Introduction

Aneurysms are abnormal, localised dilatations of blood vessels and can be classified as either true aneurysms (when all layers of the vessel are involved) or false aneurysms (when an injury to part of the wall causes an abnormal communication with a haematoma outside the wall). The superficial temporal artery is the most common vessel to be involved in the head and neck region.Reference Conner, Rohrich and Pollock1 False aneurysms of the facial artery have been previously documented, but cases of true, spontaneous facial artery aneurysm are extremely rare.

We present a case of a true facial artery aneurysm and briefly discuss the management and related literature.

Case report

A 78-year-old woman presented with a non-tender, palpable, firm lump just below the right side of the mandible. The lump had been steadily increasing in size over a four-week period. There were no upper aero-digestive tract symptoms and no history of trauma or surgery to the head and neck. The patient's past medical history included mild asthma, and she denied any history of tobacco or alcohol use.

Examination confirmed a firm, 2 cm, spherical swelling in the right submandibular triangle, which was non-pulsatile. Intra-oral examination was unremarkable. Endoscopic examination of the nasopharynx and laryngopharynx was also normal.

The provisional diagnosis was salivary gland tumour. However, fine needle aspiration yielded blood only.

A computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1) was requested and demonstrated an aneurysm of the right facial artery just below the mandible, measuring 2.2 cm in diameter. There was calcification of the wall and thrombus formation within the lumen. The external and internal carotid arteries and the surrounding soft tissues were normal.

Fig. 1 Axial computed tomography scan with intravenous contrast, showing the position of the aneurysm, with mural thrombus and wall calcification.

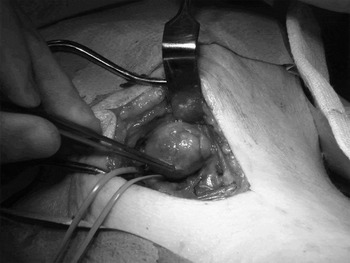

The patient subsequently underwent surgical excision of the aneurysm (Figure 2). An external approach was used, the aneurysm was dissected open and feeding vessels were ligated.

Fig. 2 Intra-operative photograph of the true facial artery aneurysm, with control of the proximal supply.

The post-operative course was uneventful, and the patient was subsequently discharged home.

Discussion

There are a number of reports regarding aneurysms of the extracranial head and neck. The most frequently affected vessels are the superficial temporal arteryReference Buckspan and Rees2 and the facial artery.Reference Aljaro, Maffei and Moriamez3 The vast majority of these cases describe false aneurysms that have an associated traumatic aetiology, including blunt traumaReference Cooperband, Friedel, Bhatt and Eisig4 and penetrating trauma caused by glass,Reference Stewart5 gunshotsReference Germiller, Myers, Harris and Bradford6 and intra-oral prostheses.Reference Tubbs, Kelly, Oakes and Salter7 Injury to the vessel wall gives rise to a local haematoma which expands until the resistance of surrounding soft tissues equals the systolic arterial pressure. Eventually, the adjacent thrombus organises and liquefies to leave a fibrous capsule that is in continuity with the lumen of the vessel.Reference Germiller, Myers, Harris and Bradford6

True aneurysms are a dilatation of the artery wall, involving all three vessel layers (intima, media and adventitia). Causes for true aneurysms include infections (mycotic and syphilitic), congenital abnormalities and, most commonly, atherosclerosis, which was the aetiology in our case.

Reports of true aneurysms of the facial artery are extremely rare, and the management of these lesions is not widely acknowledged. Aljaro et al. Reference Aljaro, Maffei and Moriamez3 reported a case of true facial artery aneurysm which appeared spontaneously in a hypertensive, diabetic patient. They identified the aneurysm using colour Doppler ultrasound and excised the lesion under local anaesthetic. The aneurysm in our case was considerably larger and consequently a general anaesthetic was used. The only other reported case of true facial aneurysm (identified via a Medline search) was presented by Do Carmo Galindo et al., Reference Do Carmo Galindo, Augusto Lima, Galindo Filho, Marcondes Penha and do Carmo Galindo8 who investigated a pulsatile lump using Doppler ultrasound. The lump in our case was non-pulsatile, and this may have been due to extensive calcification of the vessel wall. In addition, the unusual position of the aneurysm and the lack of a supporting history made the likelihood of its diagnosis on purely clinical grounds remote.

The definitive diagnosis was made with the aid of CT. No venous enhancement was seen, making the possibility of an arterio-venous fistula unlikely. Angiography may have been helpful in the investigation of our case, but the CT images gave the necessary diagnostic information for surgical treatment. One advantage of angiography is that it allows for the possibility of endovascular management, such as coiling and embolisation. It has been proposed that false aneurysms be treated primarily with transcatheter embolisation.Reference Lanigan, Hey and West9

• Most facial artery aneurysms have a traumatic aetiology

• True facial aneurysms are extremely rare

• Their management has not been widely discussed in the literature

• This case highlights the need for suspicion of vascular lesions in the head and neck region, even in the absence of clinical features

Conclusion

Most facial artery aneurysms have a traumatic aetiology. If there is no history of trauma, a true aneurysm may be suspected. These are extremely rare and their management has not been widely discussed in the literature. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of a spontaneous true aneurysm of the facial artery which was non-pulsatile at presentation and had no associated risk factors for development. The case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of vascular lesions of the head and neck, as inappropriate investigations and surgery may have serious consequences. This gives further weight to the argument that CT should be an early investigation of choice for head and neck lumps.