For decades, Central America has been a key pipeline for cocaine flows between South and North America. But in the 2000s, what used to be a steady trickle suddenly turned into a flood. Today, traffickers move 86 per cent of the cocaine entering the United States through Central America.Footnote 1 With this shift came a surge in violence and a deepening of state corruption.Footnote 2 In response, journalists, policymakers, security experts and even some scholars started referring to this intensification of the drug trade and its violent collateral effects as the ‘Colombianisation’ of Central America.Footnote 3 The comparison with Colombia is particularly common among the military set. In 2005, for instance, Guatemala's Deputy Minister of Defence said, ‘The narco nexus may be stronger than the state now. There are areas where the army, police, local officials all work for narcotraffickers – it's like Colombia in the 1980s.’Footnote 4 A Spanish-language Google search, pairing ‘colombianización’ with ‘Guatemala’, ‘Honduras’, or ‘Centroamérica’, produces thousands of similar results.Footnote 5 The emergence of what we call the ‘Colombianisation’ narrative to describe Central America seems almost common-sensical: a harmless rhetorical shorthand for describing the persistence and propagation of the drug trade across space and time.

Our central claim in this commentary, however, is that the discourse of Central America's Colombianisation is not only simplistic and misleading, it is dangerous. It obscures the actual geographies through which narcotrafficking operates and, in doing so, enables the intensification of damaging drug war policies that achieve specific financial, geopolitical and political-economic ends benefitting an elite few. We build this argument across three sections. First, we explain how the narrative emerged as the Western Hemisphere's drug routes changed, and we give examples of its use, elaborating on what the discourse has come to signify. Next, we analyse the ways in which those significations mischaracterise drug war geographies and, thereby, naturalise and enable destructive, status-quo drug war logics. Third, drawing on empirical evidence from our own and others’ work, we recognise that there is a Colombianisation of Central America under way, but it is not, as security pundits suggest, an organic metastasis of some pathological criminality originating in South America. The real Colombianisation is a convergence of geopolitical and capitalist interests that have opportunistically seized upon the geographical realignments of the drug trade to expand the same military-agroindustrial nexus in Central America that proved so ‘successful’ in Colombia.

The spread of this destructive model of rural development brings together Colombia's military and agroindustrial expertise with the powerful financial muscle of some of its largest corporations. Our name for this convergence of militarisation, financialisation and agribusiness is the ‘military-agroindustrial complex’. By highlighting these relationships, our contribution here is not only to deconstruct Colombianisation as a discursive formation, but also to reveal the actual transnational connections and circulations that make the drug trade, the drug war, and their associated economies of violence possible. Ultimately, we conclude that what makes the Colombianisation discourse so misleading and dangerous is precisely the way it erases these connections and circulations.

As we understand it, the discourse of Colombianisation is not limited to the use of the term itself; rather, we approach it as a broadly constructed discursive formation that includes direct diagnostic comparisons about the similitudes of the drug problem in Colombia and Central America. Thus, in what follows, we use the term ‘Colombianisation’ not in reference to the concrete processes that the discourse ostensibly describes, but rather as the name of the discourse itself. Discourses, of course, are not ‘just words’. They are the socially produced and historically situated representations or statements through which we make sense of the world; discourses identify and construct problems in specific ways, enabling some understandings and courses of action while limiting others.Footnote 6 In this case, Colombianisation endorses prescriptive solutions to the problem of drug trafficking based on the assumption that the successful strategies applied in Colombia can and should be replicated in the isthmus. Colombianisation is what international relations scholars Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver and Jaap de Wilde call a ‘securitizing move’.Footnote 7 In their framework, securitising moves are alarmist discourses that frame a problem as such an existential security threat that the public becomes willing to accept extraordinary, emergency measures and sacrifices to address it.

Colombianisation is both a demand and a justification for extraordinary, repressive security measures against the growing existential threat posed by the drug trade. It claims that Central America, just like Colombia in the 1980s and 1990s, is falling apart, that its national governments are on the brink of collapse, and that society itself has descended into chaos – all thanks to the drug trade. Colombianisation is not the only reason behind the securitisation and militarisation of the drug war in Central America. But its power to push this securitisation and its ability to hide so much more than it reveals makes it particularly deserving of critical examination. Foreign interventions in Latin America have always drawn on discourses about the imminent political and economic collapse of its polities: from the Monroe Doctrine to the Cold War; from the Spanish–American War to the neoliberal revolution. US alarmism these days has seized on drug trafficking through dire warnings about the problems of narcoterrorism, ungoverned spaces, criminal insurgencies and state failure. ‘Colombianisation’ rolls all of these problematisations into a single, all-encompassing frame.

The ‘Colombianisation’ Narrative

The Colombianisation discourse emerged in the 2000s in the context of major shifts in the geography of hemispheric drug routes as traffickers adapted to US-backed crackdowns along the cocaine supply chain. The shifts gave Central American landscapes and drug trafficking groups a more prominent place in the global organisation of the trade.Footnote 8 As drug-related violence and disorder increased throughout the region, the claim that Central America had become the ‘new Colombia’ started gaining popular traction. Since then, all kinds of powerful public figures, from presidents to diplomats, columnists to news anchors, have perpetuated this discourse either by using the Colombianisation term itself or by drawing explicit historical parallels between contemporary Central America and Colombia in the 1980s and early 1990s. In the mid 2000s, Colombianisation also started including implicit and explicit suggestions about the way the South American country provided a desirable model for solving Central America's woes. Colombianisation not only signals that things in Central America are as bad as they were in Colombia, it also suggests that the region should mimic the militarised solutions that supposedly put the Andean country back on track.

