Introduction

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours are soft tissue sarcomas derived from the mesenchymal cells of the neural crest. These tumours are rare in the head and neck region, and most commonly present in the seventh decade.

We report a recent case in a 38-year-old woman and we present a review of the literature, in order to highlight this condition as a potential diagnosis.

Case report

A 38-year-old Caucasian woman, with no past medical history of note, presented with a six-month history of swelling associated with numbness around her left nasolabial fold, with no other symptoms.

Examination revealed a 1 cm diameter, smooth, non-tender lump attached to the skin. The nasal cavity was normal and no cervical lymphadenopathy was present.

A fine needle aspiration biopsy was performed, showing predominately pleomorphic spindle cells.

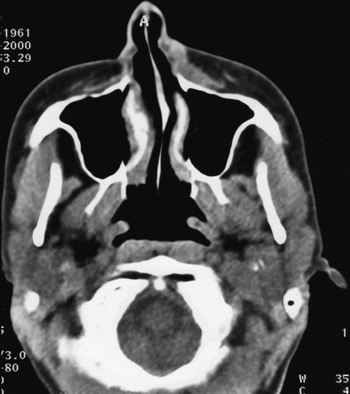

Computed tomograpy (CT) scanning showed a soft tissue density in the left nasolabial region, with no evidence of bone destruction or encroachment on the nasal cavity (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 Axial computed tomography scan showing a well defined mass visible in the subcutaneous tissues anterior to the left maxilla, extending onto the labia of the nose.

An excisional biopsy was performed via a sub-labial approach. The lesion was well demarcated, centred over the left nasal bone and closely related to the left infraorbital nerve. The majority of the mass was removed at this stage; however, proximity to the infraorbital nerve prevented total excision.

Histological examination showed features of a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour (Figure 2). This was composed of medium to large spindle cells showing marked cellular pleomorphism and mitotic activity exceeding 10 mitoses per 10 high power fields (1 high power field = 0.26 mm2), plus some atypical mitoses. No fibrous capsule or hyaline blood vessels were present. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated S100 positivity in greater than 75 per cent of cells. A significant minority also expressed epithelial membrane antigen.

Fig. 2 (a) Photomicrograph, H&E staining, showing spindle cell proliferation with a moderate degree of cytological pleomorphism. Three mitotic figures are visible (arrows) (×200). (b) Photomicrograph, immunoperoxidase staining (avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method); some of the spindle cells show nuclear and cytoplasmic expression of S100 protein (arrows) (×200).

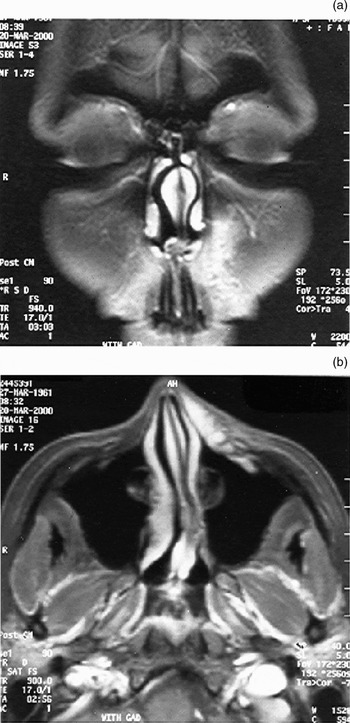

Comprehensive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning was performed before planned re-excision. This demonstrated tumour involving the left side of the nose and extending inferiorly almost to the vermillion border of the lip. The infraorbital nerve was involved for at least 1 cm, and the tumour was in contact with the alveolar margin. No invasion of the maxillary antrum or eyelid was demonstrated (Figure 3).

Fig. 3 (a) Coronal, T1-weighted, fat-suppressed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan after gadolinium enhancement. The tumour is diffuse and clearly seen spreading towards the vermillion border. (b) Axial, T1-weighted, fat-suppressed MRI scan after gadolinium enhancement. Note bright enhancement of the normal mucosa of the nose. The tumour enhances, and its permeating nature in the subcutaneous tissue can be clearly appreciated. There is pathological enhancement of the infraorbital nerve, indicating neural invasion (confirmed at surgery).

