Introduction

Mastoid exploration remains a common, advanced operation in otolaryngology. Surgery requires a comprehensive understanding of complex anatomy to ensure the complete removal of middle-ear disease and the avoidance of injury to critical structures.Reference Duckworth, Silva, Chandler, Batjer and Zhao1 Although endoscopic approaches are increasingly being adopted, experience of and competence in the established approach using a microscope are still required of otolaryngology trainees for the completion of surgical training programmes.Reference Pollak2,Reference Fonseca and Bento3 Whilst simulation training using cadaveric specimens, virtual reality simulators or three-dimensional print models teach incremental temporal bone dissection safely, exposure, fidelity and realism can be compromised.Reference Duckworth, Silva, Chandler, Batjer and Zhao1,Reference Kashikar, Kerwin, Moberly and Wiet4

Mastoid exploration has one of the steepest learning curves amongst otolaryngology operations. In order to demonstrate this learning curve, performance increments can be matched against validated assessment tools and post-operative outcomes. Higher surgical trainees within the UK have reported their competency scores for modified radical mastoidectomy as being the lowest amongst all operations in their first year of training, only reaching close to full competence at programme completion.Reference Bath and Wilson5

Competency achievement throughout training programmes has been subject to pressure from limited pre-training surgical exposure and a reduction in total training time over the past 25 years. The more individual nature of mastoid exploration, compared to open head and neck surgery, as well as pressures on operating theatre time, may also contribute to limitations in operative exposure and competency attainment. This is reflected in other otological operations. An assessment of training opportunities has reported a reduction from 34.2 per cent of all myringoplasties performed by trainees, to 16 per cent in a similar unit four years later after the introduction of Calman training.Reference Hilmi, Bolton, Ahsan and Nunez6 Higher surgical training itself follows from a period of core surgical training. Otolaryngology trainees in the UK typically manage to attend the recommended three operating sessions (one as primary assistant) per week in only 32.9 per cent of training posts.7

Alongside these issues have been general debates on the role of surgical trainees in performing advanced surgery. In the UK, greater emphasis is being placed on surgical outcomes and complication rates, demonstrated in the publication of department- and surgeon-specific data in these fields. This, and growing demands for surgical services to be consultant-led and consultant-delivered, may lead to conflicts of interest arising between adequate training, good outcomes for patients and the need for consultants to maintain their own skills.

However, studies assessing outcomes and complication rates following bowel, oesophageal, gastric and pancreatic resections have failed to demonstrate increases in morbidity and mortality when trainees undertake part or all of the operation under supervision.Reference Paisley, Praseedom, Madhavan, Garden and Paterson-Brown8–Reference Renwick, Bokey, Chapuis, Zelas, Stewart and Ricard12 Equivalent complication rates have also been demonstrated.

The nature of otological surgery makes close supervision of trainees challenging, and as such junior trainees can encounter difficulties in gaining operative experience compared to more senior colleagues. Our department performs a considerable volume of mastoid exploration surgery for a small unit. We compared the outcomes and complication rates in cases undertaken solely by consultants with those performed by junior trainees under consultant supervision.

Materials and methods

A retrospective review was conducted of case and operation notes between June 2009 and June 2020, including revision operations and cases where bilateral surgery was performed. The operations included: cortical mastoidectomy, atticotomy, atticoantrostomy, modified radical mastoidectomy, combined-approach tympanoplasty and revision mastoidectomy. The principal operator was recorded, as was the extent of the trainees’ involvement. The complications assessed included facial nerve palsy, labyrinth injury and dead ear. Disease recurrence and its time to development were also assessed.

The chi-square test was used to calculate confidence intervals for complication rate and recurrence frequency, with p-values of less than 0.05 being deemed significant.

