the bombos [bass drums], drums, and atabaques [conga drums]’ of a group heading in his direction. ‘It was Rosa Branca, spangling negros draped in silks, from the Rua dos Cajueiros’,Footnote 39 he explained, alluding to the society's new address.

João do Rio had taken it upon himself to draw up a painstaking description of Rosa Branca's activities in another crônica published in during the previous year's Carnival – in which he wrote that he had been sought out by ‘a feiticeiro [wizard or witch doctor] named Bemzinho’, an old acquaintance, who was looking for ‘a licence’ for the club.Footnote 40 This provided an occasion for the narrator to visit Rosa Branca, which on that day would be host to a Carnival rehearsal with ‘a soiree and samba in the back room’. Venturing through the association's modest accommodation, he heard dancing and singing ‘to the sound of pandeiros [tambourines] and atabaques’. He was visibly impressed by the administrative organisation of the club, whose numerous directors ensured that the festivities went as planned. ‘These important posts are almost always occupied by those who aid in feitiçaria [witchcraft]’, one member commented, speaking to the close proximity between religious and festive practices among these workers of African descent. Although in daily practice the club's dancing-related activities mingled with those of a Carnivalesque or religious character, João do Rio's source explained that a ‘licence is always requested for a dancing society’. This attested to the importance of this sort of document for these societies, which used it to obtain the legitimacy necessary to develop their recreational practices.

The club thus presented itself as a privileged space for the expression of customs and practices to which its own members attributed a strong African origin, albeit crossed with other musical and dance influences – as João do Rio also would note. For the cronista (chronicler), trying to describe an environment whose logic tended to escape him, this was a simple strategy to affirm the legitimacy of the club's celebrations. ‘Whoever wants to samba heads to the back, and those more given to ballroom dancing keep on polkaing up front’, he explained. For him, the difference between the two spaces was very clear: while the area further back expressed a musicality with its ‘origin[s] in the dances of the backlands of Central Africa’, dances up front were ‘much gentler’ – ‘one dances slowly, to the sound of a flute and a cavaquinho [small guitar]’ – and set to rhythms that, though African in their syncopations, were already accepted in much more refined environments, given the fact that they reconciled musical forms of European origin with rhythmic practices often associated with Africa. João do Rio's pen thus gave shape to an essentialist image of these dances, one often reaffirmed by the historiography, which repeatedly wielded this image of the different spaces within a single festivity to suggest the need to hide or disguise the musical influences of African origin which made their presence felt.Footnote 41

From the point of view of the members of clubs like Rosa Branca, however, there seemed nothing strange about the fact that a variety of musical forms was present in their dances. Though the orchestras and bands providing musical backing for the festivities tended to set up shop in the main hall, which was generally larger and faced the street, the fact that these various rhythms, sambas and polkas, for example, appeared at the same event suggests, on the contrary, that they were seen in the same light by those enjoying themselves throughout the various spaces set up by the society. This evident continuity moves against both the essentialist perspective by which the author of the crônica describes the batuques in the back of the club's headquarters, as well as the prim image that he presents of the music played up front. The ‘negros and mulattoes’ described by João do Rio evidently found in Rosa Branca a recreational space of their own, where they might engage in the multiple musical and dance genres that sparked their interest at the time. It was thus hardly surprising that dozens of similarly structured associations should emerge around the same time, providing a wide array of places where the city's negro and pardo residents might enjoy themselves – such as the Sociedade Dançante e Carnavalesco União das Flores (Flower Union Dancing and Carnival Society), whose headquarters was on the same street as Rosa Branca, or the Club Carnavalesco Flor da China (China Flower Carnival Club), whose 1906 secretary was recorded as the president of Rosa Branca the year before.Footnote 42

The founding of Flor do Abacate must be understood as a part of this process. With an orchestra of its own by 1907 – as one advertisement for the society emphasisedFootnote 43 – Flor do Abacate would promote a syncopated musicality which was at the heart of its dances and parades. With cavaquinhos, flutes, guitars and pandeiros, its members played ‘the most beautiful chulas’Footnote 44 and hosted ‘quite lively sambas and batuques’, whether in small gatherings and outings around the city or in full-blown dances that lasted ‘till nearly dawn’.Footnote 45 On other occasions, they would take advantage of the structure established by the society to engage in practices which were by then common to many groups of African descent in the city, such as the organisation of festive feijoadas and visits to the Festa da Penha.Footnote 46 As a result, their festivities bore the mark of negro culture that they recognised to be similar to that of other recreational associations of the period, with which they tended to fraternise.Footnote 47

