For about two decades historians have been eager to find out how peasants participated in the formation of Latin American nation-states. In some cases, like Mexico, scholars have shown that the peasantry was quite influential in the establishment of the nation-state after the independence struggles, while other scholars have argued that elsewhere, as in Peru, peasants – the vast majority of them defined as belonging to Andean indigenous communities – were excluded by a creole-dominated state that could not countenance the active participation of what the elites considered a socially and racially inferior group.Footnote 1 In the Andes in general it is assumed that indigenous peoples were not accepted as full citizens in the nation-state, but as subservient beings whose political, social and economic development retarded the building of new, modern states.

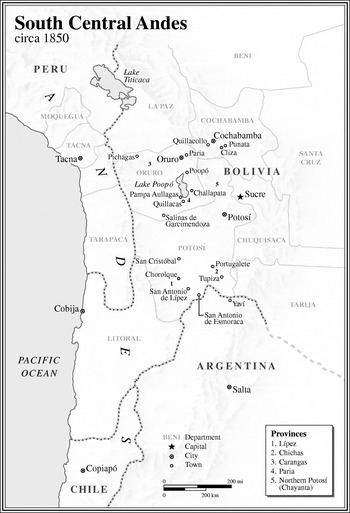

Map 1.

This new approach integrating subalterns into our understanding of the formation of the nation-state in Latin America has been very influential, and has inspired a generation of young scholars to examine whether and how non-elites influenced the nation-forming process. As a result, under the influence of the subaltern studies model pioneered in India and Antonio Gramsci's ideas about hegemony, many studies have shown how peasants, women, Afro-descendants, indigenous peoples and even slaves have affected the discourse on nation building and thus the political structures that emerged after independence.Footnote 2 Despite the different groups that this literature has encompassed, it has focused mainly on political issues and power, without placing much emphasis on other factors such as the economic integration of non-elites and the effects that this had on social and political incorporation.

The Bolivian case is illuminating on the topic of Indians and nation-state formation. Before the explosion of works in the United States on peasant participation, scholars of Bolivia had already discussed the integration of indigenous communities into the republic. Unlike the ‘new political’ approach discussed above, the Bolivian debate involved both political and economic issues. Tristan Platt posited an influential model of Indian – state relations in the Andes, in which highland indigenous communities interacted with the state on the basis of an implicit ‘reciprocal pact’. His idea had important fiscal and economic dimensions. The communities provided services and tribute to the state, in return for which they expected the state to protect their lands. Significantly, Platt discovered this notion in northern Potosí, where indigenous communities remained relatively untouched by hacienda expansion and had a strong agrarian base, planting wheat and exporting it to other regions within Bolivia.Footnote 3 He asserted that the Indians of northern Potosí were in favour of a protectionist regime because it protected wheat farming; when the Bolivian state opened up to free trade, imports of flour from Chile destroyed the flourishing wheat agriculture of the region. Moreover, the circulation of a weak and adulterated coinage, the peso feble, worked to the advantage of these Indians, since it kept out imports within Bolivia. The northern Potosí community members received pesos febles in payment for their wheat and paid their tribute with them as well.Footnote 4

Marta Irurozqui examined these dynamics, though from the perspective of the development of democratic culture, a difficult concept to manage for the nineteenth century.Footnote 5 Irurozqui's emphasis on rebellions as a means of fighting for rights within the republican context received further elaboration in her analysis of the 1899 Aymara rebellion, in which she claimed that the Bolivian elites refused to consider the Indians full citizens because they belonged to corporate communities and thus could not act as full citizens who were free of corporate influence.Footnote 6 Part of the problem with Indians was economic, in that their status as community members tied them to communal properties, preventing them from acting independently. Full citizenship, according to the concepts of liberal citizenship cited by Irurozqui, implied an economic independence that Indians presumably did not have. This distinction, according to Rossana Barragán, came from the difference that emerged in the French Revolution between ‘passive’ and ‘active’ citizens.Footnote 7

The indigenous population of Bolivia was important in the nineteenth century (as it is in the twenty-first) and is vital for understanding the construction of the nation-state. According to José María Dalence, the best statistical source for the nineteenth century, there were almost 1.4 million inhabitants in the country in 1846, of whom 659,398 were whites and 701,538 were Indians. Most of the Indians were concentrated in the economically most vibrant area of the country, in the high Andes and altiplano of the La Paz, Oruro, Litoral and Potosí departments. In this region, Indians outnumbered whites about three to one, or 550,292 to 183,309. In the altiplano department of Oruro, where mining, commerce, herding and, to a lesser extent, agriculture were the main economic activities, there were ten Indians for every white person.Footnote 8 The Indians in the Andes were largely merchants and peasants, living in communities organised in classic Andean fashion in ayllus, kinship-based organisations that stemmed from the pre-Columbian period but had been heavily modified by the long colonial regime.