Results

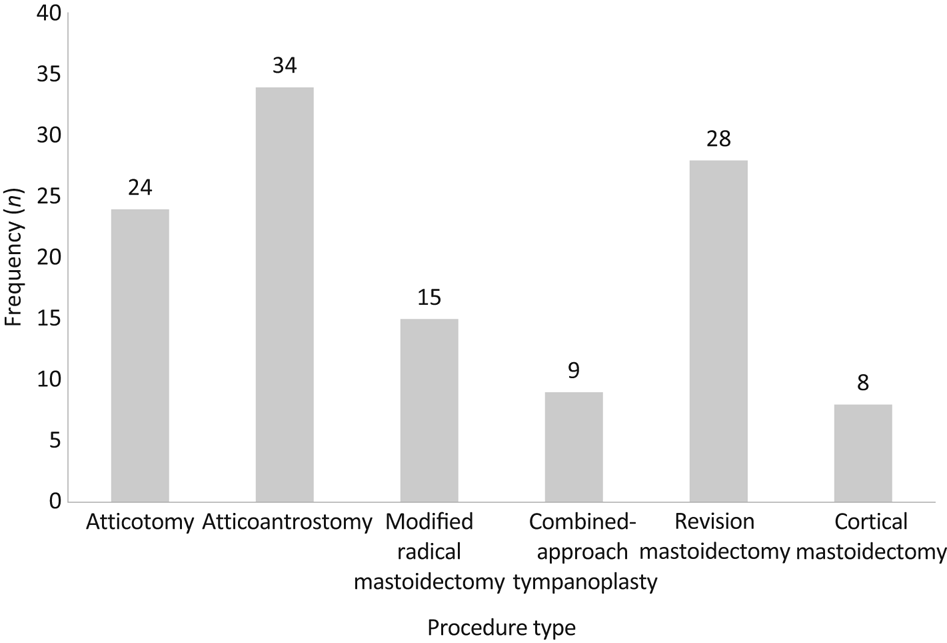

A total of 118 operations were performed between June 2009 and June 2020. Thirteen of the patients were aged under 16 years at the time of surgery. Follow-up duration ranged from 0 months to 11 years (mean of 4.2 years, median of 4.2 years). The numbers of each type of mastoid exploration procedure performed are reported in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Numbers of mastoid exploration procedures performed by type.

Thirty-five per cent of operations (n = 41) were performed by trainee otolaryngologists under supervision, and 65 per cent (n = 77) were carried out solely by consultants. The operations were performed by 14 trainees (trainees performed 1–8 operations) and 5 consultants (performing 1–58 operations).

The overall recurrence rate was 6.8 per cent. Five per cent of operations performed by trainees under supervision (n = 2) developed recurrence, compared with 7.8 per cent performed by consultants (n = 6) (p = 0.55). No facial nerve or labyrinthine injuries occurred, and no patients developed dead ears (Figure 2). One recurrence occurred within the paediatric population (7.7 per cent).

Fig. 2. Numbers of operations, recurrences, complications and team members, for trainees versus consultants.

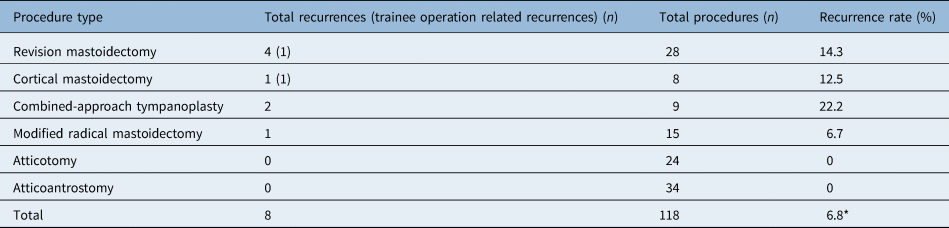

Cholesteatoma recurred after: revision mastoidectomy, in four cases; combined-approach tympanoplasty, in two cases; cortical mastoidectomy, in one case; and modified radical mastoidectomy, in one case (Table 1). The mean duration between surgery and recurrence was 40 months (range, 17–71 months). There were no recurrences for those who underwent atticotomies or atticoantrostomies.

