Introduction

Up to 70 per cent of temporal bone fractures are secondary to high-energy blunt head trauma such as road traffic accidents, assault and falls.Reference Hasso and Ledington1–Reference Ishman and Friedland5 Associated intracranial injuries often require early management or intervention.Reference Zayas, Feliciano, Hadley, Gomez and Vidal6

Temporal bone fractures are currently classified according to otic capsule involvement. Non-otic capsule sparing fractures course through labyrinthine structures (cochlea, vestibule and semi-circular canals), and are associated with complications such as facial nerve palsy, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak and profound sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL).Reference Cannon and Jahrsdoerfer7,Reference Little and Kesser8 Otic capsule sparing fractures tend to affect the tegmen, middle ear and external auditory canal. Approximately 95 per cent of all temporal bone fractures are otic capsule sparing fractures.9

This study aimed to review the management of temporal bone fractures at a major trauma centre in London and introduce an evidence-based protocol.

Materials and methods

A retrospective review of computed tomography (CT) imaging reports of a series of head trauma cases was undertaken over a six-year period from January 2012 to July 2018. The neuroradiologist on duty reported on all images.

The recorded data fields included: mode of trauma (blunt or penetrating), patient age (aged over or under 18 years), associated intracranial injury, mortality, fracture pattern (otic capsule sparing or non-otic capsule sparing), ENT symptoms and intervention. Imaging reports that were not accessible from the skull base trauma database were excluded from the study. Information relating to clinical symptoms and intervention was obtained from electronic patient records (via Cerner™ PowerChart software).

Data were handled using Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet software, and analysed with SPSS® statistical software, version 23 for Mac.

Results

Reports for 815 temporal bone fractures (704 patients) were derived from a series of 1228 skull base fractures. Of the 704 patients, 613 had associated intracranial injury (87 per cent) and 124 patients died (17.6 per cent). Eighty-six CT head scans did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded from the study. Electronic records were available for only 165 patients; detailed analysis was performed on the reports of these patients (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Flowchart showing a breakdown of the study data. *Pure tone audiometry data available for only 81 of 165 patients, accounting for the variability in total numbers seen throughout the results section. CT = computed tomography

Overview of results

Of the 165 patients within the series, 150 had otic capsule sparing fractures and 15 had non-otic capsule sparing fractures. Bilateral fractures occurred in 22 patients. A greater proportion of patients with non-otic capsule sparing fractures underwent surgery than patients with otic capsule sparing fractures, but this difference was not significant (2 out of 7 vs 7 out of 63; p = 0.219, Fisher's exact test). See Tables 1 and 2 for a full breakdown of data.

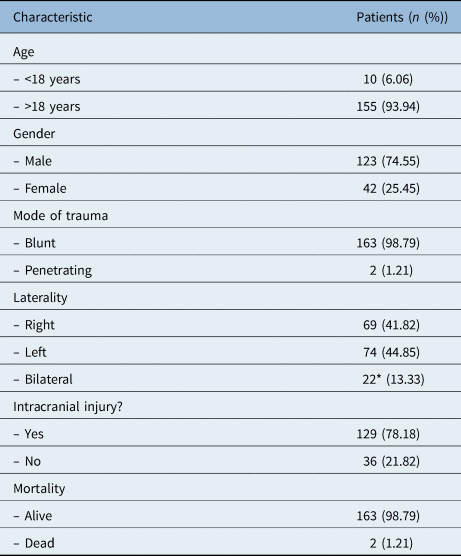

Table 1. Patient demographics

*This figure reflects the number of patients with bilateral fractures; the number of bilateral fractures was 44.

Table 2. Data fields classified by fracture pattern

*Chi-square test for trend. PTA = pure tone audiometry; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; BPPV = benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

Paediatric population results

There were 10 paediatric patients in the series. There was no significant difference in fracture pattern (otic capsule sparing vs non-otic capsule sparing) between children and adults (9 out of 10 vs 141 out of 155; p = 0.918, Fisher's exact test). Electronic clinical case records were available for four patients. Three patients had undergone pure tone audiometry; one patient had mild hearing loss, one had severe hearing loss and one had a dead ear. There were no other associated symptoms and no patients required surgery.

