Introduction

Total thyroidectomy (removal of the entire thyroid gland) is the treatment of choice for a large proportion of thyroid malignancies and for benign thyroid pathologies such as Graves’ disease and multinodular goitre.Reference Harness, Fung, Thompson, Burney and McLeod1–Reference Haugen, Alexander, Bible, Doherty, Mandel and Nikiforov5 In the UK, around 9000 total thyroidectomies are performed every year, with benign disease accounting for a majority of the cases (Graves’ disease: 31 per cent; toxic multinodular goitre: 29 per cent).Reference Chadwick, Kinsman, Walton and :6

Post-operative hypocalcaemia is a common complication following total thyroidectomy, with an incidence of around 30 per cent.Reference Bhattacharyya and Fried3,Reference Pattou, Combemale, Fabre, Carnaille, Decoulx and Wemeau7–Reference Edafe, Antakia, Laskar, Uttley and Balasubramanian9 Hypocalcaemia is variably defined by measured serum calcium levels, with or without the presence of symptoms and signs. It occurs as a result of inadvertent damage or removal of the parathyroid glands, either directly or indirectly through disruption of the blood supply. Most cases are transient, and calcium levels normalise over a period of months. However, around 2 per cent of patients develop permanent hypoparathyroidism, defined as low serum parathyroid levels or ongoing need for calcium supplementation at 12 months.Reference Edafe, Antakia, Laskar, Uttley and Balasubramanian9,Reference Seo, Chang, Jin, Lim, Rha and Koo10

Although a majority of patients with post-operative hypocalcaemia are asymptomatic, up to 30 per cent may develop symptoms, and a small proportion develop severe hypocalcaemia requiring intravenous calcium supplementation. As well as prolonging hospital length of stay, hypocalcaemia necessitates repeated blood tests and may warrant intensive care unit admission for central line insertion and monitoring if intravenous calcium replacement is required.Reference Grainger, Ahmed, Gama, Liew, Buch and Cullen11,Reference Baldassarre, Chang, Brumund and Bouvet12

Systematic reviews have shown that supplementation with calcium or vitamin D after thyroidectomy reduces the risk of hypocalcaemia.Reference Alhefdhi, Mazeh and Chen13,Reference Sanabria, Dominguez, Vega, Osorio and Duarte14 However, evidence around outcomes following pre-operative supplementation with hypercalcaemic agents remains ambiguous, and there are no systematic reviews or meta-analyses studying this.

This systematic review aimed to establish the evidence behind the use of pre-operative calcium or vitamin D supplementation to prevent post-operative hypocalcaemia in patients undergoing thyroidectomy. We hypothesised that pre-operative treatment with calcium or vitamin D would reduce the incidence of post-operative hypocalcaemia in total thyroidectomy patients. Our secondary aim was to assess whether pre-operative supplementation reduced the length of stay in hospital following total thyroidectomy.

Materials and methods

Inclusion criteria

This review included prospective clinical trials on adult human patients undergoing total thyroidectomy that were published in English and which assessed the effect of pre-operative calcium or vitamin D and its derivatives on the rate of post-operative hypocalcaemia.

Method

PubMed, Embase and Cochrane databases were searched. Search terms used were ‘thyroid’, ‘thyroid surgery’, ‘thyroid removal’, ‘thyroid resection’, ‘thyroidectomy’, ‘vitamin’, ‘vitamin D’, ‘vitamin D3’, ‘vitamin supplement’, ‘calcitriol’, ‘alfacalcidol’, ‘cholecalciferol’, ‘calcium carbonate’ and ‘calcium’. Limits used were ‘English language’ and ‘human subjects’.

Results were initially screened by title and then by abstract. Finally, full papers were examined. Those that met the eligibility criteria were included in the review. Cochrane's risk of bias tool (version 2) was used for quality assessment of the trials included in this review.Reference Sterne, Savović, Page, Elbers, Blencowe and Boutron15

Results

The search identified 5501 articles on PubMed, 6784 articles on Embase and 778 articles on Cochrane. One hundred and twenty-six articles were selected following title screening. Of these, 25 articles selected following abstract screening were examined in full.

