Introduction

Although the transformation of the rural economy and society played a crucial role in the modernisation that Chile experienced from the 1850s to the First World War, historians have hardly studied the agrarian expansion which took place in that period of export-led growth.Footnote 1 In particular, the response of landowners to the growth of demand from both the external and domestic markets, the extent to which the hacienda system underwent a transition to agrarian capitalism, and, if it underwent such a transition at all, how agricultural modernisation affected rural labour have all proved elusive. Yet the established view holds that neither economic modernisation nor social conflict reached the Chilean countryside. The hacienda underwent no substantial changes, for archaic production methods and labour systems remained in place. As a result, the society of powerful landowners and quiescent peasants entered the twentieth century virtually unchanged. Moreover, it is suggested, the ‘backward’ nature of nineteenth-century agriculture was an ‘obstacle’ to economic development, while the persistence of a ‘semi-feudal’ or ‘traditional’ rural society dominated by retrograde landowners prevented political democratisation. The uncritical reiteration of these notions, which are still prominent in general accounts of Chilean history, is related to the limited development of agrarian historiography.

The agrarian historiography of modern Chile is still centred on interpretations established in the foundational studies that Arnold Bauer and Cristóbal Kay carried out more than three decades ago. These works fell short in terms of supporting evidence pertaining to rural estates; thus they did not examine agrarian expansion at the level of the unit of production, and they presented contradictory accounts of the development of the hacienda and its impact on rural labour. Bauer argued that central Chile was a ‘traditional’ rural society that did not modernise under export-led expansion. As land was abundant and labour cheap, landowners expanded production by bringing more land under the plough, extending the labour tenant system known as inquilinaje in a harsher form and hiring more labourers as seasonal peons. Agricultural modernisation was limited to the construction of irrigation channels and the late introduction of machinery in a few model estates.Footnote 2 For Kay, who approached the large estate in Chile from an analytical perspective that draws from late nineteenth-century liberal German agrarian historiography, the ‘hacienda system’ underwent a transition from a peasant-dominated Grundherrschaft to a landowner-dominated Gutsherrschaft, as landowners expanded direct cultivation on the ‘hacienda enterprise’.Footnote 3 Despite its apparent coherence, Kay's discussion of agrarian expansion is not supported by empirical evidence, and borrows from what Bauer argued about the period of the boom in exports in the 1860s and 1870s. Thus, Kay's view on the impact of the agrarian expansion on rural labour is based upon, and actually represents an unorthodox reading of, Bauer's work. Indeed, Kay transformed Bauer's point into the opposite, arguing that, instead of settling more inquilinos on the estates, hacendados began to pay a wage to a number of would-be inquilinos, who swelled the ranks of labourers. The hacienda thus began ‘to depend on the external supply of wage labour’, and reduced the ‘relative importance of tenant labour’ supplied by the inquilinaje system. Along with technological improvements, these changes set in motion the ‘dissolution process’ of the hacienda system, manifested in the ‘proletarianisation’ of its labour force, especially after 1930.Footnote 4

Chilean scholars have added little research to the early historiography, and their views on the hacienda and rural labour between 1850 and 1930 not only borrow extensively from Bauer or Kay's arguments and material, but are actually variations of them. Roberto Santana based his discussion of nineteenth-century agriculture on Kay's work and reiterated the latter's views on changes in rural labour, presenting the impact of agrarian expansion on the inquilinaje system as ‘a case of rural proletarianisation’, which, he added with no evidence, took place in the second half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 5 Gabriel Salazar also briefly discussed the export booms of the 1860s and 1870s, and used Bauer's material to make the case for a rather ambiguous ‘semi-proletarianisation’ of inquilinaje.Footnote 6 Finally, José Bengoa restated Bauer's ‘extension of inquilinaje’, calling it reinquilinización.Footnote 7 In sum, there are contradictory accounts of rural labour based on the same material, and although some scholars have proposed that the main trend was toward the proletarianisation of the hacienda workforce, inquilinos included, that argument has never been substantiated.Footnote 8

Last but not least, the study of social conflict remains a conspicuous lacuna in the historiography of Chilean rural society. Except for Brian Loveman's outstanding works, all accounts of Chilean agrarian history prior to the 1929 Great Depression depict a society in which inquilinos and other hacienda workers were not capable of breaking through paternalistic domination to organise themselves and challenge landowners.Footnote 9 In particular, scholars have regarded rural workers' first expressions of collective action and mobilisation in the early twentieth century as circumstantial, and point out that, unlike other Latin American countries at that time, there were not massive rural revolts in Chile.Footnote 10 Clearly, El llano en llamas was in Mexico, not in Chile. However, historians of rural Chile have not studied social conflict in this period; they disregard it a priori because it does not fit the interpretation of agrarian history which their works have popularised.

This article presents an alternative interpretation of Chilean rural history. It analyses the transformation of the hacienda system and its impact on rural labour during a period in which the agricultural sector underwent an unprecedented expansion in response to the growth of the internal market. The article thus shows that the organisational and technological changes the hacienda system experienced as part of the modernisation of Chile's economy decisively transformed labour systems and shaped the collective action of rural workers. In this light the first rural conflicts, which took place in the early 1920s, can be understood as a consequence of the agrarian expansion that the country experienced from 1870 to 1930. In order to analyse that process at the level of the unit of production, the article focuses on three main questions. How did landowners adjust the hacienda system to respond to the growth of the demand for foodstuffs and agricultural inputs? In what areas, and to what degree, did landowners invest in modernising their properties to make the sustained expansion of the agricultural output possible? How did the organisational transformation of the hacienda system in this era of agrarian expansion change rural labour?

In response to these questions the first part of this article discusses how, during the early phase of the development of the hacienda system, hacendados expanded direct cultivation of the ‘landowner enterprise’ by using labour and other resources from both the precarious peasant enterprises of their inquilinos and through sharecropping. The focus then shifts to the technological improvements – basically irrigation and mechanisation – that allowed landowners to increase the area cultivated and reduce the demand for labour, especially at the peaks in the harvest season. Agricultural modernisation thus emerges as a significant element in the development of the hacienda system because it allowed landowners to marginalise peasant enterprises. This late phase of the system's development, during which the inquilinos' ‘peasant-ness’ became negligible, is discussed in the final section, where the concomitant process of proletarianisation of the hacienda labour force, in response to which inquilinos and other rural workers engaged in unionisation and strikes after the First World War, is also examined.

The Expansion of Landowner Enterprise

The extension of direct cultivation in the landowner enterprise (or demesne, if we employ the conceptualisation developed for the study of the manorial system in Europe) was the starting point of the transition to capitalist production that the Chilean hacienda system experienced from the mid-nineteenth century to the Great Depression. In the haciendas of central Chile this process intensified with the opening of new markets for wheat in California and Australia. Moreover, increasing demand for agricultural foodstuffs also allowed Chilean landowners to export wheat to England, taking advantage of high prices and reduced freight rates. Between 1850 and 1880, therefore, haciendas in central Chile witnessed their golden age through a series of export booms that reached their peak in 1874, but which ended abruptly amidst the economic crisis of 1874–78.Footnote 11

Landowners increased direct cultivation by clearing and improving marginal land on their estates.Footnote 12 In so doing, they relied upon the tenant labour system known as inquilinaje and sharecropping arrangements with both resident and outside workers. This practice allowed workers to carve out internal peasant enterprises that characterised the early stages of the development of the hacienda system. Normally the process of demesne expansion took several years until fields apt for cultivation could be developed, and it required a considerable labour force that landowners secured by providing workers with access to the hacienda's most abundant resource, land. This strategy reflected the landowners' control of most agricultural land and, therefore, the need of poor rural families to gain access to a small plot, even if that meant enduring the unequal and repressive, but nevertheless secure, social order of the large estate. Thus, even though these arrangements were negotiated from completely unequal positions within the hacienda's system of power relations, they offered benefits to both landowners and workers. The former were able to convert an increasing section of their property into effectively cultivated agricultural land with little, if any, cash outlay, and reduce the costs of recruiting and supervising wage labour. As service labour tenants, workers obtained access to the hacienda's resources in the form of a land allotment for their own crops, rights of pasture, a house with a small plot for vegetables, some cash payment, and food rations. Moreover, as sharecroppers, they gained a surplus of produce, which they could sell or use to supplement benefits they already received as inquilinos.

