Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is the most common form of sleep-disordered breathing and is characterised by recurrent episodes of complete or partial upper airway obstruction during sleep resulting in oxygen desaturation, autonomic dysfunction and sleep fragmentation. Clinical symptoms include loud snoring, witnessed apnoeas, nocturnal choking and excessive daytime sleepiness. Overnight polysomnography is the ‘gold standard’ for the diagnosis of OSA. Based on the apnoea–hypopnoea index, OSA is classified as mild when the apnoea–hypopnoea index is between 5 and 15, moderate when the apnoea–hypopnoea index is between 15 and 30, and severe when the apnoea–hypopnoea index is greater than 30 episodes per hour.

A recent systematic review showed that the overall population prevalence of OSA varies from 9 to 38 per cent as a result of the methodological heterogeneity of the studies.Reference Senaratna, Perret, Lodge, Lowe, Campbell and Matheson1 Although OSA is common, it is a frequently unrecognised cause of serious disability that has important health and social consequences. If untreated, OSA can lead to sequelae including cardiovascular events, strokes and traumatic injury related to road traffic collisions and is also associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality.Reference Marin, Carrizo, Vicente and Agusti2–Reference Marshall, Wong, Liu, Cullen, Knuiman and Grunstein5

Patients with untreated OSA are more likely to visit a health professional or require hospital admission because of symptoms directly or indirectly associated with OSA.Reference Marin, Carrizo, Vicente and Agusti2 Healthcare resource utilisation costs are reported to be 19.9 per cent higher in untreated OSA prior to diagnosis and treatment.Reference Walter, Hagedorn and Lettieri6 In contrast, treating OSA is associated with improvement of OSA-related morbidity and quality of life for both patients and partners, increased work productivity, and cost savings for the National Health Service (NHS).7,Reference Rejon-Parrilla, Garau and Sussex8 According to a health economics report in 2014, although 1.5 million adults were estimated to have OSA in the UK, only 330 000 were receiving treatment.Reference Rejon-Parrilla, Garau and Sussex8

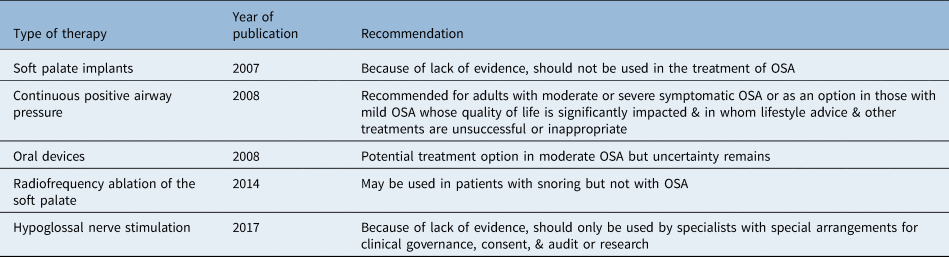

Various therapeutic options for OSA exist in published guidelines worldwide, including lifestyle changes, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), oral appliances and surgery.Reference Mandavia, Mehta and Veer9 Although CPAP is considered the ‘gold standard’ treatment for OSA,7,Reference Epstein, Kristo, Strollo, Friedman, Malhotra and Patil10 its clinical application can be compromised by intolerance and poor compliance with non-adherence rates between 46 and 83 per cent.Reference Weaver and Grunstein11 For that reason, alternative treatment options have been considered, and although their success rates and implications vary, there has been a growing body of evidence supporting the role of mandibular advancement devices and sleep surgery in carefully selected patients. The UK guidance published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) does not cover the majority of these options as shown in Table 1.7,12–14 As a result, individual health boards have produced their own funding policies. The aim of this study was to review the funding policies for the treatment of OSA across various NHS Trusts in England.

Table 1. Published national NICE guidelines for the management of adult patients with OSA

NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; OSA = obstructive sleep apnoea

Materials and methods

We reviewed the published funding policies from a range of health boards, currently referred to as clinical commissioning groups. From the NHS England list of 190 clinical commissioning groups, a sample of 60 was randomly selected. For each clinical commissioning group, a web search was performed between 9 and 16 December 2019 for any published documents (hosted either on the clinical commissioning group's website or otherwise bearing the clinical commissioning group's name) which featured relevant search terms, varying these methodically if no policy was found. For example, for the CPAP policy in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough clinical commissioning group, the search terms ‘sleep apnoea’ and ‘cpap’ were sufficient to find the appropriate policy regarding CPAP for OSA on the website www.cambridgeshireandpeterboroughccg.nhs.uk; otherwise, the variations ‘osa’, ‘osahs’, and ‘continuous positive airway pressure’ would be used in turn.

