Introduction

Pharyngeal pouch, also known as Zenker's diverticulum, is a pulsion diverticulum occurring between the inferior constrictor and cricopharyngeus muscles. It occurs mainly in the older population, and has an estimated incidence of approximately 1 per 100 000 per year. Although traditionally treated by open neck surgery, endoscopic techniques have now become standard first-line treatment, with the hypopharyngeal bar being divided using carbon dioxide laser or stapling.1, Reference Sen, Lowe and Farnan2

In 2003, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) published an interventional procedure overview of endoscopic stapling of pharyngeal pouches.1 Based on retrospective case series published between 1998 and 2002, endoscopic stapling appeared to enable faster recovery than open surgery, but was not without complications, such as conversion to open procedure, perforation and repeat procedures. Specialist advisors recommended that endoscopic stapling should be performed by super-specialists in the procedure, rather than by all otolaryngologists.1

In 2002, Mirza et al. advised that elderly and frail patients with symptomatic pharyngeal pouches to whom general anaesthetic posed a risk may benefit from endoscopic stapling.Reference Mirza, Dutt, Minhas and Irving3 Casso et al. (2006) and Lieder et al. (2008) concluded that endoscopic stapling gave best results in patients with moderate or large pouches.Reference Casso, Lalam, Ghosh and Timms4, Reference Lieder, Nasseri, Sharma and Jani5 Krespi et al. (2002) and Hoffman et al. (2003) noted that endoscopic CO2 laser surgery was useful for small pouches.Reference Krespi, Kacker and Remacle6, Reference Hoffmann, Scheunemann, Rudert and Maune7 The endoscopic laser technique also had the advantage of providing better access compared with endoscopic stapling. The 2005 Cochrane review of surgical interventions for pharyngeal pouch concluded that there was no good evidence to establish any one endoscopic procedure as superior to others.Reference Sen, Lowe and Farnan2 There was also no evidence from high quality randomised trials to demonstrate the effectiveness of endoscopic versus open procedures for pharyngeal pouch.Reference Sen, Lowe and Farnan2

The aim of this study was to evaluate the results of endoscopic surgical management of patients with pharyngeal pouches in north Glasgow, in terms of complications, resolution of symptoms, morbidity and repeat procedures, and also to assess our practice in relation to NICE recommendations.

Materials and methods

A retrospective review of case notes and surgical records was performed for consecutive patients who had undergone pharyngeal pouch surgery between 1998 and 2008 in north Glasgow, Scotland, UK. We identified a total of 100 patients, who were operated upon by eight consultant otolaryngologists. All pharyngeal pouches were diagnosed by barium swallow studies. Patients' case notes were reviewed for patient demographics, American Society of Anesthesiologists anaesthetic assessment grading, surgical procedure type, complications, outcomes, and management of abandoned procedures and recurrences. Patients' post-operative symptoms were graded as worse, no change, little improvement or significantly better, by subjective assessment of case note entries.

Results

Between 1998 and 2008, 100 patients underwent pharyngeal pouch procedures. Fifty-eight patients were male and 42 female. Patients' mean age at surgery was 70 years (range 36 to 89 years). American Society of Anesthesiologists gradings of one, two and three were given to 26, 48 and 24 per cent of the patients, respectively. Eighty-eight patients underwent primary pharyngeal pouch surgery, while 12 patients had undergone previous pharyngeal pouch surgery prior to 1998 or at another centre.

Primary group

Type of surgery

Of the 63 patients for whom endoscopic stapling was attempted, a successful result was achieved in 55 (Table I). Twenty patients underwent endoscopic CO2 laser surgery. Of the remaining primary group, two patients underwent pharyngoscopy with dilatation. External approaches were used in three patients: one underwent external excision of the pharyngeal pouch with cricopharyngeal myotomy, and two underwent cricopharyngeal myotomy alone.