The specific features of the process of demesne expansion, and the role played in it by inquilinos and sharecroppers, can be examined by looking at the development of large haciendas located in different areas of central Chile. One case was that of Peñuelas de Arquén, a 2,700-hectare hacienda in the longitudinal valley, near the city of Talca, just south of the Maule River. The owner improved its once-irregular soils considerably through mixed farming works carried out by sharecroppers, who were the hacienda's same inquilinos. As reported by a correspondent of the Boletín de la Sociedad Nacional de Agricultura who visited Arquén in 1877, the procedure required to improve the soil and prepare new fields for cultivation was quite demanding. First, ‘all shrubs were burnt and their ashes spread out to restore fertility to soils’, which then ‘grew thick grasses after being irrigated and thoroughly tilled’. Next, ‘cattle fed on those natural pastures would provide manure that further enhanced the soil’, allowing the planting of ‘fodder crops such as rye, clover, and alfalfa that were fed to animals on the field itself’, which thus received more ‘manure of excellent quality’. Thus prepared, the fields were:

ploughed and tilled; irrigated by taking advantage of the Maule's overflows; and cultivated with chacras (vegetable crops), demanding sharecroppers to follow explicit instructions for improving soil, which, once those harvests (cosechas chacareras) have been completed, is in condition of entering into the general system of farming adopted on the hacienda and producing, every four years, after other chacarería crops, wheat harvests as satisfactory as those obtained from those fields that can be improved with less work and in a shorter period of time.Footnote 13

As the case of Arquén shows, inquilinaje and sharecropping had an explicit and even thoroughly planned demesne-expanding function that defined their character as social relations. The same role for the system of labour tenancy can be seen on Hacienda Culiprán (or ‘Sweet Waters’, as its owners called it in the 1870s), where the expansion of cultivation accelerated with the introduction of irrigation early in that decade. In this case, workers were not assigned their land allotments (raciones de tierra) on a permanent basis, but only for a year. The purpose of this practice was that through the cultivation of their vegetable crops the inquilinos prepared the fields that were later cultivated with demesne crops. As the owner's grandson recalled, under this method each worker

was allocated by ballot one to four acres of irrigated land for his harvest, and oxen and ploughs … to work it. He was given seed, too, if he wanted it, but he was expected to return the same amount when his harvest was in. As an overseer or skilled craftsman he would get more land than if he was a simple workman. By this means we cleaned and prepared a field for sowing or re-seeding.Footnote 14

Resorting to sharecropping and inquilinaje not only made economic sense for hacendados interested in expanding cultivation, but also reflected the conflict-ridden nature of the relations between landowners and lower-class rural people. In the period of agrarian expansion landowners also used inquilinaje and sharecropping to secure a dependable workforce because it was then, especially in the 1870s with the onset of the nitrate economy, that thousands of men left the countryside and alarmed landowners discussed possible solutions for the ‘rural exodus’. Yet, along with repeatedly complaining about the ‘shortage of hands’, landowners elaborated on their preference for inquilinaje by contrasting it with the risks posed by the ‘floating masses’ of peons. Thus, for instance, in 1875, at the Primer Congreso Libre de Agricultores, an assembly that gathered landowners from virtually all provinces of Chile, Juan N. Espejo voiced a harsh depiction of the peon, stating that not only did he ‘personify all the vices of our working classes’, but also that

he brings to haciendas along with his filthy rags the seeds of moral decay and crime. His work is irregular, slow, and sloppy. His demands are exaggerated in all respects; he complains about the wage, food rations, hours of work. He often takes off with tools or other peons' worthless clothes … [and] rebels for any reason.Footnote 15

In sum, at an early stage of the development of the hacienda system in central Chile, peasant enterprises were not incompatible but functional to the formation and expansion of the landowner enterprise. Yet the expansion of the hacienda system was far more complex than bringing more land under the plough and settling labour tenants and sharecroppers. At the same time, throughout the Nitrate Era, hacendados made substantial capital investments in land-improving and labour-saving technology that would play a major role in the organisational transformation of the hacienda system and the demise of peasant enterprises. Such was the impact of the construction of large irrigation works and the introduction of agricultural machinery.

Map 1.

Both as individuals and through irrigation associations, large landowners carried out a number of impressive and costly projects; the extension of irrigation thus became one of the most significant agricultural investments made during the nineteenth century. The result was the extensive system of canals that criss-crossed the longitudinal valley from Aconcagua to the frontier region by the late nineteenth century. The large areas that these canals irrigated reflect the extent to which haciendas and fundos (large estates, but generally smaller than haciendas) intensified. The region surrounding Santiago, for example, witnessed the expansion of wheat cultivation as a number of canals were built to irrigate the rich properties along the Maipo Valley. The Canal del Maipo, the oldest of such works, was actually a network of channels that by 1870 included the Ochagavía Viejo, Espejo, La Calera, Santa Cruz, San Vicente and Arriagada, all tapped from the Maipo Viejo over the northern sections of the valley. Another section included Pirque, Huidobro, Santa Rita, Viluco, Fernández, Molina, Pachacama and Isla de Maipo, which stretched southwards from the Maipo Nuevo.Footnote 16 The construction of the Mallarauco canal, for its part, was begun in 1873 and finished in the course of 20 years. It provided irrigation for three large properties, Mallarauco, Pahuilmo and Mallarauquito, which together encompassed 7,500 hectares. Similarly, the 59-mile canal that mining entrepreneur Charles Lambert finished, after buying Sweet Waters in the 1870s, transformed this 40,000-acre fundo next to Melipilla ‘from a dry farm, dependent on the six-weeks rainy season in May and June, into a well-watered property with 18,000 acres of irrigated land’.Footnote 17 It was precisely in the Maipo Valley where Julio Menadier, the secretary of the Sociedad Nacional de Agricultura (SNA) and chief editor of its Boletín, witnessed the process of demesne expansion at its peak while visiting Viluco, a large estate on which the area cultivated with wheat more than doubled, rising from 706 hectares in 1861 to 1,621 hectares in 1871.Footnote 18