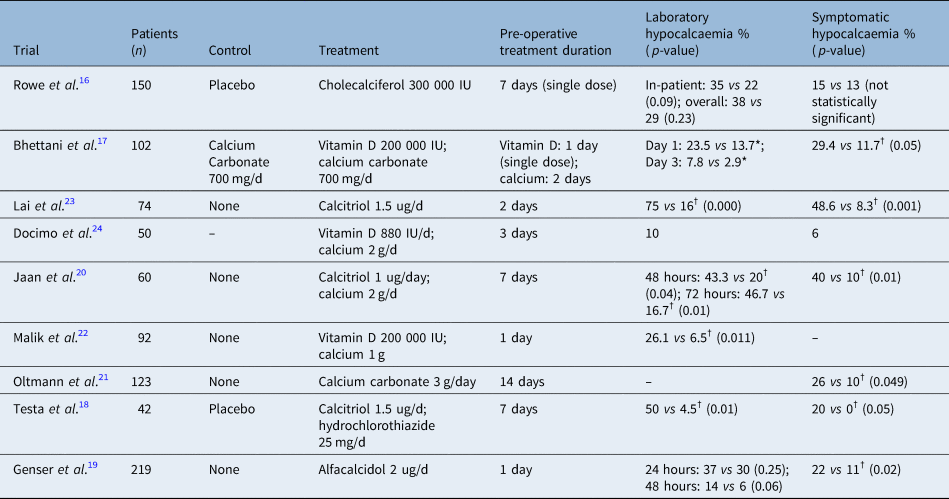

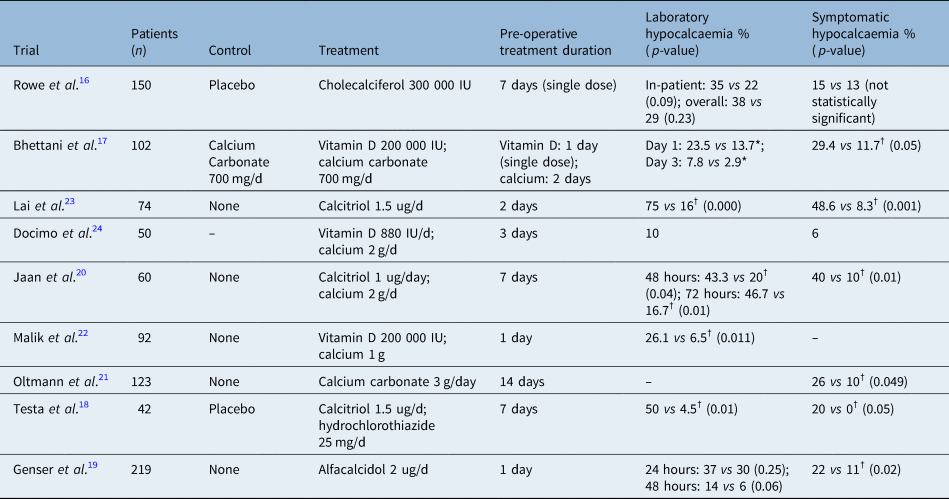

Nine trials met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1 and Table 1).Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16–Reference Docimo, Tolone, Pasquali, Conzo, D'Alessandro and Casalino24 They included a total of 912 patients. The trials were published between 2006 and 2019, spanning 14 years. All nine trials studied adult populations in surgical in-patient departments, with follow up in out-patient clinics. Two trials were based in Italy,Reference Testa, Fant, De Rosa, Fiore, Grieco and Castaldi18,Reference Docimo, Tolone, Pasquali, Conzo, D'Alessandro and Casalino24 two were in PakistanReference Bhettani, Rehman, Ahmed, Altaf, Choudry and Khan17,Reference Malik, Mirza, Farooqi, Chaudhary, Waqar and Bhatti22 and the others were in India,Reference Jaan, Sehgal, Wani, Wani, Wani and Laway20 the USA,Reference Oltmann, Brekke, Schneider, Schaefer, Chen and Sippel21 Malaysia,Reference Lai, Zainira, Imisairi, Mazuin, Mokhzani and Ikhwan23 AustraliaReference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16 and France.Reference Genser, Trésallet, Godiris-Petit, Li Sun Fui, Salepcioglu and Royer19

Fig. 1. Flowchart of search strategy.