In coming together to create Flor do Abacate, the negro and pardo men and women from the Catete area were seeking to construct a space of self-expression and amusement in which they might engage in their own leisure activities. In dialogue with current legal ordinances, they adapted to the new, republican times in an attempt to ensure the continuity of an independence they had staked out over previous decades in a number of different ways. Though within the limited scope provided by a private club, they gave shape to a recreational space in which they tried to keep on enjoying themselves in their own way.

Legitimacy under Construction

By then, however, the members of Flor do Abacate must have been aware of the limits of the stability they sought by institutionalising their group. No matter how they tried to adapt to the republican order, these small societies faced a series of checks and obstacles which littered their path to legitimacy. Subjected to control by the police, they had to renew their licences every year via a request sent to the chief of police of Rio de Janeiro, along with the statutes of the club. But just as Flor do Abacate was founded, these norms were about to be tightened by way of a 1907 federal decree regarding establishments of public entertainment in the city. The new rule stipulated that ‘clubs, recreational societies and other similar establishments’ were to undergo inspections by the police if they were to continue operating regularly. The decree also stated that the chief of police might ‘temporarily or definitively prohibit’ the operation of any ‘club or recreational society that may infringe on the provisions of this regulation, or when judged convenient, for the good of public order, security and morality’.Footnote 48 Conformity with norms defined by the authorities in order to institutionalise the functioning of these organisations thus represented the first step in the process of constructing a perennially tenuous legitimacy, one that would have to be reaffirmed, daily and on an ever-clearer basis, over the course of years to come.

This is what the members of the club in Catete must have understood, shortly after the founding of the society, when the chief of police decided to revoke their newly issued licence. The first alleged reason was an incident at a dance hosted by the club on 22 December 1907. According to reports in the press, things ‘were going gaily’ throughout its halls, which ‘overflowed with dozens of couples’ engaged in lively dancing. Suddenly, the papers reported, that gaiety was interrupted by the entrance of one Arthur Mulatinho – an individual characterised as a ‘dangerous ruffian’ in police reports published in previous years, and who had already taken part in serious clashes at other Carnival societies.Footnote 49 With a defiant air, he apparently ordered that the music stop so that he might show off in the middle of the hall, whether by dancing ‘a polka’ with his umbrella or whirling around with a lady he forced to be his partner. In the face of such behaviour, Flor do Abacate's mestre-sala tried to ‘call [the invader] to order’. By way of a reply, the latter pulled out a revolver and shot at him twice. When both shots missed, he leaped on the man, starting a fight that would be broken up only by the arrival of the district police. As a result, the next day's papers announced that the club had been stripped of its licence.Footnote 50

In shutting down the society in response to the brawl, the police showed that they saw it as the sort of suspect place that might favour such behaviour. Even so, the physical violence allegedly fostered by the club's environment does not seem to have been the only motive driving police repression. Another crime at the same dance would serve to justify the crackdown: the rape of Julia de Oliveira e Silva, a minor.Footnote 51 As she stated to the police, she had gone out to dance that night at Flor do Abacate, and was then ‘seduced and raped by her beau, Antonio Martins de Castro’ in an area at the back of the club's headquarters. He, for his part, declared that he had known her for over a year, ‘but that he had never dated her’. Though he admitted to having gone to the dance ‘in Julia's company, with whom [he then] danced’, he denied the rape. His arguments would ultimately convince the judge, who wound up declaring him innocent. Beyond the personal drama, the case sheds light on another suspicion aimed at clubs like this: that they were immoral spaces, ripe for such sexual offences.

One last accusation would ultimately bolster the chief of police's decision to keep the club from operating: the suspicion that illegal games of chance were being played there. On the same day that other papers reported on the scuffle at the club, O Século published an article announcing that Flor do Abacate's licence had been withdrawn because of allegations that ‘prohibited games were played there’.Footnote 52 This drew a connection between the club and the search for easy money by way of gambling, a posture characteristic of vagrancy (vadiagem). A practice criminalised in the first penal code established by the Republic, at a point in time at which the fluid nature of the job market made it difficult for a worker to provide evidence of a steady occupation, this norm cast a permanent cloud of suspicion over the lives of men and women such as those who frequented Flor do Abacate.Footnote 53 By tarring the very headquarters of their society with the same brush, the police were attempting to paint its activities as suspect, thus justifying permanent surveillance of the place.