Whether in its diagnostic or prescriptive guise, Colombianisation ‘conjures up images of … extreme corruption, violence, and mayhem’.Footnote 9 Guatemalan President Óscar Berger, for example, claimed in 2005 that his country had already been ‘Colombianised’, saying that ‘drug trafficking, organised crime, and the trafficking of arms and people’ had ‘seized this part of the world’.Footnote 10 Stratfor, self-proclaimed as the ‘world's leading geopolitical intelligence platform’, echoed Berger's claim, arguing that ‘organized criminal activities and a general collapse in security are resulting in the “Colombianisation” of Guatemala’.Footnote 11 An editorial published in 2017 by one of Guatemala's highest-circulation newspapers remarked, ‘The growth in drug trafficking, along with the ills that accompany it, in Guatemala and Central America have created a series of problems that amount to a Colombianisation. We are not blaming our Colombian friends; we simply see comparisons with the era of [drug lord Pablo] Escobar in that country.’Footnote 12

The discourse's more prescriptive side, which holds up Colombia as a policy-making model, is common within diplomatic and policy circles. An exchange between Texas Senator John Cornyn and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo during a 2019 congressional hearing on international drug control is illustrative. The senator called the counterinsurgency and anti-drug package known as Plan Colombia a ‘success story’ and asked Pompeo if it could serve as a blueprint for ‘a broader regional strategy’. Pompeo responded: ‘A Plan Colombia but more broadly for the region? Is that what you're thinking of? … That might make sense.’Footnote 13 Although repetition and ubiquity of a discourse are important for processes of securitisation, their adoption by powerful actors such as President Berger or Secretary Pompeo obviously have outsized weight and consequences.

Scholarly outlets have also contributed to the construction of this securitising discourse. As early as 2001, Foreign Affairs painted an almost Hobbesian portrait of the isthmus; it described the ‘chaos that the burgeoning drug trade has wreaked on the region’ and its ‘many maladies’ as the ‘“Colombianization” of Central America’.Footnote 14 One author defined Colombianisation as a generic term for the ‘disintegration of institutions – political, economic and social – and a permanent state of violent crimes such as political assassinations, executions, and human rights violations’.Footnote 15 Political scientist Patricia Olney similarly deploys the label without questioning or critiquing its sensationalism and empirical inconsistencies. In fact, she even endorses the view, first advanced by the US Army's Strategic Studies Institute,Footnote 16 that Central America's Colombianisation could make its violent street gangs part of a broader ‘Clash of Civilisations’. According to Olney, the growth of organised crime in the region has turned ‘traditional cultures and modern cultures’ against each other, sparking ‘a clash between those who oppose rule of law and those who are fighting to establish or maintain it’.Footnote 17 Unlike Olney, security specialist Sam Logan recognises some of the problems with the Colombianisation concept and yet still relies on its rhetorical effects to endorse the ratcheting up of militarised anti-drug efforts in Central America.Footnote 18

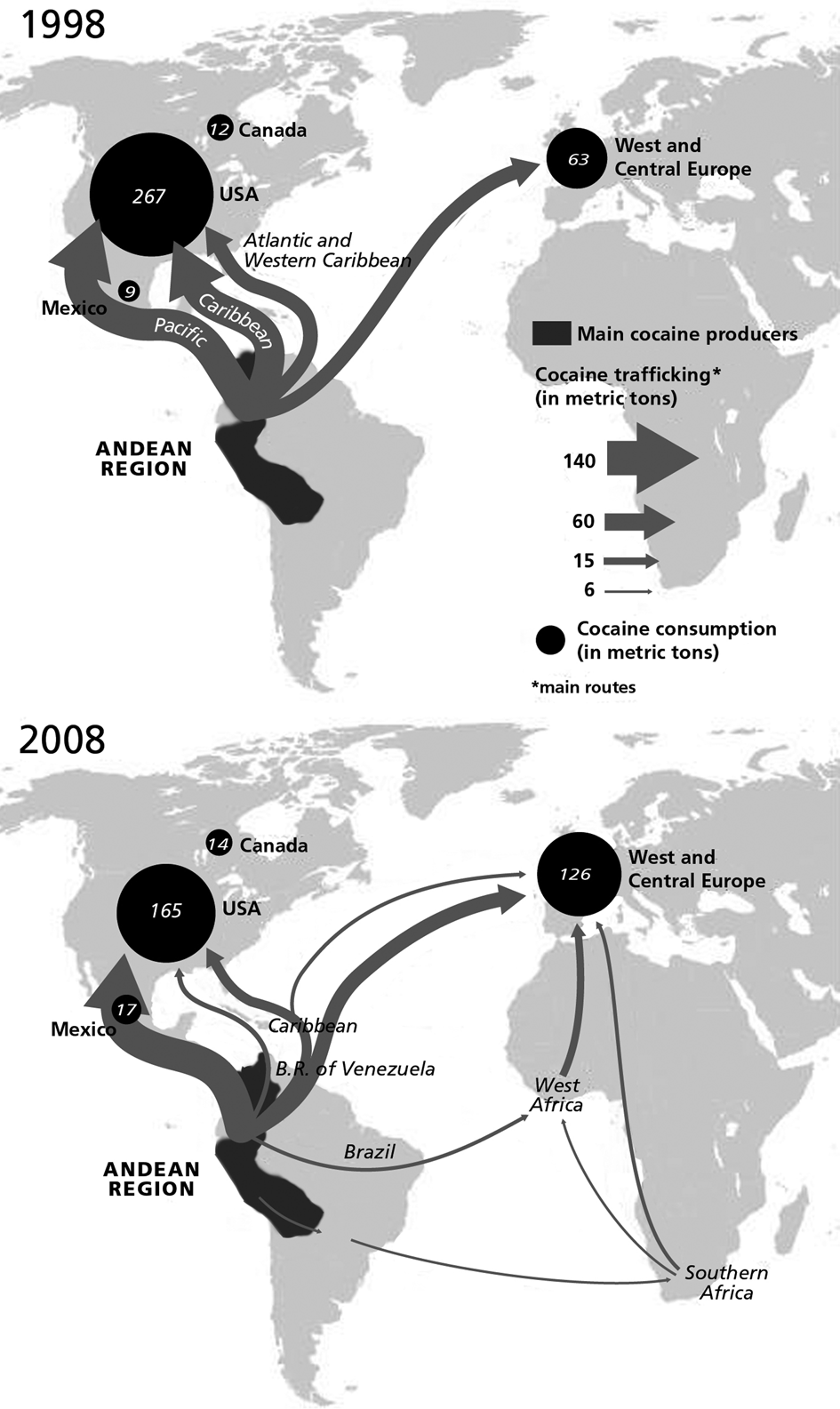

As used by the politicians, pundits and scholars cited above, Colombianisation implies a series of pathological traits – violence, organised crime, corruption, instability – that have autonomously moved from Colombia and infected Central America. The superficial geographical connections underlying Colombianisation have a visual analogue in the standard cartographic representations of the drug trade, as depicted, for example, in the UN's annual World Drug Reports.Footnote 19 This genre of maps typically shows a mess of arrows ominously swarming up from Colombia, through Central America and Mexico, until finally ‘penetrating’ the United States (see Figure 1).Footnote 20 The arrows are obviously simplified visual aids, but they are representative of broader geographical imaginaries about the drug trade as a series of disembodied ‘flows’ following a one-way, linear trajectory across bounded national spaces. The only suggested connection between places is the product (cocaine) that somehow propels itself from source to destination as if this happened entirely in thin air without any consequences for concrete social relations on the ground.

