Introduction

Tinnitus is defined as the perception of a sound without an external acoustic source, often described as a perception of ringing, whistling or buzzing in one or both ears.Reference Fioretti, Eibenstein and Fusetti1 Tinnitus affects up to 30 per cent of the adult population, with 6 per cent of these individuals reporting incapacitating symptoms.Reference Heller2 It is important to distinguish between objective tinnitus, which can be generated from vascular, musculoskeletal or respiratory sources, and subjective tinnitus which has a neurophysiological origin.Reference Fioretti, Eibenstein and Fusetti1 Chronic subjective tinnitus is difficult to treat. The aim for most patients who do not achieve symptom resolution is to manage the symptom by tolerating the sensation and minimising its impact on everyday life.Reference Goebel, Kahl, Arnold and Fichter3

It has been hypothesised that tinnitus perception may arise, in part, from increases in spontaneous neural activity in the central auditory system.Reference Kaltenbach4 Benzodiazepines potentiate the inhibition caused by the release of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Hence, if tinnitus is due to auditory central nervous system hyperactivity, then it is likely that benzodiazepines lessen tinnitus symptoms by reducing this hyperactivity through enhancing GABA-mediated inhibition.Reference Han, Nam, Won, Lee, Chun and Choi5 Benzodiazepines are frequently suggested as one of the medication classes for the management of tinnitus, in addition to anticonvulsant agents and anti-depressant medications.Reference Sismanis6, Reference Dobie7

However, benzodiazepines have a significant side-effect profile and, critically, a potential for misuse and abuse. Benzodiazepines contributed to 49 per cent of the total number of drug-related deaths investigated by the Coroners Court of Victoria (Australia) in 2010.8 Benzodiazepines were also the second most common drug involved in ambulance attendances in Victoria, after alcohol, in 2012–2013.Reference Lloyd, Matthews and Gao9 In fact, alprazolam was recently up-scheduled from a schedule 4 (prescription only) to a schedule 8 (drug of dependence) drug category by the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration, in February 2014. This was partly a result of the recognition of its increased morbidity and mortality in overdoses, the evidence of widespread misuse, and the greater diversion from licit sources to illicit use and abuse.10

With such high stakes, it was surprising that no previous systematic review had been conducted to assess the sum of evidence for benzodiazepine use in tinnitus cases. This systematic review aimed to determine the strength of the evidence for benzodiazepine use in tinnitus management and to weigh that against the risks associated with their use, in order to inform future practice.

Materials and methods

This systematic review was registered with Prospero (an international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews) with the registration number CRD42014010772. The databases included in the search, conducted in June 2014, were the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and PsycInfo. The Medical Subject Heading terms used were ‘tinnitus’ and ‘benzodiazepines’ for all databases. The PubMed database had the clinical trial filter applied. All databases were searched using the full historical range. Only articles published in the English language were included. The study design did not necessarily need to be a clinical trial. The population targeted were human subjects reported as suffering from tinnitus; there were no exclusions regarding the method of tinnitus diagnosis. The intervention was required to be a benzodiazepine medication, used for any duration. Interventions included the following specific agents, which are available in Australia: alprazolam, bromazepam, clobazam, clonazepam, diazepam, flunitrazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, nitrazepam and oxazepam.11 For the comparison, it was necessary that at least one other non-benzodiazepine intervention was employed as part of the treatment or that a placebo was used. There were no exclusions based on outcome measures.

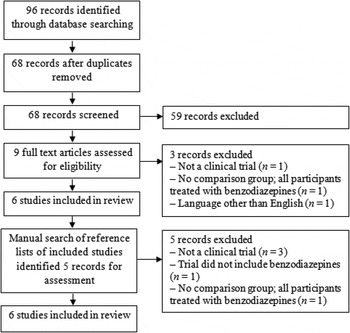

The process of article identification and assessment for eligibility is described in Figure 1.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman12 One investigator completed the screening of the records; however, both investigators reviewed all full text articles independently and discussed any discrepancies until consensus was reached. The assessment of risk of bias of the studies was assessed according to the Cochrane Collaboration tool.Reference Higgins, Altman, Sterne, Higgins and Green13 This assessment and the data extraction were again conducted by both investigators independently, with subsequent discussion regarding any discrepancies.

Fig. 1 Results of literature search presented as a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) flow chart.

Results

There were six studies eligible for inclusion (Figure 1).Reference Han, Nam, Won, Lee, Chun and Choi5, Reference Bahmad, Venosa and Olivieira14–Reference Johnson, Brummett and Schleuning18 All of these studies were randomised trials of at least one benzodiazepine versus a placebo or versus another non-benzodiazepine comparator. An overview of the study designs is shown in Table I.

