Introduction

Vertigo, dizziness and disequilibrium are subjective sensations that usually result from a disease of the vestibular system. Determining the type of vestibular disorder is critical, as evaluation and treatment differ markedly depending on which disorder is present. In elderly individuals, vertiginous disorders are very common.Reference Baloh1 These disorders are usually difficult to diagnose in older adults, who frequently have co-morbidity and a wide range of potential causes for physical instability. Vertiginous disorders may also lead to falls in the elderly, which are associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality.Reference Lee, Yi, Lee, Ahn and Park2 Although vertiginous disorders may represent a life-threatening condition in elderly patients, most are benign and self-limited.Reference Baloh1, Reference Boult, Murphy, Sloane, Mor and Drone3–Reference Salvinelli, Trivelli, Casale, Firrisi, Di Peco and D'Ascanio5

Two factors combine to make balance disorders in the aging population a major healthcare problem. The first is a sharp rise in the elderly population in the developed countries. The second factor is the increasing difficulty patients have with balance problems as they age. The elderly have increasingly greater difficulties with sensory function, central nervous system interrelation, and neuromuscular and skeletal function. Also, chronic illnesses such as atherosclerosis may damage labyrinthine functions and also cause peripheral vascular occlusion. Diabetes mellitus not only accelerates atherosclerosis, but also causes peripheral neuropathy.Reference Salvinelli, Trivelli, Casale, Firrisi, Di Peco and D'Ascanio5

It is an unpleasant truth that patients with vertigo often get little satisfaction from clinicians unless the underlying cause is known. Thus, studies that focus on the identification of vertigo aetiology are important.

The aim of this retrospective analysis was to evaluate the diagnosis of vertigo, dizziness and imbalance in elderly patients who had been followed up in two tertiary neurotology clinics.

Patients and methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted by the same senior author within two tertiary centres – the Vertigo and Balance Center of the Marmara University Institute of Neurological Science, and the Neurotology and Balance Center of the Acıbadem Health Group Kozyatagi Hospital – over a period of six years (1999–2005). The study protocol was approved by the ethical board of the hospital. Six hundred and seventy-seven patients over 65 years old who had been referred with vertigo, imbalance, or both were retrospectively evaluated.

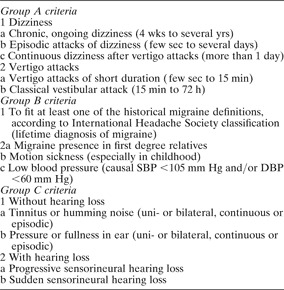

Ménière's disease was diagnosed according to the 1995 guidelines of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery.6 Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) was defined as transient vertigo induced by Dix–Hallpike testing with video nystagmo graphy (VNG), associated with characteristic paroxysmal positional nystagmus and response to canalith repositioning manoeuvres.Reference Oghalai, Manolidis, Barth, Steward and Jenkins7–Reference Lea, Kushnir, Shpirer, Zomer and Flechter9 In order to define idiopathic vestibulopathy and migraine vestibulopathy, we developed an algorithm, using the criteria shown in Table I, as follows. The patients were considered to suffer from migraine vestibulopathy if they had: at least one of the criteria from group A plus criterion one from group B; or two criteria from group B subclass two (after exclusion of other causes of vertigo). There might be one of the criteria of group C. Idiopathic vestibulopathy was described, after exclusion of other well known vestibular disorders, if the patients had one criterion from group A; one of the criteria from class C might also be present.

Table I Criteria for classification of vestibulopathy and migraine

Wks = weeks; yrs = years; sec = seconds; min = minutes; h = hours; SBP = systolic blood pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure

Patients with additional neurological diseases were excluded from analysis.

Results

We excluded from analysis 24 patients (3.54 per cent) with middle-ear pathology, 18 (2.65 per cent) with cerebral ischaemic lesions, 11 (1.62 per cent) with other additional neurodegenerative diseases, and 23 (3.39 per cent) with osteoarticular pathology. Thus, a total of 601 individuals between the age of 65 and 92 years were enrolled in the study. There were 214 (35.61 per cent) men and 387 (64.39 per cent) women.