Table 1. Summary of included systematic reviews including rates of laboratory and symptomatic hypocalcaemia

*P-value not reported; †statistically significant data.

Six trials studied patients undergoing total thyroidectomy only: one included patients who had near total thyroidectomy,Reference Jaan, Sehgal, Wani, Wani, Wani and Laway20 where less than 1 ml of the thyroid gland is spared excision; one included patients who had completion thyroidectomy (removal of remnant thyroid tissue following less than total thyroidectomy);Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16 and one included patients undergoing near total and subtotal thyroidectomy (sparing 3–5 g of thyroid tissue).Reference Bhettani, Rehman, Ahmed, Altaf, Choudry and Khan17

Indications for surgery included both malignant and benign thyroid disease in eight trials,Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16–Reference Jaan, Sehgal, Wani, Wani, Wani and Laway20,Reference Malik, Mirza, Farooqi, Chaudhary, Waqar and Bhatti22–Reference Docimo, Tolone, Pasquali, Conzo, D'Alessandro and Casalino24 whereas one trial exclusively studied patients with Graves’ disease.Reference Oltmann, Brekke, Schneider, Schaefer, Chen and Sippel21 Follow up ranged between 1 week to 6 months. None of the trials followed up patients for long enough to comment on permanent hypocalcaemia or hypoparathyroidism, defined as low parathyroid hormone levels or need for calcium supplementation at one-year post-surgery.

Rowe et al. treated 72 patients with a single dose of 300 000 IU cholecalciferol 7 days prior to surgery, while 78 patients received placebo.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16 Post-operatively, both groups were treated with calcium, vitamin D or both, based on a standardised protocol. Calcium was measured at baseline, pre-operatively and post-operatively up to 180 days.

There were no statistically significant differences in the rates of hypocalcaemia between the treatment and control groups at 48 hours (22 vs 35 per cent; p = 0.09) or at any point within 180 days (29 vs 38 per cent; p = 0.23). Symptomatic hypocalcaemia rates were also not statistically significantly different (13 vs 15 per cent). There were no significant differences in hospital length of stay, nor on calcium requirement at 6 months.

Bhettani et al. studied 102 patients, 51 of whom were pre-treated with 200 000 IU of vitamin D one day before surgery.Reference Bhettani, Rehman, Ahmed, Altaf, Choudry and Khan17 Both treatment and control groups were given 700 mg/day of calcium carbonate for 2 days pre-operatively. Post-operatively, both groups received vitamin D and calcium for a month. Serum calcium was measured pre-operatively, post-operatively at 24 hours, on post-operative day 3 (if hypocalcaemic) and up to 4 weeks post-operatively.

Serum calcium levels were statistically significantly lower in the control group compared with the treatment group on post-operative days 1, 7 and 30. Symptomatic hypocalcaemia rate in the treatment group (11.7 per cent) was statistically significantly lower than in the control group (29.4 per cent; p < 0.05). Rates of hypocalcaemia in the treatment group were lower compared with the controls on post-operative day 1 (13.7 vs 23.5 per cent) and day 3 (2.9 vs 7.8 per cent), but the statistical significance was not reported.

Testa et al. studied 42 patients, of which 22 patients were treated with calcitriol of 1.5 mcg/day and hydrochlorothiazide of 25 mg/day for 7 days pre-operatively.Reference Testa, Fant, De Rosa, Fiore, Grieco and Castaldi18 In the control group, 20 patients were given placebo. Post-operatively, patients in both groups were given calcium and calcitriol. Serum calcium levels were measured at baseline, on the day before surgery and daily post-operatively.