Figure 1. Map of Global Cocaine Flows by the UNODC.

Colombianisation assumes and perpetuates an even more spatially fetishised view of drug-trafficking networks than the obviously simplified representations made by maps. By spatial fetishism, we mean the way Colombianisation reinforces an understanding of drug trafficking as a monolithic enterprise endowed with a life of its own that exists and moves about independently of other social relations and processes. In this section, we identify three ways in which Colombianisation's spatial fetishism mischaracterises the geography of the drug trade by sustaining misleading geographical imaginaries and contributing to the securitisation logics of the drug war in Central America: first, it wrongly implies that the drug business entirely relocates from place to place; second, it elides the formative role of US drug policies while naturalising their predictable failures; third, it disconnects drug trafficking from broader and deeper political-economic problems.

Denial of the Drug Trade's Relational Geographies

In lieu of simultaneity and connection, Colombianisation compartmentalises and separates the two implicated places – Colombia and Central America – across both time and space: Colombia is ‘over there’ and ‘back then’ while Central America is ‘over here’ and ‘now’. This perspective de-historicises the drug trade and locks the spatiality of its ‘presence’ into a sequence of bounded spaces (first Colombia, then Central American nations).

The broad geographical outline of the actual cocaine commodity chain is simple. It begins in Colombia (where the vast majority of cocaine bound for the United States is sourced) with the production of coca leaves and their refinement into the drug. Colombian trafficking organisations and their Mexican counterparts negotiate the details of the export process, including routes, methods, prices and quantities.Footnote 21 With Central America as their transhipment zone, they typically leave the logistics of this leg of the journey to local, affiliated organisations that operate with varying degrees of oversight from their larger, more powerful patrons. In this way, drug trafficking has always connected a web of financiers, producers, suppliers, traffickers, money launderers, capos (drug lords) and runners across time and space.Footnote 22 What has changed in recent decades is the relative power of specific nodes and connections within that web. When the locus of power shifts within these networks so, too, does violence and corruption, which typically flare up wherever new trafficking routes are emerging, as agents on the ground fight each other for control while enlisting the complicity of local state and military officials. In other words, violence and corruption are endemic symptoms of a spatially fluid, adaptable and mobile (illicit) business model in which violence and bribery enforce contracts in the absence of law.Footnote 23

The Colombianisation narrative omits these ongoing connections between places by highlighting only the most shocking and sensationalist manifestations of the drug business as the sole indicators of its presence. This not only overlooks the relatively less violent spaces where the drug trade might be more thoroughly established and institutionalised; it also detracts attention from the ways drug-related violence and corruption are always, necessarily, produced through the interplay of the upstream and downstream dynamics of the commodity chain.Footnote 24 What happens in Central America is always and necessarily tethered to cocaine financing, logistics and supply in Colombia. The drug trade did not leave Colombia and re-emerge in Central America; in fact, if anything, Central America has helped Colombia's cocaine industry thrive. In this way, although Colombianisation seemingly emphasises geographical connection across Central and South America, it actually hides the relational geographies and interconnected histories of the drug war.

Naturalisation of the Drug War's Predictable Policy Failures

Another way that Colombianisation's spatial fetishism mischaracterises the drug trade is by obscuring the main driver behind its shifting geographies. Most glaringly, Colombianisation entirely leaves out the formative role of the United States. The omission of US policies makes the ravages of drug trafficking and their shifting geographies seem like a succession of unfortunate and disconnected events. What a massive body of scholarship shows, to the contrary, is that Central America's ascendance to prominence in the drug trade was neither natural nor inevitable; it was the direct result of the drug war itself.Footnote 25 The United States is the world's top consumer of cocaine and heroin as well as the global enforcer of the war on drugs, and both factors are crucial for understanding the changing geographies of drug trafficking over time in Latin America. The geography of drug trafficking is not only determined by the usual market forces of any global commodity – in this case, supply from South America meeting insatiable US demand – it is also shaped by the cat-and-mouse game of enforcement and evasion.Footnote 26 The sequence of crackdowns spurred by securitisation from place to place makes the geography of drug trafficking an especially dynamic and always-emergent process. As a veteran of the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) acknowledged after decades of futile efforts against this footloose adversary, ‘What we learned was that in drug work, nothing ever stands still.’Footnote 27

The definitive push for the US-led militarisation of the drug war in Latin America began in the late 1980s. Feeding off the media-induced panic over the so-called ‘crack epidemic’, the first administration of George H. W. Bush doubled down on the drug war, increasing its budget from US$6 billion to US$12 billion. And then, in 1989, Congress officially declared the Pentagon the ‘lead agency’ in charge of international US anti-drug efforts. This securitisation effectively turned the ‘war on drugs’ metaphor coined by Richard Nixon into an apt description of reality.Footnote 28 On the international front, the militarisation of the drug war involved a three-pronged attack: stepped-up efforts to interdict cocaine shipments then zipping across the Caribbean, more support to Andean militaries in the eradication of coca crops, and a decapitation strategy aimed at taking down the heads of the largest cocaine syndicates – most famously, Pablo Escobar. As critics at the time predicted, the ‘success’ of this militarised strategy of eradication, interdiction and decapitation entailed disastrous collateral effects.Footnote 29 Instead of reducing supply, curtailing shipments and crushing the cartels, the scale and scope of these problems simply multiplied.

