Introduction

In May 1973, urban Brazilians were confronted by a series of advertisements on billboards posted throughout many cities and in the most prominent daily newspapers. Planned by Finance Minister Antônio Delfim Netto and Brazil's leading advertising professionals and carried out by the civil–military dictatorship led by General Emílio Garrastazu Médici, the ads formed part of a new campaign to fight the growing problem of inflation. Instead of the traditional economic levers of fiscal, monetary and price policies to address inflation, Delfim Netto turned to advertising.Footnote 1 The campaign sought to teach urban women to shop at different stores as a way to prevent shopkeepers from charging high prices, which, in theory, would lower prices in the aggregate.Footnote 2 Reproduced in Image 1, an ad targeting women features the tagline ‘But you paid all that, dear?’ above an image of two young white women wearing the same dress. Addressing women directly, the copy describes a situation in which ‘you bought a dress that is lovely but when you arrive at the party, your worst friend is there with a dress identical in everything but the price’. The text then shifts to the command, ‘Compare prices’, telling women that ‘Money, a little or a lot, is in your hands.’ It concludes: ‘Always spend it wisely. That's exactly what the government wants. That's all your husband asks.’ Inflation would be controlled in Brazil, implies the ad, if only women would do as the government ‘wants’ and their husbands ‘ask’.

Image 1. Advertisement: ‘But you paid all that, dear?’

Source: Jornal do Brasil, 20 May 1973, Caderno B, p. 15.

The 1973 advertising campaign appeared amidst economic and social troubles for the Médici regime. Beginning around 1968, Delfim Netto helped spark several years of significant economic and industrial growth with relatively low and stable inflation, a period known as the ‘Brazilian economic miracle’.Footnote 3 Yet by early 1972 there were signs that the same policies that propelled economic growth were also causing renewed inflation. The Médici regime required high rates of economic growth and low inflation to secure social legitimacy to ward off calls for democracy. Unable to attack inflation with economic policies because those policies would stunt growth, Delfim, working with advertising professionals, decided to fight inflation with an advertising campaign. His successor as finance minister, Mário Henrique Simonsen, faced a similar predicament in 1977, and he too turned to advertising.

This article examines the Brazilian civil–military dictatorship's two anti-inflation advertising campaigns:Footnote 4 1973's ‘Say No to Inflation’ (Diga não à inflação) and 1977's ‘People's Current against Inflation’ (Corrente do povo contra a inflação), popularly mocked as the ‘Bargaining Campaign’ (Campanha da pechincha). Though scholars have analysed the military regime's use of advertising, or ‘propaganda’, as a main policy lever,Footnote 5 the two anti-inflation advertising campaigns have largely gone unnoticed.Footnote 6 Describing the two campaigns in relation to the economic, political and social contexts in which they appeared, this article argues that Delfim Netto and Simonsen turned to advertising to divert attention from their own policy failures by blaming urban women, small shopkeepers and consumers for the growing inflation problem. It also illustrates how advertising served as a substitute for economic policy-making. The economics literature about Brazil in the 1970s does not mention these campaigns even though officials portrayed them as key parts of their overall set of policies to achieve the economic goal of reducing inflation.Footnote 7

The two anti-inflation advertising campaigns are also fruitful topics for gender analysis. Though there are large literatures about gender during the civil–military dictatorship (1964–85), there are no studies about the advertising campaigns through the lens of gender.Footnote 8 This article demonstrates how the male creators of the advertising campaigns constructed the image of the ideal Brazilian woman as a white middle-class ‘housewife’, which operated within the traditional gender norms the government sought to reinforce.Footnote 9 It shows that gender analysis can provide new interpretations of economic policy-making. Finally, this article emphasises the social reaction to the campaigns from Brazilian citizens,Footnote 10 especially urban women, and the political reaction from the opposition Movimento Democrático Brasileiro (Brazilian Democratic Movement, MDB) policy-makers, who used the campaigns to criticise the military regime. The campaigns ultimately contributed to the erosion of support for the regime among certain sections of civil society.

The Military's Propaganda Efforts and the Use of Advertising in Politics

Private and public propaganda institutions alike were founded in Brazil in the 1960s. The Instituto de Pesquisa e Estudos Sociais (Institute of Research and Social Studies, IPÊS), funded by Brazilian businesses, American corporations and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and linked to the military, carried out propaganda efforts to destabilise the left-wing government of João Goulart.Footnote 11 After the coup in March 1964, the new regime created its first official propaganda institution in January 1968 when the Artur da Costa e Silva regime (1967–9) established the Assessoria Especial de Relações Públicas (Special Public Relations Consultancy, AERP). Financed by the state and run by military officers, the AERP described its campaigns not as ‘propaganda’, or advertising, but rather as ‘social communication’.Footnote 12 The regime of Ernesto Beckmann Geisel (1974–9) later rebooted the AERP into the Assessoria de Relações Públicas (Public Relations Consultancy, ARP).Footnote 13 The military regimes also enlisted the help of Brazil's private advertising agencies in the Conselho Nacional de Propaganda (National Advertising Council, CNP).Footnote 14

The civil–military dictatorship used advertising as a main policy lever to legitimise its rule, and its campaigns sought to shape people's perceptions about their government, their lives and their futures. Beginning in 1971, Colonel Octávio Costa, the head of the AERP, championed the government's ‘social communication’ campaigns, which aimed to sell a positive vision of Brazil.Footnote 15 These campaigns emphasised values such as family, love and solidarity; health and education issues such as vaccinating children and preserving fuel; and social ideals such as the hardworking self-made rural man.Footnote 16 They sought to create a ‘climate of optimism’ that served, in both Brazil and abroad, as a smokescreen for the regime's repression of targeted social groups.Footnote 17 Though Brazil's leading private advertising agencies eagerly collaborated with the regime on these campaigns, hardliners in the military advocated for more overt and aggressive propaganda instead of Costa's subliminal and peaceful campaigns, and there were frequent conflicts within the regime about Costa's efforts.Footnote 18 Some campaigns also directly supported policy objectives. The 1969–70 campaign ‘Brazil: love it or leave it’ supported the São Paulo businessmen-funded Operação Bandeirante (Operation Bandeirante, OBAN), which violently targeted ‘subversives’ and led to state-sponsored terror.Footnote 19

Advertising is in fact one of the most important tools in modern politics, and all regimes along the spectrum from authoritarian to democratic use it.Footnote 20 Advertising seeks to alter people's beliefs, desires and actions, often subliminally.Footnote 21 A private corporation can use it to increase demand for its product among a specific group of people, and a government can use it to increase demand – the social support that crystallises into social legitimacy – for its policies. Advertising serves as an effective policy tool because it can produce support for a political regime even if that regime maintains contradictory policies. If, however, the beliefs an advertising campaign tries to instil clearly contrast with the targeted population's lived experience, the campaign can produce the opposite effect of that intended.