Table I Pharyngeal pouch surgery: primary group

*One patient underwent pharyngeal pouch excision two years later. †This patient had a second revision stapling procedure. Pts = patients; CM = cricopharyngeal myotomy

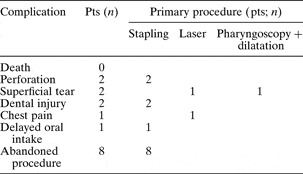

Complications

There was no mortality. We identified two cases of perforation due to the endoscopic stapling procedure. Dental injuries (two patients), superficial tears (two) and delayed oral intake (one) were reported. There were no reported instances of mediastinitis or vocal fold palsy. The complications associated with the primary group surgical procedures are shown in Table II.

Table II Pharyngeal pouch surgery complications: primary group

Pts = patients

Abandoned endoscopic surgery

There were eight cases in which endoscopic stapling was attempted but abandoned. The abandoned procedure rate for endoscopic stapling was 12.7 per cent (eight of 63). Only five of these eight patients decided to proceed with further surgery. No endoscopic CO2 laser procedures were abandoned.

Revision surgery

Of the 55 patients undergoing successful endoscopic stapling, seven required revision endoscopic stapling. Details of revision surgery procedures are shown in Table I. The revision endoscopic stapling rate, following successful stapling, was 12.7 per cent. The potential revision rate for endoscopic stapling, taking into consideration patients whose previous endoscopic stapling procedure had been either successful or abandoned, was 23.8 per cent (15/63); however, because three patients declined further procedures after abandoned endoscopic stapling, 19 per cent (12/63) of the endoscopic stapling cohort underwent further surgery. Following endoscopic laser surgery, four patients required revision surgery (three had endoscopic laser surgery, one had endoscopic stapling). The revision rate for endoscopic laser surgery was 20 per cent.

Length of stay

The average length of stay for patients undergoing successful endoscopic stapling was 1.7 days. This figure excluded the two cases of iatrogenic perforation. The lengths of stay for the two patients who had a perforation following endoscopic stapling were 11 and 13 days, variously. Sixty per cent of endoscopic stapling patients were discharged on the first post-operative day, and 74.5 per cent by the second post-operative day. The average length of stay for patients undergoing endoscopic CO2 laser surgery was 3.3 days. Ten per cent of endoscopic laser surgery patients were discharged on the first post-operative day, and 50 per cent by the second post-operative day. For patients undergoing external approach procedures, the average length of stay was 3.7 days.

Resolution of symptoms

Symptom outcome data were available for 65 (73.9 per cent) patients. Seven patients were discharged post-operatively without follow up. Of patients for whom follow-up appointments were arranged, nine had no documentation of any such follow up. Seven case notes had been destroyed. At six to eight weeks' follow up, 50 (76.9 per cent) patients reported much better swallowing, six (9.2 per cent) stated that their swallowing was ‘a little better’ and eight (12.3 per cent) reported no change in their swallowing symptoms since their primary procedure. No patient reported worse swallowing since surgery. Sixty per cent of patients who had undergone endoscopic CO2 laser surgery, and 63.6 per cent of those who had undergone endoscopic stapling, reported much better swallowing.

Previous surgery group

This group of patients presented rather varied characteristics. In this heterogeneous group, 12 patients had undergone previous pharyngeal pouch surgery before 1998, of which two-thirds had undergone at least two previous surgical procedures. Between 1998 and 2008, endoscopic stapling was successfully performed in three patients, but had to be abandoned in two patients, who subsequently underwent successful endoscopic stapling (Table III). At our institution, endoscopic laser surgery was the commonest surgical procedure amongst patients previously undergoing pouch surgery, being conducted in six patients. One patient underwent pharyngoscopy and dilatation.

Table III Pharyngeal pouch surgery: previous surgery group

Pts = patients

Regarding complications, two patients had stapling procedures abandoned due to a difficult surgical view, but stapling was successfully conducted on subsequent attempts. One patient's revision laser surgery was abandoned as the cricopharyngeal mucosal bar was deemed too small to laser without significant risk of perforation. Delayed oral intake was observed in one patient. During the study period, three patients reported much improvement in swallowing after the first procedure, while four patients required a second procedure to yield improvement in swallowing.