By the time Bill Clinton settled into the White House, the drug war's seasoned warriors appeared to have finally got the upper hand: Escobar was dead; his main associates and competitors were also either dead or in jail; and coca cultivation had plummeted in Peru, which was then the world's largest supplier. But, with the drug trade, ‘nothing ever stands still’. In Colombia, the ‘success’ of the decapitation strategy, which took down Escobar in 1993, fractured the cocaine business. The relatively centralised and hierarchical structures of the Medellín and Cali cartels splintered Hydra-like into more numerous and less verticalised organisations. The old, clunky hierarchies became looser, more resilient and increasingly decentralised networks. With the old cartels out of the way, a loose confederation of mid-level traffickers and paramilitary bosses in Colombia soon took charge of the restructured business, becoming (for a while, at least) the new kings of cocaine.Footnote 30

Meanwhile, on the production side of the business, although US-backed eradication campaigns in Peru ‘successfully’ decimated the country's coca plantations, they quickly popped up copiously in the jungles of Colombia, a coca boom that more than made up for its neighbour's lost acreage. These displacements constitute such a predictable pattern of failure that advocates for drug policy reform even have a name for it: the ‘balloon effect’. Squeeze the drug trade in one place, and it simply bulges out somewhere else. A similar effect occurred with the ‘success’ of interdiction efforts: as the United States intercepted shipments and clamped down on smuggling routes across the Caribbean basin, they ballooned in Mexico and, eventually, in Central America.Footnote 31

The militarisation of the drug war reached new heights in the 2000s when Washington's anti-drug and counterinsurgency programme known as Plan Colombia sprang into action. The aid package not only reinforced the twin pillars of eradication and interdiction, it also backed a frontal assault on Colombia's rebel groups. In doing so, Plan Colombia helped strengthen the rebels’ sworn enemies: localised paramilitary groups which had been managing the country's cocaine underworld for almost a decade.Footnote 32 It was in this period, too, that the Mexican cartels started taking greater control of transport and logistics – that is, the greater part of the cocaine commodity chain. As most of Colombia's paramilitaries demobilised from 2003 to 2006, the Mexicans consolidated their new-won position within these networks;Footnote 33 and as Mexico's cartels gained strength, President Felipe Calderón declared an all-out war, unleashing 45,000 troops against them across the country. With more than US$2.5 billion in US military aid, Mexico's drug war has resulted in unprecedented carnage: some 200,000 people killed and 32,000 disappeared since Calderón's declaration of war in 2006.Footnote 34

Throughout the first decade of the 2000s, the spill-over effects began seeping into Central America from two directions. Nothing about this spill-over was natural. With coca production booming and trafficking routes already moving toward the mid-section of the Americas, the US-backed crackdowns in Colombia and Mexico created a pincer movement that further sandwiched drug flows into Central America. Of course, the region was no stranger to the drug trade; cocaine had been playing an important role in Central American geopolitics for decades – from the Contra rebel groups in Nicaragua, to Manuel Noriega in Panama.Footnote 35 But the effects of the drug trade reached a whole new order of magnitude once the isthmus became the main transhipment corridor for US-bound cocaine in the 2000s. It was in these years that the media began warning that Guatemala was being Colombianised and on its way to becoming a full-fledged ‘narco-state’.Footnote 36

Without US policy as a key protagonist in the story, Colombianisation leaves the drug-fuelled violence and corruption currently affecting Central America completely unexplained. The reasons behind these phenomena are either left unquestioned; misattributed to blind market forces; or, worse still, chalked up to some innate cultural propensity toward graft and violence, as Olney implies by framing the region's gang problem as part of the so-called Clash of Civilisations.Footnote 37 Although Colombianisation seems premised on a geographical conception of drug trafficking, it obscures many crucial geographical connections and the reasons behind their movements across space. Indeed, the discourse disconnects spatial and social processes from each other to such an extent that their jointly produced outcomes – in this case, violence, disorder and corruption in Central America – appear inevitable, inexplicable and even natural.

Omission of Deeper Political-Economic Factors

Colombianisation also muddles the geography of drug trafficking by completely eliding the political-economic conditions that made Central America into such an amenable space for drug trafficking in the first place. Colombianisation implies the drug trade suddenly sprung out of South America and into Central America during the 2000s for almost no apparent reason other than logistical convenience. But the region's rise as a violent cocaine entrepôt was decades in the making; it was the product of a convergence of factors, including the legacies of Cold War militarism, the onset of neoliberalism, and ongoing forms of political instability. The US anti-drug efforts that began pushing traffickers into Central America in the 1990s coincided and became intertwined with profound political and economic transitions under way at the time.

Central America's civil wars, which were in their final throes, primed the region for the proliferation of trafficking networks and the war on drugs. The wars left Central America awash with arms: as many as 360,000 military-grade weapons were never handed over in El Salvador; and, somehow, after 36 years of fighting, the peace process in Guatemala turned up only 1,824 firearms.Footnote 38 Decades of war and US interventions left weak government institutions, decimated civil societies and bloated police and militaries. With the Cold War fading as a global threat paradigm, the securitisation of the war on drugs gave both the Pentagon and Latin American security apparatuses a new justification for stepping up rather than drawing down their activities in the hemisphere. As one US military commander cynically remarked during this transitional period, ‘It's the only war we've got.’Footnote 39 The momentum of militarisation and an upswing in criminal violence – the latter being a structural feature of most post-conflict transitions – meant Central America's hoped-for ‘peace dividend’ never materialised.Footnote 40

Central America's economic reality after the conflicts didn't help either. The post-war ‘transition to democracy’ turned out to be more of a transition to neoliberalism. Region-wide, the neoliberal policy package of privatisation, deregulation and austerity created even more lopsided economies. The healthy growth rates of the 1990s lined the pockets of elites, but they did almost nothing in terms of poverty reduction and they made inequality even worse. Today, more than half of Central Americans still live below the poverty line and a quarter of the population endures extreme poverty.Footnote 41 Neoliberalism and the later implementation of the US–Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) have been especially vicious for rural areas, where rates of extreme poverty have become more than twice as high as they are in the region's cities.Footnote 42

Mass rural poverty and the dwindling fortunes of agrarian elites both contributed to Central America's rise as a waypoint for cocaine. Agrarian elites did not fare as well as their urban counterparts under neoliberalisation. Rural oligarchies were still reeling from the insurgencies when the reduction in tariffs and subsidies further jeopardised their fortunes. The incoming narcos became a welcome source of cash and influence for these embattled rural elites. As the narcos snapped up huge tracts of land for laundering and investing their drug profits, they fused with the old-guard landowners into a single hybrid class: a ‘narco-bourgeoisie’.Footnote 43 The narco-bourgeoisie have turned huge swathes of Central America's most depressed rural areas into beachheads, corridors and landing strips for moving their illicit product northward.

