Introduction

Migraines are very common and can present with a wide variety of aura symptoms and also additional symptoms related to the main headache phase. This wide variety of symptoms is indicative of the complex underlying pathophysiology.1–Reference Lipton, Bigal, Diamond, Freitag, Reed and Stewart5 Extensive research has associated the headaches primarily with the trigeminal-cervical complex, which, through the connections of the trigeminal nerve, can explain the distribution of the headaches as well as additional, commonly seen symptoms such as cutaneous allodynia.1–Reference Silberstein3

The involvement of other cranial nerves, particularly the ones with close proximity to the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerves IV and VI), has been described, and a strong link between the vestibular system and migraines (vestibular migraine) has recently been recognised by the Headache and Barany Society as an entity.Reference Stolle, Holle, Naegel, Diener and Obermann4,Reference Kontorinis, Tyagi and Crowther6 The involvement of the facial nerve in migraine attacks has been poorly described and is not really covered in the literature.

Idiopathic facial nerve palsy, widely known as Bell's palsy, is the commonest cause of facial nerve weakness with an incidence of 20 in 100 000. Interestingly, although up to 10–15 per cent of patients with Bell's palsy will develop a second episode, the risk of more than two recurrences is much lower, involving only 1.5 per cent of patients with facial nerve palsy.Reference English, Stommel and Bernat7 Recurrent facial nerve palsy has been associated with a few rare conditions, including Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome, Lyme's disease and autoimmune disorders.Reference Bauer and Coker8,Reference Zachariah and Patel9 However, further associations and the precise underlying mechanisms have been poorly understood. In 2003, a case report raised the possibility of facial nerve palsy as part of migraines.Reference Zachariah and Patel9 However, further reports are missing.

In this study, our objective was to assess cases of recurrent facial nerve palsy and determine whether there could be any association with underlying migraines.

Materials and methods

Basic settings and patient selection

This prospective, observational study was carried out in an academic, tertiary referral centre over a two-year period. The Departmental Ethical Board granted ethical approval for this study.

We recruited all patients referred to our neurotology service with recurrent facial nerve palsy, defined as four or more documented episodes.

We excluded all patients who had: (1) experienced less than four episodes of facial nerve palsy in order to avoid inclusion bias (because many patients with two or three episodes can be seen in general clinics without tertiary input); (2) permanent facial nerve palsy; (3) a history of skull base tumours or skull base pathologies that could explain the episodes of facial nerve palsy; (4) undergone surgical procedures and developed facial nerve palsy as a result of these (iatrogenic causes); and (5) neurofibromatosis type II, which is a known syndromic cause of a potential facial nerve palsy.

All patients underwent the same diagnostic tests and were followed for two years after the initial presentation to the clinic. All patients were treated with high-dose oral steroids at the time of the episode(s) with further treatment tailored to the final diagnosis.

Patient diagnostics and included factors

All enrolled patients underwent a standardised protocol of diagnostic tests based on the existing literature, including a detailed medical history with history of migraines, a thorough clinical examination including neurotological examination, parotid and neck palpation, imaging studies, hearing assessment (pure-tone audiometry, tympanometry and stapedial reflex), and serology and blood tests.

All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the internal auditory meatus and the brain, including a 1.5 Tesla fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition (‘FIESTA’) MRI, and a T1-weighted MRI, both with and without intravenous gadolinium administration to rule out multiple sclerosis and lesions across the route of the facial nerve. MRI was performed at least three months after the last episode of facial nerve palsy to avoid misinterpreting enhancement of the facial nerve due to neuronitis such as in a neoplastic process. We also performed computed tomography of the temporal bones (0.5–0.625 mm thickness with reconstruction in the axial, coronal and sagittal plane) to rule out a middle-ear, osseous abnormality.