Some Indians lived on haciendas, which had been carved out from the Indian communities during the colonial period. Until the late nineteenth century, however, haciendas were less common in the core Andean departments on the altiplano than in the valleys; they were most numerous in the valley regions of Cochabamba, Chuquisaca and Tarija. In turn, the vast far eastern departments of Santa Cruz and Beni (the latter created from the former in 1842) were isolated subtropical frontier regions with a sparse white population (less than 50,000), over which the Bolivian state had only marginal control. The indigenous population there, other than on the former Jesuit and Franciscan missions, was largely unconquered.Footnote 9 In other words, the indigenous population in the Andean highlands participated within the nation-state as part of peasant communities in ways that the sparser indigenous population in the valleys and the eastern frontier regions did not. For this reason, this essay concentrates on the Andean Indians and in particular on community members in the Oruro region of the altiplano. In this region indigenous community members were especially active as transporters of goods, herders, merchants and agriculturalists. Although perhaps not typical of the country as a whole, the extensive participation of community members in trade was a pattern that was common, especially on the altiplano. The altiplano had the heaviest concentration of indigenous communities in Bolivia (and the majority of the indigenous population). Since pre-Columbian times the people of this region had specialised in transport, given the wide, open spaces that eased communication and the excellent conditions for the raising of llamas for hauling.

Indigenous Trade and Perceptions of the Nation-State

Adding economic interests to the political equation is essential for understanding the behaviour of indigenous people (and other subalterns) in the construction of the nation-state in nineteenth-century Latin America. In the case of Bolivia, Platt was correct with regard to northern Potosí in his appraisal of the reciprocal pact and the importance of the communities' commercialisation of wheat to the mining and urban centres, but for other regions (and, I would argue, for the majority of the Indian communities in Bolivia) the situation was quite different.

The reasons for this are twofold. Firstly, many indigenous communities in the Bolivian highlands, where the vast majority of Andean peasants lived, participated in trade networks that took them beyond the formal boundaries of the Bolivian state. Secondly, agriculture was an important part of the Indian household economy, but it was often not the most important one. On the Bolivian altiplano and further south, in the mining districts and marginal lands of Lípez, Carangas, Paria and Chichas, commerce and the transportation of minerals were as important as agriculture in sustaining Indian households, possibly even more so.Footnote 10 While it was in the interests of the Indians to have the peso feble maintain its dominance beyond the Bolivian borders, their commercial connections beyond the nation-state gave them little incentive to play on their role as Bolivian citizens rather than Indians. This was the case because the utilisation of internal networks within indigenous communities made possible extraordinary commercial activity (and prosperity) until the 1860s. Not all Indians in the Oruro area participated in these networks, but it was one of the major revenue-producing activities for community members. Many of the commercial activities in which community members participated were related to selling goods made in the neighbouring states (rather than European imports). The indigenous communities thus continued to recreate, on a smaller scale, what Carlos Sempat Assadourian has called the ‘Andean economic space’, centred, in the colonial period, on supplying goods to Potosí. As Antonio Mitre and others, including the present author, have documented, this regional economic activity continued well into the nineteenth century.Footnote 11 In this sense, highland Indian community members were simply taking advantage of the economic opportunities that existed for them during that period. Other sectors of society also took advantage of the Bolivian state's lack of control of the domestic market, especially import-export merchants and silver miners. Many of these groups had ties to the outside and some undermined the Bolivian nation-state in a fiscal sense by profiting from extensive smuggling operations.Footnote 12 As we shall see, this involved the altiplano indigenous communities as well.

The highland Indian communities were very active in commerce with the world outside Bolivia, as importers and exporters, transporters of most trade goods, and smugglers. Most indigenous trade outside national boundaries involved goods produced in regions close to Bolivia's borders, known as productos de la tierra or productos de estados limítrofes. In 1836, for example, Indians brought 468 tons of cotton in 879 trips from the valleys in Moquegua and Tacna on the Peruvian coast, to sell to wholesalers in the Cochabamba region (Quillacollo, Punata, the city of Cochabamba, Tarata and Cliza).Footnote 13 It is highly likely that the amount of cotton that community members brought up from the coast was even greater, since the customs administrator claimed that the ‘Indians Calacotos don't come by the customs house any more to take out their permits [guías] for their cottons and peppers, because of their malice they go directly to town [Paria]’.Footnote 14

During the nineteenth century, Indians, for the most part from the surrounding communities, were also the transporters of minerals from the mines to the mills. The probate records of the tribute-paying Indians consistently show the number of llamas, mules and burros they owned, as well as the bags (costales) and ropes needed for transporting ore. For example, at his death Pedro Idalgo of Ayllu Culli in Salinas de Garcimendoza owned 110 llamas, 100 costales and 80 ropes ‘to bring down metal’.Footnote 15 This important activity tied community members to the miners in their districts and created a mutual dependence.