Violence, immorality and vagrancy were the charges that the members of Flor do Abacate were forced to fight in an attempt to legitimise and consolidate their recreational space. This trio was hardly coincidental; all three accusations were linked, directly or indirectly, to suspicions fed by the strain of racial thought dominant among sectors of lettered Brazilian society ever since the decline of the paternalistic stance linked to seigneurial ideology. Represented in exemplary fashion by the writings of Bahian doctor Raymundo Nina Rodrigues, who published an 1894 work detailing changes he believed necessary in the republican penal code, these theories held that negros and pardos bore the ills of their racial makeup in their very nature, and that they could not be subject to the same laws as whites.Footnote 54 Turning to other racist authors, Rodrigues argued that negros had ‘incomplete cerebration’, giving them an ‘unstable, childlike character’ marked by ‘impulsiveness’, a sign of the ‘brutal instincts of the African’, making negros ‘hot-tempered, violent in [their] sexual impulses, [and] with a strong inclination towards drunkenness’. Mestizo individuals, meanwhile, were cast as suffering from the degenerative effects of this intermingling of types – a process that, to Rodrigues’ eye, could only result in ‘evidently abnormal products’. This degeneration, he wrote, manifested itself in an ‘impulsiveness’ that he linked to violence, an ‘indolence’ that made them incapable of working, and an exaggerated sensuality that might ‘nearly reach the limits of sexual perversion’, this last evil represented perfectly by the figure of the mulatta, or mestizo woman.Footnote 55 From this point of view, negros and pardos were naturally given to the deviant behaviours that had warranted the closing of the club in 1907; they were the ‘dangerous classes’ that police were tasked to keep under surveillance.Footnote 56 It was thus no surprise that suspicions such as these should come to hang over many recreational societies whose membership was similar to that of Flor do Abacate.

As a result, in addition to having to constantly shore up the society's institutional legality, the members of the club were now forced to stake out a measure of legitimacy for their organisation on a daily basis, even as it came under fire from the press and authorities alike. That was what they were trying to do as they worked to put forth an image of themselves as law-abiding workers, a common strategy for those looking to evade police control.Footnote 57 In the report that he sent to the chief of police on 30 December of that year, requesting that he reconsider his decision to annul the licence, José Roberto Monteiro, the club's president, demonstrated a keen familiarity with the boxes he should be ticking in order to be seen as acceptable. Having claimed that ‘the society's members are all law-abiding, working men’, he declared that Arthur Mulatinho, the instigator in the fight, was not one of them. He also argued that the fight broke out ‘not in the social hall, but in the corridor where the individual in question had attempted to enter’ – since, as he put it, within the club itself ‘order was always maintained’.Footnote 58 The president's appeal thus reproduced a view of the danger associated with men like Arthur Mulatinho in an attempt to lend Flor do Abacate a respectable air.

At first, the strategy seemed to have no effect. In response to the report, the section chief of the 6th Police District stated yet again that the fight had taken place ‘in one of the halls of the society's headquarters’, while Alvaro Vasconcellos, his first deputy, chimed in by saying that the club tended to receive ‘known ruffians’.Footnote 59 With this in mind, the chief of police rejected the request for reconsideration from the directors of Flor do Abacate on 8 January 1908: this shows how the lines separating the alleged vagrant from the law-abiding worker were not objectively determined, and instead gave rise to a complex field of disputes and negotiations.Footnote 60

Shortly over a month later, however, the club would once again appear on the list of societies with licences to operate during that year's Carnival.Footnote 61 The attention paid by its directors to the criteria which had led to the rejection of the appeal, in a push begun before the incident, seem to have borne fruit. A few months earlier, in March 1907, in an advertisement in the popular newspaper Jornal do Brasil to publicise one of the club's dances, the society's board clarified that they would be putting ‘a group at the door to block the entry of gentlemen and ladies who may be judged unbecoming, and another group in the hall to invite those people who behave poorly in said space to make their exit’.Footnote 62 The fight at the club in December of the same year, sparked by the mestre-sala’s attempt to remove a disorderly individual, evinces the care that club officers had taken to enforce this rule, although it was never made part of the statutes – yet more evidence of the effort to affirm the law-abiding, disciplined nature of the society.