The Economic, Political and Social Context of the 1973 Campaign

Finance Minister Antônio Delfim Netto helped guide Brazil through several years of sustained economic growth, a period dubbed the ‘Brazilian economic miracle’. From 1968 to 1973, real GDP grew by an average annual rate of 11.2 per cent and manufacturing at a rate of 13.3 per cent.Footnote 22 Moreover, annual inflation remained relatively stable at between 15 and 27 per cent, though it was on an upward trend beginning in early 1972.Footnote 23 Delfim Netto achieved these results with direct government intervention in the economy through price controls and loose fiscal, monetary and credit policies.Footnote 24 A massive influx of foreign capital investment also powered the economic growth. Though this capital inflow made up for current account deficits, it also caused Brazil's debt to balloon. The country's gross external debt more than quadrupled between 1967 and 1973 from US$3.4 billion to US$14.9 billion.Footnote 25 Delfim also maintained a restrictive wage policy featuring Mário Henrique Simonsen's wage formula, which he wrote in 1964 for the Programa de Ação Econômica do Governo (Government Economic Action Programme, PAEG) as part of Minister of Planning Roberto Campos's technical team. The policy reduced real wages by design to force Brazil's workers in the urban formal sector to disproportionately shoulder the burden of the anti-inflation fight and to redistribute their income to their employers to increase private savings rates.Footnote 26 As a result, both inequality and some measures of poverty grew during the years of economic expansion.Footnote 27

These years of economic growth occurred within the context of the authoritarian civil–military dictatorship's violent crack-down on dissent. Due to several years of the wage squeeze and economic hardship, social opposition to military rule grew in 1968. Workers, students and elements of the Catholic Church protested against the regime's policies in strikes, marches and public speeches, which the military violently repressed.Footnote 28 In December 1968, responding to the social protests, the Costa e Silva regime passed Ato Institucional 5 (Institutional Act 5, AI-5) through which it censored the media, jailed journalists, and forcibly retired judges, congressmen and professors.Footnote 29 The Costa e Silva regime and the subsequent Médici regime also used AI-5 to institutionalise state violence and torture.Footnote 30

Amidst this repressive environment, in a speech to the nation on 31 March 1972, President Médici decried the returning problem of inflation in Brazil. Though Delfim Netto's economic policies were increasing economic growth, they were also causing a resurgence of inflation due to both bottlenecks from the economic expansion and distortions caused by price controls.Footnote 31 Médici called for a shift in economic policy from one that achieved economic growth while tolerating inflation to one that reduced the surging inflation while also maintaining high rates of economic growth.Footnote 32 The regime sought low and stable inflation to shore up the social legitimacy it needed to continue its rule without real democratic checks and balances. Médici's renewed focus on inflation was also an unmistakable criticism of Delfim Netto. The policy shift implied he had failed to control inflation, putting the future of the dictatorship in jeopardy.

The need to reduce inflation as the main policy objective was partially self-inflicted. Ever since the 1964 coup, the military regime had advanced the narrative that the post-WWII ‘populist’ governments of Getúlio Vargas, Juscelino Kubitschek and João Goulart had recklessly created inflation, which had nearly resulted in a communist takeover. In this narrative, inflation and social strife were synonymous with leftists whereas order, progress and economic growth were synonymous with the military. The urban middle and upper classes who supported the military feared a return of inflation, and by extension social chaos. An increasing inflation rate would not only distort relative prices and negatively impact Brazil's ability to attract the foreign capital investment it needed to finance its economic development; more importantly, it would also threaten the regime's fragile social basis of support because the narrative it had been selling to the Brazilian public for almost a decade stressed its ability to control inflation. Moreover, despite the regime's repression of workers, students and others deemed ‘subversive’, social opposition never ceased, and in the early 1970s there were renewed strikes and civil society resistance.Footnote 33

By the end of 1972, Delfim Netto had a decision to make. He faced inflationary pressures due to his own economic policies, burgeoning social unrest, and political demands to do something about the growing inflation problem. Médici established the difficult policy objective of both lowering inflation and growing the economy at the same time. To achieve economic growth, Delfim continued to directly stimulate the economy with a range of fiscal, monetary and credit policies.Footnote 34 Yet these policies also caused inflation. And even though inflation hovered at around 20 per cent in 1970, 1971 and 1972, Delfim unrealistically stated in public in 1972 and even as late as April 1973 that the government would achieve an inflation rate of 10–12 per cent in 1973.Footnote 35 Unable to employ economic policies to reduce inflation because they would stunt growth, he turned to advertising.

Advertising Campaign of 1973: ‘Say No to Inflation’

On 9 April 1973, Delfim Netto held a meeting with members of the CNP at the Copacabana Palace Hotel in Rio de Janeiro to announce the new government effort to fight inflation. Present at the meeting were luminaries of the Brazilian advertising world such as Mauro Salles and José de Alcântara Machado. Delfim and advertising professionals had previously discussed planning an advertising campaign, and the campaign was ultimately the result of a combined effort of the largest private ad agencies in Brazil.Footnote 36 Offering their services for free, McCann-Erickson, DPZ and MPM worked on the creative side, Alcântara Machado covered production, Dension carried out PR, and Mauro Salles/Inter-Americana dealt with placement.Footnote 37 Joel La Blanca, the executive director of the CNP, stated that the campaign ‘is one of the measures that will make the proposed goal of 12 per cent inflation viable in 1973’.Footnote 38 Launched with much fanfare, the ‘Say No to Inflation’ campaign was the largest advertising campaign in the history of Brazil until that point.Footnote 39

Lasting from April to August 1973, the campaign sought to teach Brazilian consumers how to shop correctly as a way to fight inflation. It circulated 100,000 posters and another 100,000 leaflets with the simple text ‘Say No to Inflation’ throughout multiple Brazilian cities and then strategically placed several print advertisements in the highest-circulating newspapers.Footnote 40 La Blanca described the underlying logic of the campaign: ‘The central idea behind this campaign […] is really that all of us are responsible for inflation, at least to the extent that it is accentuated by attitudes of passive acceptance of price increases or passive acceptance of the necessity to increase prices.’Footnote 41 Delfim Netto asserted that ‘the mechanism that generates inflation, principally in its current phase, has a large psychological component, [which] is probably larger than the economic influences’.Footnote 42 Yet the campaign targeted only food and other consumer goods and left a large portion of total consumer spending untouched, including housing and electricity. Moreover, by focusing on consumers and shopkeepers, the campaign did not touch the producers and wholesalers who set a large part of the prices of many goods before they arrived in urban retail outlets. The campaign thus affected only a small portion of the larger problem of inflation.

The campaign had two targets: women and small shopkeepers. It sought to teach women, whom it referred to as ‘housewives’ (donas de casa), that they had the power to prevent shopkeepers from charging high prices by shopping at different stores.Footnote 43 As Delfim Netto put it: ‘We want to show that [housewives] should not be slaves to their butcher or grocer, and that the best way to end abusive prices is through market research.’Footnote 44 La Blanca claimed that ‘a housewife can have considerable influence if she is induced to accept the idea that she has in her hands, with her decision to buy wherever she wants, the power to resist unacceptable price increases’. The campaign implied that small shopkeepers, the urban retailers such as butchers, grocers and bakers, caused inflation because they persistently raised prices. But, as La Blanca bemoaned, ‘commerce entails a group of shops and people that are difficult to handle and control through central measures’. For that reason, he continued, ‘stimulating housewives to buy carefully is, evidently, an effective tool to provoke non-inflationary attitudes in commerce’.Footnote 45

