Introduction

Granular myringitis is a chronic inflammatory disorder characterised by lateral squamous de-epithelialisation and granulation of the tympanic membrane in the absence of middle-ear disease.Reference Blevins and Karmody1–Reference Kunachak3 Studies estimate the prevalence to be around 1.2–1.8 per cent amongst adult otology out-patients.Reference Blevins and Karmody1, Reference El-Seifi and Fouad4

The aetiology is unclear. A loss of squamous epithelium on the lateral surface of the tympanic membrane is accepted as one of the preliminary stages of granulation development.Reference Blevins and Karmody1, Reference Stoney, Kwok and Hawke5 Gram-negative organisms are a common finding in affected ears, in particular, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Proteus mirabilis.Reference Jung, Cho, Yoo, Lim and Chae6, Reference Hwang, Chu and Liu7

Clinically, patients present with a combination of malodorous otorrhoea, intra-meatal itch and a feeling of aural fullness.Reference Blevins and Karmody1, Reference Stoney, Kwok and Hawke5 Granular myringitis does not classically produce a hearing deficit, but can lead to complications such as post-inflammatory medial canal fibrosis, canal atresia or stenosis, and inflammatory infiltration of the deep canal.Reference Ludman and Wright2, Reference Slattery and Saadat8, Reference Lavy and Fagan9 On otoscopic examination, focal, segmental, diffuse or polypoid, red granulation tissue on a thickened tympanic membrane may be visible. External auditory canal wall involvement and mucopurulent discharge may also be present.Reference Blevins and Karmody1, Reference El-Seifi and Fouad4, Reference Khalifa, Fouly, Bassiouny and Kamel10

Three main treatment modalities are mentioned in the literature: topical antibiotic with steroid drops; cauterisation of granulations; and debridement of granulomatous tissue.Reference Blevins and Karmody1, Reference Stoney, Kwok and Hawke5, Reference Khalifa, Fouly, Bassiouny and Kamel10, Reference Roland, Dohar, Lanier, Hekkenburg, Lane and Conroy11 However, there is no universal treatment which has proven effective in every case.Reference Khalifa, Fouly, Bassiouny and Kamel10

Although granular myringitis appears to respond initially to topical antibiotic therapy, this does not prevent the condition from recurring.Reference El-Seifi and Fouad4, Reference Lee12 The condition typically has a relapsing and remitting course.Reference Blevins and Karmody1 Ineffective treatment prolongs the patient's misery and may lead to the aforementioned complications – hence the need for identification of successful, evidence-based treatment guidelines.

By conducting a systematic review of the current literature, this review aimed to determine a management plan to treat and prevent recurrence of granular myringitis, which could then be integrated into clinical practice. Our report will also highlight topics lacking research of high quantitative and qualitative value, indicating areas requiring further study.

Methods

Literature search

Current literature on granular myringitis was obtained by thorough searching of evidence-based medical databases, the Cochrane database of systematic reviews, the Database of Abstracts and Reviews of Effects, the Cochrane controlled trials register, Ovid Medline, the various British Medical Journal imprint journals, individual journal websites and citation indexes, as well as hand-searching of current journals to include new publications. Unpublished literature searches were performed using ‘grey area’ search engines, and generalised internet search engines were also used to increase search sensitivity. The search terms included ‘granular myringitis’ and synonyms, ‘myringitis’ and ‘granular ear disease’. Reference lists of articles and relevant textbooks were consulted to optimise search sensitivity. The search was tested for reproducibility and updated throughout the duration of the study. The range of studies collected covered the years 1964 to 2005.

Inclusion criteria protocol

Type of study

Randomised controlled trials, controlled case studies and observational reports were included in the initial screening process. The minimal acceptable number of patients per trial was 20.

Type of patient

The review included adults with a clinical diagnosis of granular myringitis of at least three weeks' duration, based on clinical history and examination. Inclusion required reported otoscopic findings of focal, diffuse or segmental granulation of the lateral tympanic surface. A diagnosis based on clinical history alone was deemed inappropriate and unreliable, due to the possibility of misdiagnosis with cholesteatoma or chronic suppurative ear disease. Patients suffering from co-morbid middle-ear disease were excluded.