Discussion

Options for surgical management of pharyngeal pouch may be divided into two main categories: endoscopic approach and external approach. Endoscopic procedures involve division of the cricopharyngeal bar, with the use of laser or stapling to create a single lumen. Cricopharyngeal myotomy takes place simultaneously. External approaches include pouch suspension, pouch inversion, cricopharyngeal myotomy, and excision of the pouch with cricopharyngeal myotomy. Endoscopic techniques are now standard first-line treatment for pharyngeal pouch, as they are safer and enable faster recovery and earlier resumption of oral intake. The procedure may also be repeated for persistent or recurrent symptoms.1

The present series provided an overview of the surgical techniques employed in the management of pharyngeal pouch in north Glasgow. It currently represents the largest pharyngeal pouch surgery series reported in the UK. Eight otolaryngology consultants performed the pharyngeal pouch surgery. Endoscopic approach techniques predominated, namely CO2 laser and stapling. One surgeon used only the external approach, and another only the CO2 laser technique. The remaining six surgeons used endoscopic stapling as the first-line procedure.

In analysing our results, we distinguished between patients undergoing primary pharyngeal pouch surgery and patients who had had previous pharyngeal pouch surgery before the study period. This allowed a more accurate and relevant assessment of the complications, incidence of procedure abandonment and surgical outcome. Earlier published series do not appear to clearly state whether their patients had undergone previous pharyngeal pouch surgery or not.

Complications resulting from an endoscopic approach include perforation, mediastinitis, vocal fold injury, dental injury and glottic oedema. In our study, there were two cases (2.9 per cent; two of 68) of iatrogenic perforation from endoscopic stapling. Both were conservatively managed, and water-soluble contrast studies performed on the eighth post-operative day showed that the perforations had healed. Perforation rates quoted in previously published endoscopic stapling series range from 1.4 to 14.6 per cent.Reference Mirza, Dutt, Minhas and Irving3, Reference Lieder, Nasseri, Sharma and Jani5, Reference Visosky, Parke and Donovan8

A total of 11 attempted endoscopic stapling procedures were abandoned intra-operatively, involving 10 patients; one patient had two attempts at endoscopic stapling and declined further surgical treatment. Our incidence of endoscopic stapling abandonment (16 per cent; 11/68 (both primary and previous surgery patients)) was high compared with other published series (10.3–13.9 per cent).Reference Mirza, Dutt, Minhas and Irving3, Reference Visosky, Parke and Donovan8 The main reason for procedure abandonment was poor access due to dentition (seven of 10 patients), followed by spinal deformity. Thus, pre-operative assessment of patients for diverticuloscope access is important, especially for those with prominent dentition, large tongue or retrognathic mandible. In future, such patients should be more appropriately counselled regarding the potential success rate of the procedure.

Repeat procedures for persistent or recurrent symptoms were carried out in 13 patients. Seven patients who had undergone primary endoscopic stapling required further revision stapling, and six patients required further revision endoscopic laser surgery. Five patients had repeat endoscopic procedures within 12 months. Our average time from first procedure to revision procedure was 15 months. Our incidence of repeat endoscopic procedures was 15.4 per cent, assessing patients whose initial endoscopic procedures (during the study period) had been successful. If we also include cases of abandoned endoscopic procedures which were followed by further endoscopic procedures, then the repeat endoscopy incidence would be 21.3 per cent. Previously published series have reported incidences ranging from 12 to 32 per cent.Reference Mirza, Dutt, Minhas and Irving3, Reference Lieder, Nasseri, Sharma and Jani5, Reference Visosky, Parke and Donovan8

In the UK, endoscopic stapling is more frequently used than endoscopic laser surgery.1, Reference Mirza, Dutt, Minhas and Irving3 The most recent UK series of cases undergoing endoscopic laser surgery for pharyngeal pouch management was published in 1997.Reference Bradwell, Bieger, Stranchan and Homer9 In our institution, endoscopic laser surgery was used for pharyngeal pouch treatment in 26 per cent of patients over the study period. These 26 patients represent the largest UK-reported case series of endoscopic laser diverticulotomy for pharyngeal pouch to date. Endoscopic laser surgery also appeared to be used preferentially in patients who had previously undergone pharyngeal pouch surgery but who were experiencing recurrent or persistent symptoms.