We included policies relating to the management of OSA and excluded those that related only to primary snoring. We reviewed the funding criteria for patients with mild, moderate and severe OSA for the following treatments: CPAP; oral appliances including mandibular advancement devices; tonsillectomy; palatal surgery including radiofrequency, laser, implants and other surgical techniques; tongue base surgery including radiofrequency, laser and robotic surgery; nasal surgery including septoplasty; hypoglossal nerve stimulation; and mandibular surgery. We noted whether each treatment was funded based on a clinical assessment alone; on a set of criteria given by the clinical commissioning group; on an exceptional case-by-case basis; not funded at all; or whether no guidance was provided.

Results

We reviewed the funding policies from 60 clinical commissioning groups as shown in Table 2. There was a geographical distribution across the country with 8 clinical commissioning groups from North England (North East, North West, and Yorkshire and the Humber), 10 from the Midlands (East and West), 8 from East Anglia, 10 from London and 24 clinical commissioning groups from South England (East and West). The results are summarised in Table 3.

Table 2. List of clinical commissioning groups and geographical distribution*

* n = 60. CCG = clinical commissioning group

Table 3. Proportion of clinical commissioning groups funding each therapeutic option for obstructive sleep apnoea management

Values are numbers of clinical commissioning groups (per cent). *n = 60; †intervention is funded if patient is deemed to require it clinically; ‡intervention is funded if patient meets certain criteria; **intervention is only funded on an individual patient basis in exceptional cases; §intervention is not funded; #data is not available in the policy

For treatment options covered by current NICE guidance, there was a degree of similarity across clinical commissioning group policies. Continuous positive airway pressure was funded based on a clinical assessment or according to criteria that were in line with NICE guidelines in most clinical commissioning groups (21 of 60 and 28 of 60, respectively), with 11 clinical commissioning groups offering no policy.

Mandibular advancement devices were funded based on a clinical assessment in 6 clinical commissioning groups and based on certain criteria in 10, with the remainder either not providing funding or not providing guidance (8 of 60 and 36 of 60, respectively). Soft palate surgery was mainly not funded (13 of 60) or funded only in exceptional cases (19 of 60), with one clinical commissioning group offering criteria-based funding and the remainder not providing guidance (27 of 60). The criteria included excessive sleepiness and OSA refractory to CPAP and lifestyle changes. Hypoglossal nerve stimulation was not mentioned in any clinical commissioning group's policy.

In areas not covered by NICE guidance, there was a greater variation in funding. Tonsillectomy was funded only in exceptional cases in half of the clinical commissioning groups but was available based on criteria in a significant minority (24 of 60) and funded based on a clinical assessment in one. The criteria in these cases ranged from large tonsils to failure of conservative management or CPAP. Similarly, nasal surgery was funded based on criteria in some clinical commissioning groups (16 of 60) and not normally funded (23 of 60) or not covered by guidance (21 of 60) in others. Criteria for nasal surgery generally included significant nasal obstruction refractory to medical therapy over a given period (e.g. six months).

Funding for procedures involving the tongue base was available in one clinical commissioning group for patients with moderate-to-severe OSA who had failed to benefit from lifestyle measures and CPAP. Twenty-six clinical commissioning groups stated that these procedures were not normally funded. The remaining clinical commissioning groups either did not provide funding (6 of 60) or did not provide guidance (27 of 60). Likewise, only one clinical commissioning group provided funding for mandibular surgery based on the above criteria with the remainder either not providing guidance (34 of 60) or not normally funding the procedure (25 of 60).

Discussion

The current UK healthcare commissioning system was created by the Health and Social Care Act 2012 with a view to increasing competition within the NHS. Although some specialised services are commissioned by the national body, NHS England, most services are commissioned locally by individual clinical commissioning groups. Where national guidance is available from bodies such as NICE, there tends to be some consistency in the provision of services. However, where such guidance does not exist or is historical in nature, individual clinical commissioning groups conduct their own reviews and may come to different conclusions or may have differing priorities. This produces an inequitable variation in the availability of treatment depending upon the patient's geographical location and may unnecessarily restrict the availability of procedures for which there is now good supporting evidence.