Irrigation was also instrumental in the diversification of the production of the hacienda system. It allowed landowners to expand other activities that gradually gained in importance, such as livestock raising, viticulture and fruit growing. The wide diffusion of this process may be shown by looking at its impact on haciendas located in different areas through central Chile. From the window of the train along the recently inaugurated Valparaíso–Santiago railway in the 1870s, Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna praised the influence of the Limache canal, which stretched across the hacienda and valley of the same name. He observed that ‘the principal benefits’ obtained from the irrigation of its once ‘barren plains’ were the five-year-old ‘French vineyard’ that included 115,000 plants and yielded 500,000 bottles of wine, and the ‘new vineyard’, which had 300,000 plants expected to bear fruit the following year. Yet the 70-kilometre canal's impact was much larger: it not only provided irrigation for 1,400 of the 1,800 hectares of level land on Hacienda Limache alone, but also supplied the neighbouring haciendas of La Palma, Santa Teresa and Loreto, and the city of Limache.Footnote 19 Livestock raising also required the extension of fodder crops, such as alfalfa and clover; an early example of this was that of Hacienda Catemu, where several canals from the Aconcagua River allowed for the irrigation of approximately 2,500 hectares of land, which, in the colourful words of Vicuña McKenna, had become the ‘alfalfa Eden’. Another observer noted that, further south, on Hacienda Cauquenes, canals had made it possible to bring into production ‘large plains’ which extended along both shores of the Cachapoal River. One canal alone represented an investment of 30,000 pesos, at that time a substantial amount of money, and permitted the irrigation of some 350 hectares that were sown with alfalfa. As a correspondent to the SNA's Boletín noted, ‘all the low vegetation has completely disappeared; only the most robust peumos and quillayes were left to provide shade and shelter to the thousands of head of cattle’. Likewise, on Hacienda El Guaico, near Curicó, over 4,000 hectares were brought under irrigation, presumably for alfalfa, since livestock raising was the hacienda's main activity.Footnote 20 In short, as these examples illustrate, from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, irrigation played a central role in the expansion and diversification of the hacienda system's landowner enterprise.

The expansion of the landowner enterprise also rested on a process of selective mechanisation. This was the landowners' response to the labour supply bottlenecks that hindered the functioning of the hacienda system during the export boom of the 1870s, when the emigration of rural workers became massive. In the long term migration reduced the size of the agricultural labour force and the supply of labour, and also integrated the rural areas into the nationwide labour market created by Chile's economic modernisation, leaving haciendas exposed to competition from other activities such as mining in the northern provinces. In the short term migration caused ‘labour shortages’ in the summer, when the demand for labour reached its peak because a large pool of labourers was necessary for harvesting. Moreover, Chile's economic expansion created alternative sources of employment in the rural areas, such as public works and the construction of railways, which also became more intense in the summer, and thus competed with the haciendas for labourers.Footnote 21 Rural workers took advantage of the seasonal character of the demand for labour and managed to obtain higher wages during the harvest. Analysts of rural society commented on the rise in wages and pointed out that it was a trend that had developed along with the expansion of the hacienda system. In 1873 an article in the SNA's Boletín explained the spread of the mechanical reaper by noting that ‘as a consequence of the shortage of hands’, in many places it was necessary to pay a peon ‘at least 60 cents’ for reaping one ‘task’ (tarea), namely the area planted with wheat that one man could cut in a day. That wage was twice as much as peons earned in the winter.Footnote 22 In 1875, in an essay on ‘the rural worker’ that summarised the discussions of the Political Economy Commission of the Primer Congreso Libre de Agricultores, Juan N. Espejo estimated a wage of 50 cents a task when asserting that a worker ‘cuts 2 or 3 tareas, and earns 1 peso or more’.Footnote 23 Similarly, in his Ensayo sobre la condición de las clases rurales en Chile, Lauro Barros, a prominent hacendado, observed that the ‘wandering peons’ did not work ‘for less than 50 to 80 cents a day’; this was, Barros asserted, the result of the ‘shortage of hands’, itself a ‘logical consequence’ of the increase in the size of the area under cultivation.Footnote 24 Also, in 1875, a more detached observer, Horace Rumbold (the British minister in Santiago), pointed out that ‘the average of wages has increased considerably in recent years’, and noted that the daily wages of the ‘agricultural labourers’ varied ‘between 25 cents and 40 cents, sometimes rising as high as 50 or falling as low as 10 cents’.Footnote 25

Landowners gradually introduced machinery as the foreign commission houses increased the supply of agricultural equipment and the development of a mechanical culture facilitated its adoption in the countryside. The official records for stocks of machinery in the Anuario Estadístico for the 1840–80 period provide a measure of the impact of the export cycle as a stimulus for agricultural modernisation (see Table 1). Other sources also document the process of mechanisation. In 1878 a comprehensive report on the state of Chilean agriculture stated that there were 1,076 reapers and 973 threshers, 424 steam engines, and 1,391 machines of other types.Footnote 26 At the peak of the export boom the scale and pattern of agricultural mechanisation in Chile were in keeping with the supply of available technological innovation, and followed a pace similar to that of older cereal-producing countries. The considerable number of reapers, threshers and steam engines shows that mechanisation developed more in wheat harvest operations than in any other stage of the production cycle. Machinery was concentrated on the most economically dynamic haciendas, and in some cases the use of machines and implements extended to the entire production process.Footnote 27 More importantly, given the nature of the agrarian structure, the number of properties which adopted the use of farm machinery was significant. According to the law of 18 June 1874, which led to an update of the assessed value of all agricultural properties, 666 estates were considered ‘large’ (with an assessed value of $4,000 or more) and 1,513 ‘medium’ ($1,000–$3,000).Footnote 28 Assuming that each property had no more than one reaper, Drouilly and Cuadra's estimates imply that 50 per cent of the 2,179 large and medium estates had reapers.

Table 1. Agricultural Machinery Stocks in Chile, 1864–1874

Source: Anuario Estadístico de la República de Chile. Estadística Agrícola, ‘Máquinas al servicio de la agricultura’, 1865–1874.

However, the impact of mechanisation can be more appropriately considered by examining the extent to which the cultivated area was harvested with machines. Various sources indicate that landowners employed agricultural machines to maximum capacity. The harvest was carried out in the longer-daylight summer months, when the number of work hours could be increased. Chilean hacendados also used the same machines on more than one property, thus extending the equipment's actual number of workdays and performance. Furthermore, custom threshing was common among hacendados and smaller landowners, and, as in other rural societies, there were ‘contractors’ – gringos typically – who specialised in providing custom threshing or renting equipment. In central Chile the area harvested by machines was much larger than has been estimated, since the use of threshers was significant. It is possible to estimate the area that could have been mechanically threshed using data from an 1872 article in the Boletín, which reported the threshing of wheat on two properties near Santiago. The workers used a Ransome thresher which featured a ‘54-inch cylinder’ and was powered by a 10-horsepower steam engine. Starting on 3 January and finishing on 29 March, the harvest extended for 86 days. There were 11 holidays when work was suspended, and seven days dedicated to other tasks, such as bundling sheaves, chopping straw and fixing the machine; the number of days actually used to thresh was thus reduced to 70, without including six days in the first week of February ‘in which we threshed the inquilinos’ wheat'. The work, the source explains, was ‘well-organised, the machine separated the grain from the straw without much loss’, but ‘it was not always possible to have all the necessary workers’. Under these conditions, the Ransome threshed four fields, two on each property, with a total area of 103 cuadras (162 hectares).Footnote 29 Using this figure, and considering the 825 threshers recorded in the Anuario Estadístico, the area mechanically threshed in 1874 would be 133,650 hectares, roughly 30 per cent of the area sown in wheat. In 1878, using Drouilly and Cuadra's estimate of 976 threshers, the area mechanically threshed would increase to 158,112 hectares or nearly 40 per cent.

