Introduction

Mucormycosis is an infection caused by mucorales fungi, within the class zygomycetes. The most common pathogens are from the genera mucorales, rhizopus, mucor and absidia.Reference Ribes, Vanover-Sams and Baker1

Clinically, there are five forms of mucormycosis: rhinocerebral, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, cutaneous and disseminated.Reference Yohai, Bullock, Aziz and Markert2 Rhinocerebral mucormycosis is the most common type, and classically occurs in immunocompromised patients with diabetic ketoacidosis, neutropenia, uraemia, burns, chronic corticosteroid therapy or severe malnutrition.Reference Mohindra, Gupta, Bakshi and Gupta3–Reference Yeung, Cheng, Lie and Yuen5

Inoculation occurs by inhalation; spores enter the nose and then spread to the paranasal sinuses and subsequently to the hard palate, orbit, meninges and brain by direct extension.Reference Yohai, Bullock, Aziz and Markert2, Reference Luna, Ponssa, Rodriguez, Luna and Juarez6

The diagnosis is made from clinical, microbiological and histopathological findings. The clinical manifestations of rhinocerebral mucormycosis are fever, headache, lethargy, decreased vision, ophthalmoplegia, and nasal or palatal black eschar. Death may follow in a few days, especially in undiagnosed and severely immunocompromised patients. Pathologically, the disease involves thrombosis, vascular invasion, ischaemia and infarction.

There are few published series of rhinocerebral mucormycosis containing sufficient patient numbers to enable analysis of predictors of survival.Reference Yohai, Bullock, Aziz and Markert2, Reference Blitzer, Lawson, Meyers and Biller7, Reference Peterson, Wang, Canalis and Abemayor8 The purpose of this report is to present our experience with 14 patients with rhinocerebral mucormycosis.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the outcomes of 14 patients referred to the University of Erciyes Otorhinolaryngology Department between January 2000 and December 2009. We reviewed the following data for all patients: age, gender, predisposing illness(es), clinical symptoms and findings, imaging results, pathological diagnosis, microbiological results, laboratory findings, surgical procedures, and treatment outcomes. Computed tomography (CT) scans had been obtained for all patients, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans for four.

Biopsies were taken from all patients suspected of mucormycosis, for histopathological analysis and culture. Microbiological studies were performed on tissue biopsies inoculated onto Sabouraud's agar and incubated at 30°C. A sample was also examined under light microscopy in 20 per cent potassium hydroxide. The histopathological diagnosis was primarily determined from tissue morphology, using haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), periodic acid Schiff, and Gomori's methenamine silver staining. In all cases, histopathological examination identified invasive, broad, thick-walled, nonseptate hyphae branching at right angles.

All patients received initial empirical treatment with either amphotericin B or liposomal amphotericin B. After histopathological diagnosis, surgical treatment was undertaken immediately.

Results

Our patients comprised seven males and seven females, with a mean age of 52.4 years (range nine to 75 years).

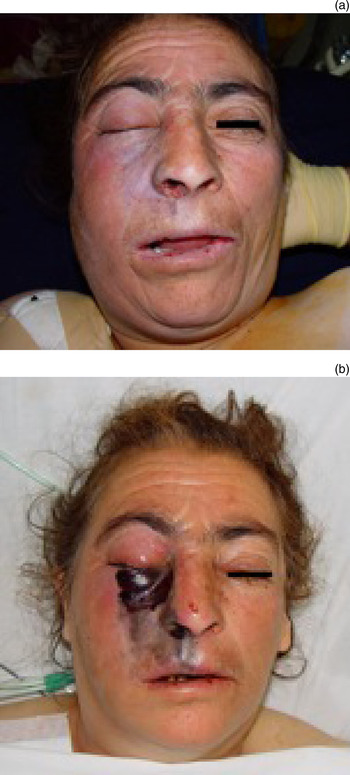

Nine patients (64 per cent) had diabetes mellitus type II; of these, two (14 per cent) had chronic renal failure. One patient (7 per cent) had diabetic ketoacidosis (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 Clinical photographs of patient 14, showing (a) right-sided facial palsy, ptosis and skin necrosis on admission, and (b) appearance after 12 hours, before surgical intervention. The fungal infection can be seen to have progressed rapidly. Published with permission.