In the case of Flor do Abacate, the successful drive to cement the club's distinction amidst a social milieu seen as dangerous was bolstered by the fact that its festivities and parades fell into styles of celebration that could be easily recognised by the lettered world. Rather than presenting them as a direct continuation of the old batuques that their parents and grandparents might have taken part in decades earlier, the club's members repeatedly affirmed the sophistication of the society, as expressed in the adoption of recreational practices and forms of amusement that were anything but traditional. At first, this came through in the musical forms that they adopted, a far cry from the style described by those who witnessed negro festivities in the nineteenth century. Though the syncopation often tied to African musicality was a crucial identity-related element of the events organised by the club's members, it did not stand as a defining characteristic, since syncopated rhythms had spread throughout the Brazilian music world by the early twentieth century.Footnote 63 This meant that dances at the club were set to rhythms, instruments and dance styles quite similar to those to be found in the city's most elegant salons – such as the ‘cançonetas’ sung by one member at a 1908 event, the ‘English quadrilles’ that the directors promised would be played at midnight during a 1909 dance, or the waltzes to which a writer at A Época saw many couples twirling throughout Flor do Abacate's halls.Footnote 64

Beyond matters of rhythm, this sophistication was also manifest in the lyrics of the songs intoned during dances and parades by the members of Flor do Abacate. At a point at which Brazilian poetic production was marked by an aesthetic that valued cosmopolitanism and form over content, resulting in polished verses worlds apart from both the habitual forms of expression of contemporaries and the issues that shaped their lives,Footnote 65 a similar attempt at elevation was discernible in many of the lyrics composed by the club's members. The march ‘A tarde amena’ (The Mild Afternoon), which Flor do Abacate would sing along the streets during Carnival in 1913, hailed the ‘white herons’ which, ‘fluttering their wings’ in search of the ‘blue of the azure sky’, made the singers forget about ‘altogether impertinent’ passions; another song that the club took to the streets in the same year, meanwhile, sang of the ‘dulcet nightingale’, with its ‘sorrowing, contented warbling’.Footnote 66 Having distanced themselves from the African-influenced expression of the jongos still sung by many former slaves and their descendants in the Paraíba Valley region,Footnote 67 these early twentieth-century revellers in Rio de Janeiro presented themselves to society with lyrics in tune with the literary consensus of the time.

Finally, this sophistication was evident in the dances and other events held by Flor de Abacate and societies like it. Shunning the accessories that the lettered world associated with negro festivities, such as the feathers and live animals taken to the streets during Carnivals past by Cucumbi groups,Footnote 68 these new groups adopted an aesthetic not unlike that to be found in associations frequented by Rio's elite, although with far fewer resources than the latter. According to one crônica at the newspaper O Paiz, during the dances held by the Flor do Abacate its halls were ‘richly decorated in natural flowers and the other ornaments that good taste demands’.Footnote 69 Another report published in the same paper two weeks earlier had stated that members tended to perform in their parades ‘with great gusto’, given the ‘luxurious trappings’ that they prepared with ‘flawless care’.Footnote 70 Though the article refrained from describing what, exactly, that good taste and flawless care consisted of, the adjectives – as well as the somewhat condescending tone with which they were used by writers accustomed to the sumptuous wealth of the great Carnival societies – showed that this was a way of recognising in Flor do Abacate the same aesthetic principles as those that were upheld in more well-to-do associations. As a result, just a few years after having lost its licence, the club was being characterised in the press by the ‘distinction and refinement’ with which its members generally performed.Footnote 71

In a club made up of low-income workers, however, this sort of revelry racked up costs that constantly threatened its ability to function. In addition to ensuring that everything was up to standard with public authorities, the directors of the association also needed to make their activities financially viable. At times they were able to rely on help from better-off sympathisers, such as the students who held a ‘literary fête’ at the club's headquarters in 1909 to benefit the club's coffers.Footnote 72 Most of the time, however, these associations survived on monthly fees paid by their members, ranging from 1,000 to 3,000 réis – a value roughly equivalent to the cost of a monthly newspaper subscription. This gave Flor do Abacate a monthly income of around 80,000 réis – not enough even to pay the rent on the space where it was headquartered in 1912, which stood at 90,000 réis. It is hardly surprising, then, that, in that same year, the Sociedade Musical Prazer da Glória (Pleasure of Glory Music Society), which was subletting a part of its headquarters to the club, sued it for four months’ unpaid rent.Footnote 73 The year before, the club had also been targeted by a suit seeking to collect 250,000 réis, left unpaid from a debt of 600,000 réis to a neighbourhood businessman, ‘deriving from orders of costume shoes for Carnival’.Footnote 74