Impoverished campesino communities across the region are in dire straits. A struggling rural economy means the long-standing problem of land maldistribution is now accompanied by a total lack of local job opportunities. With grim prospects, campesinos have become the hired-hands and social infrastructure on which trafficking networks depend.Footnote 44 For the rural poor, the drug trade is one of the few alternatives to leaving for the city or, further still, al norte. Like any global business, the drug industry gravitates toward spaces with favourable social and political-economic conditions. If apparel manufacturers can find cheap sources of labour and ideal regulatory environments, then so can drug traffickers. All this at a time when CAFTA's trade liberalisation and the associated construction of infrastructure (ports, highways and the like) has facilitated the free flow of goods, legal and illegal, throughout the region.Footnote 45 But whereas legal corporations might shy away from places afflicted by political instability, narco-syndicates thrive on it.

The 2009 coup in Honduras is a case in point: it secured Central America's position as the drug war's latest ground zero. At a moment when cocaine flows were already pouring into the region, the coup empowered the most corrupt sectors of the country's establishment. Together, political, military and economic elites opened the floodgates for traffickers and helped turn Honduras into what was, for a time, probably the world's busiest cocaine hub. Three years after the coup, the US State Department reported, ‘79 percent of all cocaine smuggling flights departing South America first land in Honduras.’Footnote 46

Through its fetishised simplification of the way drug trafficking ‘moves’, Colombianisation discursively glosses over the political and economic preconditions that helped transform Central America into a viable space for cocaine transhipment. Violence, poverty, inequality and corruption did not just precede the flood of drugs into Central America, they were its conditions of possibility. The presence of drug-trafficking networks has certainly made violence and state corruption worse, but they are still also fundamentally tied to the legacies of Cold War militarism, neoliberalisation and political instability. Moreover, Colombianisation suggests that the explosion of drug-related violence and corruption are aberrations when they have, in fact, become integral structural features of Latin America's actually existing democracies and free market economies.Footnote 47 Within the context of the war on drugs, neoliberalisation and securitisation have gone hand in hand.

Indeed, as the next section shows, the drug war is a socially embedded system in which economic and geopolitical interests are heavily (and quite literally) invested. Colombianisation's reductive errors in interpretation turn into tragic consequences when translated into policy. If Central America's woes are reduced to the problem of drug trafficking, then the securitised ‘solution’ is limited to standard anti-drug efforts – that is, more militarisation and mano dura (iron-fisted) crackdowns – rather than the deep social, political and economic reforms that the region so badly needs (and that would make a far more significant and lasting dent in the drug problem). It is the supposed ‘solutions’ enabled by Colombianisation that make it such a dangerous discourse.

What Does ‘Colombianisation’ Enable?

Colombianisation has major real-world consequences. For starters, it suggests the war on drugs must soldier on because trafficking is ‘beginning’ to spread. Never mind that the drug war is a demonstrable, repeated failure, even by its own metrics. The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) has meticulously documented the serial failures of the war on drugs for 40 years. Regardless, Colombianisation sustains a line of reasoning that the successful resolution of the drug war in one place (Colombia) must be followed by similar wars elsewhere, because, of course, new fronts against organised crime are opening up all the time. Central America is just the latest case of how, in the words of The Economist's naturalised metaphor of Colombianisation, ‘the rot spreads’.Footnote 48

The Colombian experience has a dual valency for securitisation within this discursive formation: it is not only a cautionary tale about how bad things can get, it is also increasingly held up by drug warriors as a model solution.Footnote 49 In this narrative, the violent military campaign that the South American country began in 2000 with billions of dollars in US aid pulled it back from the brink of becoming a ‘failed state’ overrun by guerrillas and drug traffickers. Plan Colombia supposedly helped put the country on a path toward peace and prosperity. Colombianisation justifies the further militarisation of the drug war in Central America based on dubious claims about Plan Colombia's supposed success. Moreover, this militarisation is dovetailing, as first occurred in Colombia, with the expansion of agroindustrial production in Central America. Rather than compartmentalising Colombia and Central America as bounded instances of comparable processes, we emphasise the concrete interrelationships and circulations that connect them.

Two, Three, Many Plan Colombias

As international media began using Colombianisation to identify Central America as the latest victim of drug-related violence, they were simultaneously touting the ‘Colombian Miracle’ by pointing to the country's improved security situation and its booming economy.Footnote 50 Prominent voices within the US military and foreign policy establishments began holding up Plan Colombia as a replicable success story. In fact, Washington's first attempt to export Plan Colombia was not to Central America or to Mexico, but to Afghanistan. In the 2000s, two US ambassadors to Bogota were reassigned to Kabul thanks to their track records overseeing Plan Colombia – a third was reposted to Islamabad.

In practice, Plan Colombia was less of a cohesive or stable plan than simply a framework for funnelling military aid to the country through Congress’ annual appropriations to the State Department and the Pentagon. In 2007, shortly after Mexican President Calderón launched his offensive against the cartels, he sought a comparable framework and cut a deal with the George Bush Jr. administration for US$2.5 billion in assistance that came to be known as the Mérida Initiative. Whereas Plan Colombia was mainly focused on drug-crop eradication and rural counterinsurgency, the Mérida Initiative – dubbed Plan Mexico by its critics – was more geared toward law enforcement and interdiction. Although they are distinct programmes with unique features, the Mérida Initiative was nonetheless inspired and justified by the trumped-up success of its Colombian counterpart.Footnote 51 Central America also joined the Mérida deal. From 2008 to 2015, under what is now known as the Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), the region received US$1.2 billion in US anti-drug aid. The influx of security assistance has pushed local militaries toward domestic policing and militarised the region's police forces, a process further encouraged by draconian mano dura anti-crime laws.Footnote 52

Despite the securitisation of Central America's drug-related problems, they have just got worse. The surge in drug trafficking, violence and corruption in recent years has sparked renewed calls for a more thorough US-backed militarisation of the region along the lines of Plan Colombia. A headline from the hawks at the National Interest, for instance, blared, ‘U.S. Needs a “Plan Colombia” for Central America.’Footnote 53 In Foreign Policy, James Stavridis, a retired four-star US Navy admiral, wrote, ‘We know how to end drug violence in Central America: stick to what worked in Colombia.’Footnote 54 US support undeniably helped the Colombian military crush the country's leftist insurgencies. However, it is also undeniable that Washington's support for one of Latin America's most abusive security forces – and, by extension, its murderous paramilitary proxies – contributed to the conflict's horrifying human toll: more than 250,000 civilians dead and almost 6 million displaced.