Agricultural mechanisation continued after the export cycles, when the growth in Chilean agriculture came to depend upon the internal market. The Anuario Estadístico ceased to record machinery stocks after 1874, but trends in agricultural mechanisation can be traced through data on machinery imports, which were recorded in the Estadística Comercial de la República de Chile until 1889 (see Table 2).Footnote 30 A second wave of mechanisation developed from the final decade of the nineteenth century as the area under cultivation rapidly expanded and the demand for equipment increased. The importing companies sought to expand their businesses by means of various marketing strategies, including sales campaigns and credit policies.Footnote 31 In 1907 Chile's Board of Statistics resumed publication of the Anuario Estadístico, thus providing valuable and comprehensive information on machinery stocks. These data series confirm that the second wave of mechanisation expanded in the first third of the twentieth century (see Table 3). By 1910 iron ploughs, tilling tools and harvesting machines were widely used in the production of cereals in Chile. Mechanisation also extended to fodder crops and vineyards. Mowers, choppers and balers were extensively employed for harvesting alfalfa and clover, while the growth of the wine-making industry had stimulated the formation of its own capital goods sector, which was supplied by foreign and Chilean manufacturers. In addition, starting with the introduction of the steam engine in the mid-nineteenth century, large landowners and lesser agriculturalists adopted a series of power sources and types of engines that coexisted with each other and remained in use until the First World War, after which they began to be replaced by gasoline-powered tractors. The quality of mechanisation also improved; it extended to ploughing, with the wide diffusion of metal ploughs and the introduction of tractors. Harvesting equipment was also modernised due to the increased use of specialised machines, namely headers, binders and even combine harvesters.

Table 2. Agricultural Machinery Imports in Chile, 1841–1889 (Units)

* Unspecified agricultural machinery (‘Maquinaria agrícola en bultos’).

Source: Estadística Comercial de la República de Chile: Comercio Especial – Importación.

Table 3. Stocks of Agricultural Machinery in Chile, 1907–1935

Source: Anuario Estadístico de la República de Chile: Estadística Agrícola.

Assessments of rural estates carried out in the 1920s by graduating agronomists at the Instituto Agronómico take us closer to the fields to examine mechanisation further. These informes periciales y tasaciones included detailed information on the economic and social aspects of all kinds of properties throughout Chile, and provide us with a random sample of cases that constitute one of the main new sources used in this study. These reports show that machines and modern implements were introduced mainly in the cultivation of the landowner enterprise's crops, namely wheat, barley, alfalfa and clover, which were cultivated on a large scale and certainly offered possibilities for successful mechanisation. In addition, special ploughs, cultivators and small tractors were introduced on important vineyards that were part of large estates. In contrast, the use of machines in the cultivation of vegetables and legumes proved uneconomic or technically impractical, because in most properties these crops occupied areas that were generally very small and required tasks that were too meticulous for a mechanical implement. The use of machinery also varied among distinct types of properties according to their productive structure, which was related to the geographical characteristics of the areas where they were located. Thus there existed distinct patterns of mechanisation in the different agricultural areas of central Chile in the 1920s (Table 4).

Table 4. Agricultural Machinery in Properties in Central Chile, 1916–1932

* Number of implements not specified in source. h: Wheat reaped by hand. ct: Custom threshing.

Source: Constructed by author using data from Informes periciales y tasaciones, Instituto Agronómico.

At the heart of central Chile, the provinces of O'Higgins and Colchagua formed one of the most representative areas of hacienda-system agriculture. By 1920 the use of threshing machinery was the norm on medium-sized properties, but reaping was frequently done by hand, even in cases where a considerable area was cultivated. This can be illustrated by the Hacienda Antivero, actually an hijuela (daughter estate) of the original huge estate of that name. In 1922, when an agronomist, Victoria Tagle, described it as a property ‘equipped with the machinery and elements of exploitation necessary in a rural estate managed a la moderna’, it had the ubiquitous combination of a steam engine and a thresher, but not a single reaper.Footnote 32 Mechanisation developed most significantly on large haciendas where an abundance of level land and irrigation allowed for large-scale cultivation both of cereals and fodder crops. One such case was the Hacienda La Esmeralda in Colchagua, a province that, because of its shape, was known as the ‘oligarchy's kidney’. Indeed, the hacienda was owned by none other than a former president of the SNA, Raimundo Larraín Covarrubias, and was administered by his son, an agronomist who had graduated from the Catholic University. According to José Espínola, the editor of La Agricultura Práctica and a professor at the Instituto Agrícola, La Esmeralda had 3,000 hectares (ha), 2,155 of which were under cultivation, the crops comprising wheat (637 ha), barley (411 ha), oats (7 ha), clover (328 ha), alfalfa (198 ha) and chacarería crops (450 ha). The case of La Esmeralda shows that even politically conservative landowners, like the Larraíns, could be quite progressive when it came to the use of agricultural equipment. Professor Espínola noted that:

practically all sowing is done by machine on soils that are very well prepared and clean, using three Deering seeders. Besides, there are mowers and reapers of the same make … whose performance is very good. There is also a self-binder, which has not yielded the service it was hoped for. Threshing is done with a Case machine that has given very satisfactory results, and there is also an old-fashioned Ransome thresher used for barley but not wheat because it breaks the grain … There are three steam engines, one Clayton, one Ransome, and one Brown May; experience has demonstrated that the latter is the best one, because it is very firm, smooth to run, and easy to regulate … It has been in service for the past ten years and has never broken down.Footnote 33

Farther south, in the provinces of Curicó and Maule, another characteristic agricultural area of central Chile, there were also important variations in the mechanisation of rural estates. The use of machinery was directly related to the scale of farming among medium-sized fundos. Landowners cultivated a larger area of wheat and fodder crops than coastal properties of a similar size, and thus had a greater degree of mechanisation. These fundos' equipment included the usual steam engine and thresher, but also seeders and reapers, as well as mowers, choppers and balers used in the harvest of alfalfa and clover. Some fundos even boasted tractors, an innovation introduced in Chile during the First World War and diffused more widely in the early 1920s. In short, these types of estate showed what may be considered the most characteristic pattern of mechanisation in central Chile before 1930: animal traction for ploughing and tilling implements and reaping machinery coexisted with steam-powered threshing equipment and, occasionally, the use of tractors.

In turn, there existed remarkable differences in the mechanisation of large fundos and haciendas. The use of agricultural machinery was negligible on estates that extended over the foothills of the coastal range. The case of San Francisco, a fundo near the town of Curepto 110 kilometres east of the city of Talca, illustrates this situation. The property comprised 4,000 hectares, but very little land was suitable for agriculture, for 1,200 hectares were ‘covered by dunes, 450 [were] pastureland over the lomajes that fall toward the sea, and the remainder [were] forests’. Sheep raising was the only economic activity of importance; the fundo barely grew the proverbial chacras of vegetables and legumes, which, as virtually everywhere else, were cultivated without any machinery.Footnote 34 The situation of San Francisco was not exceptional. The coast of Maule was noted for its backward estates. As an agronomist conducting field research observed, ‘In this region agriculturalists are individuals driven by routine, enemies of any innovation suggested to improve the old-fashioned methods of exploitation.’Footnote 35 In contrast, as the case of Fundo San Luis illustrates, some large estates in the valley reached a significant degree of mechanisation before 1930. Located only ten kilometres from the city of Linares, San Luis was owned by the Chilean Match Company and had 1,570 hectares of ‘completely level land’, 300 of which were planted with wheat, 190 with vegetables and legumes, and 320 with alfalfa and clover, while 220 consisted of dairy pasture. The agricultural equipment was worth 30 per cent of the fundo's estimated commercial value, and included two tractors with the accompanying disc ploughs, rakes and cultivators; ploughing, seeding and tilling were thus done mechanically using a variety of John Deere, McCormick, Eckert, Roderick, Hoosier and Rud Sack implements. At the other end of the production process, reaping and mowing were done with eight machines (including two self-binders), while a Case machine powered by a Ransome steam engine was used for threshing wheat and beans (which probably for this reason occupied an unusually large area, 120 hectares).Footnote 36

