Introduction

Paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is a rare, heterogeneous and life-threatening condition. It is most commonly a complication of infective otomastoiditis, and frequently affects the lateral cerebral venous sinus. Further complications can be otological, neurological and ophthalmological.Reference Csákányi, Rosdy, Kollár, Móser, Kovács and Katona1–Reference Neilan, Isaacson, Kutz, Lee and Roland5

As highlighted by this case presentation, consensus for paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis management is desirable yet elusive given the paucity of available evidence. We discuss the management uncertainties that led to multidisciplinary discussion of this case, and the relevant evidence identified via a PubMed and Medline database search. We present our guidance for both assessment and management.

Case report

A previously well 2-year-old female in-patient, treated for acute mastoiditis with intravenous co-amoxiclav, was persistently pyrexial, then lethargic, 36 hours into her admission. She was scheduled for emergency surgery. A pre-operative computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated otomastoiditis, a subperiosteal abscess and a probable lateral cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was considered so as to confirm the thrombosis; this was eventually deemed unnecessary.

Surgery included myringotomy and ventilation tube insertion, abscess incision and drainage, and cortical mastoidectomy. During admission, referrals were made to numerous medical specialties. After several discussions, low-molecular-weight heparin anticoagulant treatment was initiated. Following in-patient discharge, the patient completed a three-month low-molecular-weight heparin course. She was followed up by the ENT surgery and neurology departments, with no interval imaging. She was discharged at six months, with no morbidity.

Discussion

Assessment

Paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis should be considered in children presenting with an otological inflammatory process (e.g. infection) and any of the following clinical features: headache, vomiting, behavioural disturbance, seizure, a reduced conscious level, focal neurological deficit(s) and raised intracranial pressure signs (e.g. papilloedema).

The following specialties should be involved in the assessment and management of suspected and confirmed paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: radiology, infectious diseases, ENT surgery, neurology, ophthalmology and haematology.

Radiology

When paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is suspected, confirmatory imaging is required via CT and/or MRI. Unenhanced CT is not recommended given its low sensitivity and specificity.Reference Ghoneim, Straiton, Pollard, Macdonald and Jampana6 Computed tomography venography demonstrates cerebral venous sinus thrombosis as a filling defect, with a sensitivity of 75–100 per cent.Reference Ferro, Bousser, Canhão, Coutinho, Crassard and Dentali7 It is superior to magnetic resonance venography in terms of acquisition time and (fewer) movement artefacts, and for bony anatomy.Reference Ferro, Bousser, Canhão, Coutinho, Crassard and Dentali7,Reference Leach, Fortuna, Jones and Gaskill-Shipley8

The MRI should be contrast-enhanced, as early thrombus (less than 5 days old) may be occult without it.Reference Leach, Fortuna, Jones and Gaskill-Shipley8 This relative insensitivity on unenhanced studies recurs when the thrombus is chronic (lasting for more than 15 days) because of variable recanalisation.Reference Ganeshan, Narlawar, McCann, Jones and Curtis9 Magnetic resonance imaging has no radiation exposure, it is better for characterising soft tissue changes, and it offers exclusive techniques that are useful in certain scenarios (e.g. diffusion-weighted imaging).Reference Ghoneim, Straiton, Pollard, Macdonald and Jampana6,Reference Leach, Fortuna, Jones and Gaskill-Shipley8,Reference Poon, Chang, Swarnkar, Johnson and Wasenko10,Reference Ravesh, Jensen-Kondering, Juhasz, Peters, Huhndorf and Graessner11 Magnetic resonance imaging is generally considered more sensitive and specific than CT.Reference Leach, Fortuna, Jones and Gaskill-Shipley8,Reference Khandelwal, Agarwal, Kochhar, Bapuraj, Singh and Prabhakar12 However, MRI is not always practical, especially for children. Computed tomography has lower yet acceptable sensitivity and specificity.Reference Ferro, Bousser, Canhão, Coutinho, Crassard and Dentali7,Reference Leach, Fortuna, Jones and Gaskill-Shipley8

There is no single ‘best’ imaging modality for all paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis cases. We recommend that modality selection be discussed with radiologists on an individualised basis. Re-imaging should be considered when imaging findings are negative for paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and clinical suspicion remains.