To keep up the standard that had won them a measure of distinction, the club's managers often turned to a variety of expedients aimed at padding out their revenue. This was mainly done informally, by way of the admittance of ‘guests’ at the dances, sidestepping police restrictions on paying to gain entry to such events. By paying a month's worth of fees when they came in, they supplemented the club's income under the pretence of being old members who had not subscribed yet – though this tack would give rise to problems like the December 1907 fight instigated by Arthur Mulatinho. In an attempt to make their events even more interesting and lucrative, club officers at times prominently advertised that there would be a tômbola – that is, that they would include bingos and raffles – potentially attracting police suspicion of illegal gambling.Footnote 75 In addition to entertaining members, the dances served the explicit role of ‘benefiting the society's coffers’, making its activities possible.Footnote 76 At the same time, however, they also laid bare the fragility of the moral standards upheld by the club officials in the attempt to garner legitimacy; in allowing paid entry tickets and games of chance, the society, from an institutional perspective, only confirmed the police's suspicions about it.

The success of this strategy thus hung on publicising its celebrations and the positive image constructed around them. Good relations with the press, which covered the club's activities, were key in this sense. At a time when the city's major newspapers were clearly opening up to the tastes of a wider audience, making room for everyday topics of interest to potential readers – such as football, crime and the dances themselvesFootnote 77 – they became privileged media by which to spread the word about goings-on at these clubs.

It should come as no surprise that, after the episode that resulted in the cancellation of its licence, subsequent administrations at Flor do Abacate strove to forge cordial relations with Rio's largest press outlets. During a 1910 New Year's procession, members made a point of visiting the newsrooms of the city's most important newspapers with their ‘finely tuned guitars and cavaquinhos’, where they were met with praise and ‘gratitude’.Footnote 78 In March of the same year, they held a ball in honour of the press, which was described in the advertisement as an ‘ideal daughter of Gutenberg, spurring us on to artistic battles, where we have been able to gather the long-desired laurels of victory’.Footnote 79 Having been received as guests of honour in the halls of the association, Carnival writers at Rio's major newspapers became permanent allies in the club's cause.Footnote 80

Thus emerged a pattern by which the members of Flor do Abacate might stake out the legitimacy of and ensure support for their festivities. Thanks to this model, the society would be able to renew its licence without much difficulty for years to come, despite other occasional conflicts at its headquarters.Footnote 81 ‘I can find nothing to discredit the conduct of the administration of the Sociedade Flor do Abacate’, a police commissioner wrote to a district police chief when questioned in 1913 as to the concession of its licence; the following year, another commissioner would respond to the same question by affirming that the club's officers were ‘upstanding people’.Footnote 82 At a time in which racial thinking continued to feed perspectives and prejudices that cast negros and pardos as potential suspects, the club's members managed to set aside a space where they might enjoy themselves at their own dances and processions, legitimised by their own hands.

Negro, Brazilian and Modern

Beyond securing a legitimate space in which to engage in their recreation, the process by which societies like Flor do Abacate came to be consolidated sprang from its members’ struggle to underscore its Brazilianness and modernity. In setting themselves apart from the practices traditionally associated with the world of negro culture, such as batuques, the members of these clubs forged a space in which they might express another sort of identity, one which they defined as markedly cosmopolitan. Far from falling into a strategic effort to accept cultural forms imposed on them, the choices they made spoke to the intensity of the dialogue and the exchanges they kept up with other cultural influences and networks, helping to constantly reinvigorate and reshape their own festivities. Alongside the affirmation of a recreational space of their own for workers of African descent (favoured targets of police surveillance), there emerged new musical and dance practices in dialogue with the production and tastes of various other social groups, in a process by which these individuals asserted their place as a constituent part of the nation that was attempting to exclude them.