Table I Studies included in review

VAS = visual analogue scale; mth = months; y = years; wk = weeks; THI = Tinnitus Handicap Inventory; DNS = dose not specified

All studies were assessed for risk of bias; the results are summarised in Table II. At an outcome level, one of the most important domains of risk of bias was blinding of the participants, because of the fact that the outcome measures for tinnitus all contain a degree of subjectivity.Reference Higgins, Altman, Sterne, Higgins and Green13 Three studies reported that the participants were blinded, but did not provide a clear description of this process.Reference Han, Nam, Won, Lee, Chun and Choi5, Reference Bahmad, Venosa and Olivieira14, Reference Lechtenberg and Shulman15 The cross-over design was a feature in four studies,Reference Han, Nam, Won, Lee, Chun and Choi5, Reference Lechtenberg and Shulman15–Reference Jalali, Kousha, Naghavi, Soleimani and Banan17 with two studies not specifying the ‘wash-out’ period (when no active medication was received).Reference Lechtenberg and Shulman15, Reference Kay16 At a study level, the investigations with the least risk of bias across all domains were those by Jalali et al.Reference Jalali, Kousha, Naghavi, Soleimani and Banan17 and Johnson et al.Reference Johnson, Brummett and Schleuning18 At a review level, the overall level of bias is unclear as most of the information is from studies at a low or unclear risk of bias across domains.Reference Higgins, Altman, Sterne, Higgins and Green13

Table II Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The results of the six included studies are shown in Table III. Clonazepam was shown to be effective in treating tinnitus in all three studies in which it was investigated.Reference Han, Nam, Won, Lee, Chun and Choi5, Reference Bahmad, Venosa and Olivieira14, Reference Lechtenberg and Shulman15 The two alprazolam studies showed opposing results.Reference Jalali, Kousha, Naghavi, Soleimani and Banan17, Reference Johnson, Brummett and Schleuning18 Diazepam was shown to not be effective in both studies that investigated it.Reference Lechtenberg and Shulman15, Reference Kay16 Lastly, oxazepam was shown to be effective in the one trial that investigated it.Reference Lechtenberg and Shulman15

Table III Summary of outcomes in included studies

VAS = visual analogue scale; THI = Tinnitus Handicap Inventory

Discussion

This systematic review found six clinical trials of benzodiazepines used in the treatment of tinnitus; these studies employed a number of different agents, with variable results. The results of these trials need to be interpreted in the context of a number of limitations and risks of bias in the study designs.

Tinnitus is a subjective hearing sensation, and as such it is difficult to accurately measure and thereby assess therapeutic results.Reference Aparecida de Azevedo, Mello de Oliveira, Gomes de Siqueira and Figueiredo19 The studies in this review used audiometry, visual analogue scales, the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory, tinnitus loudness assessments and a unspecified self-rating tool to measure the tinnitus sensation of participants. Tinnitus loudness assessments generally involve the participant matching reported tinnitus to externally presented sounds.Reference Basile, Fournier, Hutchins and Hébert20 This method is highly dependent on the participant's intellectual capacity and concentration, and the experience of the assessor.Reference Aparecida de Azevedo, Mello de Oliveira, Gomes de Siqueira and Figueiredo19 In addition, it has been demonstrated that tinnitus loudness does not correlate well with the impact of tinnitus on the participant;Reference Meikle, Vernon and Johnson21 this limits the clinical relevance of this outcome measure. Visual analogue scales are simple to use, which is advantageous. However, the results can be variable; psychosomatic factors in particular can significantly affect tinnitus perception.Reference Kay16, Reference Aparecida de Azevedo, Mello de Oliveira, Gomes de Siqueira and Figueiredo19 The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory has been found to be a valid instrument for use in tinnitus intervention studies.Reference Baguley, Humphriss and Hodgson22 However, there may be problems associated with floor effects; this was suggested as a possible reason for the negative results in one of the included alprazolam trials.Reference Jalali, Kousha, Naghavi, Soleimani and Banan17

Given the subjective nature of tinnitus, a subjective outcome measure will remain a limitation in future studies until such a time when advances in neuroimaging and electrophysiological methods may provide objective measurements.Reference Langguth, Goodey, Azevedo, Bjorne, Cacace and Crocetti23 However, a consensus on a tinnitus outcome measure that could reliably measure the impact on quality of life of tinnitus and fluctuations in severity would facilitate co-operation between research centres and allow more meaningful evaluations and comparison of outcomes.Reference Langguth, Goodey, Azevedo, Bjorne, Cacace and Crocetti23

The reliance on subjective measures for tinnitus assessment highlighted the weakness in many of the studies included in this review. Given the subjective nature of the assessment, it was critical that the participants were blinded to their allocation, and this aspect was not always clearly outlined in the reported methods of the studies. If these studies were inadequate in achieving blinding, then the likely direction of this performance bias is an overestimation of effect.Reference Higgins, Altman, Sterne, Higgins and Green13 Successful blinding was achieved by some studies that used comparators with similar side-effect profiles and no cross-over design, which demonstrates that a superior methodology is possible for future studies.