A wide enbloc resection was performed involving the left lateral nasal wall, front face of the maxilla, orbital floor and medial wall of the orbit to include the infraorbital and anterior ethmoidal nerves, along with the overlying skin. The left inferior turbinate and ethmoid sinuses were also resected. Clear margins were confirmed by frozen section histology.

Reconstruction of the front of the maxilla, orbital floor and lateral nasal wall was performed using split temporal calvarial bone and a free radial forearm flap.

Histological analysis of the resected specimen demonstrated a lobulated spindle cell tumour, well circumscribed in parts but with some irregular, infiltrating fascicles extending into the dermis and skeletal muscle. There was extension through the maxillary bone into the submucosa of the maxillary sinus in one area. The infraorbital nerve was involved, but no tumour was identified in the anterior ethmoidal nerve. Margin clearances were all greater than 5 mm. The histological appearance of the tumour was identical to the original biopsy specimen.

The patient's post-operative recovery was uneventful, and a course of radiotherapy to the site was performed. A five-year post-operative MRI scan revealed no evidence of tumour recurrence. At the time of writing, the patient remained fit and well.

Discussion

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours account for 4–10 per cent of all soft tissue sarcomas, affecting approximately 0.001 per cent of the population.Reference Enzinger and Weiss1, Reference Ducatman, Scheithauer, Piepgras, Reiman and Ilstrup2 The general consensus is that men and women are equally affected, although a female preponderance has been noted.Reference Cashen, Parisien, Raskin, Hornicek, Gebhardt and Mankin3 No racial association has been documented, and the majority of studies show a peak incidence in the seventh decade.Reference Ducatman, Scheithauer, Piepgras, Reiman and Ilstrup2–Reference D'Agostino, Soule and Miller4

The aetiology of spontaneous malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour remains unclear. The majority arise de novo in normal peripheral nerves; however, transformation from a pre-existing neurofibroma is known. Patients with neurofibromatosis type one are at increased risk, with a cumulative lifetime risk of up to 10 per cent.Reference Cashen, Parisien, Raskin, Hornicek, Gebhardt and Mankin3 The incidence of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour in individuals with neurofibromatosis type one peaks around the third decade.Reference Wong, Hirose, Scheithauer, Schild and Gunderson5 Patients with neurofibromatosis type one account for about 50–60 per cent of cases seen.Reference Tucker, Wolkenstein, Revuz, Zeller and Friedman6 These tumours are 18 times more likely to arise in individuals with neurofibromatosis type one and internal plexiform neurofibromas.Reference Tucker, Wolkenstein, Revuz, Zeller and Friedman6

Approximately 10 per cent of patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours have had prior radiation exposure and can be considered to have radiation-induced tumours, which develop on average 15 years after the initial treatments.Reference Cashen, Parisien, Raskin, Hornicek, Gebhardt and Mankin3, Reference Wong, Hirose, Scheithauer, Schild and Gunderson5, Reference Baehring, Betensky and Batchelor7, Reference Kourea, Bilsky, Leung, Lewis and Woodruff8 Both patients with and without neurofibromatosis type one have been observed to develop malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours after irradiation therapy for head and neck tumours, Wilms' tumour, Hodgkin disease, and testicular malignancy.Reference Baehring, Betensky and Batchelor7, Reference Loree, North, Werness, Nangia, Mullins and Hicks9, Reference Amin, Saifuddin, Flanagan, Patterson and Lehovsky10