Management

Infectious diseases

Bacterial mastoiditis is a common cause of paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Classical pathogens include Haemophilus influenzae, streptococcus spp., staphylococcus spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Moraxella catarrhalis. Reference Laulajainen-Hongisto, Saat, Lempinen, Markkola, Aarnisalo and Jero13 There is an association between immune dysfunction or immaturity and an increased risk of developing bacterial mastoiditis.Reference Stergiopoulou and Walsh14 Immune dysfunctions require experience to suspect and diagnose them.

Infectious paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is more common with certain pathogens, especially Fusobacterium necrophorum.Reference Biesbroek, Wang, Keijser, Eijkemans, Trzciński and Rots15–Reference Gelbart, Bilavsky, Chodick, Raveh, Levy and Ashkenazi-Hoffnung17 Coudert and colleagues’ series found that F necrophorum related paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis tends to present in younger children with a more severe clinical presentation.Reference Coudert, Fanchette, Regnier, Delmas, Truy and Nicollas16 Furthermore, fusobacterium-related skull base osteomyelitis has been reported.Reference Khan, Quadri, Kazmi, Kwatra, Ramachandran and Gustin18

Having considered the potential complexities, we recommend referral to the infectious diseases department in all cases of paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Local antimicrobial prescribing guidance should be followed.

ENT surgery

Children with acute mastoiditis and paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis often require surgery.

Wong and colleagues’ systematic review of 174 surgical cases categorised procedures as either ‘conservative’ or ‘extensive’.Reference Wong, Hickman, Richards, Jassar and Wilson19 Conservative procedures included myringotomy, ventilation tube insertion, mastoidectomy, sinus needle aspiration and sinus decompression. Extensive procedures included thrombectomy and internal jugular vein (IJV) ligation. The most common surgery was cortical mastoidectomy with sinus decompression.Reference Wong, Hickman, Richards, Jassar and Wilson19

We conducted our own analysis of complications amongst the conservative and extensive groups. We excluded wound bleeding, haematoma, epistaxis and cellulitis, as these were not related to the extensiveness of surgery. The conservative post-operative complication rate was 0.8 per cent (1 out of 121 patients; ‘recurrent raised intracranial pressure’).Reference Bales, Sobol, Wetmore and Elden2 The extensive post-operative complication rate was 5.6 per cent (3 out of 53 patients). Extensive group complications included permanent visual impairment and temporal lobe herniation. Two of this group's three patients had IJV thrombosis; two underwent IJV ligation and all three underwent thrombectomy.Reference Csákányi, Rosdy, Kollár, Móser, Kovács and Katona1,Reference Megalamani, Ravi and Balasubramanian20,Reference Kaplan, Kraus, Puterman, Niv, Leiberman and Fliss21

Since Wong and colleagues’ review, there have been 2 more paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis published series, comprising 32 surgically managed children.Reference Coutinho, Júlio, Matos, Santos and Spratley22,Reference Scorpecci, Massoud, Giannantonio, Zangari, Lucidi and Martines23 They all underwent similar conservative surgical procedures; no thrombectomies or IJV ligations were performed. The post-operative complication rate was 0 per cent.

It is clear that conservative interventions are associated with lower post-operative complication rates (0.8 vs 5.6 per cent). It may be postulated that patients undergo more extensive surgery because of the extent of the thrombosis and severity of associated conditions. However, there are no published instances of complications where conservative surgery has been used in more extensive thromboses (e.g. IJV extension). Extensive surgical procedures are more likely to be responsible for post-operative complications than the underlying thrombosis characteristics.

We recommend conservative surgery (specifically mastoidectomy with or without myringotomy and ventilation tube insertion) in cases of paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and discourage extensive interventions.

