Introduction

Anomalies of the third and fourth branchial apparatus, although rare, usually present as sinuses or incomplete fistulae of the pyriform sinus.Reference Madana, Yolmo, Gopalakrishnan and Saxena1 The fistulous tract originates from the pyriform sinus, penetrates the cricothyroid muscle and terminates in the lateral lobes of the thyroid gland.Reference Seki and Himi2 This congenital anomaly manifests itself as recurrent neck abscesses or acute suppurative thyroiditis. The condition is usually noted during the first decade of life, more frequently on the left than the right. Hence, a diagnosis of pyriform sinus fistula should be suspected in all paediatric cases of recurrent, left-sided neck abscesses or acute suppurative thyroiditis. Surgical removal of the entire fistulous tract together with hemithyroidectomy, during an inflammation-free period, is the definitive treatment.Reference Ahuja, Griffiths, Roebuck, Loftus, Lau and Yeung3

Herein, we present a retrospective review of 15 paediatric cases of pyriform sinus fistulae associated with a third branchial pouch anomaly and generally presenting with recurrent, left-sided, suppurative thyroiditis, treated between 2000 and 2008. Fistulectomy with left hemithyroidectomy was performed on all patients. This article summarises the anatomy of these lesions and reviews their clinical presentation and treatment.

Methods

We undertook a retrospective review of 15 paediatric cases of third branchial arch anomaly with associated pyriform sinus fistulae treated in the otolaryngology department of Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Pondicherry, India, between 2000 and 2008. The diagnosis was made on the basis of pre-operative radiological demonstration of a fistulous tract (using barium swallow and computed tomography (CT) fistulography), intra-operative findings and histopathological analysis. Fistulectomy with left hemithyroidectomy was performed in all cases.

Results

The main results are summarised in Table I.

Table I Patient summary

Pt no = patient number; y = years; intra-op PSF = intra-operative pyriform sinus fistula; F = female; M = male; L = left; += positive for pyriform sinus fistula; – = negative for pyriform sinus fistula

The patients comprised six boys and nine girls ranging in age from three to 15 years (median age, 10 years; mean age, nine years). Eleven cases (73.4 per cent) presented with recurrent thyroid abscesses (see Figure 1, case two), while two children (13.3 per cent) presented with their first episode of thyroid abscess (see Figure 2, case 14). The remaining two patients (13.3 per cent) presented with a fistulous opening in the left lower neck (see Figure 3, cases three and 10).

Fig. 1 Clinical photograph of a six-year-old girl (case two) with recurrent thyroid abscess.

Fig. 2 Clinical photograph of a three-year-old girl (case 14) presenting with her first episode of thyroid abscess.

Fig. 3 (a) Clinical photograph of a 15-year-old girl (case three) with a fistula in the left side of the neck. (b) Clinical photograph of a 14-year-old boy (case 10) with a fistula in the left side of the anterior neck.

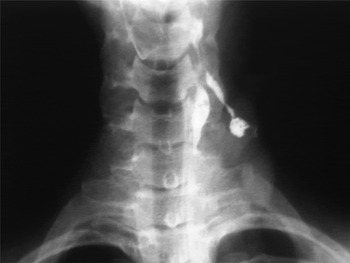

In 12 cases (80 per cent), the fistula was detected by pre-operative radiological evaluation in the form of barium swallow study (Figure 4) and/or CT fistulography (Figure 5). Computed tomography was used in case 10 to reveal the presence of air in the posterior aspect of the left thyroid lobe (Figure 6), and in case 14 to reveal a hypodense lesion involving the whole of the left thyroid lobe, suggestive of an abscess (Figure 7).

Fig. 4 Barium swallow X-ray image showing a fistulous communication between the left pyriform sinus at its base and the soft tissue of the ipsilateral neck.

Fig. 5 Axial computed tomography fistulography scan showing a fistulous tract extending from the neck skin to the left thyroid lobe and communicating with the base of the left pyriform sinus, resulting in visible dye in the hypopharynx.

Fig. 6 Axial computed tomography scan for case 10, showing the presence of air (arrow) in the posterior aspect of the left lobe of the thyroid gland.