Not that this was an easy task. The sorts of celebrations that they organised, strongly linked to negro and pardo workers, were often mocked in the mainstream papers by cronistas and cartoonists who seemed not to understand their meaning.Footnote 83 In the face of this, the members of Flor do Abacate tried to make their society into a means by which to cast themselves as part of the same movement that gave rise to better-off celebrations. They hoped to distance themselves from the negative image frequently associated with negros and pardos, looking to construct a modern one in its place; this, in turn, would be returned to in decades to come by negro musicians and militants, who adopted a similar strategy in hopes of escaping from the stereotypes with which they were often tarred.Footnote 84

This inclusive aspect of the form that Flor do Abacate took on is evident in the very name chosen for the association. In selecting as their emblem the flower of a fruit with the same colours as the Brazilian flag – which also adorned the society's flags and standards – members were signalling that they were a part of the nation's identity, then still under construction. Their line of reasoning in doing so may be gleaned from the lyrics sung by the group in 1908 during Carnival, which they made a point of sending to the Gazeta de Notícias:

In describing Flor do Abacate as ‘elegant and beautiful’, the members of the society were attempting to make their ‘dream of strength’ come true. As part of that effort, they insisted on affirming a strong sense of national identity, as expressed in the link drawn in the final verses between the club and the colours of the Brazilian flag. This explained its name, referring to the flower of a fruit whose yellow and green hues recalled those of the nation. Similarly, this seemed to shed light on why members insisted on holding festive dances to celebrate the most important civic holidays of the age, such as Independence Day and the date of the Proclamation of the Republic.Footnote 86 This affirmation, that they were a part of this nation that often did its best to shut them out, helps to explain the form that Flor do Abacate took on at its inception.

The peculiarities of the way in which they expressed this sense of nationality, however, are brought out in the fact that their grandiloquent verses, whether in the street or in the dance hall, were set to rhythms described by the newspapers as ‘chulas’ or ‘samba’.Footnote 87 While João do Rio's 1904 account was marked by the perspective of a lettered narrator attempting to classify and order the various rhythms present there, leading him to draw a distinction between the ‘polkas’ played in the front room and the ‘sambas’ supposedly confined to the back, in the festivities at Flor do Abacate these different musical forms were clearly mixed together, forming the hallmark of the society's dances and processions. At each event, the press and the club's administration made fresh mention of the ‘maxixes’, or even ‘chulas, marches, and tangos’, as the secretary put it in one advertisement, which would liven up the society's halls.Footnote 88 In order to do justice to this musical diversity, the very makeup of the musical groups playing at the club was unique. While the city's most elegant balls were accompanied by large wind ensembles, the musical backing for the parties organised by Flor do Abacate were far more modest, as suggested by the description of the ‘orchestra of guitars, cavaquinhos, clarinets, and brass’ present at one society dance in 1910. These strategic decisions emphasised and favoured the development of both harmony and rhythm.Footnote 89 Though they adopted musical and dance styles similar to those of Rio's most well-heeled organisations, the negro and pardo workers in clubs like Flor do Abacate did so in keeping with their own interests and tastes, drawing on chic fads as well as customs shared in their own families.

The peculiar result of this blend was quite visible to contemporaries, as may be suggested by the juxtaposition of two 1905 drawings, which were displayed side by side in an exhibition curated by cartoonist Calixto Cordeiro in 1911.Footnote 90 The first, ‘O Baile Rico’ (or ‘The Rich Ball’), looked to portray one of the elegant salons where Rio's elites gave themselves over to the pleasures of dancing (Figure 2).

Figure 2. O Baile Rico (‘The Rich Ball’)

The image leaves no doubt as to the elegance and distinction of the event, reinforced by the white skin and delicate features of the couples on the dance floor. Dressed in dinner suits and fine gowns, the guests dance primly, their movements evocative of waltzes or other European genres. The ample, richly adorned hall presents a refined backdrop with a large orchestra which, to judge from the position of the dancers’ legs, was playing pieces more focused on harmony than on rhythm, that might be heard in any elegant dance hall in Brazil or Europe.

