Introduction

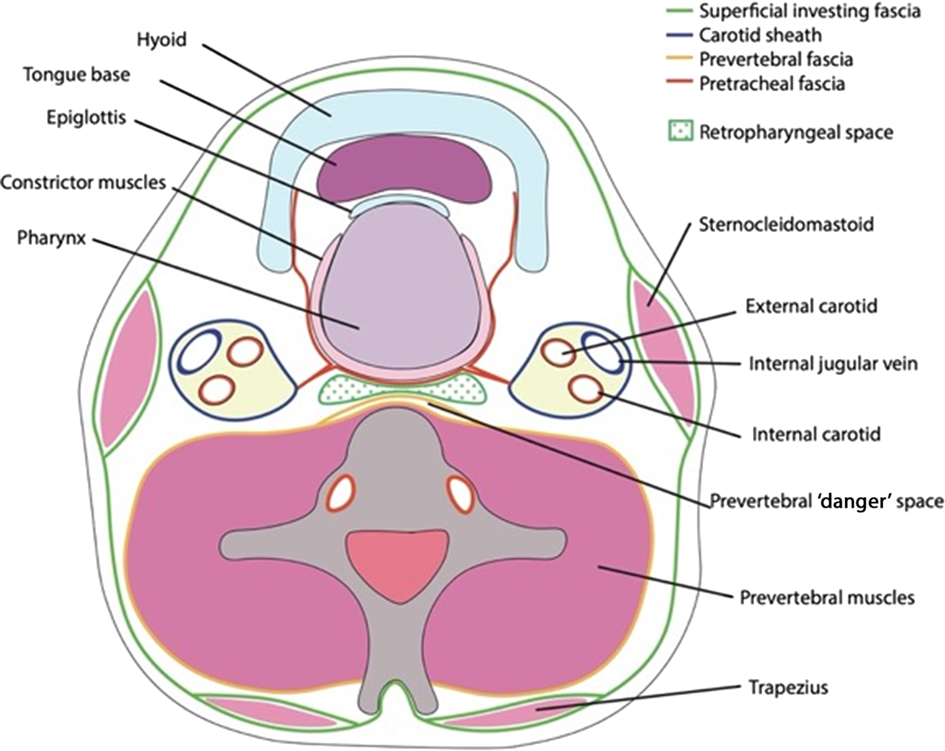

Retropharyngeal haematomas are most often attributed to cervical trauma. Other documented causative factors include anti-coagulation, haemorrhagic transformation of neoplastic lesions, instrumentation, haemophilia, and sudden pressure increases such as when vomiting, coughing or sneezing.Reference Thomás, Torres, García-Polo and Gavilán1–Reference Yamamoto, Schmidt-Niemann and Schindler6 These haematomas occur in the retropharyngeal space – the potential space of loose connective tissue between the middle and deep cervical fascial layers, extending from the skull base to the third thoracic vertebra, where these layers fuse (Figure 1).Reference Pfeiffer and Ridder7 Retropharyngeal haematomas can be life-threatening in cases of: severe infection, disturbance of the swallowing mechanism or airway compromise at the laryngeal inlet.

Fig. 1. Diagram demonstrating the anatomical position of the retropharyngeal space.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis from arachidonic acid via the cyclo-oxygenase 1 and 2 pathways.Reference Nalamachu and Wortmann8 Indomethacin, an NSAID, inhibits predominantly cyclo-oxygenase 1 pathways, causing impaired platelet aggregation and a propensity for bleeding.Reference Warner, Giuliano, Vojnovic, Bukasa, Mitchell and Vane9 The literature describes retropharyngeal haematomas associated with warfarin, clopidogrel and aspirin, especially in the context of trauma.Reference Lin and Sinclair5,Reference Betten and Jaquint10 However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of an atraumatic retropharyngeal haematoma associated with indomethacin.

Case report

A 72-year-old female presented to a local hospital emergency department with odynophagia and anterior neck bruising. She was well until 5 days prior to her admission, when she had experienced sudden throat pain after coughing to clear her throat. She denied any trauma. She awoke the next day with shoulder and neck pain, and progressive dysphagia, feeling a diffuse burning neck pain when swallowing. Despite improvements to swallowing, 3 days after the sudden pain she presented to the emergency department after noticing increasing bruising across her anterior neck skin. Subjectively, her voice was deeper than normal, but there was no vocal hoarseness. She denied any airway issues, stridor or fevers.