Six patients (42 per cent) had a haematological malignancy (one also had diabetes mellitus). Of these six patients, three had acute myeloid leukaemia, one had acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and two had chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. All patients with haematological malignancy had been treated with long-term immunosuppressive therapy. One patient with haematological malignancy was in septic shock at initial evaluation.

The common presenting symptoms in all patients were fever, facial oedema, facial pain and nasal obstruction. On physical examination, common findings were nasal discharge, grey or black nasal eschar, periorbital cellulitis, palatal eschar, proptosis, ptosis, and altered consciousness.

On initial examination, nine (64 per cent) patients had cutaneous and/or palatal necrosis (three had both palatal and skin necrosis); of these, five (35 per cent) also had ophthalmoplegia and blindness. Four (29 per cent) patients also had facial palsy (Figure 2).

Fig. 2 Clinical photograph of patient 5 on admission, showing (a) left-sided facial palsy and ptosis, and (b) left-sided ophthalmoplegia. Published with permission.

On nasal endoscopy, grey or black mucosa was observed on the middle turbinate in eight patients and on the inferior turbinate in two patients. Four patients had large necrotic areas in the nasal cavity.

In the diabetic patients, the mean fasting blood glucose concentration was 281 mg/dl. The mean fasting blood glucose was 356 mg/dl in patients who died and 147 mg/dl in those who survived. The mean white blood cell count was 12 600/dl in the diabetes mellitus group. Five of the six patients with haematological malignancy had severe neutropenia (<1000/dl), while one had lymphocytosis (61 000/dl).

Biopsies were taken from all patients (13 nasal and three palatal or skin). On direct light microscopy with potassium hydroxide (20 per cent), fungal micro-organisms were seen for nine of the 14 (64 per cent) patients. On tissue culture, seven (50 per cent) samples grew rhizopus (subgroup unidentified), while three samples grew mixed fungal micro-organisms (rhizopus and candida). All patients had a histopathological diagnosis of mucormycosis (Figure 3).

Fig. 3 Photomicrograph showing invasive, nonseptate, branching hyphae (arrows). Note angioinvasion and prominent perivascular inflammatory infiltration. (Periodic acid Schiff; ×400)

Computed tomography, performed at initial evaluation, showed nonspecific sinusitis findings unilaterally in 10 (71 per cent) patients and bilaterally in four (29 per cent). Seven (50 per cent) patients had frontal and/or sphenoid sinus involvement. Two had visible bone defects (Figure 4).

Fig. 4 (a) Coronal computed tomography (CT) scan of patient 1, showing opacification of the left maxillary sinus and ethmoid cells, thickening of the orbital muscles, and decalcification of the medial and inferior walls of the left orbit. (b) Axial CT scan showing proptosis, thickening of the orbital muscles, and opacification of the left ethmoid cells and sphenoid sinus.

Patients received a combination of medical and surgical treatment. Medical management consisted of amphotericin B or liposomal amphotericin B: 11 patients (79 per cent) received amphotericin B (0.75–1.5 mg/kg) and five (35 per cent) liposomal amphotericin B (3–5 mg/kg) (two of these had previously received amphotericin B treatment). One patient was treated with local amphotericin B in addition to systemic amphotericin B.

Severe adverse effects developed in two patients (14 per cent) during medical therapy: severe hypokalaemia in one and an allergic reaction in the other. In both cases, amphotericin B was ceased and liposomal amphotericin B commenced. Six of the 10 (60 per cent) patients receiving amphotericin B and three of the five (60 per cent) receiving liposomal amphotericin B died.

Endoscopic sinus surgery was performed in five (36 per cent) patients with disease limited to the sinonasal cavity. More extensive resection was performed in nine (64 per cent) patients with advanced disease (presenting with findings such as skin and palatal necrosis, and/or ophthalmoplegia with blindness). Eight (57 per cent) patients underwent partial (n = 3) or total (n = 5) maxillectomy, of whom five also underwent orbital exenteration (36 per cent) (Figure 5). Two patients had widespread pterygopalatine fossa involvement and unclear surgical borders (Table I). One patient who was disorientated on presentation was suspected of intracranial involvement, but early imaging was normal.

Fig. 5 Coronal computed tomography scan of patient 5 following total maxillectomy with orbital exenteration.