Although most of the merchandise traded by community members consisted of efectos del país or efectos de países limítrofes, indigenous intermediaries also engaged in the transport and smuggling of silver and gold out of the country. In most cases Indians were the transporters of the ore, and at times they also smuggled for their own profit. The smuggling took place through Argentina especially, but some ore also went to Peru. After all, community members knew the hidden trails across the mountains and were able to avoid customs officials. Pedro Idalgo, for example, also had in his possession 200 pesos in silver coins and ‘some marcos of silver in bars [piña plata]’, a product that a peasant such as Idalgo should not have possessed.Footnote 16 The possession of contraband silver went way back, as in the case of Agustín Nina, who in 1830 gave ‘some pesos’ to Cruz Gabriel to ‘acquire [rescatase] marcos of silver’ and go to Tarapacá (Peru).Footnote 17 Indeed, the region of Salinas de Garcimendoza, to the south-west of Poopó and Challapata, was a region known for smuggling its silver output to Peru and Argentina.

At times Indians were caught smuggling and had to pay the consequences. In 1843 Manuel Osnaya and Domingo Gua, community members of the Silpana and Olanique ayllus, along with five peons and a slave from Peru, were caught smuggling 103 marcos of silver and 69 marcos of tin close to the Pichagas customs post, which was located close to the Sajama trail to the coast of Peru. The government embargoed their 50 mules, three horses and 34 wine skins. Although the Indians claimed they were only transporting the metals for somebody else, whom they did not name, Gua was sent to jail for five years.Footnote 18 Indians suffered for transgressing the rules of the new nation-state when they smuggled goods. It is impossible to know whether Osnaya and Gua really were smugglers of metals that they themselves possessed or whether they truly were transporting them for others, but the state punished them in either case.

Mine owners and import-export merchants, such as Gregorio Pacheco from Tupiza, certainly hired Indian mule and llama drivers to take silver bars illegally out of the country. From the 1840s to the 1860s Pacheco, who would later become one of the country's most important silver miners and president of Bolivia (1884–88), was an import-export merchant who exchanged imported goods for silver ore. He had agents stationed in the important mining centres of Chichas, who purchased the silver for cash or in return for imported goods. Through his cousin in Salta, Argentina, he had the silver piñas (as well as a bit of gold, when it was available) smelted in Salta and then taken across the Andes to Copiapó in Chile, where his agents contracted coastal vessels to take the smuggled silver to Valparaíso, to trade for textiles and other imports. Pacheco used muleteers to take the ore from the various mining centres such as Portugalete, San Antonio and San Cristóbal to Tupiza, and then across the border to Salta. These muleteers were members of the Lípez and Chichas Indian communities, who specialised in crossing the formidable desert conditions of the high Andes. Pacheco himself had 2,424 and 1,805 marcos smuggled out in 1848 and 1849. By the 1860s Pacheco had lessened his risk by having others, presumably many of the same Indian llama drivers and muleteers, purchase the silver at the mines and smuggle the ore out of the country. He had his agents purchase it from the smugglers in the Argentine market town of Yavi, just across the border. In 1862 his agent there purchased 7,740 marcos of silver in this fashion.Footnote 19 Other merchants from Tupiza and other mining towns also engaged in this illicit traffic, but unfortunately it is impossible to know how successful Pacheco was in comparison to others. Nonetheless, the indigenous communities were undoubtedly active in transporting the ore across the border, thus gaining from the contraband trade.

Some Indians were also mine owners and, if the characterisation of the silver miners as free traders holds true for mestizos and whites, it must for Indians as well. Mine ownership by Indians was not uncontested, but it clearly did exist. For example, José Manuel Idalgo, an ayllu member from Carangas, worked as a partner with Don José Gregorio Iraola in the Socavón de Machacamarca close to Poopó, mining silver and tin. When three whites (the merchant Juan Cancio Lopes, the lawyer Dr Tomás Carpio, both of whom were from Oruro, and the miner Manuel Muños from Potosí) tried to take away the mine from Idalgo, ‘indicating that I do not have the faculty as tributary [Indian] to work mines’, he provided his account book to the judge. It showed that Idalgo supervised the work and had contracted up to eight labourers, paying expenses and purchasing coca leaf, liquor and chicha (corn beer) for them.Footnote 20 Another mine was owned by Jerónimo Mamani and Biviana Gomes. The couple, from the Quillacas ayllu, owned a silver mine in the Atacama region in Litoral province until their deaths in 1860. The goods they left, including 1,000 pesos in cash, almost 1,500 pesos in IOUs and a considerable amount of silver, was valued at over 5,000 pesos, without even taking into account the mining concession.Footnote 21