Gross inspection of a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour reveals a fusiform, fleshy, white mass with areas of degeneration and secondary haemorrhage. The nerve proximal and distal to the tumour may be thickened. Histologically, the majority of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours are composed of spindle cells showing variable degrees of pleomorphism. The cells are typically arranged in a storiform or interweaving fascicular pattern.Reference Bailet, Abemayor, Andrews, Rowland, Fu and Dawson11, Reference Angelov, Davis, O'Sullivan, Bell and Guha12 Differentiation from other soft tissue sarcomas may be difficult; however, a soft tissue sarcoma is thought to be of neurogenic origin if it fulfills any of the following characteristics: macro- or microscopic association with a peripheral nerve; malignant transformation of a pre-existing neurofibroma; or immunohistochemical or ultrastructural features consistent with peripheral nerve origin.Reference Angelov, Davis, O'Sullivan, Bell and Guha12

Immunohistochemistry, using a panel of antibodies, reveals that the majority of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours express S100 protein but do not express human melanoma black 45 (HMB-45 is the monoclonal antibody name.), melan-A, cytokeratin, smooth muscle actin or desmin. Some tumours, as in the presented case, express epithelial membrane antigen. Although this may be indicative of a degree of perineural differentiation, it is not, in the absence of ultrastructural evidence, diagnostic.Reference Angelov, Davis, O'Sullivan, Bell and Guha12

Prior to the advent of CT and MRI, imaging of nerve lesions depended on plain radiographs, surveying for secondary bone changes. With the introduction of MRI and CT imaging, soft tissue and nerves became visible. Imaging with these modalities and angiography can help differentiate malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours from aneurysmal formations, vascular tumours, lipomata, osteosarcomata and metastases. Computed tomography scans prove useful in estimating the distribution of the disease and the extent of bone destruction, while bone marrow infiltration is best visualised using MRI.

Positron emission tomography (PET) with the glucose analogue fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is a potentially useful, noninvasive method for detecting malignant changes. This form of imaging is proving to be increasingly popular in cases of plexiform neurofibromas. A recent study by Williams et al. Reference Williams, Coumans, Bredella, Miriam, Torriani and Hornicek13 reported the sensitivity and specificity of PET-based investigations to be in the region of 95 per cent when fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) was combined with 11C methionine.

Patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours have a poor prognosis, which appears to be worse in those with neurofibromatosis type one.Reference Cashen, Parisien, Raskin, Hornicek, Gebhardt and Mankin3, Reference Ferner and Gutmann14 The worst outcomes are related to incomplete tumour resection,Reference Cashen, Parisien, Raskin, Hornicek, Gebhardt and Mankin3, Reference Wong, Hirose, Scheithauer, Schild and Gunderson5 as malignant cells spread extensively within the fascial planes, resulting in high recurrence rates and ultimate systemic spread.Reference Cashen, Parisien, Raskin, Hornicek, Gebhardt and Mankin3, Reference Angelov, Davis, O'Sullivan, Bell and Guha12, Reference Hirose, Scheithauer and Sano15 Adverse prognostic factors include a size of 5 cm or larger, high-grade tumour, advanced histological characteristics, and surgical margin with tumour invasion.Reference Angelov, Davis, O'Sullivan, Bell and Guha12 The five-year survival rates in large series has been reported to range from 16 to 52 per cent.Reference Cashen, Parisien, Raskin, Hornicek, Gebhardt and Mankin3, Reference Wong, Hirose, Scheithauer, Schild and Gunderson5, Reference Kourea, Bilsky, Leung, Lewis and Woodruff8, Reference Simon and Enneking16 The reported five-year survival rate for patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours without neurofibromatosis type one is as high as 50 per cent, but drops to as low as 10 per cent in patients with neurofibromatosis type one.Reference Ferner and Gutmann14

Wide surgical excision is the best treatment for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour.Reference Cashen, Parisien, Raskin, Hornicek, Gebhardt and Mankin3, Reference Singer, Corson, Gonin, Labow and Eberlein17 Primary radiotherapy has been shown to give poor results,Reference Wong, Hirose, Scheithauer, Schild and Gunderson5 although adjuvant radiotherapy may improve local control.Reference Wong, Hirose, Scheithauer, Schild and Gunderson5, Reference Bailet, Abemayor, Andrews, Rowland, Fu and Dawson11, Reference Singer, Corson, Gonin, Labow and Eberlein17 Negative surgical margin status is the most significant prognostic factor in achieving local control, and subsequently improving overall survival.Reference Wong, Hirose, Scheithauer, Schild and Gunderson5

• Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours are rare

• This paper describes a case of such a tumour presenting in the infraorbital region

• Presentation is often insidious

• Early diagnosis is crucial

• Surgical resection and post-operative radiotherapy are the mainstays of treatment

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours affect the head and neck in only 8–15 per cent of cases.Reference Bailet, Abemayor, Andrews, Rowland, Fu and Dawson11 To date, approximately 100 cases of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour affecting the head and neck have been reported.Reference Simon and Enneking16, Reference Martinez-Devesa, Mitchell, Scott and Moffat18 The usual presentation is of a painlessly enlarging mass with or without numbness or sensory changes in the distribution of the affected nerve. The most commonly involved sites include the brachial plexus, sympathetic chain and trigeminal nerve. Most cases affecting the head and neck are located in the parotid gland.Reference Martinez-Devesa, Mitchell, Scott and Moffat18, Reference Hutcherson, Jenkins, Canalis, Handler and Eichel19 Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours account for only 2 per cent of malignant sinonasal tumours.Reference Hellquist and Lundgren20 Regional lymph node metastasis is rare, although well recognised, especially with the epithelioid variant;Reference Hutcherson, Jenkins, Canalis, Handler and Eichel19 even so, prophylactic treatment of nodes is not advocated.Reference Greager, Richard, Campana and Das Gupta21 Distal metastasis tends to occur haematogenously to the lungs or bone in approximately 33 per cent of cases.Reference Bailet, Abemayor, Andrews, Rowland, Fu and Dawson11 The overall survival rate of patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours of the head and neck is between 15 and 29 per cent.Reference Bailet, Abemayor, Andrews, Rowland, Fu and Dawson11, Reference Greager, Richard, Campana and Das Gupta21 Wide local excision with pathologically negative margins is the mainstay of treatment.Reference Cashen, Parisien, Raskin, Hornicek, Gebhardt and Mankin3, Reference Williams, Coumans, Bredella, Miriam, Torriani and Hornicek13, Reference Colreavy, Lacy, Hughes, Bouchier-Hayes and Brennan22 Inadequate wide excision, particularly in the case of excisional biopsies, generally has a high rate of local recurrence.Reference Colreavy, Lacy, Hughes, Bouchier-Hayes and Brennan22

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour affecting the distal or peripheral branches of the cranial nerves is recognisedReference Martinez-Devesa, Mitchell, Scott and Moffat18, Reference Hutcherson, Jenkins, Canalis, Handler and Eichel19 but appears less common than involvement of the main nerve trunks. Maroun et al. Reference Maroun, Sadler, Mangan, Mathieson, Jacob and Kwan23 reviewed all six reported cases of malignant schwannoma involving the trigeminal nerve. One of the main nerve branches was involved in all cases, allowing complete resection in only two cases. Hellquist and LundgrenReference Hellquist and Lundgren20 reported five cases of sinonasal neurogenic sarcomas, presumed to have originated from the trigeminal nerve. All had bone destruction at presentation.

Initial presentation involving a distal superficial, peripheral branch, as in the presented case, should allow complete resection and hence improved survival. Results for similarly located tumours are presented in Table I.

Table I Reported cases of superficially located malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour of the trigeminal nerve

* No further information available. Y = years; R = right; L = left; DOD = died of disease; mth = months; MPNST = malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of obtaining imaging and histological diagnosis in patients presenting with sensory changes associated with a mass. An accurate, early diagnosis is important due to the locally aggressive nature of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. Currently accepted treatment involves surgical resection and post-operative radiotherapy. Magnetic resonance image scanning is essential to determine the extent of soft tissue involvement and to enable surgical planning.