Pre-treatment with calcitriol and hydrochlorothiazide led to a statistically significant increase in pre-operative serum calcium compared with baseline (2.44 vs 2.34 mmol/l; p < 0.05). No significant difference was seen in the control arm (2.30 vs 2.29 mmol/l). Laboratory hypocalcaemia (serum calcium less than 2.10 mmol/l) was seen in 4.5 per cent of patients in the treatment group compared with 50 per cent of controls (p < 0.01). None of the patients in the treatment group developed symptomatic hypocalcaemia compared with 20 per cent in the control arm. Hospital stay was longer in the control group (3.6 days) compared with the treatment group (2.4 days; p < 0.05).

Genser et al. studied 219 patients, of which 111 were treated with 2 ug of alfacalcidol per day from pre-operative day 1 to post-operative day 8.Reference Genser, Trésallet, Godiris-Petit, Li Sun Fui, Salepcioglu and Royer19 One-hundred and eight controls were not treated. Serum calcium levels were measured pre-operatively, on post-operative day 1 and daily thereafter in hypocalcaemic patients. Calcium supplementation was given to hypocalcaemic patients. Serum calcium was measured at 5 weeks and 6 months post-surgery.

Statistically significant lower calcium levels were seen in the control group (2.04 mmol/l) compared with the treatment group (2.12 mmol/l) on post-operative day 2 but not on post-operative day 1. Rates of hypocalcaemia (serum calcium less than 2 mmol/l) between the two groups on post-operative days 1 or 2 were not significantly different. However, rates of severe hypocalcaemia (serum calcium less than 1.90 mmol/l) (1 vs 6 per cent; p = 0.04) and symptomatic hypocalcaemia (11 vs 22 per cent; p = 0.02) were significantly lower in the treatment group compared with controls. Symptomatic hypocalcaemia was defined by the presence of one of the following: perioral or fingertip paraesthesia, muscle cramps, Chvostek and Trousseau signs, tetany, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and cardiovascular symptoms (not defined). Six months after surgery, hypocalcaemia persisted in four patients in the control arm compared with none in the treatment group (p = 0.04). Hospital length of stay between the two groups was not significantly different.

Jaan et al. studied 60 patients, 30 of whom were treated with 500 mg of oral calcium 4 times daily and 0.25 ug of calcitriol 4 times daily for 7 days prior to surgery and continued for 7 days post-operatively.Reference Jaan, Sehgal, Wani, Wani, Wani and Laway20 The control group of 30 patients received no treatment pre- or post-operatively unless they developed symptomatic hypocalcaemia. Calcium levels were measured pre-operatively and post-operatively for up to 30 days.

Pre-treatment with oral calcium and calcitriol led to no statistically significant differences in post-operative calcium levels between the control and treatment arms. At 24 hours, the rates of hypocalcaemia (serum calcium less than 2.12 mmol/l) were not significantly different between the two groups. However, at 48 hours, hypocalcaemia rate in the treatment arm (20 per cent) was significantly lower compared with controls (43.3 per cent; p = 0.04). This statistically significant difference continued at 72 hours post-operatively, but after 30 days there was no significant difference in hypocalcaemia rates between the two groups. The rate of symptomatic hypocalcaemia was significantly lower in the treatment arm (10 per cent) compared with controls (40 per cent; p < 0.01). Symptomatic hypocalcaemia was defined as the presence of one of the following: perioral or fingertip paraesthesia, neuropsychiatric manifestations, Chvostek and Trousseau signs, and prolonged QT interval on electrocardiogram.

