Introduction

Hearing loss is a common presentation. It can be categorised as sudden or chronic based on the duration of symptom onset, or classified as conductive, sensorineural or mixed hearing loss based upon the portion of the auditory system affected. Sudden hearing loss where symptom onset is less than 72 hours, and chronic hearing loss where symptoms progress over a period of months to years, are both well-established presentations, with accepted clinical pathways for investigation and treatment.1,Reference Isaacson and Vora2

Hearing loss rarely presents as rapidly progressive occurring over weeks.Reference Kishimoto, Yamazaki, Naito, Shinohara, Fujiwara and Kikuchi3 Therefore, the literature is limited with regard to which pathologies the reviewing clinician should consider in rapidly progressive hearing loss cases, and how to approach such patients.

We report a case of bilateral rapidly progressive hearing loss occurring over 12 weeks, and present a review of the current literature.

Case report

A 59-year-old female presented to the otolaryngology out-patient clinic with a rapidly progressive, bilateral hearing loss over 3 months. She had also developed persistent vertigo and memory impairment over the same time period, and had been treated by an ophthalmologist for bilateral uveitis that was initially presumed be a herpetic infection.

She had previously been fit and well. Over the three-month period prior to her presentation to otolaryngology, she had been treated for herpes zoster infection of her chest wall with a subsequent persistent post-herpetic neuralgia. She had also experienced an isolated episode of sudden-onset, right-sided lower motor neurone facial nerve palsy that completely resolved following a 10-day course of high dose prednisolone (1 mg/kg).

At the otolaryngology review, the bilateral uveitis had persisted. The patient reported sequential, progressive hearing loss starting on the right side, followed by left-sided loss weeks later. The observed examination findings were within normal physiological parameters. Assessment of her ears, cranial nerves and peripheral neurological system also revealed grossly normal findings.

Pure tone audiometry demonstrated a bilateral sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) at close to 50 per cent from a baseline pure tone audiometry assessment performed three months prior when investigated in an otolaryngology casualty clinic for the previous right-sided, unilateral facial nerve palsy (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Patient's pure tone audiometry assessments. (a) Baseline pure tone audiometry performed at her initial presentation with unilateral lower motor neuron facial nerve palsy. (b) Pure tone audiometry conducted three months later, showing a significant deterioration in sensorineural hearing bilaterally. (c) Pure tone audiometry performed two months after treatment commencement for sarcoidosis, demonstrating improvements in hearing bilaterally. ![]() = air conduction – unmasked (right);

= air conduction – unmasked (right); ![]() = air conduction – unmasked (left);

= air conduction – unmasked (left); ![]() = air conduction – masked (left)

= air conduction – masked (left)

Given the rate of her hearing loss progression and the systemic nature of her symptoms, the patient was admitted for in-patient investigations and the initiation of intravenous corticosteroid treatment. Intravenous acyclovir was also administered in light of the suspicion of systemic herpes zoster infection.

A summary of the investigations carried out and the results are outlined in Table 1. A diagnosis of sarcoidosis was made based upon her symptoms, and on the findings of eventual endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration, which confirmed non-caseating granulomatous inflammation.

Table 1. Summary of patient's investigation results

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; CRP = C-reactive protein; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; Ig = immunoglobulin; ANA = anti-nuclear antibody; ANCA = antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; PR3 = proteinase 3; LIU = light intensity units; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; MRA = magnetic resonance angiogram; CT = computed tomography; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; EBUS-TBNA = endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration

The patient was subsequently started on a long-term course of oral prednisolone. A repeat pure tone audiometry conducted two months after commencing treatment confirmed near-complete resolution of her hearing loss (Figure 1c). Her vertiginous symptoms and memory impairment had also improved. She was discharged from otolaryngology follow up, and has continued under the care of her neurologist for the introduction of hydroxychloroquine and tapering of the oral steroid dosage.

Materials and methods

A review of the patient's notes was undertaken to compile the case report.

A literature review was carried out involving a PubMed search performed in June 2021, utilising the following search strategy (with Boolean operators): (‘rapidly progressive hearing loss’ OR ‘subacute hearing loss’). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) definition of rapidly progressive hearing loss was used.4 The NICE defines rapidly progressive hearing loss as a hearing loss occurring over 4–90 days (Figure 2).4

Fig. 2. Possible hearing loss presentations by the duration of symptom onset.4

Results

Twenty-three studies were reviewed to identify the underlying pathologies responsible for rapidly progressive hearing loss (Figure 3).Reference Kishimoto, Yamazaki, Naito, Shinohara, Fujiwara and Kikuchi3,Reference Ishikawa, Kawamata, Kawashima, Yamaguchi, Kubo and Hori5–Reference Santucci, Garber, Ivory, Kuhn, Stephen and Aizenberg26 The key findings of the literature review are summarised below, and within Tables 2 and 3.

