Introduction

Acquired perilymphatic fistula, which consists of an abnormal communication between the inner-ear fluids and the middle-ear space, is one of the most challenging problems in otological practice.Reference Podoshin, Fradis, Ben-David, Berger and Feiglin1 There is no universally accepted diagnostic technique, and this entity is often missed.Reference House, Morris, Kramer, Shasky, Coggan and Putter2, Reference Herman, Guichard, Van den Abbeele, Tan, Bensimon and Marianowski3 Pneumolabyrinth is the condition in which the vestibule or cochlea is filled with air. The presence of air inside the inner ear is definite proof of a pathological connection between the inner ear and the air-filled mastoid or middle-ear cavities.Reference Gross, Ben-Yaakov, Goldfarb and Eliashar4 Pneumolabyrinth and stapes luxation detected by computed tomography (CT) should be proof of perilymphatic fistula. We report a case of post-traumatic perilymphatic fistula, in which pneumolabyrinth with stapediovestibular dislocation was apparent on CT scanning.

Case report

While a 72-year-old woman was scratching her left ear with the shaft of a comb, she hit the comb against an opening door. Immediately after this episode, she experienced vertigo and vomiting.

On admission to our hospital, she had horizonto-rotatory gaze nystagmus, beating to the right. Otoscopic examination detected a small perforation in the posterior half of the tympanic membrane.

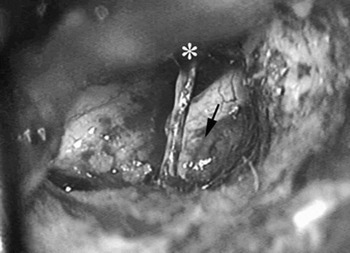

A pure tone audiometric examination detected a mixed-type hearing loss of 58.3 dB with slightly increased bone conduction of 26.7 dB in the left ear. A fistula test was performed and was negative. Computed tomography scanning demonstrated that the stapes was dislocated from the oval window and depressed into the vestibule (Figure 1). A pneumolabyrinth was also evident.

Fig. 1 Computed tomography scans: (a) axial image; (b) axial image 1 mm superior to (a); and (c) coronal image. Black arrows indicate the foot plate of the stapes in the vestibule. White arrows indicate air in the vestibule.

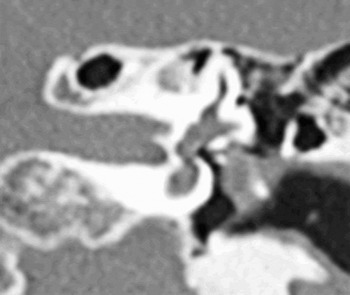

Four days after admission, the patient's mixed-type hearing loss progressed to 76.7 dB with bone conduction of 26.7 dB, and she finally consented to exploratory tympanotomy. After elevating the eardrum, the round window niche was normal. When the ossicles were inspected, the stapes was slightly depressed into the vestibule (Figure 2) and the incudostapedial and incudomalleolar joints were hypermobile. Perilymph was observed to be oozing from the oval window. The stapes was gently drawn back from the vestibule and left in its place. The oval window was sealed with temporalis muscle fascia, which was also used to close the tympanic membrane perforation. Because neither an atticotomy nor a mastoidectomy was performed in our patient, the ossicular chain was reconstructed within the mesotympanum. The incus was removed, trimmed and interposed as a columella between the head of the stapes and the malleus handle.

Fig. 2 Intra-operative view. Black arrow indicates the stapes depressed into the vestibule. White asterisk indicates the chorda tympani.

The day after the operation, the patient's vestibular symptoms completely disappeared. Post-operative CT scans demonstrated the disappearance of the pneumolabyrinth and correct positioning of the stapes and columella (Figure 3). However, hearing loss persisted at 76.7 dB with slightly increased bone conduction of 38.3 dB, six months after surgery.

Fig. 3 Coronal computed tomography image after surgery. The air bubble in the vestibule has disappeared, and the columella and soft tissue are situated lateral to the head of the stapes, which has been set in its correct position.