Mechanisation had a crucial impact on the agricultural sector. It released labour from agriculture and, at the same time, contributed to economic growth. Indeed, a defining element of Chile's agrarian expansion was the gradual reduction in the number of agricultural workers, from 412,568 in 1885 to 353,808 in 1930. Despite this, the agricultural sector expanded in terms of cultivated area and production and also saw a remarkable increase in labour productivity, which can be illustrated with data for the main crops, cereals. In the case of wheat alone, by far the most important crop, the cultivated area grew from 473,429 hectares in 1885 to 773,253 in 1930, while in the same period production rose from 428,422 to 912,437 metric tons. If we consider wheat along with other cereals, the value of output per worker grew from $216 in 1885 to $492 in 1930 (in real pesos of 1910/1914), while the physical output per worker increased from 1,030 to 2,579 kilograms.Footnote 37

The impact of mechanisation on the hacienda system was closely related to the pattern and historical development of this technological change in Chilean agriculture. Since the introduction of machines was prompted by labour shortages in the harvests, the mechanisation of ploughing and harrowing was less significant; tractors were not introduced until after the First World War, and thus ploughing was typically done with iron ploughs pulled by oxen or horses. Likewise, until late in the nineteenth century reaping was predominantly done by hand; however, it needed to be done in the least time possible to prevent losses that occurred when the grain was too dry and shelled out or, in the south, due to early rains. Thus, in large areas of cultivation, reaping by hand was not suitable because it took too long and required a large number of workers. From the 1870s onwards, different types of mechanical reapers for both cereals and fodder crops were gradually diffused among large estates, thus displacing manual methods of harvesting to small properties, isolated areas, or sharecroppers' and tenants' crops. However, as agronomist Roberto Opazo pointed out in 1916, reaping by machine was economic only when the expanse of crops was more than 35 hectares. Thus, except for those properties where the use of mechanical reapers proved not only technically feasible but also economical, reaping frequently remained the work of numerous wage earners, the masses of peones jornaleros who came both from within the hacienda and from the outside (the so-called afuerinos), the latter moving along the central valley and following the harvests in search of temporary employment. These peons cut and bundled the cereal, and were paid by the number of tareas they completed during the day.Footnote 38 As Chilean and foreign agrarian experts repeatedly observed, however, threshers were the agricultural machines most extensively used in Chile; nearly every estate that produced cereals had its own machinery and, in addition, custom threshing was widely used, especially in the south, where even small agriculturists pooled resources to hire contractors and their equipment.Footnote 39

The fundamental change that this harvest-centred process of mechanisation facilitated was the expansion of direct cultivation of the landowner enterprise within the hacienda system, which in turn reduced and marginalised the inquilinos' precarious peasant enterprises. The landowner enterprise thus monopolised the production of commercially relevant crops such as cereals and fodder crops. In fact, given the scale that cereal cultivation reached, on most properties threshing was fully mechanised and done by teams of wage earners made up of both inquilinos and peons, who performed the numerous tasks required for harvesting wheat and other cereals. In short, mechanisation directly contributed to the proletarianisation of inquilinos and the extension of wage labour.

From Labour Tenants into a Rural Working Class

The expansion of the landowner enterprise led to the demise of the social relations that gave workers access to the hacienda system's resources and were the basis of their precarious internal peasant enterprises. In addition to the impact of demographic growth within the lower strata of rural society, this change resulted from technological change in agriculture, particularly the mechanisation of harvests, and the fact that there was a limit to the internal expansion of haciendas and fundos; landowners could not cultivate or exploit all the land on their properties economically. Once clearing and developing new fields ceased to be a pressing need, landowners would not have to cede land suitable for cultivation to the workers. Consequently, from the late nineteenth century sharecropping declined and the inquilinaje system underwent a gradual process of proletarianisation. As a result, at the later phase of the development of the hacienda system, which had emerged by the turn of the century, landowners carried out the regular operations on different crops by resorting to selective mechanisation and labour provided by increasingly proletarianised inquilinos, resident peons and, during the harvest season, outside temporary labourers.

As landowners reduced the size and quality of land allotments, the inquilinos' capacity to sustain their precarious peasant enterprises fell drastically. In the 1870s these labour tenants' plots of land varied greatly, not only from one area or hacienda to another, but also within the same property. Thus, the labour structure within the hacienda system included several categories of inquilinos, differentiated according to the size of their plots and pasture rights.Footnote 40 In the latter decades of the nineteenth century, however, this diversity in land rations and the differences among types of inquilinos were significantly reduced. The reports written by agronomy students at the Agricultural Institute in the 1920s show that a typical ración was then half a cuadra or three quarters of a hectare. In some cases the plots were measured in tareas – that is, small units equivalent to the area of wheat that a worker could reap in one day with a sickle. On some properties landowners converted land allotments into nominal rations, providing no land at all but compensating the worker with a payment in money or kind.Footnote 41 Thus the inquilinos' plots were probably sufficient for the cultivation of vegetables and legumes for the household, but not for producing a marketable surplus of commercially relevant crops such as wheat, let alone fodder crops, which required a large area. Furthermore, as the term ración de tierra para chacras (land ration for vegetables) indicates, landowners explicitly assigned these inquilino plots for the cultivation of legumes and vegetables, crops which did not compete with their own production.

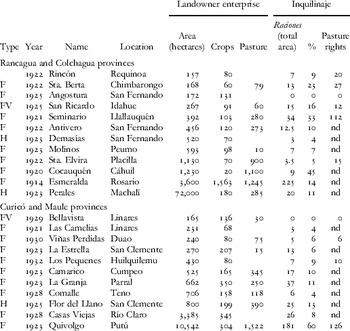

In contrast, the landowner enterprise became the dominant element in the hacienda system. This can be seen in the reports that agronomy students completed in the 1920s, and is illustrated in Table 5, which shows the scope of both the landowner enterprises and inquilinos' land allotments in a sample of properties located in four contiguous provinces of central Chile: O'Higgins, Colchagua, Curicó and Maule. In the properties in O'Higgins and Colchagua landowner enterprises directly exploited most of the estates' resources (2,586 hectares), while the inquilinos' allotments occupied 349 hectares in total. Thus, inquilino families farmed an area that was equivalent to only 15 per cent of that directly cultivated by landowners; this proportion was, however, actually even smaller, since the area left to fallow was normally at least as much as the area sown in a given year.

Table 5. Hacienda Organisation in Central Chile, 1914–1925

C: Chacra; F: Fundo; V: Vineyard; H: Hacienda. nd: no data available.

%: Total area of inquilinos' plots as percentage of area cultivated in landowner enterprise.

Pasture rights: Total number of animals that inquilinos were allowed to keep.

Source: Constructed by author using data from Informes periciales y tasaciones, Instituto Agronómico.