Hearing loss results

Pure tone audiometry showed that 31 patients had no trauma-related hearing loss, 24 had conductive hearing loss, 20 had SNHL and 6 had a mixed pattern (Table 2). Fifty-seven patients seen in the ENT clinic were documented as having hearing loss, but did not have pure tone audiometry data available. These patients were recorded as having hearing loss not otherwise specified, and their data were not included in further analyses.

A significantly greater proportion of patients with non-otic capsule sparing fractures had SNHL than patients with otic capsule sparing fractures (8 out of 9 vs 18 out of 41; p < 0.001, Fisher's exact test). The odds of SNHL in patients with non-otic capsule sparing fractures were nearly seven times those in patients with otic capsule sparing fractures (odds ratio = 6.75, 95 per cent confidence interval = 1.06–43.04). Of the 26 patients with SNHL (including those with a mixed pattern), hearing loss was mild in 1 patient (3.8 per cent), moderate in 7 patients (26.9 per cent), severe in 5 patients (19.2 per cent), and profound or with a dead ear in 13 patients (50 per cent). Non-otic capsule sparing fractures were associated with an increased severity of hearing loss (p = 0.022, chi-square test for significance trend).

There was no significant association between conductive hearing loss and fracture pattern; there was hearing loss in 1 out of 13 (7.7 per cent) of non-otic capsule sparing fracture cases, compared with 29 out of 125 (23.2 per cent) of otic capsule sparing fracture cases (p = 0.3, Fisher's exact test).

Data on ossicular continuity were taken from CT reports and were available for 104 patients. There was no significant relationship between ossicular discontinuity and fracture pattern; there was ossicular discontinuity in 28 out of 94 (29.8 per cent) of otic capsule sparing fracture cases, compared to 3 out of 10 (30 per cent) of non-otic capsule sparing fracture cases (p = 0.621, Fisher's exact test).

Cerebrospinal fluid leak results

A total of 13 patients had a CSF leak. A greater proportion of patients with non-otic capsule sparing fractures had a CSF leak than patients with otic capsule sparing fractures, but the difference was not significant (3 out of 10 vs 10 out of 123; p = 0.59, Fisher's exact test). Patients with CSF leaks were no more likely to be given antibiotics than those without (2 out of 13 vs 3 out of 120; p = 0.075, Fisher's exact test). One patient developed meningitis secondary to an anterior skull base fracture, but it is unclear whether surgical repair was required.

Facial nerve palsy results

Five patients had immediate facial nerve palsy and 20 had delayed facial nerve palsy. Patients with non-otic capsule sparing fractures were significantly more likely to have immediate facial nerve palsy than those with otic capsule sparing fractures (3 out of 10 vs 2 out of 122; p = 0.003, Fisher's exact test). Patients with facial nerve palsy were significantly more likely to be given steroids than those without (11 out of 25 vs 0 out of 107; p < 0.001, Fisher's exact test). Of the 20 patients with delayed facial nerve palsy, 10 (50 per cent) were given steroids, compared to only 1 patient with immediate facial nerve palsy. All five patients with immediate facial nerve palsy underwent surgery and information for three of these patients could be retrieved.

Other symptoms

There was no significant difference between the presence of haemotympanum between patients with otic capsule sparing and non-otic capsule sparing fractures (p = 2.85, Fisher's exact test). Seven patients were recorded as having benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), 15 had vertigo, 2 had canal stenosis, and 5 had hyposmia or anosmia. There was no significant relationship between fracture type and any associated symptom.

Discussion

This study represents the largest UK series of temporal bone fractures. Around 99 per cent of fractures were secondary to blunt trauma, and there was an associated intracranial injury in nearly 80 per cent of patients. Fracture pattern ratios (comparing otic capsule sparing and non-otic capsule sparing fractures) within our series are comparable with data reported in the largest published cohort of 820 fracture cases from the USA.Reference Brodie and Thompson4

Paediatric population

There were limited data available for subgroup analysis on the paediatric population. Published studies have reported the incidence of temporal bone fractures as 8 per cent,Reference Waissbluth, Ywakim, Al Qassabi, Torabi, Carpineta and Nguyen10 with the fractures often having a bimodal distribution, frequently occurring at 3 and 12 years.Reference McGuirt and Stool11,Reference Lee, Honrado, Har-El and Goldsmith12 There is a lower reported incidence of facial palsy in children, which is theorised to be the result of skull malleability, which also lessens the impact and reduces the likelihood of fractures.Reference Nishiike, Miyao, Gouda, Shimada, Nagai and Nakagawa13

Hearing loss

Conductive hearing loss is frequently observed in temporal bone fracture cases. It is often secondary to haemotympanum, tympanic membrane perforation or ossicular chain disruption. At our centre, all temporal bone fracture patients are followed up in the ENT emergency clinic or otology clinic.