Oltmann et al. studied 123 patients.Reference Oltmann, Brekke, Schneider, Schaefer, Chen and Sippel21 Of these, 45 patients undergoing total thyroidectomy for Graves’ disease were pre-treated with 1 g of calcium carbonate 3 times daily for 2 weeks prior to surgery. Thirty-eight historic controls undergoing total thyroidectomy for Graves’ disease were not pre-treated. Forty patients undergoing total thyroidectomy for a non-Graves’ pathology, who were not pre-treated, acted as procedural controls. Post-operatively, all Graves’ disease patients were routinely given calcium supplementation, whereas use of calcitriol was protocol driven. Calcium levels were measured pre-operatively. In patients staying in hospital overnight, calcium levels were also measured at 4 hours post-operatively. Calcium measurement on post-operative day 1 was at surgeon discretion.

Pre-treatment with calcium carbonate led to a symptomatic hypocalcaemia rate of 10 per cent, compared with 26 per cent in the control arm (p = 0.049). Symptomatic hypocalcaemia was defined as the presence of numbness, tingling, muscle cramping or tetany. Four-hour post-operative calcium levels were significantly higher in the pre-treated group (2.15 mmol/l) compared with controls (2.07 mmol/l; p = 0.05).

Malik et al. studied 92 patients.Reference Malik, Mirza, Farooqi, Chaudhary, Waqar and Bhatti22 Forty-six were treated with 200 000 IU of vitamin D and 1 g of calcium for 24 hours prior to surgery. In the control group, patients were not given anything. Post-operative treatment was not reported. In the treatment arm, 6.5 per cent developed hypocalcaemia (serum calcium <2.12 mmol/l) compared with 26.1 per cent in the control arm (p = 0.011).

Lai et al. studied 74 patients, who received either 0.5 mcg of calcitriol 3 times daily for 2 days pre-operatively or no pre-operative supplement.Reference Lai, Zainira, Imisairi, Mazuin, Mokhzani and Ikhwan23 Post-operatively, patients in the treatment arm were given calcitriol and oral calcium for one week. In the control arm, patients were given neither unless they were symptomatic. Calcium was measured up to 48 hours post-operatively and patients were followed up at 2 weeks and 6 months.

Rate of hypocalcaemia (serum calcium less than 2.1 mmol/l) in the treatment group was 16.7 per cent compared with 75 per cent in the control group (p = 0.000). Symptomatic hypocalcaemia was also statistically significantly lower in the treatment group (8.3 per cent) compared with the control group (48.6 per cent). Serum calcium between the two groups was significantly lower in the control group at 6 hours, 24 hours and 48 hours post-operatively. Post-operative hospital length of stay was shorter in the treatment group compared with the control group (3.92 vs 4.59 days; p = 0.001).

Docimo et al. studied 50 patients pre-treated with oral calcium of 2 g/day and vitamin D of 880 U/day for 3 days before surgery.Reference Docimo, Tolone, Pasquali, Conzo, D'Alessandro and Casalino24 This trial did not have a control arm. Treatment was continued until post-operative day 14. Calcium levels were measured pre-operatively, on post-operative day 1 and then every 24 hours until discharge. Laboratory hypocalcaemia (serum calcium less than 2 mmol/l) occurred in 10 per cent of patients and symptomatic hypocalcaemia in 6 per cent of patients.

Using Cochrane's risk of bias tool (version 2), one trial had low risk,Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16 four were of some concernReference Bhettani, Rehman, Ahmed, Altaf, Choudry and Khan17–Reference Jaan, Sehgal, Wani, Wani, Wani and Laway20 and four had a high risk of bias.Reference Oltmann, Brekke, Schneider, Schaefer, Chen and Sippel21–Reference Docimo, Tolone, Pasquali, Conzo, D'Alessandro and Casalino24 Risk of bias was because of methodological issues around randomisation, concealment, blinding, analysis and reporting.

Discussion

This systematic review included nine trials studying the effect of pre-operative vitamin D, calcium or both vitamin D and calcium supplementation to reduce the rate of hypocalcaemia after total thyroidectomy.