CPAP

Continuous positive airway pressure is currently the therapy of choice for OSA, and our study shows that it is funded by the vast majority of clinical commissioning groups in England. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends CPAP use as the primary treatment for patients with moderate or severe OSA and as an option for patients with symptomatic mild OSA if lifestyle changes and other relevant therapies have failed or are considered inappropriate.7 A recent randomised trial showed improvement of quality of life in patients with mild OSA after a three-month trial with CPAP.Reference Wimms, Kelly, Turnbull, McMillan, Craig and O'Reilly15

However, the effectiveness of CPAP is often undermined by low adherence as a result of intolerance. Although alternative treatment modalities exist, current NICE guidance does not include any of these in case of CPAP failure. Furthermore, there is evidently a great variation in funding, with most alternative options unavailable in the majority of NHS Trusts. Current evidence supports their role in the management of OSA even though their success rates vary. Guidelines published by the European Respiratory Society, the European Sleep Research Society and many national groups (USA, Canada, Germany, Spain, Finland and India) include mandibular advancement devices and a wide range of surgical techniques in the management of OSA, either as a first-line treatment especially in mild OSA or more commonly as a ‘salvage’ therapy in selected patients after CPAP failure.Reference Mandavia, Mehta and Veer9

Tonsillectomy is recommended in the presence of tonsillar hypertrophy and CPAP failure, whereas soft palate surgery is considered as an option in carefully selected patients. Maxillo-mandibular advancement is recommended in patients with severe OSA and maxillomandibular retrusion when other treatment options fail. Furthermore, the American, German and Spanish guidelines consider tongue base surgery and mainly minimally invasive techniques as an option for OSA management.Reference Aurora, Casey, Kristo, Auerbach, Bista and Chowdhuri16–Reference Lloberes, Duran-Cantolla, Martinez-Garcia, Marin, Ferrer and Corral18 They also suggest nasal surgery to improve airway patency and CPAP compliance in selective patients.Reference Verse, Dreher, Heiser, Herzog, Maurer and Pirsig17–Reference Ishii, Tollefson, Basura, Rosenfeld, Abramson and Chaiet19 In contrast, hypoglossal nerve stimulation as a treatment option for OSA is currently included only in the German guidelines.Reference Verse, Dreher, Heiser, Herzog, Maurer and Pirsig17

Cost-effectiveness of CPAP and alternatives

Continuous positive airway pressure is cost-effective for management of OSA, and its cost-effectiveness is estimated to be below £5000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained.7 Although oral devices are less cost-effective than CPAP, they are still cost-effective compared with no treatment, especially in mild and moderate disease.Reference Sadatsafavi, Marra, Ayas, Stradling and Fleetham20,Reference Quinnell, Bennett, Jordan, Clutterbuck-James, Davies and Smith21 Sleep surgery is also cost-effective in patients with OSA and CPAP intolerance.Reference Tan, Toh, Guilleminault and Holty22 Specifically, palatopharyngeal reconstructive surgery seems to be cost-effective compared with no therapy in middle-aged men with severe OSA intolerant of CPAP. Likewise, hypoglossal nerve stimulation is cost-effective compared with no treatment.Reference Pietzsch, Liu, Garner, Kezirian and Strollo23

Mandibular advancement devices

Oral appliances consist of a heterogenous group of devices aiming to improve upper airway patency and have emerged as a non-invasive alternative to CPAP for the treatment of OSA.Reference Tsai, Vazquez, Oshima, Dort, Roycroft and Lowe24,Reference Schwab, Pasirstein, Pierson, Mackley, Hachadoorian and Arens25 Mandibular advancement devices are the most commonly used and evaluated appliances and increase upper airway diameter by advancing the mandible forward.Reference Marklund, Braem and Verbraecken26 Most clinical commissioning groups do not provide guidance for treatment with mandibular advancement devices, with a minority funding their use in the presence of CPAP intolerance. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance considers mandibular advancement devices as a potential treatment modality for moderate OSA, but uncertainty remains because of insufficient data for their effectiveness compared with CPAP in mild and severe disease.7