The responsibility for inflation in Brazil and the burden for its defeat, in short, did not lie with the men in the federal government who enacted budgets and fiscal, monetary and price policies, nor with the male landowners, intermediaries, or wholesalers who raised the prices of food items, at times artificially, before they arrived in small urban shops. Rather, the responsibility lay with ‘housewives’ who had to be taught how to shop correctly, as well as with small shopkeepers who would be forced to lower their prices due to these women's new-found actions. In effect, the campaign served as a way for Brazil's policy-makers to redirect responsibility for the inflation problem onto the Brazilian people. Delfim Netto enlisted the help of the country's advertising professionals to design an advertising campaign that would blame women and shopkeepers for inflation to distract from his own policy failures and to make it appear he was doing something to address the problem.Footnote 46

In their targeting of ‘housewives’, Delfim Netto and the advertising professionals, all of whom were men, mobilised a series of beliefs, assumptions and tropes about women that operated within the traditional gender roles the civil–military dictatorship sought to reinforce in Brazilian society. Since the early twentieth century, Brazil witnessed repeating cycles of rapid economic change, with women challenging gender norms, and then men seeking to reinforce traditional gender roles. In the two decades after World War I, the old pattern of patriarchal authority within the rural extended family gave way to the ideal of the urban nuclear family as women openly challenged gender norms, which led to a backlash from men.Footnote 47 Getúlio Vargas’ Estado Novo (New State) (1937–45) sought to re-instil traditional gender roles, whereby men were supposed to earn a wage whereas women were supposed to be housewives in charge of the home who raised children.Footnote 48 Men of all social classes shared these normative gender beliefs, and the state, allied with private industry, founded institutions to promote traditional gender norms.Footnote 49 From 1946 to 1964, many urban women challenged gender norms, especially in leftist social movements protesting against the high cost of living.Footnote 50 During these years, male policy-makers often scapegoated women for economic problems, such as when Finance Minister Horácio Láfer implicitly blamed ‘housewives’ for the high cost of living in 1953.Footnote 51 After the military coup in March 1964, the new regime sought to reinforce traditional gender roles.Footnote 52 Yet in the early 1970s, partially due to the regime's own policies, many white middle- and upper-class women received university degrees and higher-status jobs.Footnote 53 There was also an expansion in single motherhood.Footnote 54 Moreover, feminist movements in the United States and Europe became increasingly visible. Though Brazilian feminism arose within this global context, it mainly developed as part of the social opposition to military rule.Footnote 55 Women's prominent presence in both guerrilla warfare and public protests challenged the traditional gender roles the military regime promoted.Footnote 56

The 1973 advertising campaign was part of the civil–military dictatorship's backlash against Brazilian women who openly defied the regime's gender ideology. The campaign constructed the image of the ideal woman as a white middle-class ‘housewife’ who managed the family budget and conducted the shopping for her family. It thus did not acknowledge black and mixed-race women of all classes nor poor and working-class white women. Delfim Netto and the advertising professionals used the term ‘housewife’ because it evoked tropes about women as non-threatening and easily manipulated by men, and they hoped that both men and women would identify with this gendered construction. The campaign then implicitly blamed this constructed image of women for the inflation that ravaged the Brazilian population. It sought to sell to women the belief that it was their fault if they did not find food items at low prices, because they would then be failing to fulfil their prescribed social role.

Newspapers interviewed women about the campaign before the print ads rolled out nationwide, and many women reacted negatively because the normative beliefs and actions the campaign sought to instil clashed with the constraints they faced in daily life. One woman in São Paulo stated that ‘the need to consult prices suggested by the government's campaign is not new, since we do this whenever we can’. She then expressed her displeasure with the campaign, saying ‘this is a difficult suggestion to accept because you never have time to research the market’.Footnote 57 Other women in São Paulo asserted that large distances between vendors and bad traffic prevented them from following the campaign's advice to shop around.Footnote 58 Women's household labour, including childcare, also made it impossible to spend extra time searching for the best prices. Dona Vilma dos Santos replied that the campaign would not work because of a ‘lack of time, mainly because of the children we raise that take up all of our time’.Footnote 59 Plus, some claimed that shopping at different stores was immaterial because, as one woman put it: ‘I already buy well, only I do not pay cheap […] because prices are so high everywhere’.Footnote 60

Other women described how issues of inequality would doom the campaign. One woman, whom Folha de São Paulo characterised as ‘leaving the supermarket in a hurry to pick up her son from school’, stated that ‘I have a car [yet I] don't have time during the day [to shop] – what will it be like then for housewives who do not have a car’?Footnote 61 Another interviewee, Dona Sílvia, summarised how many urban women in Brazil must have felt about the campaign:

I think the government's campaign can work only for those who have a car and do not work. I, for example, know about the campaign, but I cannot follow the suggestion of consulting prices before buying as a means of fighting inflation. Simply because I work, I study, I have to pick up my kids from school and I'm still the homemaker. I hardly have time to go to the supermarket, and when I do go, I'm always in a hurry. I grab the goods from the shelves, I pay, I run. I think the vast majority of housewives are in this situation.Footnote 62

Dona Sílvia emphasised she not only had to fulfil her normative gendered role as the caretaker of her family and children, but also that she had to work. For most urban Brazilian women, being a ‘housewife’ meant fulfilling both of these roles. Dona Sílvia showed that the campaign's gendered expectations conflicted with her lived experience. As a result, the beliefs and actions the campaign sought to instil fell flat and resulted only in angering some of its target population.

Jornal do Commercio, the leading business newspaper in Rio de Janeiro since the nineteenth century, likewise criticised the campaign for its misguided blaming of ‘housewives’ and consumers for Brazil's inflation problem. An editorial argued that to justify the campaign, the government ‘is inverting all the rules of the economic game, saying that the fight must take place first in the minds of men and then take place in the market’. In its opinion, this inversion was a distraction from the true party responsible for inflation: the government and ‘the evils of [its] commercial policy, which causes the price of a product to reach the consumer market many times higher than the price paid to the producer’. It concluded with the simple question to the government: ‘How do you transfer to the consumer the responsibility of saying no?’Footnote 63