Moreover, contrary to claims about ‘what worked in Colombia’ and despite spending billions of dollars and leaving hundreds of thousands of victims, Plan Colombia was an unmitigated failure at curtailing the drug trade. The top priority of its stated mission was to cut drug production by half. But over the course of Plan Colombia's life span (2000–15), coca and cocaine production in the country ultimately increased, hitting record levels by 2016.Footnote 55 Although the government's peace accord with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) was a historic achievement worth celebrating, the country is still wracked by drug-related violence – in fact, high-intensity conflict in some places – and it still produces about 90 per cent of the world's cocaine.Footnote 56 As a discourse that proposes both a diagnosis and prescription, Colombianisation speaks against itself with a patent contradiction: while claiming the scourge of drug trafficking is migrating from Colombia to Central America, it proposes the problem should and could be solved with the same militarised strategy that, in fact, failed abysmally in Colombia. In this way, Colombianisation helps the drug war proceed with its militarised business-as-usual, regardless of the destruction left in its wake.

A Military-Agroindustrial Complex: The Real Colombianisation?

Amid the explosion of drug trafficking throughout Central America, Plan Colombia's so-called success story provides a powerful discursive architecture for the convergence of a broader set of geopolitical and economic interests amidst the securitisation of the isthmus. Specifically, the drug war has facilitated the entrenchment of a mode of militarised agroindustrial development that Colombia had arguably perfected, and which it has benefitted from chaperoning into Central America. In this final section, we detail how Colombia has helped established this violent model of agrarian development in three ways: by training regional militaries, through its involvement in the expansion of the local oil palm industry, and via its role in the financialisation of Central America's agricultural sector.

Through this constellation of interests and buttressed by the securitisation of the drug war, Central America has become the site of a growing ‘military-agroindustrial complex’, in which novel forms of US-backed militarisation are operating in conjunction with land-grabbing agribusiness developments. The resemblance of this process to Colombia's prior experience with collusion between agribusinesses and illicit actors in the violent dispossession of campesino families is not coincidental. The Colombian experience is in many ways the aspirational referent for the ensemble of strategies constituting this burgeoning military-agroindustrial complex. In fact, the Colombian military and Colombian capital are at the vanguard of this process.

Colombian Military Involvement in Central America

As in Colombia, US military intervention in the region is playing a role, but it is now routed through new geographical coordinates. Whereas Plan Colombia and CARSI provided US military assistance and expertise from North to South, Central America's militarisation is also happening through ‘South–South’ and ‘triangular’ forms of military cooperation via Colombia.Footnote 57 The trend began in earnest in 2010 when Colombia started making a concerted push toward capitalising on its decade-long experience with US-backed militarisation by exporting its know-how abroad. Between 2010 and 2015, for instance, Colombia provided training to almost 30,000 police and military personnel from around the world, instructing them in things like drug interdiction, intelligence gathering, special operations, and much more. But the overwhelming bulk of these trainees were from just four countries. Ecuadoreans, Guatemalans, Hondurans and Mexicans accounted for anywhere between 45 and 85 per cent of all trainees in each annual cohort.Footnote 58

The Pentagon has looked on approvingly, pointing out that Plan Colombia helped turn the South American country into a ‘net exporter’ of security. The top-ranking officer of the US Southern Command (SouthCom) explained the trend at a US congressional hearing:

With Colombia increasingly taking on the role of security exporter, we are facilitating the deployment of Colombian-led training teams and subject matter experts and attendance of Central American personnel to law enforcement and military academies in Colombia as part of the U.S.-Colombia Action Plan on Regional Security Cooperation. This is a clear example of a sizeable return on our relatively modest investment and sustained engagement.Footnote 59

The Action Plan he mentioned is a programme run out of the US Embassy in Bogota that coordinates the anti-drug efforts of Central American and Caribbean security forces under the joint leadership of the US and Colombian militaries. Summing up this triangular relationship, a US State Department official noted, ‘We used to ask, “What can the United States do for Colombia?” Now it is “what can we do with Colombia”.’Footnote 60

For the Colombian government, cooperation with foreign security forces fulfils several strategic objectives at once. To begin with, it helps improve Colombia's international reputation and increases its clout in Latin American and global affairs. It also gives its bloated and idle military a new-found purpose and justification for resources amid the uncertainties of the ‘post-conflict’ transition. Additionally, as Arlene Tickner has convincingly shown, Colombia's security cooperation with its neighbours is also a way of aligning itself more closely with the United States.Footnote 61 Although Colombia finances and provides a good deal of this security assistance on its own through direct, bilateral or ‘South–South’ relationships, the rest of it is ‘triangular’, meaning that Washington sponsors, funds and vets the assistance that Colombia provides to the security forces of third countries.

For the Pentagon, the militarisation of Central America by proxy is an attractive option for several reasons. Most broadly, it aligns with the US military's attempt to give its global interventions a lighter footprint in the wake of the disasters in Afghanistan and Iraq; and Washington has a long track record of using Latin America as a laboratory for its global security strategies.Footnote 62 In the context of Latin America, where US involvement is usually met with warranted suspicion and opposition, the tactics of ‘training the trainers’ and militarisation-once-removed are particularly well suited to giving its interventions a lower profile. With calls in Washington for US disinvestment from the drug war, outsourcing operations to ‘foreign partners’ makes both political and fiscal sense. Triangulating the militarisation of Central America and Mexico via Colombia also helps bypass the human rights conditionalities attached to direct US military assistance. Washington can absolve itself of the human rights abuses and the questionable legalities that typically come with securitisation. The Pentagon insists that all the police and military units in Central America that receive US-funded training from Colombia are vetted to ensure the protection of human rights. But these assurances ring hollow considering that the abuses of security forces in Central America are rarely documented – much less prosecuted.Footnote 63

On the question of human rights, the commander of SouthCom in 2014 made revealing comments before Congress about the triangulation of military aid to Central America through Colombia:

[Central American countries are] where Colombia was in the 1990s, they are just a few inches away from falling off the cliff … The beauty of having a Colombia … [is that] when we ask them to go somewhere else and train the Mexicans, the Hondurans, the Guatemalans, the Panamanians, they will do it almost without asking, and they will do it on their own … But that is why it is important for them to go. Because, I am, at least on the military side, I am restricted from working with so many of these countries because of limitations that are really based on past sins.Footnote 64

His statement is not only a clear example of the ongoing power of the Colombianisation discourse in Central America's militarisation (the region is ‘where Colombia was in the 1990s’), it also corroborates critics’ suspicions that triangulation is the Pentagon's workaround for backing abusive military and police forces in Central America with impunity.