In 1855 the corregidor of Salinas de Garcimendoza estimated that more than 40,000 pesos worth of silver had been extracted from the province and transported to Argentina without passing through the mining bank in Oruro. The problem was endemic throughout the period. In 1860, the corregidor provided the figures of mine production to the Oruro mining bank, in order to calculate how much had actually been taken to the bank rather than smuggled out, though this measure had little effect. There were similar problems in Chichas, where state officials vainly tried to position their agents to cut off the silver smugglers.Footnote 22

In other words, many indigenous members of the altiplano communities engaged in economic activities, both legal and illegal, that placed their interests more in line with the free-trade silver miners and import-export merchants than with artisans, northern Potosí communities and other groups that favoured protectionism. Not all silver miners or merchants were free traders, but most were. Likewise, the Indians from Oruro maintained their interest in unregulated borders when they acted as smugglers of silver, transporters of smuggled silver and imported goods, and also silver miners. Their interests reflected the continuation of colonial networks that transcended the new republican political boundaries, but it was more than that. The extensive participation in these circuits was far greater than had occurred earlier, and the alliances between Indian commoners (not just the kurakas, or community headmen, as had been the case in the colonial period) and creole free-trade interests were new to the post-independence era.

Economic and Political Integration

Given the economic context of nineteenth-century Bolivia, how did these groups – and, in particular, the Andean communities – integrate themselves into the (admittedly weak) nation-state? One means, discussed by Tristan Platt, was through the payment of tribute and the implicit deal that put the state on the side of the communities in defending their land base.Footnote 23 This situation created what Platt called ‘a hybrid tributary-citizen status’, in which Indian communities were seen as an integral foundation of the state, since the latter depended on tribute for its fiscal survival.Footnote 24 In other words, the state was willing to accept community members, but only in a subordinate position, not as citizens who had equal rights under the law with mestizo or white citizens.

It is difficult to discern the extent to which indigenous community members felt part of the new nation-state anywhere in the Andes. Mark Thurner has asserted that community members in the department of Huaraz argued that they should be considered full citizens of the Peruvian nation-state as peruanos, people born and indigenous to the new republic. He found the use of the term republicanos, with a connotation that goes beyond the colonial term república de indios, although the exact sense is not clear. Thurner argued that while the Andean indigenous villagers wanted to be considered part of the nation, Peruvian authorities and the local mistis did not want to accept community members as full and equal citizens in Peru, as evidenced by the bloody repression of the Atusparia rebellion in the 1880s. However, Thurner's extremely slim documentary basis for the usage of these terms and the problem of distortion in terminology – what Andrés Guerrero, in the case of Ecuador, has called the ‘ventriloquism’ of the non-Indians who wrote the official documents – make his argument more hypothetical than it might appear at first glance.Footnote 25

In contrast, Charles Walker has claimed that the indigenous communities of Cuzco did not support the Peruvian caudillo, Agustín Gamarra, against Bolivian forces under the command of General Andrés de Santa Cruz in the crucial battle of Yanacocha (1835). According to Walker, this was not necessarily because of a lack of a sense of nationalism, but because the constant turnover of the caudillo-led state had shown communities that it was not in their best interests to die for a fickle cause. Despite this assertion, it is clear from Walker's account that the ties between creole caudillos, even ones as popular as Gamarra, and indigenous peasants were loose and probably not as close as in colonial times.Footnote 26

Citizenship in Bolivia was a complicated affair, and differed from the Peruvian case.Footnote 27 It is important to note that even Bolivian creoles did not always define themselves primarily as members of the new nation-states. Many members of the creole elites thought of themselves more in ethnic than national terms during much of the nineteenth century, as Tristan Platt argues.Footnote 28 Other Bolivian creoles also apparently had little sense of nationalism, as the almost complete lack of resistance to the Chilean invaders of the Atacama region in 1879–80, during the War of the Pacific, appears to demonstrate.Footnote 29 This contrasts with the legal terminology that the Bolivian state used in legal documents. In all customs documents and in judicial records, creoles or mestizos were identified as ciudadanos (citizens). Rather than signalling the self-identification of creoles, the use of this term was an artificial one that the state utilised to create a national identification that did not yet truly exist. The term ‘ciudadano’ also helped mask considerable ethnic diversity, since it included both those who considered themselves to be of European extraction and mestizos, whom the state, for fiscal, cultural, or racial reasons, did not consider Indians. In fact, in official correspondence officials used the term cholada or cholo (mestizo) freely, indicating that beneath the legal designations a racial hierarchy even within the category of ciudadanos was visible.Footnote 30

Only Indians were characterised by ethnic terms, but this had both racial and fiscal implications. In the legal documents they were called indígena, indígena contribuyente or indígena originario. These terms were important for the state, since they connoted a fiscal category: only Indians paid tribute. As mentioned above, tribute was the most important source of income for the Bolivian state for much of the nineteenth century.Footnote 31 It is important to note that, in items of documentation other than the formal legal ones, nobody was identified as ciudadano, although the terms for indigenous peoples, including indio and indiada, were used. The term ciudadano appears to have little resonance outside the official sphere, though racial classifications (combined with their fiscal meanings) remained evident to the inhabitants of nineteenth-century Bolivia.