Types of intervention

Any proposed management of granular myringitis was accepted, including medical topical or oral therapy and surgical management.

Types of outcome

The primary outcome assessed was recurrence of granular myringitis. Publications were screened for potential relevance and then further assessed by the preset inclusion criteria.

The studies which remained were critically appraised to expose any methodological flaws or biases. All studies were assessed with regards to randomisation, double-blinding and loss to follow up, and evaluated using the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine grading system.13

Data were retrieved from the selected studies and checked for accuracy and consistency throughout the paper. Any apparent losses to follow up were investigated and checked. The primary outcome sought was whether the proposed intervention reduced the risk of recurrence of granular myringitis.

Results

Fifty-eight publications were identified by the initial search, 46 of which were screened as being potentially relevant. However, after assessing each publication using the preset inclusion criteria, only two studies satisfying these criteria were found. A summary of the results at each stage of the search is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1 Search method.

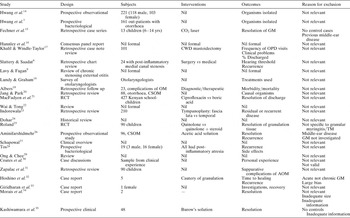

The properties of the 44 studies which did not meet the inclusion criteria are given in Table I.

Table I Characteristics of excluded studies

Yrs = years; GM = granular myringitis; CWD = canal wall down; OPD = out-patients department; OM = otitis media; CSOM = chronic suppurative otitis media; RCT = randomised, controlled trial; TM = tympanic membrane; AOM = acute otitis media

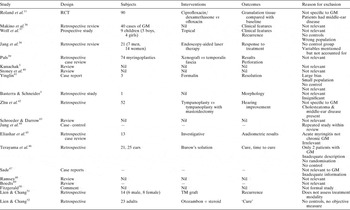

The properties of the two studies which met the inclusion criteria are tabulated in Table II.

Table II Characteristics of included studies

* Standard therapy. Yr = years; M:F = male/female ratio; GM = granular myringitis; 2° = secondary; min = minimum; mth = months; max = maximum; 3° = tertiary

Quality assessment

The evidential value of each study was assessed according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine guidelines.13 The study by Jung et al. Reference Jung, Cho, Yoo, Lim and Chae6 was considered to contain grade IIb evidence and the study by El-Seifi and FouadReference El-Seifi and Fouad4 to contain grade IIc evidence.

These two studies were then appraised according to their methodological quality, taking into account: randomisation of subjects, accounting for all subjects, blinding of patients, blinding of treating physicians and additional sources of bias. These aspects are discussed for each study, below.

Description of studies

Jung et al. Reference Jung, Cho, Yoo, Lim and Chae6

This study selected 30 patients with diagnosed granular myringitis (23 women, 7 men), over a seven-year period, for non-blinded assignment into two groups of 15. The control group received conventional treatment with ofloxacin ear drops two to four times daily. The intervention group received aural toilet with vinegar solution once or twice daily. All patients were treated until otoscopy showed a dry tympanic membrane with no granulations. Patients were followed up for six months, and the outcomes measured included recurrence rate, recovery time, therapeutic efficiency and tolerance of therapy.

El-Seifi and Fouad.Reference El-Seifi and Fouad4

This study retrospectively reviewed 94 patients (49 men, 45 women) presenting with granular myringitis over a period of 28 years. All 94 patients were assessed with regards to possible aetiology and symptoms, but only 74 were included in the treatment case series due to inclusion criteria conditions. Twenty-six patients were treated conservatively, with the centre's protocol of thrice daily irrigation with 1.5 per cent acetic acid, followed by drying of the ear and application of either gentamicin or neomycin with dexamethasone steroid drops. Patients were seen every few days to clean the discharge and debris and to apply a steroid anti-fungal cream. If granular myringitis persisted, the granulations were cauterised with 50 per cent trichloracetic acid and an oral quinolone given. Surgical management entailed excision of all granular material from the tympanic membrane and the meatal wall. The area was grafted using underlay cartilage from the tragus. Routine follow up comprised monthly review for six months and then annual review as required. The follow-up time ranged from six months to 12 years, depending on recurrence. The primary outcome measured was the recurrence rate.