Fig. 7 Axial computed tomography scan for case 14, showing a hypodense lesion involving the whole of the left thyroid lobe, suggestive of an abscess. R = right

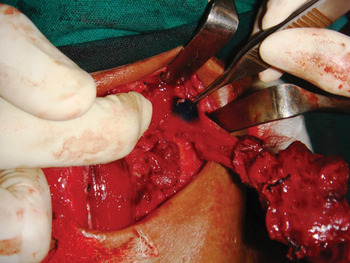

Intra-operative identification of the fistulous tract (Figure 8), followed by its histopathological confirmation, was possible in all 15 cases. Other pathological findings included an adenomatous goitre in case three.

Fig. 8 Surgical photograph showing intra-operative identification of the fistulous tract by the detection of methylene blue dye, following endoscopic guided injection into the internal opening at the ipsilateral pyriform sinus.

In all cases, the post-operative period was uneventful with no complications. There was no recurrence over three to five years of regular follow up.

Discussion

Background

Von Baer described the existence of the cervical branchial apparatus in 1827.Reference Myer, Paparella and Shumrick4 The term branchial fistula was first used by Heusinger.Reference Heusinger5 In 1912, Wenglowski postulated the branchiogenic origin of lateral cervical cysts, based on his work with the human embryo and with cadaver dissection.Reference Wenglowski6

The human branchial apparatus consists of five pairs of mesodermal arches separated by four pairs of ectodermal and endodermal pouches or clefts. Branchial fistulae originate from the remnants of the pouches and clefts following rupture of the interposing branchial plate. More than 90 per cent of branchial anomalies arise from the second arch, and 8 per cent from the first arch. Anomalies of the third and fourth branchial apparatus, although rare, usually present as sinuses or incomplete fistulae of the pyriform sinus, or as recurrent suppurative thyroiditis.Reference Madana, Yolmo, Gopalakrishnan and Saxena1 Kubota et al. were the first to observe that pyriform sinus fistulae may cause suppurative thyroiditis in infants and children.Reference Kubota, Suita, Kamimura and Zaizen7

Embryology

The embryological basis of pyriform sinus fistulae was originally theorised to be the remnant of the branchial apparatus, particularly the third or the fourth pharyngeal pouch, reported by Sandborn and Shafer in 1972.Reference Sandborn and Shafer8 In 1973, Tucker and Skolnick demonstrated the existence of a fistulous tract, using a barium swallow study.Reference Tucker and Skolnick9 Takai et al. reported seven cases of acute suppurative thyroiditis caused by pyriform sinus fistulae, and advised the proper examination of the hypopharynx in all such cases.Reference Takai, Miyauchi, Matsuzuka, Kuma and Kosaki10 On the basis of the histological appearance of C cells, Miyauchi et al. proposed the derivation of pyriform sinus fistula from the fifth pouch (the ultimobranchial body).Reference Miyauchi, Matsuzuka, Kuma and Katayama11 During embryological development, the third and fourth branchial pouches are connected to the pharynx by the pharyngobranchial duct, which degenerates by the seventh week. Persistence of this duct results in formation of a sinus or fistulous tract that communicates with the pyriform sinus. The origin of the tract from the third pharyngeal pouch is based on its anatomical course in the neck.Reference Madana, Yolmo, Gopalakrishnan and Saxena1, Reference Seki and Himi2

The course of third branchial arch fistulae presumably originates from the cephalic region of the pyriform sinus, anterior to the fold made by the internal laryngeal nerve.Reference Madana, Yolmo, Gopalakrishnan and Saxena1 The fistula then pierces the thyrohyoid membrane cranial to the superior laryngeal nerve and passes over the hypoglossal nerve. It courses behind the internal carotid artery and runs superficial to the superior laryngeal nerve, and then passes through the thyroid lobe, mostly on the left side, sometimes to terminate in the cervical neck along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the junction of its upper two-thirds and lower third.Reference Madana, Yolmo, Gopalakrishnan and Saxena1, Reference Mali and Prabhakaran12