It is hard to pin down what members of the indigenous highland communities thought of the new Andean nations, and whether they had a clear conception of what this meant or what their status should be. Tristan Platt argues that Andean Indians perhaps did not see independence as an important breaking point in their history.Footnote 32 Nonetheless, Simón Bolívar and the other independence leaders had a liberal project in mind for Andeans in which education and literacy would eventually bring about the integration of highland Indians as full members of national society. For this reason Bolívar abolished tribute in 1824 and divided up community lands, with caciques receiving twice as much land as regular community members.Footnote 33 This agrarian reform did not, however, endure, since the fiscal requirements of the Andean republics necessitated the reinstatement of Indian tribute (usually renamed) by governments desperate for revenue.Footnote 34

The nineteenth-century constitutions in Bolivia were ambivalent on this question and continued to provide special categories for Indians. According to Rossana Barragán, Indians in early republican legislation were considered pobres de solemnidad (poor by nature), who had to pay tribute but who should receive certain discounts for legal procedures.Footnote 35 In 1838 the administration of Andrés de Santa Cruz prohibited tribute-paying Indians from being impressed into the army because they ‘caused prejudice and ruin to the State’. This order was reiterated in 1843 and 1860, and not rescinded during the nineteenth century.Footnote 36 Moreover, community members in Bolivia continued to pay tribute to the national coffers until 1881, and into departmental treasuries well into the twentieth century.Footnote 37

It is important to move beyond mere rhetorical terms and examine concrete actions by the inhabitants of the new Latin American republics. Certain groups among the indigenous communities felt part of the nation-state and accepted that they occupied different positions in the nation-state from that of the ciudadanos. In the case of the Andes, within the highland indigenous communities the hierarchy of individuals had different ties and interactions with the state. For example, the kurakas who collected tribute payments and had frequent interactions with Bolivian officials had different ideas about the nation-state from regular community members.Footnote 38 Indians living in isolated regions where representatives of the state rarely appeared interacted with the state in different ways from those living along the major trade routes. The community members of the Bolivian altiplano who engaged in many mercantile activities, most notably those who lived in Oruro, had a more acute sense of the nation-state because of interactions with customs officials, though these interactions probably did little to endear them to the impositions of national authorities. These interactions, taken into account with their role as tribute payers, their exemptions from impressment into the regular army, and the state's formal role in preserving their land, all created a complex perception of the role of the state in their lives in which, I would argue, economic issues predominated.

Given the amorphous nature of the sense of nationalism in Bolivia during the nineteenth century, how can we analyse the sense of nationalism that existed among the highland indigenous communities without falling into useless generalisations or trying to find twentieth-century attitudes in the nineteenth century? In my view the answer lies in the economic activities of the highland communities and the way in which the state was made ‘visible’ through community structures. This did not mean that these Indians did not have a sense of national belonging, but I hypothesise that this sense of belonging was mediated through the community. The highland communities had complex hierarchies through which Indian families passed at different stages of their lives, and all of these, in one way or another, were linked to the relationship between the Bolivian state and the Indian community. To give an example, a series of lists from the 1840s containing the names of the individuals who served in various capacities in the canton of Challapata shows the links between community, Church and state.Footnote 39 Three postillones carried the mail and the official correspondence from the post office at Catarire. They were listed with their wives and each couple's fiador (bondsman), who guaranteed the couple's performance. There was also a list of the minor offices, each with a fiador, including the ‘segundo who helps with money [to pay] the total tribute [entero total] of both semesters’. The church had a list with two alfereces (sponsors of the festivals of the Virgin of Rosario and Saint Andrew) and two mayordomos of Saint Andrew and Saint Michael. There was also a list of three ‘Indians who will serve our adored nation this year as mitayos’, one of whom was a bachelor, as well as a widower who served as the llenero [?] of the parish priest, and a husband and wife who served ‘the state’. These men and women had been selected by the cabildo ‘in the presence of the whole community’ and were to ‘fulfil their duty without delay [and] in case that they fail to do so their bondsmen are co-responsible’.Footnote 40 According to the document, the whole community selected these individuals, based on its members' previous services, using a cargo system in which the officers worked their way up the ladder in prestige and also in the amounts they were required to contribute financially.Footnote 41

These obligations, despite their financial burdens, were often sought after by community members. In the case above, the lists of all the offices was entered into the court record because the corregidor, José María Salinas, replaced an alferez, Romualdo Poquechoque, with his own godson, Francisco Achu. Poquechoque complained to the court because he and his wife ‘according to our custom have been elected in three cabildos in the presence of the whole community of individuals by voice vote and without having another person who solicits this service’.Footnote 42 Salinas threw the community officials in jail when they supported Poquechoque rather than his godson. In the end the corregidor prevailed, because he claimed that Poquechoque had not yet passed through all the other minor offices and ‘because the individual involved himself in the accustomed drunken orgies [borracheras acostumbradas] that they called tinca and he, [though] justly elected, was careless about this abuse’.Footnote 43 The judge ordered the cacique to return the 200 pesos that Poquechoque had given to him as part of the obligations of his office and left Achu as the alferez.Footnote 44 Presumably Achu also had to pay this large amount for the privilege of becoming the sponsor of the town's religious festival.