Seven out of the nine trials showed a statistically significant reduction in the rates of laboratory hypocalcaemia, symptomatic hypocalcaemia or both in patients who were pre-treated.Reference Bhettani, Rehman, Ahmed, Altaf, Choudry and Khan17–Reference Lai, Zainira, Imisairi, Mazuin, Mokhzani and Ikhwan23 Absolute risk reduction in the rate of laboratory hypocalcaemia was 13–59 per cent and for symptomatic hypocalcaemia was 11–40 per cent. In the remaining two trials, one did not have a control arm for comparison.Reference Docimo, Tolone, Pasquali, Conzo, D'Alessandro and Casalino24 Post-operative hypocalcaemia rates in pre-treated patients in this trial were comparable to those seen in the treatment arms of the other trials. Finally, Rowe et al. found no statistically significant differences in rates of laboratory or symptomatic hypocalcaemia, although they reported a trend towards reduced hypocalcaemia rates with pre-treatment.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16

Four out of nine trials reported on hospital length of stay.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16,Reference Testa, Fant, De Rosa, Fiore, Grieco and Castaldi18,Reference Genser, Trésallet, Godiris-Petit, Li Sun Fui, Salepcioglu and Royer19,Reference Lai, Zainira, Imisairi, Mazuin, Mokhzani and Ikhwan23 Two of these found statistically significant reduced length of stay in the treatment group,Reference Testa, Fant, De Rosa, Fiore, Grieco and Castaldi18,Reference Lai, Zainira, Imisairi, Mazuin, Mokhzani and Ikhwan23 and two found no difference.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16,Reference Genser, Trésallet, Godiris-Petit, Li Sun Fui, Salepcioglu and Royer19 A longer length of stay in hospital would be explained by the need for calcium infusion in patients in the control arm who developed symptomatic or severe hypocalcaemia. Hospital length of stay should be measured as an outcome in more trials, given that this is rightly cited as being a significant consequence of hypocalcaemia.

The treatments used in the intervention arms of the trials were not identical. However, all trials used a variant of oral vitamin D (calcitriol, alfacalcidol, cholecalciferol or vitamin D, unspecified) or oral calcium or both. Testa et al. used hydrochlorothiazide, a calcium sparing diuretic, in addition to calcitriol.Reference Testa, Fant, De Rosa, Fiore, Grieco and Castaldi18 Three trials used oral vitamin D only,Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16,Reference Genser, Trésallet, Godiris-Petit, Li Sun Fui, Salepcioglu and Royer19,Reference Lai, Zainira, Imisairi, Mazuin, Mokhzani and Ikhwan23 four trials used vitamin D and calciumReference Bhettani, Rehman, Ahmed, Altaf, Choudry and Khan17,Reference Jaan, Sehgal, Wani, Wani, Wani and Laway20,Reference Malik, Mirza, Farooqi, Chaudhary, Waqar and Bhatti22,Reference Docimo, Tolone, Pasquali, Conzo, D'Alessandro and Casalino24 and one trial used calcium only.Reference Oltmann, Brekke, Schneider, Schaefer, Chen and Sippel21Doses of the hypercalcaemic agents were comparable across the trials.

The duration of pre-operative supplementation varied significantly between the trials, which is one of the limitations of this review. Two trials used pre-operative supplementation for one day,Reference Genser, Trésallet, Godiris-Petit, Li Sun Fui, Salepcioglu and Royer19,Reference Malik, Mirza, Farooqi, Chaudhary, Waqar and Bhatti22 two trials used it for two daysReference Bhettani, Rehman, Ahmed, Altaf, Choudry and Khan17,Reference Lai, Zainira, Imisairi, Mazuin, Mokhzani and Ikhwan23 and one trial used it for three days.Reference Docimo, Tolone, Pasquali, Conzo, D'Alessandro and Casalino24 Four trials had supplementation durations of seven days or longer: two for seven days,Reference Testa, Fant, De Rosa, Fiore, Grieco and Castaldi18,Reference Jaan, Sehgal, Wani, Wani, Wani and Laway20 one for two weeksReference Oltmann, Brekke, Schneider, Schaefer, Chen and Sippel21 and one which gave a single loading dose of cholecalciferol seven days before surgery.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16 Two out of these four reported statistically significant increased peri-operative serum calcium levels, which led to reduced hypocalcaemia rates.Reference Testa, Fant, De Rosa, Fiore, Grieco and Castaldi18,Reference Oltmann, Brekke, Schneider, Schaefer, Chen and Sippel21 One reported no significant difference in serum calcium levels but found statistically significant reduced rates of hypocalcaemia in the treatment arm.Reference Jaan, Sehgal, Wani, Wani, Wani and Laway20 In the fourth trial, post-operative serum calcium levels were not reported, and no significant decrease in post-operative hypocalcaemia rates was found.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16