The inquilinos held a significant amount of land only in exceptional cases. These were, in general, small properties on which a reduced portion of the arable land was cultivated; on the other hand, they included Cocauquén, a 1,230-hectare fundo that was ‘exclusively dedicated to sheep raising’.Footnote 42 In contrast, on the estates that cultivated a relatively large area, inquilinos had very little land, as on Hacienda Antivero, or their landholdings had been suppressed, as on Angostura. More importantly, the case of Hacienda La Esmeralda suggests that on very large estates located in the longitudinal valley which cultivated sizeable tracts of irrigated land, landowners had reduced the land allotments of the inquilinos to very small plots. Indeed, rather than being ‘peasant tenancies’, these allotments were too small to grow commercial crops on and were actually only one element among the various components of the workers' remuneration. Thus, on Hacienda La Esmeralda, the inquilino's plot was referred to as ‘ración de tierra para chácaras’ and varied between 0.75 and 2.5 hectares.Footnote 43 In the properties in Curicó and Maule the amount of land cultivated on the landowner's enterprise was also much larger than the area occupied by the inquilinos' allotments. On average, inquilinos' plots occupied an area equivalent to 14 per cent of that cultivated in the landowner's enterprise. This situation is observable on large estates of over 500 hectares, even though the size of the individual plots tended to be larger than the average. On Fundo La Granja, for instance, which had the largest crop area in the sample, the land ration was 2.5 hectares, but the total amount of land distributed among the 18 inquilinos was equal to only 11 per cent of the cropland cultivated in the landowner enterprise. The only property on which inquilinos held a large amount of land, 181 hectares, was Quivolgo, a coastal hacienda dedicated to timber production, which meant not only greater availability of agricultural land but also less pressure on the landowner to exploit it.Footnote 44 In short, on properties in the Curicó-Maule area inquilinos did not have enough land to sustain significantly productive peasant enterprises. Although in some cases they were allotted up to 1.5 hectares, this sample's average plot was a media cuadra or little more than 0.75 hectares, which seems too little land to make the case for a ‘peasantisation of the haciendas’ or a ‘peasant advance’ over the latifundia.Footnote 45

As contemporary observers noted, the expansion of demesne production and marginalisation of inquilinos' peasant enterprises would result in drastic changes in rural labour. Already in the 1870s, at the peak of export-led agrarian expansion, analysts of the Chilean countryside repeatedly denounced the oppressive nature of the inquilinaje system. It is significant not only that such criticism came from certain landowners, but also that it represented a change from the typically paternalistic depictions of rural labour, such as that expressed in the 1840s by the French naturalist, Claude Gay. In his Agricultura chilena, which initiated the scientific study of rural society in Chile, Gay considered that inquilinos constituted ‘a true class in the nation’ which ‘through work and purpose’ could attain ‘all the rights of an independent person’.Footnote 46 By contrast, Ramón Domínguez's law school thesis in 1867 unambiguously stated that the inquilino was ‘a nameless individual, without any relations or future’.Footnote 47 Some hacendados were similarly direct in criticising Chile's peculiar institution. In 1871, a member of the SNA, Santiago Prado, drew attention to the harsh conditions of the inquilinos in the department of Caupolicán, an important agricultural area to the south of the city of Rancagua. He pointed out that ‘the natural thing is that inquilinos farm their lands poorly and belatedly, that they do not tend their chacras, and pick up their crops when the animals that feed on the fallow are virtually on the field’. In addition, Prado lamented that inquilinos' relations with authority ‘verged on the impossible’, because ‘in this place the idea of authority necessarily implies the notion of an unchecked power’, and thus ‘the campesino lives exposed to be squeezed like an orange’.Footnote 48

These remarks reflected the profound transformations in rural labour brought about by the expansion and modernisation of the hacienda system, particularly, but not exclusively, in the system of inquilinaje. For the landless rural poor and members of minifundista families in need of outside employment, the expansion of demesne production made it increasingly difficult to gain access to a plot of land as inquilinos and farm it as relatively independent producers. For the resident inquilinos, especially on the large rural estates that were undergoing modernisation, the expansion would lead to a process of differentiation that constituted the starting point of a process of proletarianisation of inquilinaje as a labour system. This was, in fact, the interpretation that other contemporary analysts of the Chilean countryside advanced. Thus in 1871 another prominent SNA member, Félix Echeverría, joined the debate about the growing emigration of rural workers by rejecting the notion that the so-called ‘rural exodus’ was the inevitable consequence of the peon's ‘wandering idiosyncrasy’. Instead, he asserted that the rural worker emigrated ‘for lack of work’. By that he meant the cyclical character of the demand for labour, which in his opinion was the consequence of the haciendas' concentration on cereals and livestock. Thus while the number of workers employed increased in the summer because of the harvests, it fell drastically in the winter; as a result ‘the worker would see his subsistence shrink’ and would need ‘to undertake other activities’. More significantly, Echeverría explained that ‘when a locality's circumstances’ did not allow the worker ‘to become a small producer’ (hacerse chacarero) he ‘vegetated’, waiting for the landowner to provide him with employment again. Under such circumstances, Echeverría concluded, ‘lacking work even for only two months, the peon emigrates, which is what happens on the fundos in the south of the Republic’.Footnote 49

A few years later the British minister in Santiago, Horace Rumbold, produced an extensive report on Chile's social and economic conditions, including an incisive analysis of rural labour that was especially illustrative of trends developing in the hacienda system. Rumbold straightforwardly concluded that changes in the system of inquilinaje were leading to the formation of a rural working class. By 1875, he was still able to appreciate a clear distinction between ‘the two main groups’ of rural workers in Chile: on the one hand, ‘the inquilinos, or settled peasantry, residing on the haciendas’, and, on the other hand, ‘the great mass of peones, or day labourers, many of whom have neither fixed abodes nor regular ties, and are veritable “prolétaires”, both in the modern acceptation of the term, and in its original sense’.Footnote 50 Furthermore, the British official had no doubt in pointing to the evident proletarianisation of inquilinos, and did not find significant differences between the condition of the Chilean workers under the modified system of inquilinaje and that of English rural labourers. Indeed, polarisation among inquilinos was pronounced. Although there existed a ‘class’ of inquilinos who had attained ‘a rudimentary state of comfort and civilisation’, the ‘far larger number’ of poor inquilinos were ‘hardly to be distinguished from the mass of day-labourers, except for their having settled homes and being held to a certain amount of unpaid service’. Yet, Rumbold added, even this latter group was changing, since:

the poorer ‘inquilino’ receives ordinary payment as a day-labourer, and, indeed, in some parts of the country, the unpaid service to which the ‘inquilinos’ are bound seems to be confined to such exceptional cases as ‘rodeos’ … or else ‘trillas’, or thrashing done by mares where the modern steam-thrashing machinery has not yet been introduced.Footnote 51

In light of these changes, Rumbold remarked that:

In general, it would appear as if paid labour were, by degrees, taking the place of unpaid service, the ‘inquilino’ being thus gradually transformed into a salaried labour, for whom a cottage and patch of garden are provided, as on many English estates.Footnote 52

Furthermore, proletarianisation did not exclusively affect men who were heads of inquilino households. The reduction of the inquilinos' land allotments was decisive for the in situ proletarianisation of other members of their households, both relatives and acquaintances living under the same roof (known as allegados), who increasingly became a source of permanent wage labour from within the estate. Simultaneously, smallholders were being absorbed as seasonal labourers on the haciendas and fundos, next to which they subsisted with difficulty. There was an increasing flow of seasonal wage labourers from the outside, the mass of peons that, as Bauer observes, ‘were absorbed by the transformed hacienda system which required higher labour quotas’.Footnote 53 Thus, inquilinos not only lost their economic capacity as a precarious peasantry, but also became a secondary component of the estate workforce; consequently, the composition and characteristics of hacienda labour changed substantially in the late nineteenth century. An example of the modified labour structure is Hacienda Quilpué, a large property that comprised nearly 4,000 hectares in the rich lands irrigated by the Aconcagua River. In the early 1890s Quilpué had only 69 inquilino families, but between 200 and 300 permanent peons; furthermore, according to the weekly payrolls, the number of peons fluctuated between 414 in June 1892 and 537 in October 1893.Footnote 54