Fig. 3. Literature review outcome, illustrated in the format of a Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) flow diagram.

Table 2. Literature review results showing identified causes of rapidly progressive hearing loss occurring over weeks

Hearing loss severity definitions: normal = 20 dB HL or lower; mild = 21–40 dB HL; moderate = 41–60 dB HL; severe = 61–90 dB; and profound over 90 dB HL. *The extent to which sarcoidosis contributed to the conductive aspect of the hearing loss is unknown.Reference Colvin20 F = initial presenting complaint; C = can be the initial presenting complaint; P = part of the initial presenting complaints; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

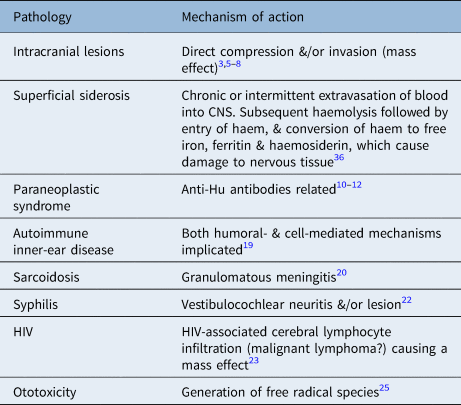

Table 3. Current opinions on pathophysiology of some identified causes for rapidly progressive hearing loss occurring over weeks

CNS = central nervous system; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

Prevalence of rapidly progressive hearing loss

The exact prevalence of patients presenting with rapidly progressive hearing loss is unknown. The limited search result reflects the uncommon nature of the presentation (Figure 3). Kishimoto et al. retrospectively reviewed cases of bilateral progressive SNHL over a five-year period, and found that 1.32 per cent of cases presented with rapidly progressive hearing loss (12 out of 908).Reference Kishimoto, Yamazaki, Naito, Shinohara, Fujiwara and Kikuchi3

Patient presentation

Rapidly progressive hearing loss can present as either unilateral or bilateral hearing loss. Both sequential and simultaneous onsets of bilateral rapidly progressive hearing loss have been reported in the literature. All reported cases of rapidly progressive hearing loss were sensorineural in nature (Table 2).Reference Kishimoto, Yamazaki, Naito, Shinohara, Fujiwara and Kikuchi3,Reference Ishikawa, Kawamata, Kawashima, Yamaguchi, Kubo and Hori5–Reference Santucci, Garber, Ivory, Kuhn, Stephen and Aizenberg26

Rapidly progressive hearing loss can present as an isolated symptom or as part of a constellation of symptoms, either as an initial presenting feature, or preceded by other manifestations of systemic disease (Table 2). When rapidly progressive hearing loss is the first presenting symptom of systemic disease, often further symptoms subsequently develop within weeks (Table 2).

Causes of rapidly progressive hearing loss

The underlying causes identified for rapidly progressive hearing loss are outlined in Table 2. They can be broadly categorised into: iatrogenic (medication-induced), paraneoplastic, inflammatory or autoimmune, infective, and intracranial or skull base lesion related. Inflammatory and autoimmune aetiologies were the most common causes associated with rapidly progressive hearing loss. All intracranial and skull base lesions, malignant or benign in nature, were associated with high patient mortality and morbidity.Reference Kishimoto, Yamazaki, Naito, Shinohara, Fujiwara and Kikuchi3,Reference Ishikawa, Kawamata, Kawashima, Yamaguchi, Kubo and Hori5–Reference Hausmann, Hausmann, Probst and Gratzl9

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiologies of rapidly progressive hearing loss are summarised in Table 3.

