Introduction

Craniopharyngiomas are uncommon, benign tumours which constitute 5 per cent of all intracranial neoplasms.Reference Bunin, Surawitz, Witman, Preston-Martin, Davis and Bruner1 Two variants have been documented: an adamantinomatous type, which commonly presents in childhood, and a papillary type, which occurs in adulthood.Reference Sorva, Jaaskinen and Heiskanen2 Craniopharyngiomas are thought to arise from Rathke's pouch epithelium, and are confined mainly to the sellar and suprasellar regions.

Although rare cases of infrasellar lesions have been reported, most of these cases had some sellar component. Truly infrasellar craniopharyngiomas with no sellar involvement are extremely rare.

We report an entirely infrasellar craniopharyngioma of adamantinomatous type in a 46-year-old woman; this tumour was unusual in both its location and the age of patient presentation.

Case report

A 46-year-old woman presented with a six-month history of predominantly left-sided nasal obstruction and congestion, pressure headaches and epistaxis. Initial treatment with antibiotics had led to some improvement in these symptoms; however, her nasal obstruction had persisted.

Rhinological examination revealed a left-sided, polypoidal lesion lying medial to the left middle turbinate. An urgent examination under anaesthesia was organised and biopsies taken.

Radiology

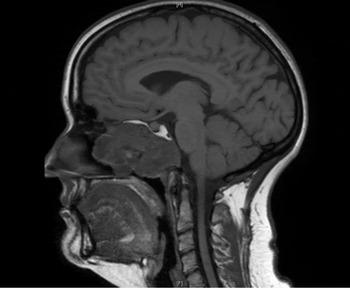

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a well defined, heterogeneous, infrasellar mass centred in the midline, which involved the clivus and expanded anteriorly into the sphenoid sinus and nasopharynx (Figure 1). There was bony erosion posterolaterally, and the mass abutted the internal carotid arteries bilaterally in the region of the foramina lacerum. Anteriorly, the mass extended into the left nasal cavity.

Fig. 1 (a) T1-weighted and (b) post-contrast, axial magnetic resonance image scans showing a heterogeneous, well enhanced, soft tissue, midline mass extending anteriorly into the nasopharynx and predominately affecting the left side. A = Anterior; P = Posterior

Fig. 2 Coronal, T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showing bilateral involvement of the internal carotid arteries. H = Head; F = Feet

Histology

Histological examination of biopsy tissue showed an epithelial tumour with a variable histological pattern. There were adamantinomatous areas resembling ameloblastoma (a benign jaw neoplasm) and other areas of squamous differentiation with keratinisation. These appearances were considered characteristic of craniopharyngioma. There was evidence of tumour erosion into bone.

The subsequent resection specimen was examined and the biopsy diagnosis confirmed.

Management

Craniofacial resection was performed via a midfacial degloving approach. Much of the bone of the sphenoid and clivus was involved and was consequently drilled away. Despite the tumour abutting 270° around both internal carotids, macroscopic clearance was achieved.

The patient underwent post-operative intensity-modulated radiotherapy.

A post-operative CT scan confirmed complete excision of the tumour.

The patient had an uncomplicated post-operative recovery, and was disease-free one year post-operatively.

Discussion

Craniopharyngiomas are benign but locally aggressive tumours. Ninety per cent of these lesions occur in the sellar or suprasellar region,Reference Carmel, Antunes and Chang3 but rare cases of infrasellar craniopharyngioma have been documented. ErdheimReference Erdheim4 postulated that craniopharyngiomas develop from squamous remnants of an incompletely involuted craniopharyngeal duct representing the route taken by Rathke's pouch from the pharynx to the floor of the third ventricle. Lesions can arise at any point along this embryological path, explaining their occurrence in extracranial sites. Cases of the paediatric subtype of adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma have been reported in the nasopharynx,Reference Lewin, Ruffolo and Saraceno5 sphenoid boneReference Cooper and Ransohoff6 and pineal gland.Reference Solarski, Panke and Panke7 However, our case represents the first report of adamantinomatous infrasellar craniopharyngioma in a woman in her fifth decade.

Fig. 3 Sagittal, T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showing a midline mass expanding anteriorly into the nasopharynx and affecting the clivus posteriorly. H = Head; F = Feet

The clinical presentation of these lesions is related to the localisation and size of the mass and to compression of local structures. Patients with suprasellar lesions commonly present with visual or endocrine disorders. In contrast, infrasellar craniopharyngiomas present with symptoms of epistaxis and nasal obstruction,Reference Byrne and Sessions8 as was the case in our patient.

Although craniopharyngiomas are regarded as a World Health Organization grade one tumour, they do exhibit an unpredictable natural history. Rare cases have been reported in which this tumour was locally aggressive, recurred multiple times, and/or transformed into carcinoma.Reference Rodriguez, Scheithauer, Tsunoda, Kovacs, Vidal and Piepgras9

As a result, the treatment of choice is complete surgical excision, with the exact surgical method determined by the anatomical location of the tumour. A lateral rhinotomy or transpalatal approach may be the method of choice for tumours confined to the nasopharynx, and endoscopic access should be used for tumours confined to the ethmoid sinus.Reference Jiang, Wu, Jan and Hsu10 The risk of local recurrence can be as high as 50 per cent if excision is incomplete.Reference Weiner, Wisoff, Rosenberg, Kupersmith, Cohen and Zagzag11 In certain patients, complete excision would entail an unacceptable risk of morbidity or mortality; in such situations, adjuvant radiotherapy is recommended since this has been shown to increase survival.Reference Eldevik, Blaivas, Gabrielsen, Hald and Chandler12, Reference Manaka, Teramoto and Takakura13

• We report an entirely infrasellar craniopharyngioma of adamantinomatous type in a 46-year-old woman; this case was unusual in both tumour location and age of presentation

• Although benign, craniopharyngiomas are locally aggressive, with a five-year survival rate which reduces with age

• These tumours should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a unilateral nasal polyp

• Complete surgical excision is recommended; if this cannot be achieved, adjuvant radiotherapy should be considered

In our patient, we chose to remove the tumour piecemeal via a midfacial degloving approach. This technique enabled complete visualisation and macroscopic excision of the tumour; furthermore, aesthetically superior results were possible due to the sublabial incision used. Although radical surgery was conducted in this case, both carotids were extensively involved and post-operative radiotherapy was thus required.

The reported overall five-year survival rate for craniopharyngioma is 80 per cent, but this is negatively affected by age: the five-year survival is 99 per cent for patients younger than 20 years, 79 per cent for those aged 20–64 years and 37 per cent for those older than 65 years. The reported overall 10-year disease-free survival rate is between 60 and 96 per cent.Reference Hetelekidis, Barnes and Tao14 Interestingly, this statistic is based purely on suprasellar craniopharyngiomas, as too few entirely infrasellar craniopharyngiomas have been reported. Consequently, the prognosis for patients with this latter tumour is unknown. We elected to closely follow up our patient with serial scans. At the time of writing, we were pleased to observe that she was disease-free, one year after surgery.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of nasopharyngeal craniopharyngioma in an adult female. These tumours are difficult to diagnose and treat. They should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a unilateral nasal polyp. Although technically benign, nasal craniopharyngiomas are usually locally aggressive, and therefore complete surgical excision is recommended. When this cannot be achieved, adjuvant radiotherapy should be considered.

Acknowledgement

We thank Mr C R Butler and Mr S L Gor.