Our data showed no significant association between conductive hearing loss or ossicular discontinuity and fracture pattern. Thirty-one patients were noted to have ossicular discontinuity on CT, with records showing that five underwent ossiculoplasty. At surgery, three were found to have incudomalleolar dislocation. This is relatively uncommon amongst documented ossicular chain abnormalities, with the commonest being incudostapedial joint dislocation, followed by incus dislocation, fracture of stapes superstructure, ossicular fixation in the attic and incudomalleolar joint separation.Reference Brodie, Flint, Haughey, Lund, Niparko, Richardson and Robbins14,Reference Hough, Paparella and Shumrick15

Our data demonstrated that a significantly greater proportion of patients with non-otic capsule sparing fractures had SNHL than patients with otic capsule sparing fractures (8 out of 9 vs 18 out of 41; p < 0.001, Fisher's exact test). The likelihood of SNHL was 7 times higher in the non-otic capsule sparing fracture group; previous studies have reported the likelihood as being up to 25 times higher in this group.Reference Little and Kesser8 Over 50 per cent of patients with SNHL had moderate or severe hearing loss. Many of these patients were referred for a hearing aid in the clinic; none were referred for a cochlear implant. In cases of bilateral profound SNHL, early cochlear implantation is an important consideration, before the onset of labyrinthitis ossificans, which may compromise full insertion and patient outcome.

Cerebrospinal fluid leak

A greater proportion of patients with non-otic capsule sparing fractures than with otic capsule sparing fractures developed a CSF leak (30 per cent vs 8.1 per cent, respectively). Reports within the literature show an 8-fold increase in CSF leaks amongst the non-otic capsule sparing fracture cohort,Reference Little and Kesser8 but our figures were not significant for this (p = 0.075). Only one patient required CSF leak repair following fracture to the anterior skull base, but the details of this are unclear from the records. Some evidence recommends surgical repair in all cases of CSF leak, in order to prevent the onset of meningitis, which may occur up to three years following initial injury.Reference Magliulo, Appiani, Iannella and Artico16 This is thought to be secondary to poor healing of endochondral bone.Reference Adkins and Osguthorpe17

Conservative management

The use of prophylactic antibiotics to reduce the risk of meningitis is controversial. In our series, patients with a CSF leak were no more likely to be given antibiotics than those without a CSF leak. Those with concurrent infection are treated with prophylactic antibiotics. However, there are well known arguments against their use, including avoiding the masking of early meningitis signs.Reference Patel and Groppo18 In contrast, many studies support the use of antibiotics in patients with concurrent infection or lacerations.Reference Brodie and Thompson4,Reference Nishiike, Miyao, Gouda, Shimada, Nagai and Nakagawa13 A 2011 Cochrane review that examined evidence from 208 patients from 5 randomised, controlled trials (RCTs) did not demonstrate any significant difference between antibiotic prophylaxis groups and control groups in terms of meningitis or ongoing CSF leak. This conclusion is also supported by non-RCT data.Reference Ratilal, Costa, Sampaio and Pappamikail19

Surgical repair

The majority of CSF leaks close spontaneously within one week. The optimal timing of surgical repair is debated. Some centres advocate repair within 7 days, in light of evidence of a reduction in meningitis risk in this timeframe.Reference Brodie and Thompson4 In our centre, surgical repair is generally performed at around two weeks, following joint discussion with the neurosurgery department. Discussion points include the trial of a lumbar drain, and consideration of other factors such as: patient's symptoms, degree of leakage, fitness for surgery, status of hearing in the contralateral ear, brain herniation through the tegmen, patency of the ear canal and the location of the fistula. However, within the time frame studied, we had no cases that required surgical exploration.