Table I Patients’ clinical findings, treatment and outcome

*Evidence of bone erosion.†Insufficient resection. Pt no = patient number; y = years; CT = computed tomography; FU = follow-up; M = male; F = female; HM = haematological malignancy; DM = diabetes mellitus; CRF = chronic renal failure; DKA = diabetic ketoacidosis; L = left; R = right; mid = middle; inf = inferior; max = maxillary; ethm = ethmoid; front = frontal; sphen = sphenoid; AmB = amphotericin B; L-AmB = liposomal amphotericin B; wk = weeks; mth = months; d = days

Of the five (36 per cent) surviving patients, none had skin, palatal or orbital involvement on initial evaluation, nor any sign of frontal, sphenoid or bilateral paranasal sinus involvement on paranasal CT scanning.

The overall mortality rate was 64 per cent (nine of 14). The mean age of the deceased patients was 48.6 years, and that of the surviving patients 59.2 years. Intracranial involvement was the cause of death in five of the nine diabetic patients (55 per cent) and five of the six (83 per cent) patients with haematological malignancy (all five had neutropenia) (Figure 6). In patients who died, the mean time from presentation to death was 25 days (range 3–59 days).

Fig. 6 Axial, T1-weighted magnetic resonance image of patient 5 obtained after 10 days of hospitalisation, showing multiple hyperintense foci within the brain tissue.

In surviving patients, the follow-up period ranged from six to 15 months.

Discussion

Mucormycosis usually develops in severely immunocompromised patients, e.g. those with diabetes mellitus and diabetic ketoacidosis. The other predisposing factors are haematological malignancy, chronic renal failure, severe burns, iatrogenic immunosuppression and deferoxamine therapy.Reference Mohindra, Gupta, Bakshi and Gupta3–Reference Yeung, Cheng, Lie and Yuen5, Reference Sims and Zeichner9

The disease usually commences in the nose and spreads by direct extension and intravascular propagation to involve the paranasal sinuses, orbit, cribriform plate, meninges and brain. The clinician must entertain a high index of suspicion for the disorder when managing severely immunocompromised patients.

It is important to be aware of early signs and symptoms.

The initial signs of infection are usually nonspecific. Fever, facial oedema, impaired vision and proptosis are the most common complaints.Reference Gillespie, O'Malley and Francis10–Reference Turunc, Demiroglu, Aliskan, Colakoglu and Arslan12 Fever of unknown origin which has not responded to 48 hours of appropriate intravenous broad spectrum antibiotics must alert the physician, but the absence of fever does not exclude the diagnosis.Reference Kennedy, Adams, Neglia and Giebink13 Fever may indicate more fulminant disease.Reference Hargrove, Wesley, Klippenstein, Fleming and Haik11

Other common symptoms are nasal obstruction or discharge, headache, epistaxis, and periorbital and/or facial pain. Orbital symptoms include loss of function of the second, third, fourth and sixth cranial nerves, with resultant ptosis, proptosis, chemosis, orbital pain, mydriasis and loss of vision.Reference Yohai, Bullock, Aziz and Markert2, Reference Pillsbury and Fischer14–Reference Talmi, Goldschmied-Reouven, Bakon, Barshack, Wolf and Horowitz16

The physical findings in patients with rhinocerebral mucormycosis are often as subtle as the presenting symptoms. Nasal endoscopy enables effective examination of high risk patients, to detect any changes in mucosal colour (i.e. white, grey or black) and/or texture (i.e. granulation or ulceration).Reference Gillespie, O'Malley and Francis10 Decreased mucosal bleeding or sensation should also alert the physician.Reference Bodenstein, McIntosh, Vlantis and Urquhart15, Reference Gillespie and O'Malley17 One study observed necrotic nasal mucosa lesions in 80 per cent of patients during the course of the disease.Reference Gravesen18

Head and neck examination should also be performed on all patients, in addition to endoscopic nasal evaluation.Reference Gillespie and O'Malley17 The cranial nerves, afferent pupillary reflex, visual acuity and facial sensation must be evaluated. Facial oedema associated with rhinocerebral mucormycosis may be confused with periorbital cellulitis; however, the periorbital oedema associated with rhinocerebral mucormycosis is soft, cool and non-tender, while the oedema of cellulitis is firm, warm and tender. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis produces a paralytic ptosis: the examiner can raise the eyelid easily, but the oedematous ptosis of cellulitis resists active lid opening.Reference Bodenstein, McIntosh, Vlantis and Urquhart15