The cross-over designs may have biased results in subsequent trials, as the participants could have feasibly compared their experience with the previous agent(s) and this might have influenced their perception and experience of their tinnitus. Han et al. presented a cross-over design study where both possible orders of the medications were studied in order to avoid this issue, and the advantage of participants acting as their own controls was retained (thus eliminating the potential for variability in a design associated with a separate control group).Reference Han, Nam, Won, Lee, Chun and Choi5

The treatment regimes in all of the reviewed studies were of short duration, lasting from 4 to 12 weeks. This significantly limits the evidence for benzodiazepine use in cases of chronic subjective tinnitus, which can last for years. This was demonstrated by a temporal population-based study conducted in Australia, where tinnitus persisted after five years in over three-quarters of the cohort.Reference Gopinath, McMahon, Rochtchina, Karpa and Mitchell24 In the study by Johnson et al., which had the longest treatment duration, the authors concluded that benzodiazepines are not appropriate as a long-term measure. Nevertheless, after the conclusion of the trial, some patients experienced tinnitus relief for several weeks before the tinnitus returned to its original level. Furthermore, some patients were able to continue taking the drug at low doses after the trial. However, this data were not presented in the paper. More long-term studies are required to assess the effectiveness of all benzodiazepines as a long-term strategy for this chronic condition.

Benzodiazepines carry a risk of iatrogenic dependence, and have a considerable list of side effects including: sedation or drowsiness (38–75 per cent), memory impairment (up to 15 per cent), unsteadiness, slurring of speech, irritability, mood changes, aggression and reduced motivation.25 Benzodiazepine use is also associated with a significant increase in the risk of traffic accidents.Reference Dassanayake, Michie, Carter and Jones26 The prescription of benzodiazepines should be based on a comprehensive assessment of the patient that identifies a specific diagnostic reason or target symptoms for which good evidence exists for benzodiazepine efficacy.27 Further caution is needed because of the large inter-subject variability in the pharmacokinetics of benzodiazepines,Reference Han, Nam, Won, Lee, Chun and Choi5 which requires individualisation of therapy and slow titration of dosage.

Clonazepam was the benzodiazepine identified in this review with the greatest evidence base for its use in managing tinnitus. Despite the fact that all three studies supported the use of clonazepam, none had adequate reporting of participant blinding, which may have led to overestimation of the results. Interestingly, one of the studies only included participants with a known otological cause of tinnitus (the other studies required participants simply to have the tinnitus symptom);Reference Bahmad, Venosa and Olivieira14 thus, the population in that study was slightly different to that in the other studies. Nevertheless, all three studies yielded positive results.

Clonazepam is a long-acting benzodiazepine with a plasma half-life of 20–40 hours.Reference Howard, Twycross, Shuster, Mihalyo and Wilcock28 This longer half-life reduces the potential for abuse, as shorter half-life drugs have greater dependence potential.Reference O'Brien29 However, it can lead to accumulation when given repeatedly, and undesirable effects may manifest only after several days or weeks, particularly in those with hepatic or renal impairment.Reference Howard, Twycross, Shuster, Mihalyo and Wilcock28

The evidence to support the use of alprazolam in tinnitus was conflicting, with both studies involved having low risk of bias. It is possible that the difference in results is related to potentially different rates of depression or anxiety in the two study groups. The study with the negative result specifically excluded patients who scored positively on the Beck Depression Inventory and Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (with cut-off points of 16 and 14 respectively), or who were diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder in a structured clinical interview conducted by a psychiatrist.Reference Jalali, Kousha, Naghavi, Soleimani and Banan17 The study with positive results did not have this exclusion criteria, although the Beck Depression Inventory was used in the initial assessment.Reference Johnson, Brummett and Schleuning18 The reported results were that only two participants had scores suggestive of mild mood disturbance and all other participants had scores within normal limits.Reference Johnson, Brummett and Schleuning18 It is difficult to compare these two studies with this limited information; however, if the participants in the negative results study had lower rates of depression and anxiety, it is feasible that this partly accounts for the discrepancy in the two studies' results.