Surgical techniques vary depending on the clinical scenario. For patients with profound SNHL, blind sac closure is recommended.Reference Kveton20–Reference Diaz, Cervenka and Brodie22 Patients with intact hearing and tegmen defects may undergo repair via a mini-craniotomy or an extradural middle cranial fossa approach.Reference Adkins and Osguthorpe17 Larger defects may be repaired using an intradural approach.Reference Glasscock, Dickins, Jackson, Wiet and Feenstra23 Cases may require neurosurgical assistance; it is therefore important that patients are managed at the appropriate centre. In patients with CSF leaks arising from the anterior skull base, a transnasal or bifrontal craniotomy approach may also be required.

Facial nerve palsy

Within our series, 5 patients had immediate facial nerve palsy and 20 patients had delayed facial nerve palsy. Patients with non-otic capsule sparing fractures were significantly more likely to have immediate facial nerve palsy compared with patients with otic capsule sparing fractures (p = 0.003). The incidence of facial injury can be five times more likely in non-otic capsule sparing fracture cases.Reference Little and Kesser8

Conservative management

Our results showed that 50 per cent of patients with delayed facial nerve palsy (10 out of 20) were administered high-dose steroids, compared to only one patient with immediate facial nerve palsy.

Results from the ‘CRASH’ (corticosteroid randomisation after significant head injury) trial (which involved more than 10 000 patients from across 49 countries) demonstrated that high-dose steroid use is contraindicated in patients with traumatic brain injury because of a significantly increased mortality rate.Reference Edwards, Arango, Balica, Cottingham, El-Sayed and Farrell24 Subsequently, the 2005 Cochrane review advised against steroid use in this patient population.Reference Alderson and Roberts25 The patients in the trial were randomised to a 2 g loading dose plus a 400 mg maintenance dose of methylprednisolone within 48 hours of injury. Although steroid use in the context of facial palsy within ENT is generally far more conservative (generally only doses of up to 60 mg of prednisolone), it is important to exercise caution when prescribing high-dose steroids in this patient population, based on this evidence.

Surgical management

It is largely accepted that patients with delayed facial nerve palsy will make a complete recovery.Reference Dahiya, Keller, Litofsky, Bankey, Bonassar and Megerian3,Reference Brodie and Thompson4 It has been reported that in some cases recovery is achieved in only 94 per cent of patients.Reference Turner26 One case report describes facial nerve transection during exploration of the nerve.Reference May27

Injury to the facial nerve can be due to an avulsion injury or compression from comminuted bony fragments, and can occur anywhere between the internal auditory meatus and the vertical portion of the facial nerve. The area most commonly affected is the peri-geniculate region and the medial aspect of the middle ear where it is most susceptible to injury.Reference Fisch28–Reference Coker, Kendall, Jenkins and Alford30 A large series of 65 patients with trauma-related facial palsy (52 had immediate facial nerve paralysis) found that 66 per cent of injuries occurred at the peri-geniculate ganglion and 13 per cent of injuries resulted in a nerve gap.Reference Darrouzet, Duclos, Liguoro, Truilhe, De Bonfils and Bebear31

Surgical repair of the facial nerve is controversial. Such treatment is dependent on a number of factors, including: the decision to operate, the timing of surgery and the surgical approach used (based on injury location). Fisch advocates repair as soon as possible, once more than 90 per cent Wallerian degeneration has been demonstrated on electroneuronography (ENoG, see discussion below).Reference Beck and Benecket32–Reference Shelton and Shelton34 A translabyrinthine approach may be utilised in patients with profound SNHL. Middle cranial fossa or transmastoid approaches may be used in patients with preserved hearing.Reference Shelton and Shelton34 Expected recovery rates following decompression are estimated to be around 55 per cent.Reference Johnson, Semaan and Megerian35 One series describing the conservative management of immediate facial nerve palsy reported good recovery rates in less than 60 per cent of patients. In practice, this may complicate decision making in cases that present to ENT beyond two to three weeks. The two most important factors in considering facial nerve decompression or repair are the severity of the injury and the delay of onset. In some patients, it is more appropriate to undergo facial nerve reanimation using dynamic or static techniques. This is usually performed within two years of injury and requires multidisciplinary input. Non-operative techniques include Botox® injections and physiotherapy.Reference Gordin, Lee, Ducic and Arnaoutakis36

Information from three patients in our series who underwent surgical exploration was retrieved. In the first case, intra-operative findings showed bony spicules embedded in the geniculate ganglion. These spicules were removed, but facial function remained poor, with synkinesis affecting all muscle groups. The patient underwent a trial of Botox injections, but recovery remained limited and the patient was referred for consideration of muscle transfer.