Discussion

Luxation of the intact stapes out of the window or down into the vestibule is extremely rare.Reference Choe, Arigo and Zeifer5–Reference Yamasoba, Amagai and Karino8 The two main reasons for this rarity are the annular ligament, which firmly attaches the stapes to the oval window, and the housing of the stapes in the deep portion of the tympanic cavity.Reference Meriot, Veillon, Garcia, Nonent, Jezequel and Bourjat6, Reference Bartlett9 A recent review of 166 patients with ossicular injuries demonstrated only five cases of stapediovestibular dislocation.Reference Meriot, Veillon, Garcia, Nonent, Jezequel and Bourjat6 The stapes had prolapsed into the vestibule in only three of these cases. High resolution CT with thin, overlapping slices is the imaging modality of choice, as it can show the depressed stapes in the vestibule.Reference Herman, Guichard, Van den Abbeele, Tan, Bensimon and Marianowski3, Reference Sarac, Cengel and Sennaroglu7, Reference Yamasoba, Amagai and Karino8 Disruption of the stapediovestibular joint may be predictive of a perilymphatic fistula.

Pneumolabyrinth is a condition in which the vestibule or cochlea is filled with air.Reference Gross, Ben-Yaakov, Goldfarb and Eliashar4 The presence of air inside the inner ear is definite proof of a pathological connection between the inner ear and the air-filled mastoid or middle-ear cavities.Reference Gross, Ben-Yaakov, Goldfarb and Eliashar4 Air inside the inner ear is uncommon, but traumatic temporal bone fracturesReference Gross, Ben-Yaakov, Goldfarb and Eliashar4 or fracture of the stapes footplateReference Mafee, Valvassori, Kumar, Yannias and Marcus10 may allow air to enter the vestibule. Other possible causes are spontaneous fistula in cases without a history of trauma,Reference Pashley11 and displacement of a stapes prosthesis after stapes surgery.Reference Scheid, Feehery, Willcox and Lowry12 However, reports of pneumolabyrinth caused by stapediovestibular dislocation are rare. A search of the international literature found only two reported instances.Reference Choe, Arigo and Zeifer5, Reference Sarac, Cengel and Sennaroglu7

• This is a case report of a perilymphatic fistula pre-operatively predicted by computed tomography (CT) findings

• Two previous cases of stapediovestibular dislocation with pneumolabyrinth have been reported in the world literature

• The authors recommend that patients with suspected perilymphatic fistula of traumatic origin undergo high resolution CT of the temporal bone with thin sections

There is no agreed treatment protocol for these cases, due to the limited number of cases with stapediovestibular dislocation.Reference Sarac, Cengel and Sennaroglu7 The condition of the stapes is the key factor determining how surgery should be performed.Reference Sarac, Cengel and Sennaroglu7, Reference Yamasoba, Amagai and Karino8, Reference Arragg and Paparella13 When the stapes is only slightly depressed into the vestibule, reconstruction with or without removal of the stapes has yielded fairly good post-operative hearing results.Reference Arragg and Paparella13 When the stapes is deeply depressed into the vestibule, the risk of causing additional inner-ear damage during surgical intervention is increased.Reference Sarac, Cengel and Sennaroglu7, Reference Yamasoba, Amagai and Karino8 However, leaving a deeply depressed stapes can cause scarring which may fill the vestibular spaces, causing late inner-ear damage.Reference Herman, Guichard, Van den Abbeele, Tan, Bensimon and Marianowski3 Despite the potential risk of additional inner-ear damage, it is better to remove the depressed stapes from the vestibule as soon as possible, before fibrotic bands develop.Reference Sarac, Cengel and Sennaroglu7 In our case, restoration of the stapes to its place together with ossiculoplasty were performed, but hearing loss did not alter, although there was a slight deterioration of bone conduction thresholds.

Conclusion

The detection of pneumolabyrinth with stapediovestibular dislocation is predictive of a perilymphatic fistula. High resolution CT with thin sections may facilitate an accurate diagnosis in cases of suspected perilymphatic fistula, as evidenced by the relationship we found between our patient's CT and surgical findings.