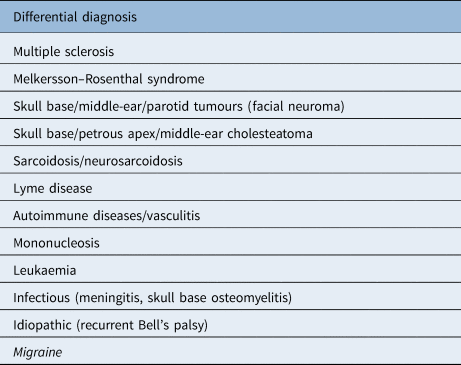

Blood tests and serology included tests for full blood count, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte segmentation rate, mononucleosis test, urea and electrolytes, glucose, bone profile including vitamin D, vitamin B complex, angiotensin converting enzyme (for sarcoidosis), vasculitis screening and Borrelia Burgdorferi serology (Lyme disease). Lumbar puncture was only to be performed within the appropriate clinical context. Table 1 presents the commonest causes of recurrent facial nerve palsy. Additionally, we recorded demographic factors (age, gender), age at the initial episode, side(s) of facial nerve palsy, number of episodes and final facial nerve function (using the House–Brackmann grading scaleReference House and Brackmann10) and any additional medication apart from oral steroids.

Table 1. Commonest differential diagnoses of recurrent facial nerve palsy

Migraine is highlighted in italics given the lack of references

Results

Four patients with more than four episodes of facial nerve palsy meeting the inclusion criteria were identified. They were all female with an average age at referral of 40.75 years (range, 33–60 years) and an average age at the initial episode of 14 years (range, 12–16 years). They were all followed for two years for the requirements of this study. The number of episodes varied between six and nine episodes. Although most of the episodes were predominantly affecting one side, all patients had at least one episode of facial nerve palsy on the contralateral side (Table 2).

Table 2. Detailed data of the enrolled patients

All patients were female. FNP = facial nerve palsy; HB = House–Brackmann; M-RS = Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome; FN = facial nerve

Patient 1 was diagnosed with Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome as she additionally presented with recurrent swelling of the lips. She underwent facial nerve decompression on the more severely affected side due to poor recovery on oral steroids following her third severe facial nerve palsy within six months and achieved a good outcome. She had no history of migraines.

Patient 2 remains without a definite diagnosis despite extensive diagnostic tests. Her facial nerve function is normal, and she has been without any episodes for 12 months. Enhancement of the facial nerve shown at the initial MRI showed facial neuronitis, which had dissolved on serial imaging three months later. She had no clear history of migraines. However, she could not give detailed history from her childhood and she did not rule out headaches in her childhood. She remains under review.

The last two patients (patients 3 and 4) had no abnormalities in the detailed screening. They had experienced three episodes within the last six months prior to the referral. Patient 3 had a residual mild unilateral weakness of the facial nerve that was visible only on active movements (grade 2). They both had a history of migraines with aura that were treated with medication as required. The episodes of facial nerve palsy were associated with headaches that fulfilled the International Headache Society criteria for migraine (unilateral headaches of pulsatile quality). Both patients were started on prophylactic treatment for migraines. The headaches gradually subsided and both patients have not had any further episodes of facial nerve palsy since (one year following the start of treatment for migraine; Table 2).

Discussion

We present rare cases of recurrent facial nerve palsy, related diagnostic tests and diagnoses. This is the first report on the possible association of recurrent facial nerve palsy and migraines, which despite the limited numbers, highlights such a hypothesis in a two-year-observation set-up. So far, to our knowledge, there has been only one case report on a patient with migraines and recurrent facial nerve palsy.Reference Zachariah and Patel9 With thorough diagnostic tests ruling out other causes, the chronological link between the migraines and the facial nerve palsy and the improvement of the headaches and prevention of further episodes of facial nerve palsy following prophylactic medication for migraines favours such a hypothesis. Additionally, we provide a brief but still detailed description of the recommended diagnostic tests in patients with recurrent facial nerve palsy based on the existing literature and alternative diagnoses.

