Introduction

Pyogenic granuloma is a misnomer because pregnancy tumours do not result from infection or granulomas but rather from lobular capillary haemangiomas.Reference Eversole1–Reference Regezi, Sciubba and Jordan3 In general, pyogenic granulomas manifest as skin lesions; however, they sometimes appear in the oral cavity, nasal cavity or other unusual sites. In the oral cavity, the gingiva is the major involved site, accounting for about 75–85 per cent of oral pyogenic granulomas, followed by the lips, tongue, palate and other unusual sites.Reference Gordón-Núñez, de Vasconcelos Carvalho, Benevenuto, Lopes, Silva and Galvão4–Reference Lawoyin, Arotiba and Dosumu6 Although the mechanism of pyogenic granuloma development is still unclear, oral mucosal micro-trauma, local irritation or poor oral hygiene with accumulated calculus and plaque in the gingival crevice predisposed by angiogenesis-related growth factors are speculated to be the causes.Reference Hamid, Majid and Nooshin7–Reference Yuan, Jin and Lin13 In addition, increased sexual hormonal levels during gestation causing hyperplasic gingivitis sometimes leads to pyogenic granuloma development.Reference Whitaker, Bouquot, Alimario and Whitaker14

Oral pyogenic granuloma developing during gestation, also known as a pregnancy tumour or granuloma gravidarum, accounts for about 10 per cent of all cases.Reference Effiom, Adeyemo and Soyele15 It usually appears in the second to third trimester of gestation and affects about 4–5 per cent of pregnant women.Reference Chamani, Navabi and Abdollahzadeh16, Reference Sills, Zegarelli, Hoschander and Strider17 Because of the associated hormonal imbalance and deteriorating oral hygiene, pregnancy itself is a predisposing factor for the development of pyogenic granulomas.

Histologically, pyogenic granulomas are composed of proliferative capillaries surrounded by inflammatory tissue forming a lobular structure (lobular capillary haemangioma).Reference Eversole1–Reference Regezi, Sciubba and Jordan3 This composition means that easy haemorrhaging and, sometimes, pain are distinguishing features of pyogenic granulomas. Life-threatening massive haemorrhages have been reported.Reference Wang, Chao, Lee, Yuan and Ng18 Pyogenic granulomas range from millimetres to several centimetres in size, but rarely exceed 2.5 cm.Reference Gordón-Núñez, de Vasconcelos Carvalho, Benevenuto, Lopes, Silva and Galvão4, Reference Saravana5, Reference Bouquot, Nikai and Gnepp19 They usually reach their full size within weeks or months.Reference Gordón-Núñez, de Vasconcelos Carvalho, Benevenuto, Lopes, Silva and Galvão4, Reference Saravana5 Large pyogenic granulomas can cause difficulty in eating, nutritional problems and anxiety.

We report the case of a pregnant woman with a large haemorrhagic mandibular gingival pyogenic granuloma. Transarterial micro-embolisation was performed for treatment postpartum. Because the oral lesion shrunk soon after embolisation and had nearly disappeared after a month, no further surgical excision was needed. After following the patient for one year, no recurrence or complications were observed.

Case report

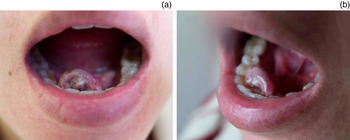

A 33-year-old woman at 34 weeks of gestation had suffered from a progressive tumour of the floor of the mouth for about one month. She presented to the emergency room with massive oral haemorrhaging after brushing her teeth in the morning. Hypovolemic shock was controlled and drowsy consciousness recovered after fluid resuscitation and blood transfusion. On examination, an exophytic, sessile tumour with obvious pulsation and mild tenderness arising from the lingual side of right paramedian mandible sized about 2 × 1.5 × 1.5 cm was noted (Figure 1). At the ventral side of the tumour, there was an ulcerative wound with a tendency to bleed easily. Supportive care with wet gauze to compress the wound was adopted to prevent further haemorrhaging.

Fig. 1 (a, b) A 2 × 1.5 × 1.5 cm exophytic tumour arising from the lingual side of the right paramedian mandible with an ulcerative wound at the ventral side. The tumour mass with obvious pulsation was haemorrhagic and had mild tenderness.

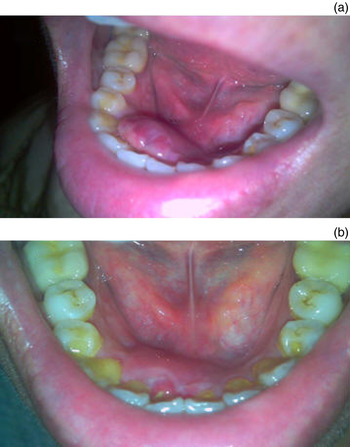

The tumour remained postpartum without a reduction in size. Magnetic resonance angiography performed after childbirth showed a well-defined nodule in the right side of the floor of the mouth with hypointensity on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging. The tumour was enhanced heterogeneously after the intravenous injection of gadolinium contrast medium (Figure 2). Because of its relatively large size and easy bleeding tendency, transarterial embolisation was arranged before surgical excision. Digital subtraction angiography of the right external carotid and lingual arteries revealed an ill-defined hypervascular tumour stain supplied by the right lingual artery with budding capillaries at the end forming a reticular patch associated with pseudoaneurysm formation (Figure 3). After super-selective catheterisation into the lingual artery, a 20 per cent n-butylcyanoacrylate mixture prepared with 0.5 ml n-butylcyanoacrylate (Ingenor, Gennevilliers, France) and 2.0 ml ethiodised oil (Lipiodol Ultra Fluid; Guerbet, Aulnay-sous-Bois, France) was infused for embolisation. Complete obliteration of the tumour stain as well as the pseudoaneurysm was confirmed by angiography immediately following embolisation. Dental scaling was arranged to improve oral hygiene. After embolisation, the lesion shrunk quickly without further haemorrhaging, and the lesion had disappeared nearly one month later. Thus, no further surgical excision was needed. This patient was followed for one year at our out-patient department, and no recurrence or complications were observed (Figure 4).