Patients were assigned to diagnostic groups. The major diagnostic groups were BPPV (n = 255, 42.43 per cent), idiopathic vestibulopathy (122, 20.29 per cent), migraine vestibulopathy (79, 13.15 per cent) and Ménière's disease (75, 12.47 per cent). Acute vestibular attack (39, 6.49 per cent) was a less common diagnosis (Table II). Twenty-five (9.81 per cent) patients with BPPV had bilateral disease, 15 (5.88 per cent) had horizontal canal involvement and eight (3.13 per cent) had multiple canal disease (Table III).

Table II Distribution of disorders causing vertigo

Table III Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: disease site subgroups

One hundred and forty-five (57 per cent) patients classified as having BPPV also had migraine vestibulopathy, 53 (21 per cent) also had idiopathic vestibulopathy, 11 (15 per cent) also had Ménière's disease and two (0.7 per cent) also had acoustic neuroma (these patients are classified under BPPV in Table II).

Systemic disorders manifesting as vertigo were detected in 11 (1.83 per cent) patients with vascular lesions, including vertebrobasilar insufficiency, atheromatous disease and hypothyroidism.

Post-traumatic vertigo was detected in five (0.84 per cent) patients, following blunt trauma of the head, neck and craniocervical junction. Ototoxicity was the cause of vertigo in 10 (1.67 per cent) patients, all due to aminoglycoside usage. Three patients (5 per cent) had acoustic neuroma and two (0.34 per cent) had incapacitating motion sickness (which is rare in older age groups).

Discussion

Vertiginous disorders causing balance problems are commonly found in older age groups.Reference Konrad, Girardi and Helfert4–Reference Oghalai, Manolidis, Barth, Steward and Jenkins7 As stated by Konrad et al., Reference Konrad, Girardi and Helfert4 two factors combine to make balance disorders in the aging population a major healthcare problem. The first is a sharp rise in the elderly population in the developed countries. The second factor is the increasing difficulty patients have with balance problems as they age. The elderly experience increasing difficulty with sensory function, central nervous system interrelation, and neuromuscular and skeletal function. Also, chronic illnesses such as atherosclerosis may damage labyrinthine function and may also cause peripheral vascular occlusion. Diabetes mellitus not only accelerates atherosclerosis but also causes peripheral neuropathy.Reference Salvinelli, Trivelli, Casale, Firrisi, Di Peco and D'Ascanio5

In this retrospective clinical analysis, we found BPPV to be the most frequent disease (42.43 per cent) causing vertigo in our elderly patient population. Women were more susceptible than men, and the posterior canal was the most affected site. Although it is often underestimated because its diagnosis is difficult in elderly patients, the prevalence of BPPV is known to increase with age.Reference Oghalai, Manolidis, Barth, Steward and Jenkins7–Reference Lea, Kushnir, Shpirer, Zomer and Flechter9 In a cross-sectional study within a poor, inner city, elderly population, Oghalai et al. Reference Oghalai, Manolidis, Barth, Steward and Jenkins7 reported a prevalence of dizziness as high as 61 per cent. Balance disorders were found in 77 per cent of subjects, and 9 per cent were found to have unrecognised BPPV. Oghalai et al. emphasised the high rate of unrecognised BPPV in their study group. They also noted that BPPV was present in a certain subset of patients who did not actively report a balance disorder, but instead complained of associated limitations of function. Moreover, because physicians tend to refer such cases less often, being aware of the condition's distinguishing characteristics and good prognosis, its frequency is probably greater than indicated.