Human rights concerns raise an even more basic question about whether Colombia is such a desirable ‘model’ in the first place. According to Colombia's National Commission on Historical Memory, the country's security forces and their paramilitary proxies were responsible for more than two-thirds of all the civilian massacres committed during the armed conflict, which claimed more than 262,000 lives – about 2,400 of these victims were extrajudicial executions by police and military.Footnote 65 Setting aside these abuses, even the so-called best practices Colombia is now exporting to Central America were forged in a context of a brutal war with active insurgencies. In Central America, these same tactics turn law enforcement and policing into warfare, further escalating what is already an unbearably violent situation. The militarisation of the region is also further blurring the line between military and civilian affairs, a process linked to the growth of privatised security and extra-legal violence.Footnote 66 Across the globe, the Colombian military has successfully hawked its expertise in counterinsurgency and post-conflict management by whitewashing its human rights record and actively branding itself as a humanitarian force.Footnote 67 However, Colombia's conflict continues to simmer: the military is still fighting a few holdout rebel groups, including remnants of the FARC, and hostile drug-trafficking militias still control large swathes of the nation. Apparently, peace matters little to measures of Plan Colombia's success. But that hasn't stopped the security forces from organising international conferences in which military brass from around the world visit Colombia to learn about the ‘success’ of the country's counterinsurgency and anti-drug operations.

Militarising the Agroindustrial Frontier

Central America obviously has its own history of death squads and paramilitaries, but many parts of the region – especially in Guatemala and Honduras – are now facing patterns reminiscent of Colombia's more recent experience with drug-funded paramilitaries.Footnote 68 In both cases, the fusion of drug-traffickers and landowners has fuelled the mass dispossession of campesino farmers.Footnote 69 By some accounts, the connections between Central and South America on this front are physically direct. In 2009, for example, media reports from Honduras made unverified claims that local landowners were importing members of Colombia's recently demobilised paramilitary groups as hired guns for their burgeoning cattle and oil palm operations.Footnote 70 Regardless of the presence of foreign mercenaries, the current patterns of violence against land rights activists and environmentalists in many parts of rural Central America – as with Berta Cáceres in Honduras and Rigoberto Lima Choc in Guatemala among many others – have striking parallels with those found in Colombia.Footnote 71 In both places, the violence around land and agribusiness comes courtesy of ‘public–private partnerships’ between the armed thugs of narco-landowners and members of the state security forces, bringing the drug war full circle with the military-agroindustrial complex. US aid to Central America may be framed in terms of ‘citizen security’, but its objectives in practice are still largely focused on protecting private property and extending military control into – that is, securitising – agricultural areas.

The conditions surrounding Colombia's oil palm boom exemplify the violent public–private partnership driving campesinos off their lands for agribusiness development.Footnote 72 From 2002 to 2010, the amount of land in Colombia planted with oil palms doubled in area, turning it into the largest producer of palm oil in Latin America and the fifth-largest in the world.Footnote 73 During this same period, campesino dispossession reached record levels in the country.Footnote 74 Relatedly, these were also the peak years of Plan Colombia, which helped the paramilitary movement metastasize across the country by shoring up its state-based sponsors. Plan Colombia, through its agricultural assistance programmes, also bankrolled a sizeable portion of the oil palm boom.Footnote 75 Recent studies have found a significant geographical correlation between paramilitary-led dispossession, land concentration and oil palm plantations.Footnote 76 Colombian courts, meanwhile, have corroborated these links, convicting more than a dozen plantation owners for colluding with paramilitaries in stealing campesino lands and for using their investments in oil palm to launder drug money. The authorities are still investigating an additional 25 oil palm companies for the same crimes.Footnote 77 Oil palm plantations are furthermore notoriously destructive enterprises for tropical lands, forests and waterways.

The track record of the Colombian oil palm sector, as an exemplar of the military-agroindustrial complex, matters for the purposes of this commentary because not only is Colombia sharing its military knowledge with Central America, it has also begun exporting its agroindustrial expertise. Through international meetings, site visits and personnel exchanges, Colombia's National Federation of Oil Palm Growers (Fedepalma), a private-sector organisation, has provided extensive advice and technical assistance to the booming oil palm industries of Guatemala and Honduras.Footnote 78 Plan Puebla–Panamá (PPP), later renamed Plan Mesoamérica, has also become a platform for the oil palm industry's transnational integration. Through its observer status in the PPP, Colombia encourages its private firms to sell palm oil processing equipment to flex-fuel production projects in Central America funded by the Inter-American Development Bank.Footnote 79 In 2008, also under the auspices of the PPP, Colombia's Ministry of Agriculture agreed to build three biodiesel production plants in Central America; it awarded the construction contract for the plants to a Colombian oil palm consortium.Footnote 80

This is not to say Colombia or Fedepalma are corrupting their counterparts in Central America; regional oil palm companies already had a well-established record of land-grabbing against campesinos and indigenous groups long before Fedepalma's involvement. Primitive accumulation in spaces like Guatemala's Petén or the Bajo Aguán of Honduras is certainly not new.Footnote 81 What is new, however, is the way narco-capital and illicit actors are fuelling land dispossession and environmental destruction at unprecedented rates.Footnote 82 After cattle ranching, oil palm appears to be the industry of choice for the landed narco-bourgeoisie of Central America.

Our point is not that Colombia, the Pentagon, traffickers or Fedepalma are executing a preconceived conspiratorial plan in establishing this elaborate military-agroindustrial complex; we are not alleging they are following a set blueprint from place to place.Footnote 83 Far from it, our argument is that narcotrafficking and the US-sponsored war on drugs have produced a convergence of political-economic and geopolitical forces that are playing out in similar ways in different places: not because these forces are migrating from one place to the another, but rather – and this is our key point – because they are all part of the same system.