In the first decades of the twentieth century the impact of these trends became even more pronounced. Although the specific content of labour relations varied almost from estate to estate, the agronomists' reports show that throughout all the agricultural areas of Chile the inquilinos were paid a wage that typically represented at least half of their income, and that all types of properties also had a large pool of both seasonal and permanent waged labourers. The fundamental change that inquilinaje underwent may be illustrated by case material. An agronomist's report on Flor del Llano, a fundo of 800 hectares located near the town of San Clemente and 250 kilometres south of Santiago, is particularly informative. In 1925 the fundo's cropland was devoted to the cultivation of 120 hectares of wheat and a vineyard that occupied another 67; there were also 390 hectares of pasture. In the summer and through the early autumn, when the wheat and then the grape harvests were carried out, the demand for labour peaked because, although a tractor and a thresher were employed, the property had no mechanical reapers. Despite this, there were only 36 inquilinos, who made up roughly one third of the resident labour force. As the agronomist explained, the reason was that ‘in each household there is one man who is the inquilino, but also two or more men who work on the fundo as well’. Thus, he added, ‘the fundo has the workers it needs for its exploitation in normal times (100 labourers)’, but ‘in the harvest season people from the outside come, especially from the coast [120 kilometres distant], and complete the labour pool’. Instead of being a self-contained unit, the property was quite open to a significant flow of labourers. Moreover, the proletarianisation of inquilinos was well under way, since they were allotted a land ration of only 0.5 hectares (1/3 de cuadra de chacras), which was part of a mixed remuneration that amounted to $3 per day and was made up of ‘$1.60 in money, $0.70 for the daily food ration, $0.30 for the use of a house, and $0.40 for his chacra’. In turn, the outsiders, or trabajadores forasteros, earned $2.50 a day, and were ‘twice as many as the inquilinos’.Footnote 55

The 1935 Censo de Agricultura provides a nationwide measure of the increasing importance of wage labour and the diminishing significance of inquilinos in the agricultural labour force. The categories employed by Chile's Dirección de Estadística indicate an acknowledgement of the changes that had taken place in rural labour, particularly the inquilinos' increasing dependence on daily wages. The census divided the rural labour force into employees and workers (empleados and obreros), and classified the latter into three groups. The first group was that of inquilinos, which the census unambiguously defined as ‘workers [using the word obreros] who receive a house from the fundo and part of their wage (jornal) in perquisites’. As in the other regions, in central Chile these proletarianised inquilinos constituted roughly one third of the workers (62,175), and were more than the majority in only six of the nation's 25 provinces. The second group was that of ‘peons or gañanes, members of the inquilino and employee households’, which the census defined as those ‘workers who are paid exclusively in money and receive either part or all of their food from the fundo, but no land, house, or pasture rights at all’. This group also included ‘workers who are not relatives of inquilinos but live in the latter's houses’. These peons thus made up another third of the rural labour force (68,675 peons) and were clearly more numerous than inquilinos in central Chile. The final category consisted of the outsiders (peones gañanes or afuerinos), namely those workers who ‘live on the fundo regardless of their payment’ but who were most likely paid a daily wage. In central Chile these workers constituted 28 per cent of the total (59,109 afuerinos), even though the census was carried out at the end of the harvest season, when the demand for labourers tended to decrease. These figures mean that, even without considering inquilinos, if resident and outside peons are taken together, wage labourers comprised two thirds of the agricultural workforce.Footnote 56 In short, data from the agricultural census confirm that, as the hacienda system underwent a protracted transition into capitalist production, the gradual proletarianisation of inquilinos and other hacienda workers resulted in the formation of an incipient rural working class.

A Country Road to National Politics

In the early 1920s, through collective action, rural workers gained unexpected significance in national politics. They engaged for the first time in a wave of mobilisation that included unionisation, strikes, petitions to authorities and even participation in political organisations.Footnote 57 Along with structural transformations in the countryside, political and institutional factors played a key role in shaping rural workers' struggles during the first wave of rural conflicts in modern Chile. Indeed, in this regard Chilean politics in the 1920s illustrates John Walton's observation that ‘in modern society, collective action is increasingly shaped and surrounded by the state’.Footnote 58 The Chilean state provided a new space for workers' political action with the extension of its institutional structure, basically the Labour Office, established in 1905, and its staff of field inspectors, as well as the Alessandri administration's policy, which was initially aimed at facilitating negotiation in conflicts between capital and labour. Similarly, especially in haciendas located near to urban centres, the growing activism of Chilean Federation of Workers (FOCh) ‘agitators’ and pampinos crowded in the hostels established in Santiago to contain social unrest provided a political language and organisational resources for rural workers to challenge landowners.Footnote 59 Yet, these institutional and political factors operated in a countryside that had changed substantially because of the agrarian expansion. By the time of the First World War inquilinos and other hacienda workers were, as Loveman also noted, more of a ‘rural proletariat’, as they had become more dependent on wages than on in-kind perquisites.Footnote 60 Moreover, rural workers had come a long way from less dramatic forms of social protest, such as stealing, work slowdowns or the apparently accidental damage of hacienda resources, all of which were characteristic in Chilean haciendas and which, following James Scott, can be understood as rural workers' everyday forms of resistance.Footnote 61 Thus, not only did they typically demand higher wages in labour petitions presented to estate administrators or hacendados, but they also adopted new forms of collective action, such as strikes and unionisation, frequently but not always carried out with participation from the urban proletariat with which they had begun to work through the FOCh's federal councils. A brief description of a strike at Culiprán (the Lambert family's ‘Sweet Waters’), a large hacienda near the town of Melipilla, east of Santiago, illustrates the social conflict that was taking place in rural society.

In February 1921, at the peak of the harvest season in central Chile and less than two months after the inauguration of President Arturo Alessandri, the inquilinos of Culiprán went on strike and formed a ‘federal council’ affiliated with the FOCh. Local FOCh activists and a group of inquilinos initiated the movement because the administrator had imposed an extended work day and, after the workers protested against the measure, fired three men. The climate created by several strikes throughout the country may explain the authorities' interest in ‘solving’ the strike at Culiprán. Summoned to a meeting with the governor of Melipilla, the inquilinos presented their demands: higher daily wages, ‘gradual improvement’ of their housing, ‘absolute freedom to vote’, and the rehiring of the three dismissed workers. The landowner's representatives agreed to all these points, but the hacienda's owner, Mrs Lambert, refused to confirm the agreement. In response, the workers demanded the intervention of the minister of the interior, while the FOCh declared that its provincial councils would meet daily to support the strike. Alessandri then instructed the intendant of Santiago, Alberto Mackenna, to help find a solution to the dispute. Mackenna met with the inquilinos on the hacienda a week after the strike began. Although ‘several individuals who did not belong to the hacienda’ interrupted him with ‘yells of protest’, the intendant managed to read out the owner's ‘concessions’. The owner, Mackenna explained, would not acknowledge the ‘federal council’ and insisted on firing a worker known to be a ‘rebellious individual’. In the evening, after hours of deliberation, a group of inquilinos approved the new terms Mrs Lambert had offered and expressed their intention to resume work. An indeterminate number of workers persisted with the strike, however, despite the fact that the government had just sent ‘more military forces’ to the area, where ‘all landowners praised the efficacious and opportune action of the Intendant and the police’. Samuel Infante, for instance, sent a telegram stating that thanks to Mackenna's intervention the situation was ‘getting back to normal as more workers from all the fundos on strike have come out [to work]’. Meanwhile, as a commission of workers met with Alessandri and asked him to broker a definitive solution to the conflict, Mrs Lambert sent him a letter calling the strike ‘unfair’ and ‘subversive’, and declaring that she refused to recognise the federal council because it represented an unacceptable intervention by the FOCh. In the end, except for that demand, she agreed to all the petitions, and after two weeks on strike, 85 inquilinos and 100 workers in the hacienda's flour mill returned to work.Footnote 62