Genser et al. also reported statistically significant increased calcium levels in pre-treated patients compared with controls.Reference Genser, Trésallet, Godiris-Petit, Li Sun Fui, Salepcioglu and Royer19 Of note, they started supplementation on pre-operative day 1 and only noted a statistically significant increase in serum calcium on day 2 post-operatively.

These findings suggest that the reduction in rate of post-operative hypocalcaemia is likely mediated through direct effects on serum calcium levels.

Only two out of nine trials measured vitamin D levels.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16,Reference Genser, Trésallet, Godiris-Petit, Li Sun Fui, Salepcioglu and Royer19 Rowe et al. studied a predominantly Caucasian Australian cohort replete in vitamin D, with a mean pre-supplementation level of 72 nmol/l and no patients with severe vitamin D deficiency (less than 25nmol/l). There was no correlation between baseline vitamin D levels and post-operative hypocalcaemia rates. Loading with 300 000 IU cholecalciferol raised the vitamin D levels in the treatment group from 77 nmol/l to 119 nmol/l but did not lead to a significant pre-operative rise in serum calcium. There was a trend towards reduced hypocalcaemia rate in the treatment group, but this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.09). Post-operative serum calcium levels were not reported.

Genser et al. reported a mean baseline vitamin D level of 54 nmol/l.Reference Genser, Trésallet, Godiris-Petit, Li Sun Fui, Salepcioglu and Royer19 Alfacalcidol of 2 ug, given from pre-operative day one to post-operative day eight, led to statistically significant higher calcium levels (2.12 vs 2.04; p = 0.04). Hypocalcaemia rate was reduced in the pre-treated group (6 vs 14 per cent), but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.06). However, symptomatic hypocalcaemia rate was significantly lower in the treatment group (11 vs 22 per cent; p = 0.02). Vitamin D levels five weeks post-operatively were unchanged from baseline.

Jaan et al. and Bhettani et al. did not measure vitamin D levels in their studies but cited high vitamin D deficiency rates of 83 to 92 per cent within their respective populations.Reference Bhettani, Rehman, Ahmed, Altaf, Choudry and Khan17,Reference Jaan, Sehgal, Wani, Wani, Wani and Laway20 They reported post-operative hypocalcaemia rates of 43 and 23.5 per cent, respectively, in their control groups, comparable to the 38 per cent found by Rowe et al. in their vitamin D replete population.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16

These findings suggest that post-operative hypocalcaemia rates are not related to pre-operative vitamin D levels. However, vitamin D supplementation may be more beneficial in deficient populations compared with populations replete in vitamin D. This needs further investigation.

Post-operative treatment in the two arms varied between the trials. Four trials used uniform post-operative treatment in both arms.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16–Reference Testa, Fant, De Rosa, Fiore, Grieco and Castaldi18,Reference Oltmann, Brekke, Schneider, Schaefer, Chen and Sippel21 Testa et al. gave all patients calcium and calcitriol post-operatively.Reference Testa, Fant, De Rosa, Fiore, Grieco and Castaldi18 They reported an absolute risk reduction of laboratory hypocalcaemia of 45 per cent and symptomatic hypocalcaemia of 20 per cent. Bhettani et al. gave all patients calcium and vitamin D post-operatively.Reference Bhettani, Rehman, Ahmed, Altaf, Choudry and Khan17 They found an absolute risk reduction in symptomatic hypocalcaemia of 18 per cent. They also found a 10 per cent absolute risk reduction in laboratory hypocalcaemia, but the statistical significance was not reported. Oltmann et al. routinely gave all patients calcium post-operatively.Reference Oltmann, Brekke, Schneider, Schaefer, Chen and Sippel21 They reported a 16 per cent absolute risk reduction in symptomatic hypocalcaemia. These changes may be attributed to the differential pre-operative supplementation given in these trials.