Neurology

Neurological complications of paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis may include cerebral oedema, ischaemia, haemorrhage, dural arteriovenous fistula, intracranial hypertension, epilepsy and developmental delay.Reference Ghoneim, Straiton, Pollard, Macdonald and Jampana6,Reference Piazza24,Reference Tait, Baglin, Watson, Laffan, Makris and Perry25 Onset and presentations vary, and there is potential for severe morbidity and mortality.Reference Ghoneim, Straiton, Pollard, Macdonald and Jampana6.Reference Piazza24,Reference Tait, Baglin, Watson, Laffan, Makris and Perry25 Therefore, referral to the neurology department and subsequent follow up is recommended. Other aspects related to the neurology specialty are discussed in the ‘Haematology’ section below.

Ophthalmology

Existing literature regarding the assessment and management of ophthalmological sequelae in all-age, all-cause cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is limited. Yadegari et al. reported visual loss (30 per cent), diplopia (28 per cent), papilloedema (68 per cent), abducens nerve palsy (30 per cent) and proptosis (8 per cent) in their 53-adult patient series.Reference Yadegari, Jafari and Ashrafi26 There was association between the absence of visual loss or proptosis and a favourable outcome. There were no associations between the specific sinus affected and ocular manifestations.Reference Yadegari, Jafari and Ashrafi26 Proptosis strongly indicates cavernous sinus thrombosis.Reference Yadegari, Jafari and Ashrafi26,Reference Pollock, Kim, Sargent, Aroichane, Lyons and Gardiner27

Papilloedema incidence rates in all-age, all-cause cerebral venous sinus thrombosis range between 28 per cent and 90 per cent.Reference Novoa, Podvinec, Angst and Gürtler3,Reference Rosdy, Csákányi, Kollár, Móser, Mellár and Kulcsár4,Reference Vieira, Luis, Monteiro, Temudo, Campos and Quintas28–Reference Koitschev, Simon, Löwenheim, Kumpf, Besch and Ernemann30 In Liu and colleagues’ multicentre series of 65 patients with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis related papilloedema, 56 per cent had papilloedema on presentation, but its appearance was delayed in the remaining patients.Reference Liu, Bhatti, Chen, Fairbanks, Foroozan and McClelland31 Treatments were highly variable. Forty per cent of patients had permanent visual field defects; worsening papilloedema was significantly associated with this.

Paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis related papilloedema, and even more so proptosis, are associated with permanent visual complications. We recommend early referral of all cases of paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis to the ophthalmology department, with individualised follow up.

Haematology

The European Federation of Neurological Societies’ systematic review of adult all-cause cerebral venous sinus thrombosis recommended screening for thrombophilia.Reference Einhäupl, Stam, Bousser, De Bruijn, Ferro and Martinelli32 Conversely, and more specifically, multiple previous reports of paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis case series have included screening, with evidence that thrombophilia detection has no significant influence on outcomes.Reference Novoa, Podvinec, Angst and Gürtler3,Reference Dudkiewicz, Livni, Kornreich, Nageris, Ulanovski and Raveh33–Reference Zangari, Messia, Viccaro, Bottero, Randisi and Marsella36 There is also a financial cost. Whilst it is recognised that children with paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis may have underlying thrombophilia, this does not influence outcomes.

Anticoagulation in paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis has both been advocated and questioned. No previously reported series has been able to demonstrate a statistically significant benefit with anticoagulation. Several reports discuss the arguably greater importance of infection resolution, neocollateral circulation and/or contralateral sinus patency.Reference Novoa, Podvinec, Angst and Gürtler3,Reference Ganeshan, Narlawar, McCann, Jones and Curtis9,Reference Vieira, Luis, Monteiro, Temudo, Campos and Quintas28,Reference Au, Adam and Michaelides37–Reference Jackson, Porcher, Zapton and Losek40 Yet, similarly, this has not been statistically demonstrated.