The oral cavity and oropharynx should also be examined. Unilateral gangrene and perforation of the hard and soft palates may occur due to involvement of the palatine arteries.Reference Gillespie and O'Malley17, Reference Alleyne, Vishteh, Spetzler and Detwiler19

The diagnosis of rhinocerebral mucormycosis is best made by histological evaluation of infected tissue. Infection usually begins along the middle or inferior turbinate.Reference Ferguson20 Biopsies can be taken from commonly involved areas such as the middle turbinate even in the absence of marked mucosal abnormality.Reference Gillespie and O'Malley17 Most of the patients presented in this study had evidence of necrosis on the middle or inferior turbinate.

Histologically, the fungi are characterised by broad, thick-walled, nonseptate hyphae that branch at right angles. There is a distinct proclivity for vessel wall invasion, which causes thrombosis with resultant ischaemia and infarction.Reference Alleyne, Vishteh, Spetzler and Detwiler19 In contrast to most fungi, the aetiological agents of mucormycosis are readily seen on H&E-stained tissue sections.Reference Ferguson20 Due to the possibility of contamination, the diagnosis should be verified histologically rather than by positive microbial cultures.Reference Peterson, Wang, Canalis and Abemayor8, Reference Jung, Kim, Park, Song, Cho and Lee21 Waiting for cultures may also delay the initiation of treatment. If a clinical picture of mucormycosis exists, positive direct smears may be sufficient to justify treatment.Reference Talmi, Goldschmied-Reouven, Bakon, Barshack, Wolf and Horowitz16

Computed tomography and MRI scans may be suggestive of invasive mucormycosis, but they are often nondiagnostic. The most common CT findings include mild mucosal sinus thickening and extraocular muscle thickening. Lateral displacement of the medial rectus muscle is frequently seen. Later findings may include frank abscess and sinus opacification (often without air–fluid levels), together with extension into the orbit, orbital apex or brain. If angio-invasion is present, bone erosion may be absent even in the presence of progressive disease. Magnetic resonance imaging evidence of sinus involvement may range from hyperintensity on T2-weighted scans to marked hypointensity on all sequences, often with obliteration of normal fat planes. The T2-weighted modality is typically more useful than T1-weighted scans for the evaluation of extension into the orbital apex, cavernous sinus or brain. Computed tomography is considered best for the evaluation of bony involvement, while MRI is best for evaluating the cranial nerves and cavernous sinuses.Reference Spellberg, Edwards and Ibrahim22–Reference Terk, Underwood, Zee and Colletti24 Overall, CT and MRI may be most useful in assisting surgical planning for, rather than diagnosis of, rhinocerebral mucormycosis. In this study, CT scans showed nonspecific sinusitis findings unilaterally in 10 patients and bilaterally in four. Two patients had CT evidence of bone necrosis on admission. Of the nine patients (64 per cent) who had involvement of the frontal, sphenoid or bilateral paranasal sinuses, all died of their disease.

The mainstays of rhinocerebral mucormycosis therapy are reversal of the source of immunocompromise, high dose systemic amphotericin B and surgical debridement of nonviable tissue.Reference Mohindra, Gupta, Bakshi and Gupta3, Reference Ferguson20, Reference Weir, Golding-Wood, Kerr, MacKay and Bull25, Reference Avet, Kline and Sillers26 Depending on the predisposing disease, mortality rates range from 33 to 85 per cent.Reference Blitzer, Lawson, Meyers and Biller7, Reference Hargrove, Wesley, Klippenstein, Fleming and Haik11, Reference Jung, Kim, Park, Song, Cho and Lee21, Reference Roden, Zaoutis, Buchanan, Knudsen, Sarkisova and Schaufele27 Mortality increases to 100 per cent in paediatric haematological patients with rhinocerebral mucormycosis.Reference Zaoutis, Roilides, Chiou, Buchanan, Knudsen and Sarkisova28