Since the last NICE update, there has been growing evidence supporting the role of mandibular advancement devices in patients with OSA. Mandibular advancement devices can be considered effective compared with no treatment in OSA patients and predominantly in those with mild-to-moderate disease with a mean apnoea–hypopnoea index reduction of 30–72 per cent and a cure rate of 45–100 per cent.Reference Quinnell, Bennett, Jordan, Clutterbuck-James, Davies and Smith21,Reference Vanderveken and Hoekema27–Reference Aarab, Lobbezoo, Heymans, Hamburger and Naeije31 On the other hand, because of patients’ discomfort, the compliance ranges between 51 and 88 per cent.Reference Sharma, Katoch, Mohan, Kadhiravan, Elavarasi and Ragesh32 Guidelines from several countries recommend the use of mandibular advancement devices either as the first-line treatment in mild OSA or as an alternative therapy in patients with OSA and CPAP failure.Reference Epstein, Kristo, Strollo, Friedman, Malhotra and Patil10,Reference Sharma, Katoch, Mohan, Kadhiravan, Elavarasi and Ragesh32–Reference Ramar, Dort, Katz, Lettieri, Harrod and Thomas35

Tonsillectomy

Whereas NICE guidelines did not include tonsillectomy in the last update, there are a significant number of clinical commissioning groups considering tonsillectomy as a treatment option for OSA. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Camacho et al. showed that isolated tonsillectomy can be successful for OSA treatment, especially in patients with large, grade 2 to 4 tonsils and mild-to-moderate OSA.Reference Camacho, Li, Kawai, Zaghi, Teixeira and Senchak36 The mean apnoea–hypopnoea index reduction was 65.2 per cent with a success rate of 100 per cent in patients with mild-to-moderate OSA, and the success rate was 72 per cent with a cure rate of 34 per cent in patients with severe OSA. Therefore, tonsillectomy, either as a single operation or in combination with other procedures, could potentially play an important role in adult OSA treatment. Most guidelines worldwide consider tonsillectomy as an option in adults with enlarged tonsils, with or without CPAP incompliance.Reference Mandavia, Mehta and Veer9,Reference Verse, Dreher, Heiser, Herzog, Maurer and Pirsig17,Reference Sharma, Katoch, Mohan, Kadhiravan, Elavarasi and Ragesh32–Reference Fischer, Dogas, Bassetti, Berg, Grote and Jennum34

Soft palate surgery

Several interventions aiming to either increase the integrity of the soft palate or change its shape exist. There has been limited evidence supporting the efficacy of pillar implants;Reference Brietzke and Mair37 therefore, NICE guidelines do not recommend their use in the treatment of OSA.12 Likewise, NICE has approved the use of radiofrequency to the soft palate for treatment of snoring but not for OSA,13 although previous studies have demonstrated good results in OSA patients.Reference Farrar, Ryan, Oliver and Gillespie38 Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) is the most common operation for the treatment of OSA, and a meta-analysis demonstrated that UPPP (with or without tonsillectomy) has success rates between 35 and 95.2 per cent.Reference Stuck, Ravesloot, Eschenhagen, de Vet and Sommer39 Moreover, a randomised controlled trial showed that selective patients undergoing UPPP had up to 60 per cent reduction in apnoea–hypopnoea index compared with those not undergoing surgery,Reference Browaldh, Nerfeldt, Lysdahl, Bring and Friberg40 with sustainable favourable outcomes 24 months post-operatively.Reference Browaldh, Bring and Friberg41 Most guidelines do not recommend laser-assisted palatoplasty because of variable efficacy and complications,Reference Mandavia, Mehta and Veer9 but some authors suggest that a modified technique can be effective.Reference Chisholm and Kotecha42 More recently, expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty has gained popularity and seems to be an effective treatment for OSA patients with lateral wall collapse leading to significant improvement in apnoea–hypopnoea index and a success rate of 86.3 per cent.Reference Pang, Pang, Win, Pang and Woodson43

There is a great variation in the outcomes of palatal surgery associated with a variety of indications and techniques. In most studies, palatal surgery is performed in conjunction with tonsillectomy making it difficult to quantify the effect of palatal surgery over tonsillectomy alone. Nevertheless, Browaldh et al. showed that patients with tonsil size 2, 3 and 4 benefitted similarly from UPPP and tonsillectomy, suggesting that palatal surgery plays a significant role in the outcome.Reference Browaldh, Bring and Friberg41 Palatal surgery for the management of OSA has not been approved by NICE and is only funded by one clinical commissioning group, but the promising results after careful patient selection should be acknowledged.