Methodological quality

Jung et al. Reference Jung, Cho, Yoo, Lim and Chae6

Although this study was a case-controlled trial, there was no mention of randomisation of patients. It was therefore considered to be non-randomised, introducing a possible source of bias. It was also a relatively small study, with only 30 subjects overall.

The diagnostic inclusion criteria were very precise, thus ensuring the correct diagnosis in all subjects. All subjects had malodorous otorrhoea, granulation tissue on the tympanic membrane under microscopic examination and a type A tympanogram. To ensure correct diagnosis, patients with chronic otitis media, tympanic membrane perforations, type B or C tympanograms, or the presence of middle-ear disease on imaging were excluded.

All subjects who started the trial were accounted for in the results section and were followed up for six months; however, there was no blinding of patients or physicians.

Another potential source of bias arose from the drainage and drying of the external ear canal with a hairdryer for one minute after instillation of the treatment in the intervention group, whereas this treatment was not mentioned in the control group. This therefore added another variable which could have introduced bias to the results.

The researchers in this study had actively attempted to exclude bias with regards to the concentration of vinegar solution used: 10 ml of initial solution of pH 2.25 ± 0.02 was added to 30 ml of water, with a resultant solution pH of 2.43 ± 0.02.

El-Seifi and Fouad.Reference El-Seifi and Fouad4

This non-randomised, retrospective study reported follow up for all patients, but was obviously not blinded due to its retrospective nature. The control group of 26 subjects was also outweighed by the intervention group of 48 subjects; however, the same outcome – recurrence rate – was measured for all subjects.

This study also used strict diagnostic inclusion criteria. Patients were assessed according to clinical history and examination, otoscopic examination, tympanic membrane microscopy and pure tone audiometry, in order to eliminate concomitant middle-ear disease (including cholesteatoma and chronic suppurative otitis media).

Analysis of study results

After collection and analysis of results, it was considered inappropriate to conduct a formal meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity seen across both studies and the risk of producing a spurious result. However, the results of both studies were tabulated and analysed in order to determine absolute indicators of optimal treatment.

Table III Results: jung et al. 6

Table IV Results: el-seifi & fouad4

Jung et al. Reference Jung, Cho, Yoo, Lim and Chae6

The primary outcome of this study is shown in Table III. As these results show no recurrence in the intervention group, it is not possible to calculate an odds ratio or risk ratio. In this case, the results have been analysed to produce a risk difference and number needed to treat, to prevent introduction of more bias. According to this study, there was an 80 per cent increased chance of recovery without recurrence of granular myringitis following treatment with dilute topical vinegar solution, compared with ofloxacin ear drops. The number of patients requiring treatment in order for one patient to benefit was calculated as 1.25.

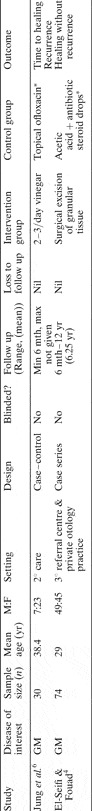

Regarding secondary outcomes, Jung et al. also published the time to resolution of symptoms and of granulation tissue. These results are shown graphically in Figure 2. The instillation of dilute vinegar solution into the external auditory meatus appeared to reduce the time to resolution of symptoms, compared with conventional antibiotic treatment. By the end of week one in the intervention group, 12 patients (80 per cent) had achieved resolution of symptoms, compared with two patients (13 per cent) in the control group. Another important secondary outcome explored by this study was the experience of side effects in the intervention group. Two patients experienced mild ear discomfort and one patient had an episode of mild dizziness. No information is given on the side effects of treatment with ofloxacin and, although these have been described elsewhere,Reference Mehta53 other studies do not give a comparative result in this population with granular myringitis.

Fig. 2 Time to resolution of granular myringitis, Jung et al. 6

El-Seifi and Fouad.Reference El-Seifi and Fouad4

Table IV shows the primary outcomes of this study. As these results contained a zero, they were analysed as risk difference and number needed to treat. Patients in this study had a 96 per cent increased chance of recovery from granular myringitis without recurrence after surgical excision of all granular tissue, compared with conservative topical antibiotic and steroid drop therapy. The number of patients requiring treatment in order for one patient to benefit was calculated as 1.04.