Alprazolam is a shorter acting benzodiazepine, with a plasma half-life of 12–15 hours.Reference Howard, Twycross, Shuster, Mihalyo and Wilcock28 A number of studies have reported that people find it difficult to withdraw from alprazolam, with most suggesting that up to half of the recipients are unable to discontinue use within a month.25 In addition, alprazolam causes other adverse reactions including aggression and mood changes, with 10 per cent in one trial becoming hostile while being treated with alprazolam.25

Oxazepam was investigated in only one study. This study had multiple identified risks of bias, particularly regarding the cross-over design and lack of blinding, which limits the reliability of the evidence supporting its use in tinnitus cases.Reference Lechtenberg and Shulman15 Oxazepam has a shorter plasma half-life of 6–20 hours;Reference Howard, Twycross, Shuster, Mihalyo and Wilcock28 however, it does not have the same abuse potential as alprazolam because of its more gradual action onset, which limits the sensation of intoxication immediately after ingestion.Reference Bliding30

Diazepam, with a long half-life of 25–50 hours,Reference Howard, Twycross, Shuster, Mihalyo and Wilcock28 was found to be ineffective in treating tinnitus in both studies where it was investigated. However, this result must be considered in the context of the limitations of the studies, particularly the study by Kay which was not completed because of the effects of another drug in the trial.Reference Kay16

There have been several experimental studies that support the reduction of hyperactivity in the central auditory cortex by GABA-mediated agents. Using single-photon emission computed tomography and the benzodiazepine radioligand 123I-iomazenil, it has been shown that there are diminished benzodiazepine binding sites in the medial temporal lobe cortex of patients with tinnitus of a predominantly central origin.Reference Shulman, Strashun, Seibyl, Daftary and Goldstein31 Receptor binding studies in animal models of tinnitus using long-term salicylate treatment also suggest a decrease in the number of GABAA receptor binding sites in the inferior colliculus.Reference Bauer, Brozoski, Holder and Caspary32

However, there remains the possibility that the effect of benzodiazepines is due to a general anxiolytic effect rather than a direct effect on the neurophysiological cause of tinnitus,Reference Simpson and Davies33 or due to a reduction in neuronal activity by a mechanism not involved in the generation of tinnitus.Reference Darlington and Smith34 It is well known that co-morbid mental disorders, particularly depression and anxiety, are very common in patients with tinnitus.Reference Malakouti, Nojomi, Mahmoudian, Alifattahi and Salehi35 Indeed, in this review, the study by Jalali et al. was the only one that excluded participants with depression or anxiety, and it yielded a negative result.Reference Jalali, Kousha, Naghavi, Soleimani and Banan17

• Chronic subjective tinnitus is difficult to treat; most affected patients should aim for symptom control

• Benzodiazepines have a significant side-effect profile, and potential for abuse and dependence

• Benzodiazepine use for tinnitus does not have a robust evidence base; more long-term trials with less risk of performance bias are needed

• Clonazepam has the most evidence to support its use; it has a long half-life which reduces the potential for abuse, but consideration of other side effects is needed

• Alprazolam has equivocal evidence and a significant side-effect profile; strong consideration of another benzodiazepine or class of drug is recommended

This systematic review excluded clinical trials that did not utilise a non-benzodiazepine comparator. This was considered necessary in order to ensure that the evidence collected on the effectiveness of benzodiazepines in tinnitus was as robust as possible. This criterion led to two studies in particular being excluded during the full text review process.Reference Gananca, Caovilla, Gananca, Gananca, Munhoz and Garcia da Silva36, Reference Shulman, Strashun and Goldstein37 Interestingly, both of these studies examined the effectiveness of clonazepam in tinnitus: one examined clonazepam in combination with gabapentinReference Shulman, Strashun and Goldstein37 and the other (a large retrospective review) examined patients who took clonazepam alone.Reference Gananca, Caovilla, Gananca, Gananca, Munhoz and Garcia da Silva36 Both studies supported the use of clonazepam in tinnitus, which adds further weight to the findings of this systematic review.

Conclusion

Overall, benzodiazepine use in the medical management of subjective tinnitus does not have a robust evidence base. Longer-term trials with less risk of performance bias are needed. Clonazepam has the most evidence to support its use and is relatively less likely to lead to abuse because of its longer half-life, but caution is still needed given the other serious side effects. Diazepam has no evidence to support its use, and alprazolam, which has high abuse potential, has equivocal evidence.