Rural Financialisation

Trends in the oil palm sector form part of a larger and simultaneous flood of capital surging into Central America from Colombia. Between 2006 and 2013, foreign direct investment (FDI) from Colombia to Central America grew by an average rate of 54 per cent.Footnote 84 The trend began in the 2000s when the consumer and corporate-lending arms of many Colombian banks began following their clients into Central America. As US- and European-based banks began pulling out of the region in response to the 2008 financial crisis, Colombian banks staged what one report described as a full-fledged ‘shopping spree’ of the foreign banks’ assets in the region.Footnote 85 Many of the purchased Central American banks had been founded to support the agricultural sector, including Grupo Agromercantil in Guatemala and Banco Agrícola in El Salvador. In 2010, Colombia's Grupo Aval purchased BAC International, the largest financial institution in Central America. In 2012, when HSBC was fined in the United States for laundering the profits of Mexican cartels and other criminal groups, its Central American holdings were bought up by Bancolombia and Davivienda, both Colombian. Colombian firms now dominate Central America's banking sector.Footnote 86

These Colombian-owned financial institutions have been bankrolling the regional expansion of export agriculture, especially oil palm. Central American governments have also followed Colombia's lead in fostering their oil palm industries through tax breaks, soft loans and foreign assistance programmes. Through this financialisation of the agricultural sector and favourable public policies, palm oil plantations have exploded across Central America. With more than 370,000 hectares already in production, Central America has one of the fastest-growing oil palm industries in the world.Footnote 87 The growth in agribusiness development has been accompanied by a region-wide boom in infrastructure construction – much of it being built by Colombian companies.

After finance and manufacturing, extractive industries (mining and hydrocarbons) and infrastructure (electricity, water, gas and transportation) are the largest sources of FDI from Colombia.Footnote 88 Indeed, in conjunction with the Colombian-led financialisation of the rural sector in Central America came the increased penetration of powerful Colombian companies: in 2010, EPM, a state-owned utilities conglomerate based in Medellín, expanded its operations into Central America, buying up local utilities while making huge investments in power plants and hydroelectric projects; Colombia's state-owned oil company, Ecopetrol, also began making inroads into the region; and, in 2009, the Colombian airline Avianca announced it was absorbing TACA, the Central American carrier. The entry of these companies into Central America occurred at the same time that Colombia became directly engaged in the region's anti-drug efforts. Colombia's ongoing military intervention in Central America and its role in processes of securitisation must be understood in relation to how much the country suddenly has at stake in the region.

Conclusion

We have defined Colombianisation as a securitising discourse that draws simplistic and superficial parallels between Colombia's history of drug-related violence and corruption and Central America's current experiences with these problems. By focusing on the most sensationalist aspects of the drug trade, the discourse presents the movement of drug trafficking and its damaging collateral effects as a series of contagious pathological traits that move from place to place. As a set of securitising moves, Colombianisation operates in two mutually reinforcing and yet ultimately contradictory ways: Colombia is both a cautionary tale of a ‘worst case’ scenario for Central America as well as a model solution. Colombianisation proposes both a diagnosis and a (militarised) cure.

The geographical imaginaries of Colombianisation are not a total fiction. As part of the drug war's socially constructed regime of truth, the discourse rests on some obvious and incontrovertible facts. The geographical locus of drug trafficking has indeed shifted; Colombia and Central America do have longstanding historical and geographical ties with regard to drug trafficking and the drug war. But what ultimately makes Colombianisation such a slippery and insidious discourse is the way it suggests geographical relationships while at the same time misconstruing them in ways that encourage unquestioned public devotion to disastrous and ineffective policies.

We have identified three ways in which Colombianisation's spatial fetishism mischaracterises the actual geographies through which drug trafficking, the drug war, and their attendant economies of violence operate. First, it denies the drug trade's relational geographies; second, and perhaps most egregiously, it entirely leaves out the role of the United States and thus naturalises the drug war's foreseeable failures; third, it ignores all the political-economic conditions that help drug-trafficking networks take root. In short, the links between Colombia and Central America are not a series of disconnected and unfortunate coincidences; they are part of a system fuelled by a global prohibition regime that serves powerful interests. By pointing out some of the overlooked connections and circulations between Colombia and Central America, we have highlighted a clear set of geopolitical and economic interests well served by the Colombianisation discourse: the military-agroindustrial complex.

Colombianisation – as a dangerous discursive formation that enables this military-agroindustrial nexus – is both a driver and a result of a consistent pattern seen in many rural areas of Central America: the joint workings of the drug trade and the drug war tend to open up these spaces to more intensive kinds of capitalist development and state territorialisation.Footnote 89 The ultimate beneficiaries of the drug trade are not the world-famous capos who colour our sensationalist TV shows. The real winners are the supposedly legitimate banks, agribusinesses, large corporations, landowners and military forces at the helm of the military-agroindustrial complex. Flush with money provided by a booming banking sector, agribusinesses and landowners continue leveraging their assets – both violent and financial – toward the expansion of industrial agriculture and the accumulation of more and more land. In other words, the winners are los mismos de siempre, the rich and powerful. The drug war in general and Colombianisation in particular have afforded them new opportunities through which to maintain their power and profits.

Our account of the nexus between militarisation, financialisation and agribusiness development makes clear that the drug trade and the drug war do not take place in a vacuum; they have become integral parts of ostensibly ‘legal’ regimes of accumulation and rule in Latin America. Although the Colombianisation of Central America implies political disarray and chaos, the state-led projects enabled by these discourses are extremely well organised and inseparable from broader efforts aimed at expanding global trade, making spaces governable and attracting capital.

Critics might accuse us of over-analysing and reading too much into Colombianisation; they might claim we are overstating the power and consequences of this discourse. But in every section of this commentary, from the drug war's balloon effects to the multiple afterlives of Plan Colombia, we have consistently shown the tight linkages between discourse and practice. Presidents, defence ministers, diplomats, high-ranking military officers, security strategists and international military agreements – along with scholars and the press – are just some of the more prominent vectors of Colombianisation's contribution to the drug war's securitisation and militarisation.

Colombianisation enables certain kinds of practices and courses of action while disabling others. It is through these subtle and mutual workings of discourse, power and practice that an indefensible war on drugs maintains its status as a common-sense ‘solution’. Colombianisation thus forms part of the broader ideological armature of the drug war that makes it so resistant to evidence-based policy-making and reform. In this commentary, we have tried to poke some holes through one piece of that armour.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) under funding received from the National Science Foundation (DBI-1052875). We thank the members of the Landscapes in Transition for Central America research project (supported by SESYNC) for feedback during the early conceptualisation of the commentary.