Discussion

Jung et al. demonstrated a 96 per cent absolute reduction in recurrence of granular myringitis following treatment with a dilute vinegar solution, compared with ofloxacin ear drops.

Several studies have acknowledged high pH in the external auditory meatus as a possible aetiological factor in the precipitation and maintenance of granular myringitis. This supports Jung and colleagues' study of vinegar treatment. The use of daily irrigation of the external auditory canal with vinegar and water has been suggested by Lee.Reference Lee12 There are no published case reports which confirm the results of this study. However, a retrospective report describing the positive effect of the acidic Burow's solution (aluminium acetate) in two patients with granular myringitis gives a little support to the theory of low pH as an aid in preventing recurrence.Reference Terayama, Takizawa, Gotouda, Sutou and Kashiwamura46

El-Seifi and Fouad demonstrated that surgical excision of granulation tissue reduced recurrence of granular myringitis by 80 per cent, compared with conventional antibiotic therapy. A retrospective, non-controlled case study published in the latter stages of the present review supports the hypothesis posed by El-Seifi and Fouad, i.e. that complete excision of all granulation tissue may have a place in the long term management of granular myringitis. This study investigated endoscopy-aided laser ablation of granulations, which led to resolution in 18 of 21 cases after a single treatment.Reference Jang, Kim, Cho and Wang38 However, treatment of the control group with acetic acid may explain why the majority of subjects did not respond, as acetic acid is a known irritant of inflammatory tissue and may itself cause aural discomfort.

The evidential and methodological value of each study must be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. Although both studies showed a greater than 80 per cent reduced risk of recurrence in the intervention group, it must be noted that neither study was randomised or blinded, making it difficult to assess the clinical relevance of the results. Both studies were also of modest evidential value.

With regards to ethical considerations and clinical decision-making, the surgical technique described by El-Seifi and FouadReference El-Seifi and Fouad4 may reduce granular myringitis recurrence, but the general risks associated with surgery and anaesthesia must be taken into consideration before applying the results in practice. The use of endoscopy-aided laser therapy to debride granulations may be a useful development in the future; this technique ablates granulations without the need for anaesthesia, and case reports have shown it to be effective in a number of patients.Reference Fechner, Cunningham and Eavey15, Reference Zhu, Zhang, Yu, Zhang and Yu38

Although granular myringitis is a troublesome condition, the complications of surgery may be far worse than the symptoms of the disease. Therefore, surgical debridement would be of optimal use in intractable, symptomatic patients.

Both studiesReference El-Seifi and Fouad4, Reference Jung, Cho, Yoo, Lim and Chae6 showed that their respective techniques were superior to topical antibiotic therapy in treating and preventing recurrence of granular myringitis. Therefore, the main clinical implication of this review is that alternative therapies should be considered when granular myringitis is encountered.

On another topic, other studies have made clear that inadequate clinical assessment often leads to a misdiagnosis of granular myringitis as chronic suppurative otitis media.Reference Khalifa, Fouly, Bassiouny and Kamel10 The present review, and the studies it included, each used strict inclusion criteria for the identification of patients with granular myringitis; these criteria represent potentially useful diagnostic tools in clinical practice.

Conclusions

From this limited review, we draw the following conclusions.

Firstly, in the management of granular myringitis, conventional topical antibiotic and steroid drops appear to be less efficacious and more likely to lead to recurrence of symptoms, compared with other proposed treatment modalities.

Secondly, there is at present insufficient high quality evidence to support any particular management plan or treatment protocol for patients suffering from granular myringitis. However, treatment with dilute vinegar solution presents a logical, unharmful alternative to conventional antibiotic drops.

Thirdly, further research of high value (i.e. randomised controlled trials) is needed to further assess and identify management strategies which both resolve granular myringitis and prevent its recurrence (e.g. surgical debridement, endoscopy-aided laser therapy, cautery and topical application of low pH solutions).

Fourthly, a standard protocol for diagnosis of granular myringitis is required in order to avoid misdiagnosis and to prevent inappropriate management.