The Culiprán strike shows that rural conflicts had a direct impact on national politics during Alessandri's troubled first term in office. The strike also indicates the dependence of proletarianised inquilinos on their wages, which explains why one of their primary goals was to gain a wage rise. More importantly, these movements involved collaboration between campesinos and activists of the national labour movement, which also responded to the FOCh's strategy. Last and by no means least, as part of those campesinos' historical memory, the early conflicts would also inform their role in other struggles in the countryside, such as those related to the agrarian reform of the 1960s. In fact, more than 40 years later, one of those inquilinos would explain his leading role in the 1965 seizure of Hacienda Culiprán by recalling his participation in the 1921 strike:

I was born and raised in this very house. I was ten when Arturo Alessandri Palma was elected, and this hacienda was the first to go out on the strike called by the Federación Obrera de Chile. After that we marched to Melipilla. That night – I was ten and shivering from the cold with my parents – we marched. We marched and we gained a little ground. In those days my father was making 80 cobres [cents] as an inquilino on the hacienda, but after the strike he made 1.20 pesos – they gave him a rise of 40 cobres.Footnote 63

The Lamberts had owned Culiprán since the early 1870s, when the mining entrepreneur Charles Lambert began to develop it with considerable investments in irrigation works and, perhaps envisioning the benefits of irrigation, changed its name to Sweet Waters. By 1921 Culiprán had remained in their hands for almost half a century, but in the charge of administrators, as was the case with many rural estates; indeed, in a letter sent to the authorities Mrs Lambert described herself as an estate owner who ‘had just arrived to Chile to take care of her businesses after long years of absence’. The strike can thus to some extent be attributed to her inability to fashion paternalistic methods of social control, a problem which foreign landowners may have experienced more frequently than Chilean hacendados. However, as the telegram that the hacendado Lazcano sent to the intendant suggests, the Culiprán strike was neither atypical nor an isolated case.

In fact, the Culiprán strike was part of a wave of rural mobilisation which took place throughout the country and followed a clearly discernible pattern. Workers went on strike not only to confront landowners and administrators, but also to advance their demands through the institutional framework provided by the state's Labour Office, while the FOCh activists worked to integrate the rural proletariat into the nation's growing labour movement. In 1921 there were 2,600 rural workers affiliated to ‘federal councils’, and in October that year the FOCh organised the Primera Convención de Campesinos, whose main demands were an eight-hour work day and a minimum daily wage of $5.Footnote 64 Also in 1921, rural workers carried out strikes through the year in different agricultural areas scattered throughout central Chile, from the province of Valparaíso to Arauco. The Labour Office documented some of these strikes, as on Fundos Mansel and Las Camelias, next to Hospital, a town south of Santiago (21 January); Hacienda Colcura, in Arauco province (4 February); Fundo La Peña in Quillota (18 April); Hacienda Aculeo, where the inquilinos presented a labour petition and went on strike after refusing to wait until the administrator consulted with the landowner (25 April); Fundo El Escuadrón (20 May); Hacienda El Melón, next to the town of La Calera, where ‘agitators’ reportedly set fire to numerous hay bales (25 July), and where by September the inquilinos were on strike demanding a daily wage of $2.80; Fundo Las Chacras, near Valparaíso (8 August); Fundo Con Con, next to Limache, where the inquilinos had formed a federal council affiliated with the FOCh (15 August); in San Clemente, where a strike instigated by ‘agitators from the north’ apparently failed (15 August); in several fundos in Llay Llay, where an indeterminate number of inquilinos were evicted because they had joined the FOCh's federal councils (19 August); Hacienda La Rinconada de Chena, south of Santiago (24 September); and fundos El Ingenio, Las Higueras and Quebradilla, all in the vicinity of the town of La Ligua and where the strikes were solved through negotiation (26 September). Furthermore, rural unrest in the countryside continued through the summer of 1922.Footnote 65 In response, landowners turned to direct persecution and repression by the police, while the influential Sociedad Nacional de Agricultura, the large landowners' main organisation, pressured Alessandri to curtail rural activism.Footnote 66 For their part, mainstream newspapers like El Mercurio echoed the landowning elite's campaign against what they depicted as the intervention of Bolshevik agitators. Clearly, the social conflict that threatened the stability of Chile's political system in that critical decade had also reached the countryside.

Conclusion

The period from the 1870s to the 1920s witnessed not only the expansion and increasing commercialisation of agriculture, but also the hacienda system's transition to capitalist production. This transformation started in the 1860s and the 1870s, with the opening up of export markets for wheat, the main staple of Chilean agriculture, and proceeded decisively thereafter in response to the growth and integration of the domestic market. It was certainly not completed by 1930, and its development was retarded by the negative impact of the Great Depression. Yet through that period, as landowners extended irrigation and selective mechanisation, they reduced the inquilinos' land allotments and restricted sharecropping, thus weakening the social relations that allowed rural workers access to hacienda resources. In this way, as the landowner enterprise came to dominate the cultivation of commercially relevant crops and livestock raising, its expansion led to the demise of the precarious peasant enterprises of the labour tenants.

In the transition to agrarian capitalism in central Chile the formation of the rural working class did not begin with the violent expropriation of an independent peasantry. Instead, proletarianisation was a decades-long process that transformed inquilinos from labour tenants into resident wage labourers, while at the same time integrating their family members, outside minifundistas and the rural poor into the hacienda system's workforce as seasonal labourers. Although inquilinos continued to be paid with a mix of fringe benefits and cash, their subsistence came to depend on their income as resident workers, and, as such, their perquisites were just a part of their remuneration and calculated in monetary terms.

The gradual proletarianisation of the hacienda system's workforce led to the formation of a rural working class. By the time of the First World War, especially on large haciendas which employed a sizeable labour pool, rural labourers worked according to an extended division of labour that rationalised the different production processes on the hacienda, from the preparation of the fields to harvests of various sorts. Hacienda workers were also subjected to a work discipline, signalled by the bell at the property's gate or the harvest machine's whistle. Above all, inquilinos and peons were dependent on an income in which the daily wage or jornal represented at least half, or more, of household income if that of other household members such as the men, women and children also employed by the hacienda is considered. Illustrative of their condition as resident labourers whose subsistence depended primarily on earning wages is the fact that, as we saw in the Culiprán strike, rural workers' petitions invariably placed wage rises for inquilinos, voluntarios and women as a priority among their demands.Footnote 67 In fact, in 1929 the Department of Agriculture acknowledged the focus of strikes and the impact on rural wages, attributing their increase during the previous decade to the ‘labour movements of 1919 and 1920, which extended strikes to agricultural workers’.Footnote 68 Thus, in the crisis that followed the First World War, labour activists found fertile ground in the countryside because the condition of rural workers had changed substantially with the transformation of the hacienda system. Indeed, the participation of rural workers in these and other collective actions signalled the beginning of a new era in the labour movement. Changes in rural labour systems had ended the precarious ‘peasantness’ of the inquilinos, and thus left no prospects for ‘peasant revolts’. Instead, as FOCh agitators clearly understood, the countryside was getting ready for them to embark on the rather difficult task of integrating rural workers into the mainstream of working-class politics.