The pathophysiology of autoimmune inner-ear disease is thought to have both humoral- and cell-mediated mechanisms.Reference Mijovic, Zeitouni and Colmegna19 In autoimmune inner-ear disease, damage to the cochlea and its nerve has been associated with unilateral or bilateral loss, which can be either sequential or simultaneous. Often the hearing loss will fluctuate.Reference Mijovic, Zeitouni and Colmegna19 The vestibular organ and vestibular nerves are commonly affected; therefore, vestibular symptoms are commonly associated with autoimmune inner-ear disease.Reference Mijovic, Zeitouni and Colmegna19 It has been reported that up to one-third of autoimmune inner-ear disease cases occur in the context of a systemic autoimmune disease.Reference Mijovic, Zeitouni and Colmegna19

When considering the pathophysiology of rapidly progressive hearing loss as a result of an intracranial pathology, there are reports of both benign and malignant skull base lesions as the underlying cause (Table 2). Malignant lesions can be either primary tumours or distant metastases.Reference Kishimoto, Yamazaki, Naito, Shinohara, Fujiwara and Kikuchi3,Reference Ishikawa, Kawamata, Kawashima, Yamaguchi, Kubo and Hori5–Reference Zhang, Zhao, Sa, Qin, Qu and Wang8 Rapidly progressive hearing loss is more commonly associated with malignant neoplasms.Reference Kishimoto, Yamazaki, Naito, Shinohara, Fujiwara and Kikuchi3,Reference Ishikawa, Kawamata, Kawashima, Yamaguchi, Kubo and Hori5–Reference Zhang, Zhao, Sa, Qin, Qu and Wang8

The rapid onset of hearing loss as a result of a malignant neoplasm contrasts with the onset of hearing loss due to a benign tumour. The most common benign neoplasms that cause hearing loss are vestibular schwannomas.Reference Sunwoo, Jeon, Park, Song, Song and Choi27 Evidence suggests that the majority of vestibular schwannoma cases present with a chronic progressive hearing loss occurring over months to years, and 3–8 per cent present as sudden SNHL (onset of less than 72 hours).Reference Samii and Matthies28,Reference Foley, Shirazi, Maweni, Walsh, Walsh and Javadpour29 This may be explained by malignant lesions having a higher propensity to progress at a faster rate, resulting in a more rapid onset of hearing loss.Reference Ishikawa, Kawamata, Kawashima, Yamaguchi, Kubo and Hori5

Mangham et al. suggest that rapidly progressive hearing loss is a characteristic feature of cavernous haemangioma of the internal acoustic meatus (IAM).Reference Mangham, Carberry and Brackmann30 A more recent literature review presents contrasting evidence that these vascular malformations can present with hearing loss that is sudden, rapidly progressive or insidious in onset.Reference Mastronardi, Carpineta, Cacciotti, Di Scipio and Roperto31

Infectious causes of rapidly progressive hearing loss include cryptococcal and chronic herpes meningitis. These conditions are thought to cause rapidly progressive hearing loss through direct inflammation of the vestibulocochlear nerve, and through the formation of meningeal granulomas.Reference Chrétien, Lortholary, Kansau, Neuville, Gray and Dromer32,Reference Tyler33 Both forms of meningitis are associated with high patient mortality and long-term morbidity if not diagnosed and treated early.Reference Tyler33,Reference Pasquier, Kunda, De Beaudrap, Loyse, Temfack and Molloy34

Superficial siderosis is a rare pathology caused by chronic or intermittent extravasations of blood into the subarachnoid space, with a subsequent haemolysis and dissemination of haem by the circulating cerebrospinal fluid.Reference Koeppen, Michael, Li, Chen, Cusack and Gibson35 The deposited haem undergoes conversion into free iron, ferritin and haemosiderin, which in turn causes damage to the surrounding nerve tissues.Reference Koeppen, Michael, Li, Chen, Cusack and Gibson35 The vestibulocochlear nerve has been found to be particularly vulnerable.Reference Koeppen, Michael, Li, Chen, Cusack and Gibson35 The most common clinical presentation is slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia associated with hearing impairment. However, rapidly progressive hearing loss with or without vestibular symptoms can be the initial presenting symptom.Reference Kumar36 Early diagnosis and appropriate management has been shown to prevent further deterioration.Reference Kumar36

Medication-induced rapidly progressive hearing loss is the result of ototoxic side effects. This is believed to be dose-dependent and cumulative in nature.Reference Schacht, Talaska and Rybak25,Reference Santucci, Garber, Ivory, Kuhn, Stephen and Aizenberg26,Reference Selimoglu37 Symptoms can develop days to weeks after the commencement of drug therapy. Cisplatin and aminoglycoside antibiotics are the two most widely implicated ototoxic medications.Reference Schacht, Talaska and Rybak25,Reference Selimoglu37 Hearing loss as a result of their administration is reported to begin at high frequencies, extending to lower frequencies with prolonged treatment.Reference Schacht, Talaska and Rybak25 Santucci et al. suggest that patients undergoing platinum-based chemotherapy should have their hearing monitored pre-, peri- and post-treatment.Reference Santucci, Garber, Ivory, Kuhn, Stephen and Aizenberg26