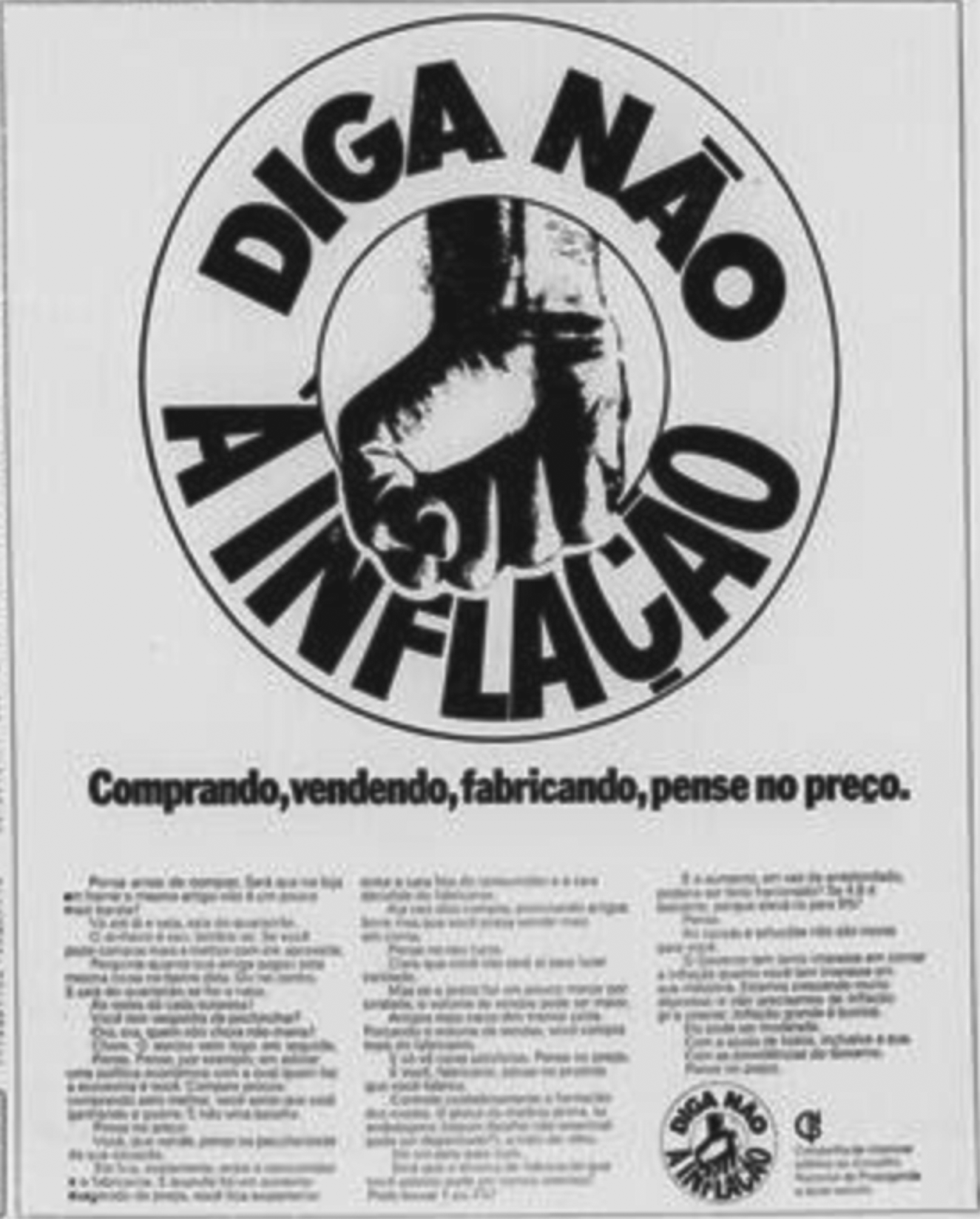

Amidst the largely unfavourable initial reactions to the campaign, the print advertisements started to appear throughout urban Brazil. One ad, shown in Image 2, features the campaign logo's large and menacing downward-thrusting fist. The ad directs different commands at its two audiences of women and shopkeepers. Likening adult women to breast-feeding babies, the ad asks women: ‘Are you ashamed to bargain? Well, well, who does not cry does not suckle! Cry. The smile comes soon after.’ Shifting to its next target, the ad instructs shopkeepers to ‘think of your profit. Of course you are not there for charity. But if the price is a little lower per unit, the sales volume may be higher.’ The ad concludes with an attempt to discursively connect women, shopkeepers and all Brazilians with the government in the fight against inflation. The last several lines declare: ‘We are growing very fast and we do not need inflation to grow. High inflation is stupid. It can be moderated. With the help of everyone, including yours. With the government's measures. Think of the price.’ Supporting the campaign's strategy, the ad implicitly places all Brazilians on the same level, with the same degree of responsibility for inflation, as the Brazilian government.

Image 2. Advertisement: ‘Buying, selling, manufacturing, think about the price.’

Source: Correio da Manhã, 30 April 1973, p. 4.

The advertising campaign then addressed its primary target of urban women with several new advertisements. One ad advocated for women to sexualise themselves to achieve the government's goal of reducing inflation. In Image 3, the ad with the tagline ‘Be a woman, bargain’ shows a white woman wearing a décolleté blouse, with a sensual look and pouting lips. Addressing women, the ad asserts that ‘you do not need to feel ashamed’ for bargaining; instead, ‘you should be happy when, with charm and talent, you succeed in bargaining a good discount’. The copy then reads: ‘with charm you open the smile of the owner of the lingerie shop’, who was evidently a man (‘dono’). Emphasising the campaign's goal of indirectly pressuring shopkeepers to lower their prices by targeting women's actions, the text states: ‘And with your talent you can show all of them how a friendly low price is good.’ The ad concludes: ‘[After bargaining] there will be more money left in your hand. And with more money you can buy more things. And the country can better control inflation with this. This is a mission for people who understand economics. And no one better than you, […] a woman.’ The ad called on women to carry out their prescribed social role as the shopper for their families while also using sexualised imagery and text that, hypocritically, conflicted with traditional beliefs about housewives. It also sought to teach women how to buy non-essentials like lingerie, whose impact on overall inflation was negligible.

Image 3. Advertisement: ‘Be a woman, bargain.’

Source: Jornal do Brasil, 13 August 1973, 1o Caderno, p. 8.

The final print advertisement of the 1973 campaign played upon traditional stereotypes about women. Image 4 shows the ad with its tagline ‘A woman looks prettier when she bargains and pouts.’ The image features a young white woman pouting her lips while tilting her head slightly to the side. According to the campaign's advertisements, in short, inflation would be defeated in Brazil by urban housewives sexualising themselves in front of male shopkeepers.

Image 4. Advertisement: ‘A woman looks prettier when she bargains and pouts.’

Source: O Bairro, 7 November 1973, cited by Monteiro, ‘O movimento’, p. 129.

Notably absent from the print advertisements were the mostly black or mixed-race domestic servants who did much of the shopping for urban middle- and upper-class women, as well as for their own families. By constructing the image of the ideal Brazilian woman as a white middle-class housewife, the advertising campaign simply failed to acknowledge non-white women. The campaign fitted neatly within the military regime's normative racial ideology. Facing a growing black consciousness movement in the 1970s, the regime was an ardent promoter of the theory of racial democracy.Footnote 64 This theory argued that Brazil had neither a racial discrimination nor a race problem.Footnote 65 One way the regime affirmed racial democracy was by erasing notions of racial difference, such as when it removed the question about race from the 1970 census. As such, excluding all depictions of black and mixed-race women from the advertisements tacitly promoted its racial ideals.

Though many women reacted negatively to the advertisements, some actively supported the campaign. In May, the government coordinated a three-phase programme with the Instituto Superior de Cultura Feminina (Higher Institute for Women's Culture) in Rio de Janeiro to get women on board. In the first two phases, women looked for price differences in basic food items in stores and carried out a survey of local shops.Footnote 66 The final phase was a symposium about the cost of living featuring hundreds of women participants as well as technical representatives from several government ministries.Footnote 67 Correio da Manhã reported that ‘the women, all housewives’ would learn from the officials how to help the campaign ‘with the goal of […] teaching the population all the ways to buy the best [item] for the most just price’.Footnote 68 The same paper also clarified that ‘the symposium is not a feminist movement’.Footnote 69 Reflecting on the event, Minister of Agriculture Moura Cavalcânti thanked the women – whom he referred to as ‘girls’ – for their participation and asked them to continue checking prices to achieve the campaign's goals.Footnote 70

As the ‘Say No to Inflation’ advertising campaign rolled out its print advertisements, many Brazilians turned to humour to mock it. One newspaper columnist wrote, ‘when I saw the posters scattered throughout the city, I imagined a campaign of throwing money away’. He continued: ‘They said only: “Say No to Inflation.” And it made me want to respond: No, inflation – and it's done. It seemed like a campaign such as: do not put your hand in the fire, do not get pneumonia, do not stop breathing, something like that.’Footnote 71