Where differential pre-operative supplementation was continued into the post-operative period, it is difficult to ascertain how much of the treatment effect is attributable to pre-operative supplementation rather than differential post-operative treatment. This is especially true of the trial conducted by Genser et al., which only started supplementation one day before surgery.Reference Genser, Trésallet, Godiris-Petit, Li Sun Fui, Salepcioglu and Royer19

Two trials reported hypercalcaemia associated with treatment.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16,Reference Testa, Fant, De Rosa, Fiore, Grieco and Castaldi18 Testa et al. reported hypercalcaemia in 3 of 22 pre-treated patients.Reference Testa, Fant, De Rosa, Fiore, Grieco and Castaldi18 However, all were asymptomatic and did not require treatment. Rowe et al. reported hypercalcaemia in three patients pre-treated with vitamin D, which was not statistically significantly different compared with the control group.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16 Again, none of the patients required intervention.

The effect of pre-operative vitamin D or calcium on post-operative hypocalcaemia reported in these trials is likely to be applicable to the UK population. The mean post-operative calcium levels in the control arms of the trials ranged from 2.03 to 2.19 mmol/l, comparable to post-thyroidectomy calcium levels reported in the UK population (2.07–2.17 mmol/l).Reference Edafe, Prasad, Harrison and Balasubramanian25,Reference Wong, Price and Scott-Coombes26 Furthermore, the majority of patients included in this review underwent either total thyroidectomy or near-total thyroidectomy, which represents a large proportion of thyroid surgery undertaken in the UK.Reference Chadwick, Kinsman, Walton and :6

Of the nine trials, seven were reportedly randomised.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16–Reference Jaan, Sehgal, Wani, Wani, Wani and Laway20,Reference Malik, Mirza, Farooqi, Chaudhary, Waqar and Bhatti22,Reference Lai, Zainira, Imisairi, Mazuin, Mokhzani and Ikhwan23 Three of these adequately described their randomisation process.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16,Reference Genser, Trésallet, Godiris-Petit, Li Sun Fui, Salepcioglu and Royer19,Reference Malik, Mirza, Farooqi, Chaudhary, Waqar and Bhatti22 Three trials used a placebo for the control arm and were double-blinded.Reference Rowe, Arthurs, O'Neill, Hawthorne, Carroll and Wynne16–Reference Testa, Fant, De Rosa, Fiore, Grieco and Castaldi18

Oltmann et al. used historic controls.Reference Oltmann, Brekke, Schneider, Schaefer, Chen and Sippel21 This trial was neither randomised, nor blinded. Baseline differences between the treatment and control groups included the rate of auto-transplantation required during surgery (significantly higher in the study population). Docimo et al. had no control arm, so randomisation and blinding were not applicable.Reference Docimo, Tolone, Pasquali, Conzo, D'Alessandro and Casalino24 This rendered their findings difficult to interpret, and highly susceptible to bias.

Conclusion

Seven out of nine trials identified in this systematic review have shown that pre-operative supplementation with hypercalcaemic drugs (calcium, vitamin D and derivatives or calcium sparing diuretics) reduces the rate of hypocalcaemia. Randomised controlled trials of more robust design and improved standardisation of peri-operative treatment are required before the evidence base can support standardised guidelines in this area. However, the current available evidence suggests that the use of hypercalcaemic drugs in the pre-operative period reduces the number and severity of cases of post-operative hypocalcaemia. Furthermore, none of the trials reported significant side effects from the use of hypercalcaemic drugs, indicating that pre-operative supplementation may provide benefit without conferring increased risk.

Competing interests

None declared