In the second case, there was a severed nerve in the descending portion, and the patient underwent a sural nerve interposition graft at five months post-injury. Subsequent canalplasty was performed in light of intractable granulation tissue within the fractured floor of the external ear canal. Facial nerve recovery was also poor and the patient was referred to the plastic surgery department for consideration of facial nerve reanimation.

In the third case, the patient had probable immediate House–Brackmann grade VI bilateral facial nerve palsies. At four weeks post-injury, the patient underwent electromyography (EMG), which revealed ‘profuse spontaneous activity in facial nerve muscles bilaterally without recordable motor unit action potentials under voluntary control’. At two months post-injury, the patient underwent left-sided facial nerve decompression (vertical portion to first genu). The incus was found pushed in toward the first genu and was decompressed (plus ossiculoplasty). Marginal bilateral improvement was achieved at four months post-operation, on the operated and non-operated side. The patient has since made further recovery, with House–Brackmann grades improving to grade II bilaterally.

In all of the above cases, intervention was delayed beyond the two-week window because of co-existent injury, and ENoG was not used.

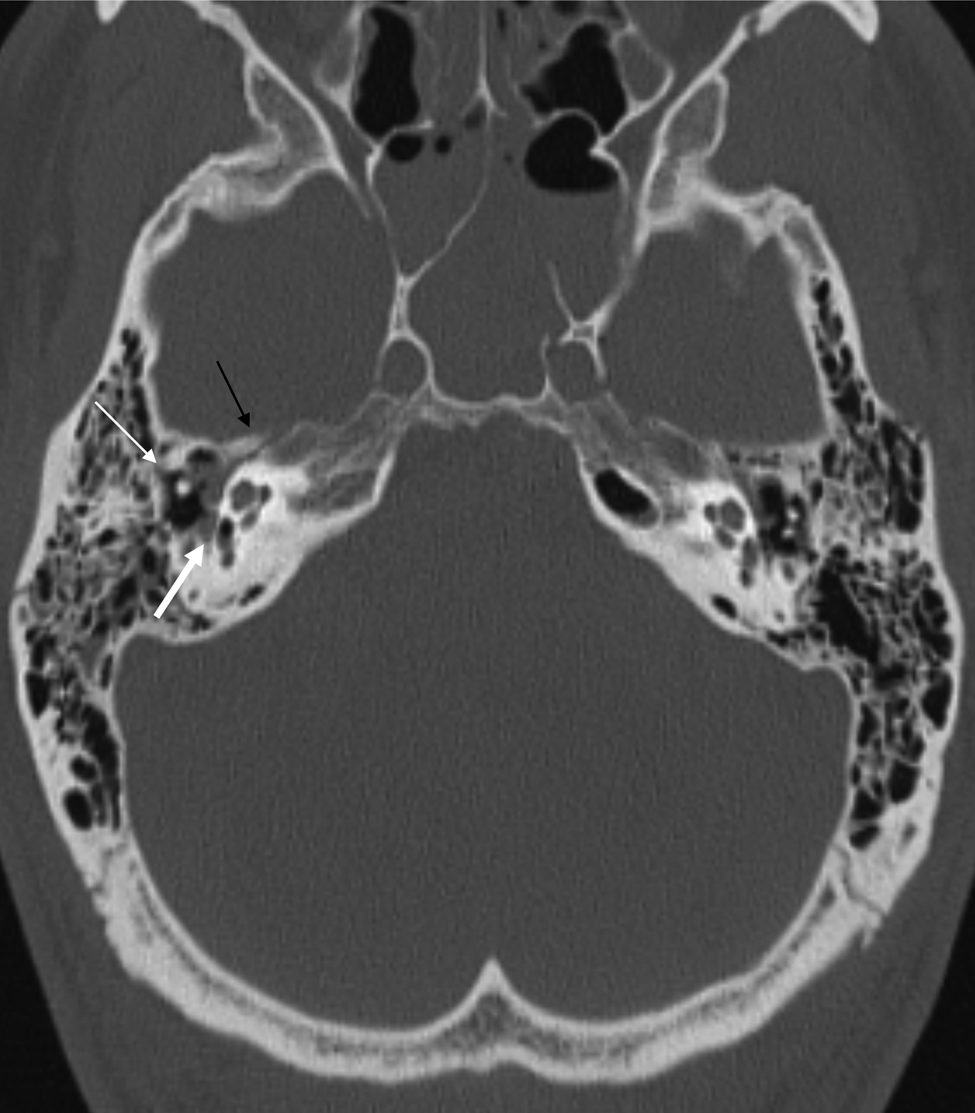

Figure 2 demonstrates evidence of ossicular dislocation, a fracture through the facial nerve canal and pneumolabyrinth in a patient who fell from a height of 20 feet (6 metres).

Fig. 2. Axial, non-contrast computed tomography scan of a patient who sustained a fall from 20 feet (6 metres), showing a non-otic capsule sparing fracture of the right temporal bone. The thin white arrow indicates an absent incus, the black arrow demonstrates a fracture line through the facial nerve canal, and the thick white arrow shows pneumolabyrinth.

Role of nerve conduction studies

Electroneuronography and EMG are objective tests of facial nerve function, and are helpful in guiding treatment and determining prognosis following facial nerve injury.Reference Mannarelli, Griffin, Kileny and Edwards37 In short, ENoG is an evoked EMG; it records nerve conduction distal to the site of injury, by measuring muscle response to an electrical stimulus.Reference Gantz, Rubinstein, Gidley and Woodworth38 It is able to distinguish between first-degree injuries (i.e. neuropraxia) and injuries that have developed Wallerian degeneration (second-degree to fifth-degree injuries). The speed of the onset of Wallerian degeneration is proportional to the severity of injury. Fisch established that Wallerian degeneration was complete by 3–5 days in fifth-degree injuries (complete nerve transection), but took less than 21 days in second-degree injuries (axonotmesis).Reference Fisch39