O Jornal interviewed residents of the north and south zones of Rio de Janeiro about the campaign, and it was clear it was off to a bad start. The newspaper found that the majority of people interviewed did not know what the word ‘inflation’ meant. The owner of a grocery store responded, ‘I really do not know what inflation is’, before adding that ‘there is nothing cheap. Those who can, eat, those who cannot, look.’ Factory worker Geraldo Setembrino said, ‘What do I understand by: “Say no to inflation”? I don't know.’ Confusion about the meaning of inflation even led to comical responses. A woman who did not give her name but identified as a ‘believer’ declared that ‘my religion does not allow us to talk about these sexual matters’. Those who knew what ‘inflation’ meant also responded negatively. Urila Rabello, a secretary, claimed that when she tried to search for better prices, ‘I did not see much difference.’ Walter Moura, an engineer, responded: ‘The campaign does not have a purpose. It errs from the beginning because the consumer does not cause inflation. They are changing the effect for the cause as the consumer cannot influence anything.’Footnote 72

Despite the negative sentiments among many urban dwellers, certain shopkeepers initially came out in favour of the government effort. The president of a retailers’ association, Jorge Geyer, was paraphrased stating that ‘the campaign “Say No to Inflation”, which has the support of Minister Delfim Netto, should deserve maximum collaboration from Brazilian shopkeepers’.Footnote 73 This same group of people soon soured on the campaign, though, stressing the disproportionate burden they shouldered and the implications that they were dishonest.Footnote 74 Geyer himself later referred to the campaign as ‘a large non-voluntary contribution by shopkeepers’.Footnote 75

As residents of Rio de Janeiro and small businessmen registered their dismay, federal deputies from the opposition MDB criticised the ruling regime by condemning the advertising campaign in the Chamber of Deputies. Many deputies criticised the government for blaming the Brazilian population for its own policy shortcomings. Deputy Laerte Vieira stated that ‘it is not the people […] that can solve the economic problems of the current government – [the] government is responsible for conducting economic policy’. Continuing, he reproached the regime for blaming ‘the people who suffer, who see an increasing cost of living each day’, and he asked rhetorically, ‘will it be fair to say to the wage-earner, whose purchasing power is continually reduced: “Inflation will end if you want it to”?’Footnote 76 Deputy Florim Coutinho angrily declared that ‘it will not be through “bargaining” that someone will “say no to inflation”’, affirming that ‘it is not the people, the consumer, who provokes inflation’.Footnote 77

Other deputies rebuked the civil–military dictatorship about what it sought to sell to the Brazilian population as its strengths: the ‘economic miracle’ and the relative success in taming inflation since 1964. Deputy Peixoto Filho flatly stated in Congress that ‘the government is losing the battle against inflation’. Despite the advertising campaign and other publicity efforts, Peixoto Filho claimed that he or she ‘who receives wages, knows that, Mr. President. Housewives know it too.’Footnote 78 Referring to the campaign as ‘tiresome and monotonous because it does not correspond to the tragic national reality’, Deputy Amaury Müller directly attacked the symbol of the ‘economic miracle’. He posed the question: ‘Will it be necessary to say more to characterise the “Brazilian miracle” as a fantastic myth? – Or maybe, the truth, just for being true, is a forbidden word?’Footnote 79 A few weeks later Deputy Müller continued to criticise the campaign, saying that, along with a growing GDP, Brazil had ‘an unjust distribution of income, poverty and unemployment’, which provided ‘undisguised symptoms that the country […] remains on the edge of the abyss’.Footnote 80

Building upon these criticisms, Deputy Fernando Lyra criticised the government for how the advertising campaign denigrated Brazilian women. Asserting his moral authority, Lyra referred to himself ‘as the head of a family’ before condemning the advertisements’ ‘demeaning insinuations for the dignity of women’. He particularly condemned the ad reproduced in Image 4 above.Footnote 81 Deputy Lyra's criticism sought to undermine the regime's attempts to portray itself as the guardian of traditional gender norms and the nuclear family.

International events soon overtook the advertising campaign. In October 1973, after war broke out in the Middle East, the OPEC oil embargo caused a sharp rise in oil prices. By March 1974, the price of oil had quadrupled. What has since become known as the Oil Shock of 1973 added fuel to the fire of failure that engulfed the ‘Say No to Inflation’ advertising campaign. The campaign did not, however, need an external event to precipitate its failure. Prices continued their upward trend throughout 1973 well before the inflationary effects of the Oil Shock were felt. Moreover, it also failed in its attempt to stimulate the belief that women and small shopkeepers were to blame for the inflation problem, intended to distract from the government's policy shortcomings. Yet instead of admitting defeat, Delfim Netto manipulated the official inflation rate in 1973 to appear lower than the true rate.Footnote 82

The Economic, Political and Social Context of the 1977 Campaign

As the ‘Say No to Inflation’ advertising campaign fizzled out, the incoming Ernesto Geisel regime (1974–9) confronted an uncertain economic, political and social environment. Economically, the regime faced several structural distortions from the excesses of the ‘miracle’ years in addition to the oil price increase.Footnote 83 Because Brazil imported roughly 80 per cent of its oil, the higher prices stressed the current account and budget.Footnote 84 In addition, the new regime sought annual GDP growth rates of 10 per cent through large investments in industry as detailed in September 1974's II Plano Nacional de Desenvolvimento (Second National Development Plan) (1975–9).Footnote 85 On the political front, MDB candidates made a strong showing in the October 1974 elections for Congress and state legislatures, which was a clear rebuke for military rule.Footnote 86 Moreover, social movements renewed protests in Brazil's largest cities, putting pressure on the Geisel regime and its policy of gradual political liberalisation known as distensão. These protestors continued to weather violent crackdowns, including arbitrary detentions, torture and murder.Footnote 87 This political and social atmosphere rendered any recessionary economic policies untenable. Like Delfim Netto before him, the new Finance Minister Mário Henrique Simonsen faced the need to achieve high rates of economic growth while also controlling inflation.

Simonsen and the Geisel regime opted for debt-financed economic growth with inflation instead of a harsh adjustment that would have reduced growth. Though Simonsen intermittently attempted to fight inflation, whenever the inevitable recessionary effects of these policies were felt, he quickly changed course and greased the economic wheels again.Footnote 88 In the years after 1973, renewed inflation accompanied GDP growth, throwing into question the narrative the military leaders had used since 1964 to sell their authoritarian rule to the Brazilian people. Growth without high inflation now became growth with high inflation. The similarities to the Vargas and Kubitschek years were unmistakable. From 1974 to 1976, Brazil achieved high rates of GDP and industrial growth, and both reached double digits in 1976.Footnote 89 But inflation grew to 35 per cent in 1974, slightly declined to 29 per cent in 1975, and jumped to 46 per cent in 1976.Footnote 90 Brazil's foreign debt grew to finance this economic expansion. The gross external debt more than doubled from 1973 to 1976, from US$14.9 billion to US$32.1 billion, leaving Brazil vulnerable to changes in interest rates, exchange rates and international financial flows.Footnote 91

The Geisel regime faced similar challenges in 1977. Politically, the opposition MDB did well in the municipal elections in November 1976. The government faced the danger that the direct gubernatorial elections planned for 1978 could result in another defeat for the pro-regime Aliança Renovadora Nacional (National Renewal Alliance, ARENA). Attempting to ward off this possibility, in April 1977 Geisel used the arbitrary powers under AI-5 to shut down Congress, and he passed several constitutional reforms to cement ARENA in power. Censorship and repression continued, though students and other segments of civil society were becoming more brazen in their condemnations of the regime.Footnote 92 Compounding these political and social challenges, the Geisel regime carried out a slightly more restrictive, though ultimately moderate, monetary policy to correct some of the distortions its previous policies had generated.Footnote 93 As a result, economic and industrial growth slowed.Footnote 94 By mid-1977, facing these unfavourable conditions, Finance Minister Mário Henrique Simonsen had a decision to make. Any attempt to reduce inflation would negatively impact economic growth, and the Geisel regime needed a growing economy as a selling point for its authoritarian rule and policy of distensão. Given the interconnected economic, political and social constraints he faced, Simonsen took a page out of his predecessor Delfim Netto's book. He decided to blame Brazilian consumers, especially women, for inflation in a new advertising campaign.