Fourth branchial fistulae follow a ‘two-loop course’, originating from the caudal end of the pyriform fossa, posterior to the fold made by the internal laryngeal nerve, and coursing inferiorly along the tracheoesophageal groove, posterior to the thyroid gland, into the mediastinum, to loop around the aorta (if on the left side) or the subclavian artery (if on the right). The fistula then ascends cephalad to pass over the hypoglossal nerve before piercing the platysma to end on the cervical neck.Reference Madana, Yolmo, Gopalakrishnan and Saxena1, Reference Mali and Prabhakaran12, Reference Chaudhary, Gupta, Motwani and Kumar13

The theory of fifth pouch (ultimobranchial body) pyriform sinus fistula derivation is based on its predominance on the left side, which may be due to the asymmetrical development of the fourth branchial arch, which becomes part of the aortic arch on the left side and the right subclavian artery on the right. This may be explained by the lack of an ultimobranchial body in the right side of the neck. Although the origin of pyriform sinus fistulae from the fifth arch cannot be clearly indicated, ultimobranchial body derived C cells near the fistulous tract might play a role in the formation of pyriform sinus fistulae.Reference Seki and Himi2

Clinical course

Third arch anomalous pyriform sinus fistulae present as recurrent acute suppurative thyroiditis, retropharyngeal abscess or perithyroid abscess, with symptoms such as unilateral neck swelling, local erythema, pain, fever, dysphagia and respiratory distress.Reference Seki and Himi2 In our patients, recurrent acute suppurative thyroiditis was the most common mode of presentation (73.4 per cent), followed by a first episode of acute suppurative thyroiditis (13.3 per cent) and a fistulous opening at the neck (13.3 per cent). The thyroid gland is resistant to bacterial infection because of its rich blood supply, extensive lymphatics, high iodide content, and tough capsule separating it from surrounding sources of contamination. Hence, recurrent inflammation of the thyroid gland should suggest an underlying lower branchial abnormality with pyriform sinus fistula formation.Reference Seki and Himi2, Reference Ahuja, Griffiths, Roebuck, Loftus, Lau and Yeung3

Diagnosis

In children, the diagnosis requires a high index of clinical suspicion in the face of left-sided neck abscess.

A barium swallow study may be useful to identify the fistulous tract if performed approximately four to six weeks following an acute inflammatory phase; if performed earlier, the oedematous wall of the tract may not allow barium to pass.Reference Seki and Himi2

A CT scan may be performed after the barium swallow (in cases of suppurative thyroiditis); however, a direct contrast injection (in cases of neck fistula) through the cannulated external opening will be more useful in delineating the anatomical course of the entire tract than a plain CT scan. The presence of air near the lesser horn of the thyroid cartilage on CT scanning is considered pathognomonic, even during inflammation; however, this sign is inconstant.Reference Madana, Yolmo, Gopalakrishnan and Saxena1 An air pocket may also be present within the posterior part of the thyroid gland (see Figure 6, case 10). Computed tomography is also necessary to exclude other lateral cervical pathology and to guide the plane and direction of fistulectomy. Few authors have reported the usefulness of air CT, wherein air is used as a contrast agent (administered by having the patient drink carbonated water instead of barium).Reference Seki and Himi2 The use of modified Valsalva and trumpet manoeuvres during CT scanning and ultrasonography also enables air to be utilised as a contrast agent, tracing the course of the tract.Reference Madana, Yolmo, Gopalakrishnan and Saxena1

Endoscopy is useful for diagnosis, and should be performed under general anaesthesia. Since it is an invasive procedure, we do not routinely recommend it, unless barium swallow fails to identify a tract despite strong clinical suspicion of a pyriform sinus fistula in a child with suppurative thyroiditis.

We could not demonstrate a fistulous tract pre-operatively in three of our patients (cases nine, 13 and 15), who all presented with recurrent suppurative thyroiditis. All these patients underwent surgery based on a strong suspicion of a pyriform sinus fistula. Intra-operatively, we identified the course of the tract under microscopic guidance, especially the section that emerged from the larynx posterior to the cricothyroid joint; we also ligated fistula-like structures and removed the infectious mass along with the left lobe of the thyroid (with preservation of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve). Histopathological findings were compatible with pyriform sinus fistulae, with lumens lined by pseudostratified, ciliated epithelium and tract walls showing fibrous hypertrophy with moderate inflammatory infiltration. These patients had no recurrence of symptoms.