There is evidence to support the safe and effective use of anticoagulation in adult cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.Reference Coutinho, de Bruijn, deVeber and Stam38,Reference de Bruijn and Stam41–Reference Stam, de Bruijn and deVeber43 Following two large trials comparing unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin with placebo, and a subsequent Cochrane review, guidelines published in the British Journal of Haematology concluded that heparin is ‘safe and potentially beneficial’ in adult cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.Reference Tait, Baglin, Watson, Laffan, Makris and Perry25,Reference Einhäupl, Stam, Bousser, De Bruijn, Ferro and Martinelli32,Reference de Bruijn and Stam41–Reference Stam, de Bruijn and deVeber43

In the absence of randomised paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis trials, it is reasonable to consider the findings of paediatric all-cause cerebral venous sinus thrombosis reports. DeVeber and colleagues’ study demonstrated 0 per cent versus 27 per cent death rates in their anticoagulated versus non-anticoagulated groups respectively.Reference deVeber, Chan, Monagle, Marzinotto, Armstrong and Massicotte44 In Kenet and colleagues’ series, there were 22 recurrent thromboses; 6 were anticoagulated and 16 were not.Reference Kenet, Kirkham, Niederstadt, Heinecke, Saunders and Stoll45 Frequencies of minor anticoagulation complications (e.g. epistaxis) amongst numerous series were insignificant (less than 10 per cent).Reference Wong, Hickman, Richards, Jassar and Wilson19,Reference Kaplan, Kraus, Puterman, Niv, Leiberman and Fliss21,Reference Koitschev, Simon, Löwenheim, Kumpf, Besch and Ernemann30,Reference de Bruijn and Stam41,Reference Shah, Jubelirer, Fish and Elden46 The British Committee for Standards in Haematology produced paediatric guidelines recommending three months of either low-molecular-weight heparin or warfarin in all secondary venous thromboembolism cases.Reference Chalmers, Ganesan, Liesner, Maroo, Nokes and Saunders47

The potential risks of serious paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis related morbidity and mortality justifies anticoagulation. It is safe in paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis cases and is significantly effective in adult cerebral venous sinus thrombosis cases.Reference Wong, Hickman, Richards, Jassar and Wilson19,Reference Einhäupl, Stam, Bousser, De Bruijn, Ferro and Martinelli32,Reference Stam, de Bruijn and deVeber43–Reference Kenet, Kirkham, Niederstadt, Heinecke, Saunders and Stoll45,Reference Barnes, Newall, Furmedge, Mackay and Monagle48–Reference Sébire, Tabarki, Saunders, Leroy, Liesner and Saint-Martin50 We recommend referral to the haematology department. All patients should be offered a three-month course of anticoagulation, specifically low-molecular-weight heparin where appropriate.

Follow up

We recognise the absence of specific literature on the subject of paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis out-patient follow up. Sinus recanalisation has been reported as an outcome measure. However, thromboses often recanalise without anticoagulation treatment.Reference Ganeshan, Narlawar, McCann, Jones and Curtis9 Furthermore, anticoagulation does not seem to influence the completeness of recanalisation.Reference Wong, Hickman, Richards, Jassar and Wilson19 No associations have been reported between recanalisation and favourable outcomes. We therefore discourage routine interval follow-up imaging in the absence of specific clinical concerns.

Paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis related disabilities can be otological, neurological and ophthalmological, and may be delayed in onset.Reference Csákányi, Rosdy, Kollár, Móser, Kovács and Katona1–Reference Neilan, Isaacson, Kutz, Lee and Roland5 Follow up of these children should therefore be through ENT surgery, neurology and ophthalmology departments. The follow-up period should be individualised, and will depend on the duration of anticoagulation and ongoing management of disabilities.