Another important group in our retrospective study were patients diagnosed with migraine vestibulopathy (13.15 per cent). This diagnosis was more common than Ménière's disease. Vertigo associated with migraine in adults is a more difficult entity to classify. The clinical association of dizziness and migraine has been noted since an 1873 publication by Liveing.Reference Liveing10 However, it is still difficult to prove a causal relationship between migraine and any of the transient symptoms that may accompany it. Bramwell and McMullenReference Bramwell and McMullen11 noted in 1926 that many neurological symptoms associated with migraine headache, including episodic vertigo, may also occur without headache. Over the last few decades, an understanding of the causal relationship between vertigo and migraine has evolved from several patient–control series.Reference Bramwell and McMullen11–Reference Uneri13 The clinical association of migraine and vertigo has been supported by case–control studies of patients presenting with dizziness;Reference Uneri13–Reference Lempert and Neuhauser15 inversely, vertigo has been found to be more common in patients with migraine than in controls.Reference Lempert and Neuhauser15, Reference Crevits and Bosman16

A high number of patients (n = 122, 20.29 per cent) in the present study had been diagnosed and followed up as having idiopathic vestibulopathy. In this group, the most important diagnostic criterion was the exclusion of well defined peripheral vestibular disorders. Neither auditory symptoms and audiological findings nor vertiginous manifestations and vestibular examination signs were indicative of any specific group of disease. Radiological studies were normal. Systemic evaluations, including cerebral and cerebellar function testing, vertebrobasilar system investigations and hormonal profiling, were normal. In these patients, hearing may be affected, and tinnitus can occur and may accompany vestibular attacks.

Classification of these patients as a different group within the diagnosis of idiopathic vestibulopathy might be biased, as this classification concerned only patients' clinical presentation and long-term follow up and was not intended to signal underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. In addition, the present study concerned only elderly patients, and only proportions of disorders are presented. Although patients were followed up for a period of one to six years, their conditions may have changed to known disorders over that course of time. Despite these arguments, our classification enabled our patients to be treated and followed up better, with improved quality of life and long disease-free intervals, over the one to six year study period.

Ménière's disease was another common inner-ear disease (n = 75, 12.47 per cent) causing vertigo in our retrospective evaluation, with women being predominantly afflicted. In the elderly, Ménière's disease is considered rare, but little precise data are available in this population.Reference Baloh, Jacobson and Winder17–Reference Ballester, Liard, Vibert and Hausler19 Ballester et al. Reference Ballester, Liard, Vibert and Hausler19 retrospectively analysed 8423 neurotological clinic visits and reported that 432 (5.1 per cent) patients had Ménière's disease, and that 66 (15.3 per cent) of these patients were over 65 years old. They concluded that Ménière's disease in the elderly is not rare. These authors concentrated on two different forms of Ménière's disease: de novo disease (40.9 per cent) and reactivation of long-standing disease (59.1 per cent).

• The aim of this retrospective analysis was to evaluate the diagnosis of vertigo, dizziness and imbalance in elderly patients attending two tertiary neurotology clinics

• The most frequent diagnoses were benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (42.43 per cent), idiopathic vestibulopathy (20.29 per cent), migraine vestibulopathy (13.15 per cent), Ménière's disease (12.47 per cent) and acute vestibular attack (6.49 per cent)

• Peripheral vertigo was diagnosed in 93.5 per cent of patients, possibly amenable to treatment

• This high percentage of peripheral disorders might be due to most patients being referred to the specialised neurotology clinics from otorhinolaryngological and neurological clinics

It is well known that BPPV is common in the elderly, particularly in patients presenting with complaints of dizziness. It is also well known that BPPV can occur together with other peripheral vestibular disorders. In the present study, cases of such comorbidity were classified as BPPV.

Acute vestibular attack is another common cause of vertigo in older adults, and typically presents with a dramatic, sudden onset of vertigo and attendant vegetative symptoms. Dizziness lasts for days, with gradual, definite improvement throughout the course. However, it is a frightening disorder that often precipitates a visit to the emergency department. The present study found 39 (6.49 per cent) patients with acute vestibular attack, men and women being affected equally.

Conclusion

In the present study, 93.5 per cent of elderly patients were diagnosed as having peripheral vertigo. The majority of patients were classified as having BPPV, idiopathic vestibulopathy or migraine vestibulopathy, all of which may be treated successfully. Presumably, the cause of this high percentage of peripheral disorders might be due to fact that most patients had been referred to the authors' specialised neurotological centres from otorhinolaryngological and neurological clinics. In this report, we present a different clinical classification of vestibular disorders in elderly patients. We also propose a re-evaluation of the diagnosis of balance disorders in elderly patients.