Table 1. Recurrence rate per procedure

*Overall recurrence rate

Discussion

This study's findings corroborate previous research in finding no significant differences between operations performed by trainees and consultants over a prolonged time period. Hassan et al. reported that trainees performing thyroidectomy under close supervision demonstrated no difference in their outcomes compared with their supervisors’ operations.Reference Hassan, Koller, Kluge, Hoffmann, Zielke and Rothmund13 Similar outcomes have been reported for septoplasty and sphenopalatine artery ligation with regard to revision and re-bleed rates respectively.Reference Karlsson, Shakeel, Al-Adhami, Suhailee, Ram and Ah-See14,Reference Hey, Koo Ng and McGarry15 Mahendran et al. reported that post-operative symptoms following tympanomastoid surgery did not vary largely between consultant and otolaryngology trainees at each year of their training.Reference Mahendran, Bennett, Jones, Young and Prinsley16 Vartiainen reported a recurrence rate of 32 per cent for residents compared to 19 per cent for consultants, but that was similarly statistically insignificant, despite larger numbers and an overall recurrence rate of 20 per cent.Reference Vartiainen17

• Multiple studies have shown no increase in complications when operations are performed by trainees

• There have been multiple changes to otolaryngology training over the last two decades

• This study found no difference in complication rates for mastoid surgery

• The procedures assessed included: cortical mastoidectomy, atticotomy, atticoantrostomy, modified radical mastoidectomy, combined-approach tympanoplasty and revision mastoidectomy

• Trainees may be involved preferentially in less complicated procedures

• There is no compromise to patient safety when incorporating trainees in a stepwise manner

There were some drawbacks to this study. Inherent bias likely exists towards trainees completing less complicated cases or simpler components of the operation. Whilst trainees’ competence does not match that of their supervisors, their incorporation in the operative process reinforces their technical skills, particularly in cases of complex disease and aberrant anatomy. We defined trainee involvement as taking part in both drilling and dissecting middle-ear disease. This allows the outcome measures of this study to be partly attributed to the otolaryngology trainee as an operating surgeon. Further trends may exist, such as a competence distribution over time, as described by Mahendran et al.Reference Mahendran, Bennett, Jones, Young and Prinsley16 Comparisons of hospital stay and operating time were not undertaken, as they were assumed to be equivocal. Operating times for trainees are estimated to be 34 per cent longer across specialties.Reference Aitken18 Prolonged operations could make patients more likely to be admitted overnight.Reference Rowlands, Harris, Hern and Knight19 Consultant availability to supervise trainees depends on their own clinical commitments, which in turn can be subject to pressures.Reference Majed, Riaz, Das-Purkayastha, Martin and Gregg-Smith20

Subspecialisation in otology has affected training. Stapedectomy exposure has reversed in North America, from less than 10 per cent of trainees not performing the operation in 1970 to only 10 per cent performing this by completion of training in 2020, despite it being considered a core operation.Reference Ruckenstein and Staab21 Mastoid surgery ranks in the joint highest area of otolaryngology associated with negligence claims.Reference Navaratnam, Hariri, Ho, Machin, Briggs and Marshall22

The current guidelines for the completion of training to a consultant level in the UK state a minimum of 10 mastoid operations as principle surgeon; this is the mean number at which trainees become competent at the steps common to all mastoidectomies, and represents a consensus threshold from training programme directors.23,Reference Carr24 This remains significantly less than the 25 operations associated with a plateau of the learning curve, leaving further training and competence to be attained during independent practice.Reference Fischer, Zehlicke, Gey, Rahne and Plontke25 Adequate distribution of practice sessions is essential to increase future performance, through optimal retention and the sequential building of skills learnt at each stage.Reference Moulton, Dubrowski, Macrae, Graham, Grober and Reznick26,Reference Shea, Lai, Black and Park27

The landscape of otological training in the UK will continue to change with the rise of endoscopic-assisted procedures, likely to be increasingly utilised in the treatment of cholesteatoma.Reference Kanona, Virk and Owa28,Reference Baruah, Lee, Pickering, de Wolf and Coulson29 Endoscopic ear surgery experience may benefit future trainees, as such individuals could more readily transfer previous endoscopic skills, and be better able to adapt from the beginning to lower depth perception and wider camera angles.Reference Pothier30

Conclusion

The future likely holds as many changes in otological surgical training as the preceding two decades. Across many operations, including mastoid surgery, trainee involvement in advanced operations yields no increased risk in the form of complications or recurrences.

Competing interests

None declared