Correcting underlying factors is of the utmost importance, for example, normalising hyperglycaemia and ketoacidosis in the case of diabetics, and controlling neutropenia in patients with haematological malignancy.Reference Yohai, Bullock, Aziz and Markert2, Reference Peterson, Wang, Canalis and Abemayor8, Reference Hargrove, Wesley, Klippenstein, Fleming and Haik11, Reference Pagano, Ricci, Tonso, Nosari, Cudillo and Montillo29

However, the possibility of correction is hardly applicable to oncological patients.Reference Mohindra, Gupta, Bakshi and Gupta3, Reference Talmi, Goldschmied-Reouven, Bakon, Barshack, Wolf and Horowitz16, Reference Eucker, Sezer, Graf and Possinger30–Reference Kontoyiannis and Lewis32 Neutrophils are the primary defence against fungal infections such as mucormycosis, and neutropenia can increase the risk of infection.Reference Rosenberg and Lepley33–Reference Hejny, Kerrison, Newman and Stone35 Absolute neutrophil counts below 500 cells/ml are strongly correlated with the development of invasive fungal disease.Reference Lueg, Ballagh and Forte36 The use of granulocyte colony stimulating factor may be useful in neutropenic patients.Reference Sahin, Paydas, Cosar, Bicakci and Hazar37 Surgery does not prolong survival in neutropenic patients who do not recover their white blood cell count.Reference Gillespie, O'Malley and Francis10

The predisposition of diabetes mellitus patients to rhinocerebral mucormycosis is probably related to hyperglycaemia and acidosis. The acidotic environment is believed to promote both phagocytic dysfunction and a decrease in the iron-binding capacity of the blood. In previous reports, up to 60–80 per cent of patients with mucormycosis had diabetes mellitus, and one-third to one-half of these diabetic patients were in diabetic ketoacidosis at the time of infection.Reference Jung, Kim, Park, Song, Cho and Lee21, Reference Bonifaz, Macias, Paredes-Farrera, Arias, Ponce and Araiza38 Recent studies have found a decreasing incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis, because the characteristic signs and symptoms of the disease are now well recognised by physicians. Patients with underlying diseases that take longer to correct are known to have a lower survival rate for mucormycosis.Reference Hargrove, Wesley, Klippenstein, Fleming and Haik11 Diabetics usually have a better prognosis than immunocompromised or leukaemic patients.Reference Blitzer, Lawson, Meyers and Biller7, Reference Hargrove, Wesley, Klippenstein, Fleming and Haik11, Reference Scheckenbach, Cornely, Hoffmann, Engers, Bier and Chaker39

In the present study, five of the six (83 per cent) patients with haematological malignancy had neutropenia, and all five died. The incidence of diabetes mellitus in our patients (64 per cent) was similar to previous reports; however, the incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis was lower (11 per cent).Reference Jung, Kim, Park, Song, Cho and Lee21, Reference Bonifaz, Macias, Paredes-Farrera, Arias, Ponce and Araiza38 Five of our nine diabetic patients (55 per cent) died. These high mortality rates may be related to advanced disease and uncontrolled underlying conditions.

Upon diagnosis of rhinocerebral mucormycosis, high-dose amphotericin B therapy should be instituted immediately. Because of the potential for nephrotoxicity, patients' renal function must be closely monitored.

A number of other methods show promise in the treatment of rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Local application of amphotericin B allows increased concentration of the drug at the source of active infection. Liposomal preparations of amphotericin B may allow the use of this antifungal agent while reducing systemic toxicity.Reference Ferguson20, Reference Avet, Kline and Sillers26 In general, liposomal amphotericin B is reserved for clinically proven fungal infection in an immunocompromised patient with an elevated serum creatinine concentration (greater than 2.5 mg/dl), or progression of fungal disease while receiving the maximal dosage of standard amphotericin B (1.25 mg/kg/day).Reference Gillespie and O'Malley17 Liposomal amphotericin B is safer but more expensive than conventional amphotericin B.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has also proven useful.Reference Kontoyiannis and Lewis32, Reference John, Chamilos and Kontoyiannis40, Reference Simmons, Zeitler, Fenton, Abzug, Fiallo-Scharer and Klingensmith41

Posaconazole may be useful in individuals at risk due to neutropenia, steroid therapy or treatment with immunosuppressive agents.Reference Greenberg, Scott, Vaughn and Ribes31 In the present study, two (14 per cent) patients developed severe adverse effects during amphotericin B therapy, requiring its cessation.