Community members of the altiplano were able to make large monetary payments such as the one Poquechoque and Achu paid because they engaged in commerce that provided a sufficient surplus for them to do so. The community offices and their financial obligations provided for the festivities that bound the communities together as social organisms and also fortified the commercial ties that community members had amongst themselves. Festivals and trade went together, for festivals made the personal relations possible that led to common enterprises among community members. The judicial and notarial archives are full of probate records that show how the Indians used other community members as ‘subcontractors’ to transport and sell their merchandise. The festivals provided the largesse for the rest of the community and also showed that even the wealthiest (who tended to be the sponsors of the festivals as alfereces) provided services to the community. Andean communities in the nineteenth century were composed of households that varied considerably in wealth, but it is clear that the wealthiest felt an obligation (or were obligated) to contribute to those less well off than themselves.

The state officials most visible to the communities were undoubtedly the corregidores or subprefects (also called jefes politicos during the Linares administration between 1857 and 1861). They were selected by the departmental prefect and were the state's lynchpin in the countryside. As Robert Smale has pointed out with regard to the early twentieth century, the corregidor at times mobilised community members to act as a police force against poachers and other interlopers in the altiplano.Footnote 45 The communities played this role in the nineteenth century as well, when the corregidor of Salinas was ordered in 1855 to ‘without losing a single moment move all the indiada of the canton and the vecinos [whites and mestizos] with their arms to contain if necessary the invasion of the enemy, who should not be permitted by any means of setting foot onto our territory’.Footnote 46 In November 1860, the jefe político of Poopó used the Indians to make sure that the revolutionary José María Martínez, acting in support of Manuel Isidoro Belzu (president, 1848–55), was unable to enter his district from the valleys of Chuquisaca. The jefe politico claimed that he had ‘raised part of the indiada’ at Quillacas and Pampa Aullagas ‘with the objective of spreading them throughout the countryside’. He believed that if the revolutionaries dared to pass through those places ‘they would be taken prisoners for sure [because of] the patriotism and loyalty of this indiada’.Footnote 47 While Indians were generally not part of the military, at certain points they nevertheless played important roles in internal security for the state.

It is interesting that the jefe político used the term ‘patriotism’ to describe loyalty to a regime against an internal rebellion. Communications by the official suggest that the Indian community members of the Oruro region apparently supported the dictator José María Linares against his rival, Manuel Isidoro Belzu. It is impossible to know from the material that has survived how much the Indians were aware of or cared about the ideologies of either leader. One assumes that the Indians were willing to be mobilised by the jefe político because he had good connections with the community leaders and tried to alleviate the impositions of the state on the communities in his jurisdiction. Only a month before the rebellion the jefe político had complained to the prefect of Oruro about the difficulties the Indians had in supplying pack animals to the troops passing through the area.Footnote 48 The corregidor's action in aiding the communities probably counted for more in helping him mobilise the ayllus than the frequent pronouncements of the ever-changing presidents. However, state officials themselves defined ‘patriotism’ not as actions against foreigners, but as supporting the current administration. Indians could be patriots too, at least in this capacity.

Commerce, Tribute and Community Offices

The economic prosperity of the highland community members through trade and the transport of goods for the mines eventually brought about tensions between their tributary obligations, their ability to lead the communities, and their economic activities. Community leaders, such as kurakas, cobradores (tribute collectors), postillones and mitayos, did not just serve in their offices, but were usually responsible for paying for the privilege of these positions through sponsoring fiestas and other events and with their labour, and for making up any shortfalls. The cargo system that existed in the communities required increasing commitments as members moved up in the hierarchy of offices, as was usually the case.Footnote 49 While their mercantile enterprises brought in more than enough to pay tribute, the more active (and thus most prosperous) traders needed to be absent from their highland communities for extended periods of time. Since the offices required some personal resources, the community tended to pick the better-off members as their leaders. Most offices obliged them to remain near their homes to collect tribute, represent the community to state officials and resolve disputes between community members. Success in trade thus made the best members valuable as community members at the same time that these individuals had incentives to shirk the responsibilities of office.