Conclusion

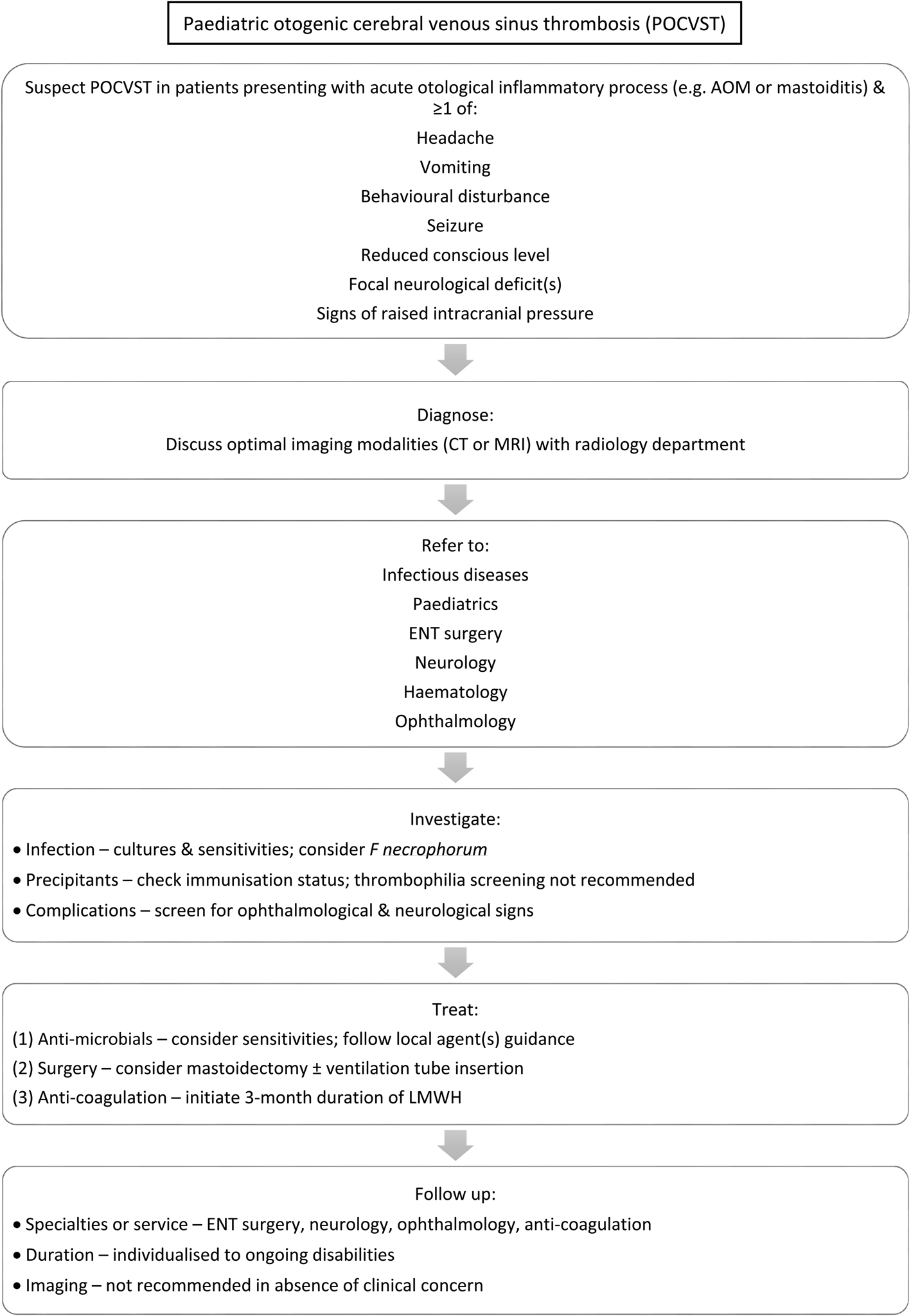

Paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is a rare, heterogeneous condition, with a lack of high-quality evidence regarding its assessment, management and follow up. Potential sequelae can be serious and occult. Treatment is often multimodal. Figure 1 summarises our recommended multidisciplinary approach to all patients with paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

Fig. 1. A flowchart presenting our recommended approach for patients with paediatric otogenic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. AOM = acute otitis media; CT = computed tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; LMWH = low-molecular-weight heparin

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the significant contributions of our multidisciplinary colleagues at the Bristol Royal Hospital for Children (University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust, UK) in analysing the evidence and collaborating on our presented guidance; namely, Denize Atan (consultant paediatric ophthalmologist), Steve Broomfield (consultant ENT surgeon), Philip Clamp (consultant ENT surgeon), David Grier (consultant paediatric radiologist), Andrew Mallick (consultant paediatric neurologist), Oliver Tunstall (consultant paediatric haematologist), Stefania Vergnano (paediatric infectious diseases consultant), Cathy Williams (consultant paediatric ophthalmologist) and Fionnan Williams (consultant paediatric radiologist).

Competing interests

None declared