On examination, there was significant ecchymosis of her anterior neck and upper chest, which progressed in the following days, but no palpable collections or masses (Figure 2a and 2b). There was visible ecchymosis of the posterior pharyngeal wall on direct visualisation of the oropharynx. However, she had no stridor or airway compromise, and demonstrated no restriction in neck movements. There was no palpable cervical lymphadenopathy. She had a normal pulse rate and blood pressure, and was afebrile. Flexible nasendoscopy demonstrated a bruised oedematous posterior pharynx, but no masses or other abnormalities were visible and her vocal folds mobilised normally (Figure 3).

Fig. 2. Clinical photography of the significant ecchymosis visible on the patient's anterior neck and chest wall, on: (a) the day of admission and (b) 3 days following admission.

Fig. 3. Flexible nasendoscopy image, demonstrating the posterior pharyngeal bruising.

She had suffered from chronic back pain for over 20 years and was taking indomethacin intermittently to manage her pain. Indomethacin had caused significant bruising to her limbs previously; consequently, she was reluctant to take it. For the past few months, her back pain had been more severe and she was using daily indomethacin prior to the onset of her neck bruising and odynophagia. She had no significant medical family history, had never smoked and drank 5 units of alcohol per week.

On admission, her blood tests demonstrated low haemoglobin (108 g/l) and very mildly raised fibrinogen (5.2 g/l), but her platelet count (212 × 109 per litre), international normalised ratio (1.0) and activated partial thromboplastin time ratio (0.88) were normal. Her white cell count (4.2 × 109 cells per litre) and neutrophil count were normal (2.2 × 109 cells per litre), but with a raised C-reactive protein level of 67 mg/l. Liver function test results and renal profile were unremarkable. She had a very mildly raised parathyroid hormone (PTH) level of 7.2 pmol/l (normal laboratory range of 1.8–6.8 pmol/l), but her thyroid function test results, and calcium and calcitonin levels, were all normal. The local emergency department had undertaken computed tomography (CT) of the neck and chest prior to transfer to the tertiary centre; this had revealed a 4 × 3 × 7 cm retropharyngeal haematoma (Figure 4). There were no vertebral fractures or signs of trauma.

Fig. 4. Computed tomography imaging requested in the emergency department, demonstrating the retropharyngeal haematoma.

She was admitted for observation and intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics (co-amoxiclav). Her indomethacin was stopped on admission, and haematologists were consulted. She tolerated a normal diet with mild odynophagia, and her observations remained normal. She was discharged with advice after 36 hours of observation, and given a 2-week course of oral co-amoxiclav antibiotics.

Upon review in clinic two weeks later, the patient reported that her dysphagia had settled over a week, and the neck and chest bruising had resolved after one to two weeks. She never experienced airway issues. She underwent out-patient serial blood investigations because of her raised parathyroid hormone level; these test results demonstrated that her calcium remained normal throughout, and the mildly raised PTH returned to normal. Of note, the serum and urine calcium concentration was normal (0.24 mmol/l). The local endocrine surgical and medical teams concluded that there was no evidence of a parathyroid adenoma, and the patient was discharged from out-patient care.

Discussion

The Capp's triad, described in 1934, refers to the commonly observed clinical and radiological findings in patients with retropharyngeal haematomas: subcutaneous bruising over the anterior neck and chest, anterior displacement of the trachea, and tracheal or oesophageal compression resulting in airway or swallowing problems.Reference Capps11 Although Capps initially described ‘mediastinal and subcutaneous haemorrhage’, his descriptions mirror today's terminology of ‘retropharyngeal haematomas’. Capps proposed spontaneous bleeding from one of multiple asymptomatic parathyroid adenomas as the cause,Reference Capps11 also described by Hellier and McCombe in 1997 in a patient with a mildly raised serum calcium level.Reference Hellier and McCombe12 Whilst our case demonstrated very mildly elevated PTH levels initially, the calcium levels remained normal and there was no biochemical evidence of parathyroid adenoma. Thus, the authors suggest that the mildly raised PTH may have arisen because the blood temporarily irritated one or more of the parathyroid glands, later self-resolving.

Anatomically, Penning et al. suggested that many cases of retropharyngeal haemorrhage may be secondary to bleeding from vessels overlying the anterior longitudinal ligament.Reference Penning13 Other authors proposed the thyrocervical trunk or its branch, the inferior thyroid artery, as a rarer source.Reference Van Valde, Sars, Olsman and Van de Hoeven14,Reference Calofero, Miller and Greenberg15 The authors propose that the combination of indomethacin affecting platelet aggregation, alongside the patient coughing (at the time of her symptom onset), may have led to this retropharyngeal haematoma; the coughing mechanism could have caused shearing forces as a result of attachments of the nearby fascial layers.