In 1854, for example, Manuel Mamani of Ayllu Andamarca, which was near the town of Challapata, close to Oruro, tried to evade his duties as tribute collector. He was working as a merchant in the mining camp of Chorolque, in Chichas province (southern Potosí), when the community officials of Andamarca named him alcalde cobrador. The alcalde cobrador was responsible for collecting tribute, and therefore had to remain close to the community for most of the year. In the colonial period many community members would probably have jumped at the chance of collecting tribute, since the collection of the head tax, with the possibility of requiring greater payment from the tributarios than the state collected from them, made it a potentially lucrative enterprise.Footnote 50 But Mamani wanted none of this, because he was making more money trading in the mining camps. He asserted that he had already served three times as a tribute collector and twice as the head of the posta in Ancacato, in which he ‘had spent money and suffered losses in his commerce’.Footnote 51 Commerce, rather than collecting tribute, was for Indian community members the most lucrative activity in mid-nineteenth-century Bolivia.

The office of tribute collector was also a difficult job in some of the communities of the highlands, especially those ayllus that had fields of wheat and corn in the ecological archipelagos of the eastern valleys. Many, if not most, of the indigenous communities in the highlands maintained agricultural lands in the lower valleys where they could grow maize, coca, peppers and other foodstuffs that complemented their diets in the altiplano.Footnote 52 Some of the communities had transformed their lands in the valley into haciendas by reducing the Indians living there permanently to hacienda peons (arrenderos). These arrenderos had to pay rent that was collected by the community officials. In 1851 Agustín Carata, the indígena segundo cobrador of Ayllu Yucasa, in the vice-canton of Huari, complained to the judge in Poopó that the renters in the community's Hacienda San Juan de Orca had refused to pay their rents. San Juan de Orca was located in the subtropical valleys of Chuquisaca, to the south-west. According to the complaint, 19 arrenderos did not pay their rent in 1849 and another 13 refused to do so in 1850. These types of problems undoubtedly made these offices less popular, especially if other activities, such as commerce, were more lucrative. Indeed, the dispute came about in part because the previous tribute collector had refused to fulfil his duties when his turn had come up.Footnote 53

Thus despite the need for officers and the resulting benefits for the community as a whole, by the 1850s there are indications that some of the most prosperous and active members of the ayllus did not want to become village authorities. They preferred to remain outside the communities, ranging widely in their mercantile activities. There are also indications of substantial community differentiation in terms of wealth. This is clear in the valley agricultural lands, which the highland communities ran as haciendas, with their own peons, as was the case among the creoles. As noted already, the indígenas contribuyentes who owned mines likewise engaged workers who were paid in goods and wages, as in the mines owned by ciudadanos.

It is not clear how this differentiation and wealth affected the Indian community members' vision of themselves within the Bolivian state. Inter-ethnic relations probably intensified as wealthy indígenas lent money to ciudadanos, making them feel more equal, or perhaps even superior, to non-Indians.Footnote 54 Wealthy Indians used the services of the notary for their wills and their descendants resorted to the notaries for probate, in which the state provided certain services that also made the Indians more ‘visible’ to the state. The fact that they engaged with state agencies does not prove that Indians contributed to nation-state formation, however. They accepted the use of state institutions, particularly the national courts when undertaking litigation against other Indians and, most importantly, against non-Indians. They had the wherewithal to pay for lawyers and courts and so had a better chance of getting favourable verdicts. Indeed, there is no indication that the courts discriminated against Indians in their verdicts, at least in the legal papers that have survived.Footnote 55 It is likely that the use of courts by wealthy community members against those members who were less well off had the effect of solidifying the differences in economic status, since the wealthier members could afford to sustain a case longer than their poor counterparts. This is difficult to prove, however, given the paucity of systematic information on the effects of judgments.

Indigenous Economic Decline and the Rise of National Identity

By the end of the 1860s the economic picture had changed for the highland communities. Mariano Melgarejo, who became president of Bolivia in a coup in 1864, began a frontal assault on the prosperity of Andean community members through land legislation that claimed the state's rights over all community lands and tried to sell them at auction to the highest bidder.Footnote 56 We do not have much information on the effects of these laws in the region around Oruro; it appears they had the greatest effects further north, around La Paz. There are hints, however, that the Oruro communities purchased their own lands, thus depriving them of the capital that they had used for commerce.Footnote 57 The testament of one community member from Toledo sums up the conundrum well. When Romualdo Choque had his testament written in 1866, he claimed that he owned a number of burros and llamas for his trade, some grazing lands, a house and a small field. However, he declared that ‘I have no cash at all in my possession, nor any goods in kind [especies] of major consideration worthy of mention.’Footnote 58

The assaults on their collective landholdings left the Indian communities reeling, even in the cases where they were able to recoup their lands in 1871. The civil war that raged in the altiplano from 1869 to 1871, when the Melgarejo regime finally fell, also hindered trade. The 1872 law that permitted the free export of uncoined silver from the country also cut into the altiplano Indians' prosperity, since it meant no more smuggling of silver across the border, in all likelihood a well-remunerated activity. The 1872 law also made it possible for mining companies to dominate systems of credit, which eventually helped destroy the rural credit networks, including those of the community Indian merchants who had been able to keep some of their capital.Footnote 59 Another blow was the War of the Pacific (1879–84), which temporarily cut off links to the Pacific coast.Footnote 60 The subsequent construction of the railway that took silver ore from Oruro directly to the coast (the line was completed in 1892) reconfigured trade routes and began to marginalise those who made their living from transporting these materials.