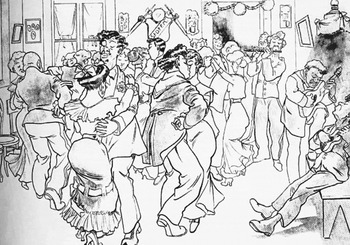

Calixto's depiction of another sort of dance, meanwhile, was very different. The sort of event hosted at clubs like Flor do Abacate was represented in another of his illustrations, this one entitled ‘O Baile Pobre’ (or ‘The Poor Ball’) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. O Baile Pobre (‘The Poor Ball’)

This illustration, placed next to Figure 2 at Calixto's exhibition, is clearly closely related to it. Both depict a dance where those present have paired off into couples. The second cartoon, however, makes it perfectly clear just how different the two spaces are. From the initials on the shield hanging on the wall, one can make out that this was a Sociedade Familiar Dançante (Family Dancing Society), just like Flor do Abacate. In a modest hall much smaller than the one in the previous illustration, men and women, evidently negro and mestizo, enjoy themselves responsibly in a homely atmosphere. The musical backing here is comprised of just a cavaquinho, a guitar, and a flute. The small group is not set apart on a stage or in a different room, but rather mingles with the dancing couples, in a setup reflective of many such simple dances in the Rio de Janeiro of the time.

In bringing out the similarities and differences between the two images, Calixto bore witness to the explicitly social and ethnic distinctions that shaped the dances and festivities organised by these small associations. Portrayed with an ironic air, as if to suggest the difficulty that those in these small clubs faced in attempting to match up to the standards of a recreational activity of greater refinement, the societies are set apart principally by the fact of being frequented by workers of African descent. The dances held at clubs like Flor do Abacate, in the eyes of much of the lettered world, were perceived as the specific cultural manifestations of these workers.

In this image, however, Calixto would ultimately underscore characteristics of these dances that went beyond the fact of the participants’ race. In his depiction of the couples engaged in their ‘choro’,Footnote 91 he drew the dancers with their knees slightly bent and their legs entwined with their partner's, as if to indicate that they were dancing to a different rhythm from the dandies in the previous image – one more heavily marked by syncopation. This representation ties the illustration to the sort of dance criticised in May of 1905 in a crônica published in the newspaper A Notícia. ‘The salons of today have utterly lost any tradition of elegance’, the writer complained, lamenting the gradual disappearance of the ‘elegant, delightful dances of yesteryear’, with their ‘measured combinations set to gentle rhythms, in which sedate, solemn steps alternated with drawn-out bows and curtsies’. In place of these genres, clubs like Flor do Abacate were adopting a sort of ‘modern dance’ which, in the author's opinion, was only good for ‘making one sweat’. ‘Today, the art of the dance has degenerated into a barbarous system of brutal galloping and graceless twirls, losing all its character’, the complaint went on, asserting that these new rhythms were better suited for ‘courtship and lascivious contact’ than ‘to serve the artistic intention of a visual exercise’. These rhythms were duly dubbed a ‘dance for monkeys or epileptics, leaps befitting the possessed, hip-shaking befitting those not in their right minds’, laying out the clear distinction that the author believed to exist between the sorts of dances portrayed in the two images: ‘the modern [style] is all brutality and fatigue; the old [style] was all grace and repose’.Footnote 92

Though they deliberately took part in certain festive, music- and dance-related elements which had not been a part of the celebrations organised by their grandparents, and which were to be seen in the more refined clubs in the nation's capital (such as the hosting of private dances, the introduction of musical harmony, and the practice of pairing off to dance), these small societies gave them a form of their own, tied to their own taste for a syncopated form of music that they were quite familiar with. It was hardly surprising, in that sense, that these clubs should have also become spaces ripe for the articulation of the social and racial identities that characterised their members. In constituting an effective means of organisation for workers from different areas,Footnote 93 the members of these clubs were taking part in a process that went beyond the dancing clubs themselves, and which often blurred the boundaries between recreational and campaigning forms of associative life.Footnote 94 The fact that activities sponsored by these clubs tied into the tastes, habits and reasoning of the many workers who enjoyed themselves there seemed to explain the ferocity of the strongly racialised opinions expressed in the crônica.

Testimonies such as these speak to the intentional modernity of the sort of cultural framework forged by the members of Flor do Abacate. At a time when thinkers such as Luiz de Castro recognised that ‘dances of slow movement[s]’ had ‘fallen into disuse’, it was in these small dance halls that ‘modern dance’, with its ‘quick movements’, would express itself with full force.Footnote 95 Those belonging to small clubs such as the one in question thus promoted a musical style that, in spite of being strongly syncopated (or perhaps precisely because of it), was also both new and cosmopolitan, to the despair of lettered intellectuals given to tradition and distinction.Footnote 96 In doing so, they placed themselves in the vanguard of the process that would shape musical and dance genres recognised globally as ‘modern’, playing an active part in a movement that was just beginning to spread throughout the Atlantic world.