Treatment

In cases of suppurative thyroiditis, incision and drainage must be performed on an emergency basis; however, this makes the subsequent surgery more difficult. Pre-operative administration of appropriate antibiotics is useful to reduce inflammation.Reference Seki and Himi2 However, complete excision of the fistulous tract with a partial or hemithyroidectomy, during a quiescent period, is the treatment of choice.

If the fistulous tract is longer, a step-laddered incision may be used. Adequate exposure may be provided by the Woodman approach, or by retracting or excising a vertical strip of the posterior border of the thyroid ala. Some investigators believe that complete disconnection of the tract from the pyriform sinus at the level of the thyrohyoid membrane is sufficient.

Intra-operative cannulation, with or without injection of 1 per cent methylene blue dye into the pyriform sinus opening under endoscopic or laryngoscopic guidance, is effective in localising the course of the fistulous tract.Reference Madana, Yolmo, Gopalakrishnan and Saxena1, Reference James, Stewart, Warrick, Tzifa and Forte14 Incomplete excision carries a high risk of recurrence.

• Fifteen paediatric pyriform sinus fistula cases are presented

• Suppurative thyroiditis (especially recurrent and left-sided) should prompt suspicion of pyriform fossa fistula with third or fourth branchial pouch anomaly

• Barium swallow, computed tomography fistulography and intra-operative pyriform fossa dye injection are useful

• Surgical treatment should be considered

• Delayed recurrence is possible, usually after inadequate excision or excision during acute thyroiditis

Endoscopic obliteration of the fistula is possible with trichloroacetic acid, fibrin or an insulated electrocautery probe.Reference Seki and Himi2 Endoscopic treatment is a minimally invasive technique in which cauterisation is used to obliterate the internal opening of the pyriform sinus tract during a quiescent period. The advantages of this method over open surgery may include fewer complications and a reduced cost (as it can be performed as an out-patient procedure).

Open neck surgery and endoscopic cauterisation may have similar recurrence rates. To reduce complications, open surgery may be reserved for patients older than eight years of age, and endoscopic technique for those aged eight years or younger.Reference Nicoucar, Giger, Pope, Jaecklin and Dulguerov15

Treatment by chemocauterisation of the internal opening has also been reported, with encouraging results.Reference Garrel, Jouzdani, Gardiner, Makeieff, Mondain and Hagen16

Given the above results, endoscopic cauterisation is now preferred as first-line treatment of pyriform fossa sinus tracts, with open excision reserved for endoscopic failures.Reference Chen, Inglis, Ou, Perkins, Sie and Chiara17

Post-operative complications following open surgery include temporary vocal fold paralysis, salivary fistula and wound infection. These are more common in children younger than eight years.Reference Nicoucar, Giger, Pope, Jaecklin and Dulguerov18 Recurrence is possible many years after surgery, usually following inadequate excision or excision during an acute episode of suppurative thyroiditis. Hence, long-term follow up is necessary.Reference Madana, Yolmo, Gopalakrishnan and Saxena1 None of our cases suffered recurrence over a three to five year period of regular follow up.

Conclusion

The thyroid is remarkably resistant to infection. Hence, when an infection does occur, the presence of a pyriform fossa fistula with a third or fourth branchial pouch anomaly must be considered, particularly if the infection is recurrent and left-sided.

This study describes third branchial arch fistulae presenting as suppurative thyroiditis in children. Strong clinical suspicion was the key to diagnosis in these cases. Pre-operative barium swallow and/or CT fistulography were used to delineate the tract, together with intra-operative injection of dye into the ipsilateral pyriform sinus. Surgical removal is worthy of consideration in suspected pyriform sinus fistula cases, as it is in patients who have similar manifestations without pre-operative detection of the tract. Recurrence is possible many years after surgery, usually following inadequate excision or excision during an acute episode of suppurative thyroiditis.