Discussion

Clinical approach

The NICE defines rapidly progressive hearing loss as that occurring over 4–90 days.4 They advise urgent referral to otolaryngology or audiovestibular medicine departments on a two-week pathway, after ruling out any external and/or middle-ear causes.4

Our literature review findings fully support the NICE guidance. Most causes were either systemic or sinister in nature. The consequences of delayed management include a high risk of increased patient morbidity and mortality (Table 2).

When considering the underlying causes identified for rapidly progressive hearing loss and their presentations, we recommend undertaking a multi-system review. Within the history-taking, events in the weeks preceding presentation should be explored in detail. Specifically, systemic, neurological, ocular, audiovestibular, and head and neck ‘red flag’ symptoms should be screened for (Figure 4). A review of current and historical medications is recommended to identify any recently commenced or completed courses of ototoxic medications.

Fig. 4. Suggested algorithm for approaching a patient presenting with rapidly progressive sensorineural hearing loss. FBC = full blood count; U&Es = urea and electrolytes; ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; MRI IAM = magnetic resonance imaging of the internal auditory meatus; CT = computed tomography

Otological, cranial nerve and peripheral neurological examinations should be undertaken as a minimum. Examination of the skin to identify lesions (e.g. cutaneous vasculitis or erythema nodosum) associated with autoimmune or inflammatory conditions would be prudent. A pure tone audiometry should be performed to establish the nature and severity of the hearing loss, and to establish a baseline for monitoring purposes. Blood tests should be obtained, including: assessments of serum angiotensin-converting enzyme and calcium levels for sarcoidosis, an autoantibody screen for autoimmune disorders including vasculitis, a syphilis screen, and human immunodeficiency virus serology. An urgent magnetic resonance imaging scan of the IAM and the brain should be performed to rule out intracranial neoplasms. Imaging of the thorax in the form of a plain radiograph or computed tomography can be of benefit to screen for pulmonary sarcoidosis and/or lung cancer. High clinical suspicion is key, as non-invasive investigations lack sensitivity and specificity for some differential diagnoses such as sarcoidosis.Reference Pawate, Moses and Sriram38 Further investigations may be necessary as clinically suspected.

In all cases, the definitive management should be treatment of the underlying cause. It would be prudent to involve other specialties as early as clinically suspected (e.g. neurology and/or rheumatology). An initial trial of corticosteroids (1 mg/kg per day) whilst investigating the patient may be reasonable, considering that most differential diagnoses are autoimmune or inflammatory in nature (including possible oedema from an intracranial tumour) (Table 2). Furthermore, considering the known morbidity and mortality associated with certain differential diagnoses for rapidly progressive hearing loss, it may be reasonable to admit the patient for investigation and management, as clinically suspected (Table 2).

• Rapidly progressive hearing loss, an uncommon presentation, is defined as a hearing loss occurring over 4–90 days

• The condition is often due to systemic or sinister causes; delayed management increases risks of patient morbidity and mortality

• Rapidly progressive hearing loss should be considered a ‘red flag’ symptom and acted on urgently

• Hearing loss can be reversed in some cases following prompt and correct management of underlying pathology

There are documented cases of rapidly progressive hearing loss that were reversible when treated correctly and promptly (Table 2). Hearing rehabilitation using cochlear implantation can be an option for profound rapidly progressive hearing loss that is refractory to medical therapies. Successful implantations have been reported in some cases of rapidly progressive hearing loss resulting from ototoxic medication and sarcoidosis.Reference Ho, Vrabec and Burton24,Reference Svrakic, Golfinos, Zagzag and Roland39

Conclusion

Rapidly progressive hearing loss occurring over weeks should be considered a red flag symptom and acted on without delay. We recommend consideration of the immediate initiation of systemic corticosteroids and simultaneous urgent investigation of the underlying cause. The majority of pathologies associated with rapidly progressive hearing loss are either systemic or sinister in nature; therefore, delayed management increases the risk of patient morbidity and mortality.

Competing interests

None declared