The meaning behind the nationalistic frenzy of Flor do Abacate's members may be understood more clearly from this angle. While casting themselves as constituent parts of a cosmopolitan trend in the process of fitting itself into Brazilian culture, they did so without failing to emphasise their distinctiveness, an identity tied to social and racial origins that were quite visible to their contemporaries. Theirs was an inclusive posture, presenting them as active subjects in the republican nation in the making. It was by playing up such connections that the members of the association were able to construct the legitimacy of their social space through a variety of influences and dynamics.

Within the process of shaping a simultaneously Brazilian and modern identity for themselves, the members of Flor do Abacate and other recreational workers’ societies would help to construct new images of dance and Carnival clubs of the same kind. With each new event, the ‘tireless twosomes’ enjoying themselves there danced enthusiastically till dawn found them in ‘absolute harmony’, rocked by a musical style that one cronista would define, years later, as ‘leg-shattering’.Footnote 97 It was hardly surprising that their dances drew considerable crowds, as evidenced by the ‘mass of people’ thronging outside its headquarters during one of the parties organised by the club in 1911.Footnote 98 Able to drive the ‘people of Rio’ to ‘immense delirium’, Flor do Abacate was defined that year by a cronista at the newspaper A Imprensa as a ‘popular and well-loved society’, while another referred to it as a ‘beloved, madly popular’ association.Footnote 99 Not coincidentally, just over three years after its establishment, the society found that it needed to move to a larger site, faced with the need to host its dances in quarters befitting its ‘large number of members’.Footnote 100

In addition to inspiring the city's working classes, Flor do Abacate slowly began to garner recognition and visibility amongst sectors of the lettered world. While groups like these would remain targets of police surveillance for years to come, it became common for cronistas and journalists at several newspapers to comment on the ‘original fashion’ in which these clubs were organised, the ‘extremely original dances’ to be seen there, or the ‘unexplainable’ music they played.Footnote 101 ‘That's what you call people who know how to play around, entertaining themselves and others’, a cronista at Correio da Manhã wrote, in reference to Flor do Abacate.Footnote 102 ‘This is what appears before our eyes, and it is this that gradually makes its way into our hearts’, a writer at A Imprensa would chime in, also in reference to the society.Footnote 103

Formed of a member base that many of those writing in the city's papers would come to recognise as ‘honest, hard-working, tireless people’, a ‘law-abiding, upstanding working class’, by 1911 Flor do Abacate would be seen as ‘the most well-rounded of the small societies’, the ‘lodestar for her sisters’.Footnote 104 Alongside other associations undergoing a similar process, the club thus helped to define a standard that would later be adopted by many other societies, even more well-established ones. It was no mere chance that in 1913 Flor do Abacate (alongside the Ameno Resedá [Pleasant Crepe Myrtle] and Recreio das Flores [Pleasure of Flowers] dance associations) would receive requests from producers of light theatre to participate in a ‘grandiose triumphal entrance’ at their shows.Footnote 105 By the following year, Álvaro Sandim, one of the society's members, would compose the polka ‘Flor do Abacate’, the rhythm and melody of which attempted to capture the musicality often to be heard at the club.Footnote 106 The association thus helped to consolidate a new model for dancing clubs attended by workers, where the affirmation of a sense of nation and modernity went alongside the recognition of the social and ethnic distinctiveness of the group's members.

It was by way of daily demonstrations of the strength of this original framework, the result of their promoting dynamic cultural connections in which they were active subjects, that the many men and women who enjoyed themselves at clubs such as Flor do Abacate would come to stake out an effective medium of social affirmation. As they underscored the power and legitimacy of their tastes, practices and customs, they also attempted to redefine them in dialogue with other veins of cultural tradition, casting off any shadow of essentialism or primitivism. In doing so, they signalled the modern meaning of practices and customs that would be valued by modernist intellectuals only in the 1930s, as part of an attempt to affirm that which Hermano Vianna defined as ‘a new model of national authenticity’.Footnote 107 Far from the passive role to which they were so often relegated, both by those intellectuals and later historians, they took an active part in the construction of a mestizo, modern image for Brazilian culture.