Advertising Campaign of 1977: ‘People's Current against Inflation’ or the ‘Bargaining Campaign’

The Geisel regime announced the new advertising campaign, the ‘People's Current against Inflation’, in early September 1977. Featuring eleven short films for television and twelve radio spots, it was carried out in two phases.Footnote 95 The first, targeting consumer motivation by encouraging people to ‘bargain’, ran in October, and the second, the educational phase, sought to alter women's shopping habits by urging them to buy ‘substitute’ goods at lower prices and food items when they were in season, and to learn how to shop around instead of settling for high prices.Footnote 96 Harkening back to 1973's ‘Say No to Inflation’ campaign, regime officials aimed to discursively link the government and the Brazilian population in the fight against inflation, thereby limiting its own responsibility for the issue.Footnote 97 The Superintendência Nacional de Abastecimento (National Superintendency of Supply, SUNAB) supported the campaign with a tandem campaign known as ‘Defend Yourself’, which encouraged people to report businesses that charged prices above the official price tables. Colonel José Maria Toledo de Camargo, the head of ARP, stated that the campaign's audience was the middle-class consumer, whom he referred to as a ‘multiplier’ group.Footnote 98

The 1977 advertising campaign was the brainchild of Finance Minister Mário Henrique Simonsen. Simonsen came up with the idea for the campaign and asked his friend Roberto Medina and his agency Artplan/Premium to execute it.Footnote 99 Colonel Camargo recorded that Simonsen showed him an already finished advertising campaign in August 1977.Footnote 100 Though Camargo altered some of the messaging and even axed one planned TV spot he referred to as being in ‘bad taste’ (the ad showed a poor family in their humble abode during a storm, the wife struggling and finally giving birth to a baby, followed by the tagline: ‘If they managed to overcome so many difficulties, we will beat inflation!’), the original contours of Simonsen's campaign remained.Footnote 101 The use of technical terms from economics such as ‘substitute’ and ‘multiplier’ also revealed Simonsen's influence.

Given that the 1973 campaign did not lower prices and faced harsh criticisms, why did Simonsen decide to carry out a similar campaign? In effect, it was an act of desperation. The economic, political and social constraints he faced were insurmountable, and therefore advertising offered the only potential solution. If people internalised the campaign's messages and were occupied shopping around and bargaining, they would have less time to pay attention to the regime's own economic mismanagement and violence against dissidents. Yet the campaign bordered on the absurd. Just as in 1973, the campaign focused only on consumers and shopkeepers rather than the producers and wholesalers who set a large part of many goods’ prices before they arrived in urban retail outlets. In addition, even if all consumers altered their shopping habits, this would impact only a portion of total consumer spending. The campaign did not target the prices of fuel, electricity, telephones, medicine, or housing, which at the time often accounted for a majority of family expenditure.Footnote 102 Moreover, in 1977 between 60 and 70 per cent of the population of the cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo shopped at supermarkets for basic food items.Footnote 103 Because computers automatically fixed the prices at supermarkets, bargaining was impossible. The vast majority of total family spending, especially in the larger urban centres, thus remained untouched by the campaign. Karl Marx's quip about Napoleon and Napoleon III also applied to the Brazilian military regime mounting two anti-inflation advertising campaigns: ‘the first time as tragedy, the second as farce’.Footnote 104

Just as in 1973, women in São Paulo reacted negatively to the campaign before it began. Folha de São Paulo quoted Dona Landelina saying that bargaining would not fix the inflation problem, and she warned of the consequences if one drew attention to high prices. She stated:

Things are absurdly expensive. There is no use in bargaining. Only if everyone stopped buying, then yes, the prices would be resolved. But that is impossible. This is shameful. A poor man who earns the minimum wage and has four children, what does he do with Cr$1,000.00? But we cannot even complain. If you complain, you can end up in jail.Footnote 105

Her anger at the government unmistakable, Landelina stressed the difficulties the average working Brazilian faced while simply trying to survive. Other women asserted the government was responsible for fighting inflation, not them. Dolores Marigo was quoted saying, ‘there is no use in bargaining, it resolves little. Measures against inflation should come from above, from the government itself, not from the people.’Footnote 106 These women emphasised that the government's own policies prevented them from carrying out their gendered role of finding food items at good prices for their families. Their anger also revealed they did not internalise the regime's message that they were to blame for inflation. Instead, they openly blamed the government.

Small shopkeepers also came out against the campaign before it started. The president of a small business institution, Senator Jessé Pinto Freire, unequivocally asserted that ‘the bargaining campaign […] does not find support from Brazilian shopkeepers’.Footnote 107 Reiterating this view, João Narcisio, the president of another trade organisation, argued that not only would the campaign fail, but ‘it may [also] create difficulties between consumers and shopkeepers’. Narcisio then defended consumers against the campaign's patronising implications. He stated: ‘the consumer does not need bargaining campaigns […] because before making their purchases, they conduct market research’.Footnote 108