Patients with mucormycosis limited to the nasal cavity have a higher incidence of survival. If diagnosed at this stage, the disease is more amenable to complete endoscopic surgical resection.Reference Gillespie, O'Malley and Francis10, Reference Ferguson20, Reference Avet, Kline and Sillers26 All tissue that is grossly involved must be removed, since antifungal therapy alone will not suffice. Debridement must be continued until a margin of healthy tissue is encountered, and should be performed at frequent intervals.

More extensive surgical treatment may include sinus surgery, wide resection of necrotic soft tissue and bone, and exenteration of the orbit if needed.Reference Scheckenbach, Cornely, Hoffmann, Engers, Bier and Chaker39 The orbit is the portal of entry for infection of the central nervous system. The most difficult decision in the management of orbital mucormycosis is whether or not to undertake orbital exenteration. In general, the indications for orbital exenteration are ophthalmoplegia, proptosis, cranial nerve involvement, cranial involvement and ocular involvement (e.g. central retinal artery occlusion).Reference Hargrove, Wesley, Klippenstein, Fleming and Haik11, Reference Talmi, Goldschmied-Reouven, Bakon, Barshack, Wolf and Horowitz16, Reference Alleyne, Vishteh, Spetzler and Detwiler19, Reference Weir, Golding-Wood, Kerr, MacKay and Bull25 However, several reports have documented patient survival without exenteration, in the presence of clinical orbital involvement.Reference Hejny, Kerrison, Newman and Stone35, Reference Tarani, Costantino, Notheis, Wintergerst, Venditti and Di Biasi42, Reference Kohn and Hepler43

Patients with frontal sinus involvement are less likely to survive than those without such involvement. Palatal and facial necrosis are also negative factors for survival.Reference Hargrove, Wesley, Klippenstein, Fleming and Haik11 Palatal involvement occurs in approximately 18 per cent of mucormycosis cases, and the mortality rate is approximately 80 per cent.Reference Eucker, Sezer, Graf and Possinger30, Reference Bonifaz, Macias, Paredes-Farrera, Arias, Ponce and Araiza38, Reference Fingeroth, Roth, Talcott and Rinaldi44

Aggressive surgical debridement to remove disease outside the sinonasal cavity rarely attains negative margins or improves long-term survival.Reference Gillespie, O'Malley and Francis10, Reference Kennedy, Adams, Neglia and Giebink13 Patients with intracranial spread are less likely to respond to radical surgery, and their prognosis is extremely poor.Reference Turunc, Demiroglu, Aliskan, Colakoglu and Arslan12, Reference Anaissie and Shikhani45 When radical surgery is considered, such patients should be appropriately counselled.Reference Gillespie and O'Malley17

In the present study, five patients had limited disease involving only the nasal cavity; all five recovered. However, nine (64 per cent) of our patients had skin and/or palatal necrosis, and five of these nine had ophthalmoplegia. Although radical surgical procedures were performed (e.g. maxillectomy and orbital exenteration), all nine patients died.

In patients with rhinocerebral mucormycosis, factors associated with poor prognosis include delayed initiation of treatment, ophthalmoplegia, blindness, bilateral disease, skin necrosis, palatal involvement, symptomatic intracranial involvement and renal disease.Reference Yohai, Bullock, Aziz and Markert2, Reference Talmi, Goldschmied-Reouven, Bakon, Barshack, Wolf and Horowitz16 Our results show that orbital involvement, skin necrosis, palatal involvement, radiologically bilateral involvement, and sphenoid or frontal sinus involvement are indicators of poor prognosis. In cases of rhinocerebral mucormycosis, control of underlying diseases is at least as important as medical and surgical therapy.

Conclusion

Mucormycosis is a serious disease and may be fatal if not treated in time. A high index of clinical suspicion, early diagnosis and immediate correction of underlying medical disorders are important factors for a favourable prognosis. However, the prognosis is poor in patients with rhinocerebral mucormycosis that has spread outside the sinonasal cavity despite aggressive medical and surgical therapy. Involvement of the skin, palate and orbit are poor prognostic factors. The survival rate is better in patients with diabetes mellitus than in those with haematological malignancy.