By the late nineteenth century the Indian communities of the altiplano had been pauperised, and most had had to give up their wide-ranging merchant activities. The Indian communities in La Paz again came under full assault by mestizos and creoles for their lands.Footnote 61 The Oruro communities by and large had kept their lands, but at a great cost. They were reduced to working mainly as agriculturalists on very poor fields. Their world had shrunk, from encompassing a vast area from southern Peru to northern Argentina, to comprising only their hamlets, and perhaps also the silver and tin mines to which they migrated now not as merchants but as lowly mine workers.Footnote 62 Rather than participating in the monetary circuit, many retreated to using old pesos febles or depended mainly on bartering arrangements. The state marginalised the Indians in other ways as well; the abolition of tribute that became effective at the national level in 1881 meant that the mutual dependence between indigenous authorities and state officials declined. Whatever commitment the state had made towards protecting the communities and their land base had evaporated. A new ideology brought from Europe that denigrated the Indians and proclaimed them racially inferior became popular among the ruling classes of Bolivia.Footnote 63

Not all Indians suffered equally, as a number either became wealthy without sharing their resources, or tried to jump from indigenous to mestizo status. It is no wonder that in 1899, when the Federalist War degenerated into race warfare, that the leaders of Peñas, in the heart of the formerly wealthy mercantile community region of the altiplano near Oruro, declared a separate Indian republic. Not only that, but once the Peñas Indians had rebelled against the state, they also began persecuting and murdering wealthy Indians who were accused of being ‘landlords and alonsistas [those who followed the Constitutionalist president, Severo Fernández Alonso]’. They accused these men and women of having abandoned communal practices and usurped lands and goods from their communities.Footnote 64

Conclusion

Bringing economic issues back into the debate is important for understanding the roles that indigenous peasants played in the integration of the nation-states in Latin America and in the Andes. This essay has analysed the case of the indigenous peasants of Oruro and western Potosí as a means of showing the importance of economic issues as well as the diversity of responses by indigenous communities to the new challenges of the early republican states. Their case shows that scholars need to go beyond the vision of agrarian peasants to understand better the dynamics of subaltern actions and alliances that resulted in the conformation of republican societies.

Interestingly, the early Bolivian government, like most republican governments as well as present-day scholars, erroneously categorised members of the indigenous communities as intrinsically poor. This generalisation hid the strength and vitality of indigenous peasants in the nineteenth century, who benefited from a state that imposed few fiscal burdens and from undefined and poorly controlled borders. Moreover, the ability to rely on community resources (including social networks embedded in the ayllus) permitted Andean indigenous communities to recuperate more quickly from the devastations of the independence struggles. Their central role as transporters of most goods in the internal and the import-export trades, their participation in regional commerce, and their role as miners and suppliers of most goods for the mining camps and cities was crucial for economic development in the first decades after independence.Footnote 65

This also meant that the economic (and thus political) interests of the indigenous communities diverged from being exclusively related to agrarian pursuits. Many peasants were allied with the mining and import-export merchant sectors and were in favour of free trade, or at least a relatively weak state that had little control over political borders. These economic activities also eventually created greater economic stratification within the communities, although initially both political and economic activities were mediated mainly through the communities and the kurakas.

The assault on community lands and the strengthening of borders from the 1860s onwards exposed the fissures within the communities. This was especially clear in the Oruro region of the altiplano, which had depended heavily on trade and transport for the communities' prosperity. It led to a mounting impoverishment of the majority of the indigenous population and increasing marginalisation, both economically and politically. These fissures created resentment between the majority and the small group of community members who were able to remain wealthy or pass on to mestizo status. Ironically, the Indians who were allied with the opposition Liberal Party during the Federalist War, such as Juan Lero of Peñas, accused the wealthy community members of favouring the Conservatives and, in a fit of class and political violence, executed many of them. Indigenous autonomy was thereafter to be associated with the marginalised poor, but in the decades previously Andean communities had formed the backbone of the economic system and had participated in many ways in the nation-state, although they did not have full political rights. Indeed, their activities as miners and merchants and as the transporters of legal (and smuggled) silver and imported goods, especially evident in the region under consideration, meant that their economic interests lay with a weak state and poorly guarded borders, just like the creole miners and import-export merchants who favoured free trade.