Consensus for likely bleeding sources has not been achieved, but Pfeiffer and Ridder described utilising a transcervical approach to: achieve endotracheal intubation, identify the bleeding defect, and enable insertion of a haemostatic agent and drain to surgically manage a retropharyngeal haematoma.Reference Pfeiffer and Ridder7 Other authors have performed CT angiograms to assess the bleeding location and evaluate its suitability for surgical intervention or embolisation.Reference Pfeiffer and Ridder7,Reference Betten and Jaquint10,Reference Van Valde, Sars, Olsman and Van de Hoeven14

Fortunately, surgical evacuation or transoral aspiration is rarely necessary, and would likely only be undertaken in cases of rapidly expanding or non-resolving haematomas.Reference Lin and Sinclair5 In patients using oral anti-coagulants and anti-platelet agents, reversal agents such as vitamin K and fresh frozen plasma should be considered, amongst other newer reversal therapies, to minimise bleeding.Reference Betten and Jaquint10,Reference Bloom, Haegen and Keefe16 However, reversal agents were not employed in this case, as indomethacin was the only potentially contributory medication and the patient was stable for 5 days prior to admission.

The literature describes varied management strategies for retropharyngeal haematoma with and without airway compromise. In this case, there was no evidence of airway compromise; in such instances, the majority of authors advocate conservative management, in the form of observation and antibiotic coverage, as was followed.Reference Duvillard, Ballester and Romanet3,Reference Lin and Sinclair5 Although steroids and antibiotics are frequently used, their benefit is unclear.Reference Bloom, Haegen and Keefe16 With rarer impending airway obstruction, some have advocated primary tracheostomy to avoid the potential, but unreported, risk of disrupting the retropharyngeal haematoma through endotracheal intubation.Reference Senthuran, Lim and Gunning4,Reference Van Valde, Sars, Olsman and Van de Hoeven14

Ongoing management can include serial CT imaging. However, the authors felt the clinical stability and resolution of this case with supportive measures did not warrant repeat imaging, and its associated radiation exposure.Reference Lin and Sinclair5 In conjunction with the literature, the patient was admitted for observation as, although documented in post-trauma patients, authors have warned of delayed stridor and airway compromise.Reference Lazott, Ponzo, Puana, Artz, Ciceri and Culp17 Our case was rare in its atraumatic nature, and no literature exists regarding follow-up duration in such cases. Comparatively, Penning studied 30 patients hospitalised with cervical spine injuries, and found that most retropharyngeal haematomas self-resolved within two weeks of the injury.Reference Penning13 Another study described resolution of traumatic retropharyngeal haematoma within four weeks.Reference Mitchell and Heniford18 This may suggest an appropriate guidance follow-up period. In our atraumatic case, the patient reported near-complete symptom resolution within two weeks.

This is the first reported atraumatic retropharyngeal haematoma presumed to be secondary to indomethacin use. The most similar cases include a report by Simckes et al., who described a peri-renal haematoma and irreversible renal failure following ketorolac use for pain management in sickle cell disease.Reference Simckes, Chen, Osorio, Garola and Woods19 Additionally, Buckley et al. used electron microscopy in rat models to demonstrate reduced platelet aggregation and significantly prolonged bleeding times after just one dose of ketorolac.Reference Buckley, Davidson and Das20 Of interest, Armstrong et al. described a mediastinal haematoma in a patient taking ketoprofen, with vigorous stirring of a Christmas pudding described as contributory, due to the presumed shearing forces generated.Reference Armstrong, Kirkby-Bott and Johnson21 Ketorolac and ketoprofen are NSAIDs, similar to indomethacin; perhaps, alongside our case, these studies suggest NSAIDs as a potential risk factor for atraumatic haematomas in various anatomical locations.

• Indomethacin can cause bleeding and haematomas; this is the first report of atraumatic retropharyngeal haematoma associated with indomethacin use

• Most advocate conservative management of retropharyngeal haematomas, in the absence of airway obstruction concerns

• This case of atraumatic retropharyngeal haematoma settled within two weeks with just observation and prophylactic oral broad-spectrum antibiotics

• Some suggest serial cross-sectioning imaging for monitoring traumatic cases

• In this case, with symptomatic improvement and in the absence of concerning clinical features, repeat imaging was not considered necessary

• This report contributes to the limited literature suggesting non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use may be a risk factor for atraumatic haematoma

Using our experience alongside the literature, we would suggest conservative management with observation and close discussion with the haematology department, providing there are no concerns regarding airway compromise or a rapidly enlarging haematoma. With naturally resolving symptomatology, we found serial imaging was not necessary. However, calcium and parathyroid hormone levels should be measured on admission, and any abnormalities must be investigated to exclude spontaneous haemorrhage from a parathyroid adenoma, as has previously been described.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the patient for kindly consenting to the publication of her case and associated images.

Competing interests

None declared