Possible mechanisms behind facial nerve palsy in migraines

The trigeminal-cervical complex provides adequate background to the mechanism and the wide variety of pain distribution in migraine, while studies using up-to-date techniques, including functional MRI have shown increased activity in certain parts of the brain prior to the initiation of the headaches that help us understand the prodromal or aural symptoms.Reference Schwedt, Chiang, Chong and Dodick11 With respect to the involvement of cranial nerves, the close proximity of the trigeminal nerve to certain structures such as the cavernous sinus and the nearby cranial nerves provides sufficient explanation of symptoms related to temporary dysfunction of such nerves.1–Reference Stolle, Holle, Naegel, Diener and Obermann4 However, given the lack of studies investigating the possible association of recurrent facial nerve palsy and migraines, little is known in this domain.

• Recurrent facial nerve palsy is rare and under-investigated in the existing literature

• Thorough testing batteries including clinical and audiological assessment, blood and immunology tests and imaging studies are essential

• In certain patients, the recurrent facial nerve palsy can be related to underlying migraines; these patients respond well to prophylactic medication for migraines

• In recurrent facial nerve palsy, there appears to be a dominant side; however, similar to the pattern of headaches in migraines, the contralateral side can also be affected

Connections between the facial and the trigeminal nerve have been described; such connections can explain and also strengthen the potential involvement of the facial nerve in patients suffering from migraines. The connection through the superficial petrosal nerve is anatomically described by Gupta and perhaps explains how facial nerve palsy could be associated with migraine.Reference Gupta12 Although our study included only patients with a large number of recurrent facial nerve palsy episodes, it is a reasonable and valid hypothesis that patients with either two or only one episode of facial nerve palsy who have been diagnosed with ‘Bell's palsy’ without further investigation are actually suffering from migraines, with the facial nerve palsy being part of their migraines. Similar observations led to the relatively new diagnosis of vestibular migraine;Reference Stolle, Holle, Naegel, Diener and Obermann4,Reference Kontorinis, Tyagi and Crowther6 the possibility of a ‘facial migraine’, given our findings and the well-known connections between the trigeminal and the facial nerve, is not irrational.

The residual mild weakness in one of our patients highlights the difference in nature of the primarily motoric facial nerve and other involved sensory nerves, and it is usually difficult to determine the recovery of these motor nerves. As an example, cutaneous allodynia, as part of migraines, is usually recurrent and sometimes present even between attacks, indicating incomplete recovery of the involved trigeminal branches.Reference Dodick2,Reference Silberstein3 Additionally, the recurrence of facial nerve palsy can be explained by the neural memory that has been described in migraines; once a conduction pathway has been established, repetition can occur resulting in recurrent palsies.Reference Gupta12,Reference Lance and Zagami13

Finally, the predominant but not solely unilateral character of facial nerve palsy in the two patients with migraines is in agreement with the nature of headaches in many patients with migraines because such a headache can, in some patients, change side even within the same episode of the migraine.Reference Dodick2,Reference Kelman14

Strengths and limitations

The small number of enrolled individuals is the main weakness of the present study. However, identifying patients with a proven large number of recurrent facial nerve palsy episodes and assessing and observing them in a prospective, structured manner is a challenge. We utilised a robust follow up system and thorough investigations to overcome this weakness and provide accurate data in this brief report.

Long-term follow up of the presented cases, which is ongoing in our unit, will provide us with better understanding and overview of the prognosis and whether facial nerve palsy should be considered a possible expression of a migraine. Finally, identifying and assessing patients who have only suffered one or even two episodes of facial nerve palsy in prospective, observational settings should show the possible link between migraines and facial nerve palsy, eliminate the current limitations and improve our understanding and treatments. Taking a thorough patient history and awareness that facial nerve palsy could potentially be related to migraines by the general medical community is required.

The present study raises the possibility of an association between true recurrent facial nerve palsy and migraines. Awareness in the health community and more detailed investigations in patients with even fewer episodes of facial nerve palsy should be able to confirm such an association.

Competing interests

None declared