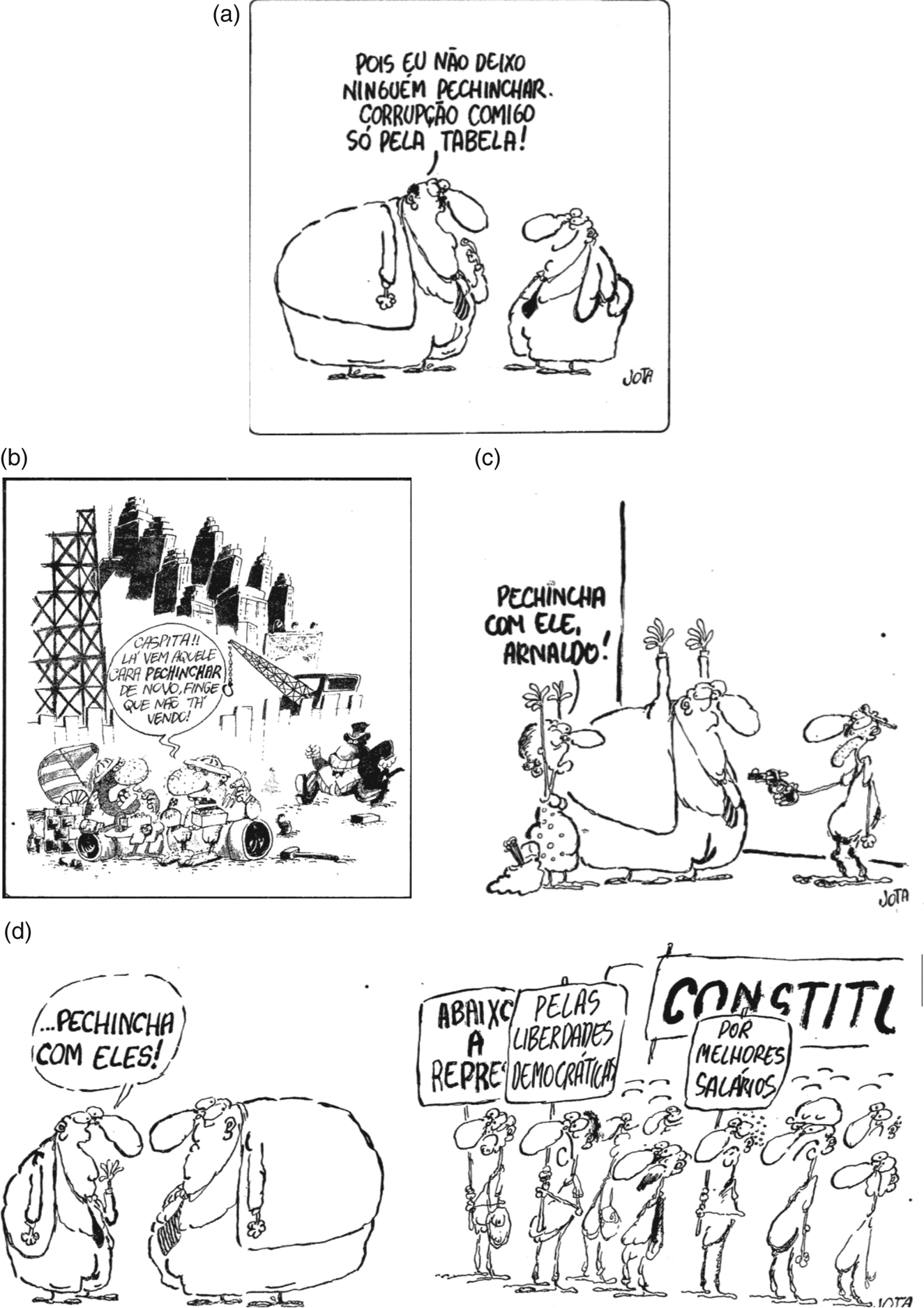

A few weeks after the announcement of the advertising campaign and a week before the ads were rolled out, Brazilian newspapers began to openly ridicule the campaign and by extension the Geisel regime. Folha de São Paulo published a series of cartoons (Image 5) that mocked the use of the verb ‘to bargain’ (pechinchar) in the campaign. (The 1973 campaign had also used this verb in the commands to women to bargain using their ‘charm and talent’ to get lower prices.) In one cartoon (Image 5a), a government bureaucrat says to a colleague, ‘Well, I do not let anyone bargain. The only corruption with me is with the price table!’ In another (Image 5b), two construction workers eating their lunch see a caricature rapacious capitalist running their way. One remarks to the other, ‘Caspita!! Here comes that guy to bargain again, pretend you don't see him!’ The third (Image 5c) shows a desperate robber pointing a gun at a man and woman with their hands up as the woman says, ‘Bargain with him, Arnaldo!’ Finally, in the last cartoon (Image 5d) a crowd of determined protestors hold up signs reading: ‘Down with repress…’, ‘For democratic freedoms’, ‘For better wages’, and ‘Constitu…’ Two well-dressed men look at each other, flustered, as one says to the other, ‘… Bargain with them!’ In an atmosphere still tense with repression and censorship, these cartoons revealed a civil society becoming bolder in its condemnations of the military regime.

Image 5. Cartoons from Folha de São Paulo.

Source: Folha de São Paulo, 25 September 1977, p. 17.

As these negative popular responses did not bode well for the campaign's success, Colonel Camargo lashed out at the media for stating it was all about ‘bargaining’. Camargo blasted newspapers and television stations for their ‘distortions’ about the campaign. Defensively, he affirmed there had been no valid criticisms: there was no ‘cause for protest, because we are not offending anyone’.Footnote 109 He later told the media: ‘This is not the bargaining campaign. Bargaining is just one topic. There are other more important topics such as the substitution of articles.’Footnote 110 It was clear the government had lost control of the message of the campaign before it even started.

The campaign's television advertisements began to appear on screens throughout Brazil beginning in October 1977. One TV ad rather explicitly blamed the Brazilian people for inflation because of their shopping habits. The voice in the film admonished:

Everyone complains about the price of rice, tomatoes and beans. But everyone keeps on buying and selling. And the cost of living continues to rise. No one does anything. Everyone keeps buying and selling as if nothing happened. Understand once and for all. The cost of living is all our fault. It is the fault of those who buy, and the fault of those who sell. You have to do something. Start to bargain. Start to value each cent of your money. Look for the cheapest item. Discuss the price. Buy only what you need. If everyone believes that this is the only solution, those who sell at high prices will end up believing it too. And Brazilians will beat inflation. Starting today, buy only what your money can afford.Footnote 111

The TV ad's message surely offended many Brazilians, especially considering that many people's wages had declined in real terms over the past decade – as a result of Simonsen's regressive wage equation from 1964 – while the prices for the basic items needed to survive seemed to continually increase. At the same time as people were struggling, the voice in the ad told the viewer that ‘the cost of living is all our fault’ and urged them to ‘start to value each cent of your money’.

Other TV advertisements advanced themes similar to those in the first ad as well as to those in the discredited 1973 campaign. One spot issued the command to its audience: ‘Start buying correctly, at the right time. It's simple.’ It then instructed Brazilian consumers to ‘swap the expensive vegetable for the cheapest one. Swap the expensive greens for the cheapest ones. Swap the expensive fruit for the cheapest one. Look around. Discuss the price.’Footnote 112 Another TV ad contained similar audio along with two additional patronising phrases: ‘Start valuing every cent of your money. Buy only what your money can afford.’Footnote 113 Perhaps responding to the public outrage generated by the campaign, another TV ad concluded with the statements: ‘You are not to blame for inflation. But you can help in fighting it.’Footnote 114 Yet another TV ad directed Brazilians to search for ‘substitute’ goods. The ad stated that if all consumers bought ‘cheaper’ items, then ‘expensive products […] are going to have to be priced right’.Footnote 115

After the advertisements were released, many Brazilians criticised the advertising campaign and the Geisel regime. A taxi driver in Rio de Janeiro told Jornal do Brasil: ‘Bargain? It's no use. The government ought to have bargained [down] the price of fuel internationally for us not to be paying these absurd prices for everything.’Footnote 116 Another newspaper article with the title ‘Bargaining campaign is not taken seriously’ reported that in the city of Curitiba someone ironically denounced the military for increasing prices.Footnote 117 Federal Deputy Oviedo Teixeira (MDB) said that ‘the Bargaining Campaign initiated by the government can only be seen as a joke’.Footnote 118 Columnist Carlos Eduardo Novaes magnified these critiques and emphasised the absurdity of an authoritarian regime asking the people it was repressing for help in fighting inflation. He wrote:

I am particularly suspicious of the campaign. The government has never convened us for anything. On the contrary: in the presidential elections, it even prefers that we stay at home. The government must be attempting a psychological blow: maybe while bargaining we have the feeling that Brazil is made by us. Either way, it is a show of weakness. It reveals that the government, always so well equipped to combat subversion, is not equipped to fight inflation. But let's not blame them. After all, there is only one government and it cannot fight so many things at the same time. At the moment, subversion is more important. According to the latest statements by the governor of São Paulo, there are currently more subversives than consumers in the country.