We found the laser technique useful when there was a poor view of the pouch after the stapling gun had been inserted, or when the pouch was too small to permit safe use of the stapling gun. Previous studies have reported that the difficulty with laser division lies in determining the point at which laser division of the party wall should end, as too shallow a division will lead to persistence of symptoms while too deep a division risks perforation with mediastinitis.Reference Gutschow, Hamoir, Rombaux, Otte, Goncette and Collard10 Other concerns included troublesome bleeding and thermal injury. Although a number of studies have reported that endoscopic stapling is safer compared with endoscopic laser, we observed no major complications with the use of endoscopic laser technique in our patients.Reference Mirza, Dutt, Minhas and Irving3, Reference Miller, Bartley and Otto11 We also note that previously reported studies compared only a small sample of endoscopic laser cases.Reference Miller, Bartley and Otto11

A particular feature of the practice of our surgeons performing endoscopic laser surgery was that a significant proportion of dentate patients undergoing endoscopic stapling used custom-made, laser-resistant dental guards peri-operatively (as compared with the standard soft, silicone bite guard (Medasil; (Surgical) Ltd, Leeds, England). This may be one reason why no dental injury was reported in the endoscopic laser cohort. Furthermore, no first endoscopic laser procedures (conducted during the study period) were abandoned. These results appear to support the practicality and efficacy of custom-made dental guards for all dentate patients undergoing trans-oral endoscopic procedures for pharyngeal pouches.

There was no significant difference in the repeat procedure rate, comparing laser technique (23 per cent) and stapling technique (21 per cent). Four of the six patients requiring revision laser diverticulotomy were reported to have large pharyngeal pouches on their pre-operative barium swallow study. Our data appear to be in agreement with previous studies reporting better laser diverticulotomy outcomes in patients with smaller pharyngeal pouches.Reference Krespi, Kacker and Remacle6, Reference Hoffmann, Scheunemann, Rudert and Maune7

• This is the largest reported UK series of endoscopic pharyngeal pouch surgery cases

• Endoscopic CO2 laser treatment for pharyngeal pouch is useful in situations where introduction of a stapling gun results in poor access or a poor surgical view

• Custom-made dental guards are advisable for dentate patients undergoing transoral endoscopic pharyngeal pouch procedures

• Endoscopic pharyngeal pouch surgery should be undertaken only by otolaryngologists with a primary head and neck interest

The NICE interventional procedure overview of endoscopic stapling of pharyngeal pouch recommended that procedures should be performed by super-specialists in the procedure, rather than all ENT specialists.1 At the time of the current study, eight of the 10 otolaryngology consultants in the north Glasgow region performed pharyngeal pouch surgery. Our results also showed that we had higher incidences of abandoned and revised procedures, compared with previously published series. According to the NICE guidelines, it could be argued that there are too many generalist otolaryngology consultants performing endoscopic pharyngeal pouch surgery in north Glasgow. However, we noted that our complication rate was comparable with those of recent published series.

Are NICE recommendations therefore too restrictive, or are they somewhat outdated (based as they are on studies conducted at an earlier stage in the development of endoscopic stapling procedures)? It is perhaps important to note that NICE's interventional procedure overview applied only to endoscopic stapling; the recommendations did not concern other endoscopic techniques. From our findings, we suggest that it may be more sensible and effective to recommend that only otolaryngologists with a primary head and neck interest perform these endoscopic techniques. By having a tighter protocol for surgeons performing such endoscopic techniques, the rate of abandoned procedures may perhaps be improved.

Conclusion

Endoscopic procedures are now standard first-line treatment for surgical management of pharyngeal pouches. Both endoscopic stapling and laser techniques appear to be safe and effective. Assessment of diverticuloscope access is important, especially when preparing patients for endoscopic stapling. The endoscopic laser technique provides a good alternative to endoscopic stapling in cases with poor access, a small pharyngeal pouch or previous surgery. Custom-made dental guards may help reduce the risk of dental injury in dentate patients. As regards endoscopic technique preference, we feel justified in maintaining the two different techniques in the North Glasgow Otolaryngology Department, as each has its own merits and complements the other. As regards NICE recommendations, we consider that endoscopic pharyngeal pouch surgery should be undertaken only by otolaryngologists with a primary head and neck interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank all north Glasgow ENT consultants.