Tongue base surgery

Tongue base surgery includes minimally invasive techniques such as the use of radiofrequency ablation and more invasive operations such as midline glossectomy. It is currently offered as an option for OSA management by only one NHS trust. A review of 18 articles and 522 patients undergoing three different tongue base surgery techniques showed a reduction of 27.8 per cent in post-operative apnoea–hypopnoea index.Reference Murphey, Kandl, Nguyen, Weber and Gillespie44 Transoral robotic surgery has recently been used to facilitate access to this challenging anatomical area, and the data have been encouraging. Arora et al.Reference Arora, Chaidas, Garas, Amlani, Darzi and Kotecha45 demonstrated an overall 51 per cent reduction in apnoea–hypopnoea index in patients with moderate-to-severe OSA undergoing transoral robotic surgery to the tongue base with a cure rate of 36 per cent. A meta-analysis showed a success rate of 68.4 per cent and a cure rate of 23.8 per cent.Reference Miller, Nguyen, Ong and Gillespie46

Nasal surgery

Nasal surgery alone is rarely an effective treatment for OSA, and thus only a limited number of clinical commissioning groups include this operation in their OSA management policy. However, several studies have shown an association between nasal complaints and decreased CPAP compliance.Reference Sugiura, Noda, Nakata, Yasuda, Soga and Miyata47,Reference Brander, Soirinsuo and Lohela48 A recent study showed that 71 per cent of nasal breathers comply with CPAP use after one year in contrast with only 30 per cent of mouth breathers during sleep.Reference Bachour and Maasilta49 Inoue et al. demonstrated that nasal disease and nasal parameters are important factors for early CPAP therapy discontinuation.Reference Inoue, Chiba, Matsuura, Osafune, Capasso and Wada50 A meta-analysis showed that nasal surgery can reduce CPAP pressure requirements and improve discomfort levels.Reference Camacho, Riaz, Capasso, Ruoff, Guilleminault and Kushida51 For that reason, nasal obstruction should be adequately treated to facilitate CPAP delivery and improve CPAP compliance and effectiveness.Reference Mandavia, Mehta and Veer9

Hypoglossal nerve stimulation

Hypoglossal nerve stimulation is a relatively new treatment modality for OSA patients in which upper airway stimulation is synchronised with inspiration via an electrical implant resulting in improvement of upper airway muscle tone and upper airway patency during sleep. The NICE guidance states that safety and efficacy of hypoglossal nerve stimulation were limited at the time of the report (2017), and it should only be used in special arrangements.14 Over recent years, there has been a growing body of evidence supporting hypoglossal nerve stimulation safety and effectiveness for selective patients with moderate-to-severe OSA, CPAP incompliance and appropriate upper airway anatomy. Hypoglossal nerve stimulation has shown a success rate of 81 per cent with improvement in OSA severity, sleepiness and quality of life.Reference Yu and Thaler52 The rate of serious adverse events was found to be less than 2 per cent.Reference Strollo, Soose, Maurer, de Vries, Cornelius and Froymovich53 Despite its high cost, hypoglossal nerve stimulation seems to be a promising therapeutic option for selective patients.

Mandibular surgery

Mandibular surgery consists of reconstruction of the mandible, and several studies show a high success rate for OSA treatment that is almost comparable with tracheostomy.Reference Faria, Xavier, Silva, Trawitzki and de Mello-Filho54,Reference Hsieh and Liao55 On the other hand, it is an invasive operation altering the facial skeleton which is associated with significant post-operative morbidity and rare but potentially serious complications.Reference Holty and Guilleminault56 For that reason, it is usually preserved as one of the last treatment options.

Conclusion

Despite the uncertainty regarding the optimal treatment strategy for people with OSA and CPAP intolerance, it is evident that leaving them untreated is the least desirable scenario with a significant impact on patients’ morbidity and cost implications for the NHS. Careful patient selection is of key importance to improve outcomes. Alternative therapies should be tailored to selected patients based on upper airway anatomy, collar size and body mass index after taking into consideration available options, possible risks and patients’ individual needs. We believe that the management of OSA patients should move from a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to individualised consideration of the appropriate treatment option for each patient.

Our study shows the presence of remarkable variation in available therapies for OSA across England, demonstrating the need for a review of the current literature and revision of the NICE guidelines. This will assist clinical commissioning groups in developing their policies and will reduce geographical inequity in available therapeutic options for OSA. The patients will obtain access to a range of treatment modalities which will hopefully reduce the number of patients with untreated OSA, subsequently resulting in direct and indirect health benefits for them and cost savings for the NHS.

Competing interests

None declared