And speaking of bargains, why don't we also launch the Political Bargaining Campaign?Footnote 119

Some people openly mocked the Geisel regime. Sebastião Manoel Vasconcelos from Rio de Janeiro published a letter he sent to Colonel Camargo about the campaign. He wrote: ‘I asked him to teach me how to bargain at supermarkets, pharmacies, etc., establishments managed by citizens without decision-making power. I am still waiting for an answer.’Footnote 120 Others expressed outright hostility towards the government for the campaign that blamed them for inflation. In a letter to the editor, João Alfredo de Mendonça Neto encapsulated many people's feelings about the advertising campaign and the Geisel regime:

The Brazilian people have been disrespected and humiliated, through various means of communication, by the Bargaining Campaign, which affirms that inflation is the fault of all of us [original emphasis]. Now, if the people do not participate in the planning, execution and control of the country's economic policy, they cannot be summarily accused of any failures resulting from that policy. There exists right and wrong. Let us celebrate those responsible for successes, but also let us agree that only those who are truly responsible for errors be accused.Footnote 121

These forceful critiques of the military regime, more openly scathing than those made in 1973, showed that certain sections of Brazil's civil society were becoming less fearful of the government. They also revealed the degree to which Geisel, Simonsen, Medina, Camargo and other ministers had severely misjudged how people would respond to the campaign.

Building upon their initial opposition, shopkeepers harshly criticised the campaign for unfairly targeting them. In a letter to the editor, a small businessman called the campaign ‘nefarious and unjust’ and asserted that ‘the question that arises naturally is: can we bargain over [our taxes]?’Footnote 122 Another shopkeeper indignantly referred to the government's campaign as ‘an absurdity, [because] they want to throw on the backs of shopkeepers the cause of inflation’. Continuing, he raged: ‘I'm going to start bargaining over fuel; bargain so that universities do not increase [their fees] by 35 per cent; bargain over road tolls; bargain so that the government […] takes care of the social assistance of the people. Now I'm going to bargain too!’Footnote 123

At the same time as individuals, newspapers and shopkeepers criticised the advertising campaign, and just as in 1973, opposition politicians from the MDB used the campaign to criticise the ruling regime. Deputy Adhemar Santilo referred to the campaign as ‘insincere’ before asking rhetorically: ‘Bargain how? At the cash registers in Casas da Banha, Jumbo, Sears, Carrefour?’Footnote 124 Deputy Gamaliel Galvão contrasted the government's ability to engage in political repression with its inability to ‘limit the profits of the large traders [and] increase the wages of workers and public servants to give them the […] financial conditions to face the cost of living’.Footnote 125 Reinforcing these criticisms, Deputy Leonidas Sampaio rebuked the regime for being out of touch. He argued that ‘government advisers need to leave their offices and go to the open-air markets and supermarkets. They need to buy food with hard-earned money.’ He stated, bluntly, that ‘the people are hungry’.Footnote 126

Deputy Pedro Lucena described the perils of collaborating with the authoritarian regime on its advertising campaign. He recounted that a civil servant who reported to SUNAB that a business in Natal was quoting prices above the price table ‘was arrested and had to take 100 cruzeiros from his pocket to pay bail’.Footnote 127 Deputy Odemir Furlan criticised the Geisel regime by declaring: ‘The simplest formula for the culprit to defend himself is to accuse someone. And this is present in this bargaining campaign.’Footnote 128 Increasingly feeling the social and political pressure against the campaign, the Geisel regime even censored a critical editorial by O São Paulo, a Catholic weekly magazine.Footnote 129

Though some politicians from the pro-military ARENA initially supported the advertising campaign, they turned against it as it became increasingly unpopular. In mid-October, Deputy Siqueira Campos stated: ‘I consider [the campaign] as most fair.’Footnote 130 Yet less than two weeks later, Deputy Gerson Camata critiqued the Geisel regime for the campaign ‘that is providing so much opportunity for the MDB to criticise the government and for the caricaturists to sketch drawings alluding to the government’.Footnote 131 For Camata, the issue was not the content of the advertisements, but rather that opposition politicians and newspapers were using the ads to criticise the government. As the public criticisms grew louder and the campaign was widely considered a failure, Deputy Joir Brasileiro openly criticised the campaign. He asserted that the government should ‘forget for a moment the bargaining campaign – which has no other effect but to distract the people’ and instead focus on other issues Brazil was facing.Footnote 132 That the civilian leaders who provided cover for the civil–military dictatorship's violence turned against the regime and its advertising campaign proved that the campaign had become an albatross hanging around the government's neck.

Conclusion

The two anti-inflation advertising campaigns in 1973 and 1977 were attempts by an authoritarian regime to blame women, small shopkeepers and Brazilian consumers for a problem they did not cause and of which they were the main victims. Instead of taking responsibility for the inflation problem they helped generate, Finance Ministers Antônio Delfim Netto and Mário Henrique Simonsen enlisted the help of advertising professionals to carry out advertising campaigns to blame these groups for the problem. They mobilised normative gender, and racial, ideologies in advertising as a substitute for economic policies. Unsurprisingly, the two campaigns did not reduce inflation. Inflation increased during 1973 before the Oil Shock, and it maintained its elevated level throughout 1977 and 1978. In the following years, inflation exploded into hyperinflation, resulting in widespread turmoil. Nor did the campaigns succeed in their attempts to distract from the government's own policy failures. In contrast, as the social and political reactions show, the campaigns contributed to the erosion of support for the military among certain sections of civil society.

This article expands our understanding of state–society relations during authoritarian regimes, economic policy-making and advertising, and economic policy-making and gender. It provides a model for how to integrate political, economic, social and cultural approaches. Though economic history and gender history are often practised in isolation, this article illustrates the benefits of combining these frameworks. A purely economic history of inflation and policy-making in 1970s Brazil would overlook the non-economic policies that policy-makers used to address inflation, including advertising. In addition, the lens of gender provides insight into both the formulation of the advertising campaigns and the critical reception of the campaigns among Brazilians in general and women in particular. Given the findings in this article, I argue that it is essential to examine gender, and racial, politics when analysing economic policy-makers and economic policy-making.

This article also opens up avenues for future research about economic policy-making, advertising, gender and race. To what degree do economic policy-makers use advertising and gender and racial ideologies as substitutes for economic policies or to support economic policies? How does this vary by time and place? For example, in August 1974, the presidential administration of Gerald Ford in the United States carried out its own anti-inflation advertising campaign known as ‘Whip Inflation Now’ (WIN), which similarly did not reduce inflation and was widely criticised.Footnote 133 What is the relationship between the type of political regime and the use of advertising, and the type of political regime and the success of advertising, and how do these vary by time and place?

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Zephyr Frank, Alexandra Sukalo, Justine Modica, the JLAS editors and anonymous reviewers, and all the participants of the Gender History Workshop at Stanford University, especially Estelle Freedman, Liz Jacob, Christian Robles-Baez, Leo Barleta and Luther Cenci, for their comments on earlier drafts of this article.