Fig. 2 Magnetic resonance imaging scans revealing a nodule on the right side of the mouth floor that was hypointense on T1-weighted imaging (a), hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging (b) and enhanced heterogeneously by contrast medium (c).

Fig. 3 Digital subtraction angiography, showing (a) an anterior posterior projection and (b) a lateral projection. Angiography of the right common carotid system showing a hypervascular tumour stain in the right side of the floor of the mouth with multiple capillaries forming a reticular structure (arrowhead). A concomitant pseudoaneurysm was also present. (c) Angiography of the right lingual artery through a microcatheter showing the budding capillaries forming a lobular architecture associated with a pseudoaneurysm at the tip (arrowheads).

Fig. 4 (a) One week after embolisation, the lesion had shrunk without further haemorrhage or pain. (b) One month after embolisation, the lesion had almost resolved leaving a small prior traumatic wound.

Discussion

In general, pyogenic granuloma management depends on symptom severity and the patient's condition, especially for pregnant women. If the lesion is small, painless and free of haemorrhaging, only supportive care, close observation and follow up is advised.Reference Greenberg and Glick20 On the other hand, surgical excision with the removal of irritants (calculus, plaque and trauma source) is traditionally the first treatment choice. However, in some cases, the lesion may be very large or in a surgically difficult area. Choosing an appropriate alternative is important, especially for pregnant women. The recurrence rate is reported to be up to 14–16 per cent,Reference Krishnapillai, Punnoose, Angadi and Koneru21, Reference Taira, Hill and Everett22 which is higher than for other focal reactive oral lesions.Reference Effiom, Adeyemo and Soyele15 Incomplete excision, failure to remove aetiological factors or re-injury of the area is speculated to be the cause.Reference Regezi, Sciubba and Jordan3

Excision of a large lesion can cause marked deformity, and reconstruction with local flap wound coverage is sometimes performed.Reference Oliveira, Greghi, Taveria, Santos, Machado and Silva23, Reference Nemcovsky, Moses and Artzi24 Post-operative wound pain and the wound infection risk are also disadvantages of surgical intervention. Other treatment modalities such as CO2 laserReference Lindenmüller, Noll, Mameghani and Walter25, neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (‘Nd:YAG’) laser,Reference Hammes, Kaiser, Pohl, Metelmann, Enk and Raulin26, Reference Powell, Bailey, Coopland, Otis, Frank and Meyer27 flashlamp pulsed dye laserReference Meffert, Canga and Meffert28, Reference Khandpur and Sharma29 and cryosurgeryReference Ishida and Ramos-e-Silva30 have been proposed owing to their lower haemorrhage rates and alleviation of thermal injury. However, for larger lesions these treatment modalities can still cause scarring or deformities; difficultly surgical areas also limit their application. In addition, repeated treatments are usually necessary.Reference Hammes, Kaiser, Pohl, Metelmann, Enk and Raulin26 Because of the limitations of surgical excision, intra-lesion injection with absolute ethanol,Reference Ichimiya, Yoshikawa, Hamamoto and Muto31 sodium tetradecyl sulphate,Reference Moon, Hwang and Cho32 monoethanolamine oleateReference Matsumoto, Nakanishi, Seike, Koizumi, Mihara and Kubo33 (for sclerotherapy) or corticosteroidsReference Parisi, Glick and Glick34, Reference Adenis-Lamarre, Fricain, Tabrizi, Turlure, Milpied and Beylot-Barry35 is proposed to be a better alternative because of its simplicity and lack of scarring. However, this minimally invasive method usually requires stepped, repeated interventions for complete treatment.

• A large pyogenic granuloma can cause difficulty in eating, nutritional problems and anxiety

• Surgical excision is limited because of the risks of marked deformity or incomplete excision

• In this unusual case, a giant haemorrhagic pregnancy tumour was controlled by micro-embolisation without further surgical excision

To the best of our knowledge, only a few articles have discussed embolisation for treating very large haemorrhagic pyogenic granulomas. In general, transarterial embolisation is used to treat large oral vasculopathies such as arteriovenous malformation, pseudoaneurysm, haemangioma or other unusual vascular malformations.Reference Loureiro, Falchet, Gavranich and Lobo Leandro36–Reference Kumar, Malik and Kumar40 In this case, the relatively larger size, haemorrhagic tendency and a sessile base without a distinct margin limited the use of surgical excision because of the risk of incomplete excision, wound bleeding and marked deformity. We adopted micro-embolisation for pre-operative management; however, no further surgical excision was needed owing to obvious shrinkage of the oral lesion within a short period and because the lesion almost disappeared after one month. The patient was free from wound pain, infection risk and discomfort when eating. A good prognosis without scar formation and healthy periodontal mucosa was made at follow up.

Conclusion

Adequate management is important for treating pyogenic granulomas; this should be based on lesion size, location and severity, and on the patient's condition, especially for pregnant women. In unusual cases of a giant haemorrhagic pregnancy tumour, micro-embolisation with or without subsequent surgical excision after clinical evaluation can be a safer, more comfortable alternative with a good prognosis.