It is generally accepted that patients with a positive ENoG test result who have more than 90 per cent Wallerian degeneration are more likely to develop incomplete recovery. This evidence predates the House–Brackmann facial nerve grading system, making it difficult to compare the quoted positive predictive value of 91 per cent with figures reported in more recent studies.Reference House and Brackmann40 Gantz et al. has demonstrated 100 per cent recovery to House–Brackmann grades I or II in cases where ENoG studies showed a negative result.Reference Gantz, Rubinstein, Gidley and Woodworth38

It is advised that EMG be performed at 10–14 days post-injury to allow for abnormal healing or resting potentials to occur. In traumatic cases where there is commonly a delay in performing nerve conduction studies (because of the initial treatment of immediately life-threating injuries), an EMG may be more suitable than ENoG. However earlier investigation should be conducted when possible, as a delay of 10–14 days may impact nerve recovery. If any electrical activity is demonstrated on EMG then nerve transection is ruled out.Reference Mannarelli, Griffin, Kileny and Edwards37

The decision to perform nerve conduction studies varies widely in the UK. This may be because of surgeon preference or a lack of equipment availability. Some surgeons are reassured that a negative ENoG finding and voluntary muscle activity are sufficient to indicate that a patient will have a high probability of regaining normal or near-normal function, and therefore does not require surgical exploration or repair.Reference Gantz, Rubinstein, Gidley and Woodworth38 Other surgeons rely on high-quality imaging alongside a convincing history when deciding whether to operate, thus potentially limiting its value in the acute setting. At our centre, we are more likely to rely exclusively on imaging to guide decisions regarding surgery, particularly when the clinical case is unclear.

Other symptoms

A number of other clinical features seen within our series included: BPPV (7 patients), vertigo (15 patients); ear canal stenosis (2 patients), and hyposmia or anosmia (5 patients). These findings have been well documented in the literature. The onset of post-traumatic BPPV following temporal bone fracture is not uncommon, and central balance disturbance may occur following brainstem injury (because of vestibular nuclei damage).

One patient with a historic otic capsule sparing fracture, whose data were not included in the series (the injury preceded 2012) demonstrated middle-ear and attic cholesteatoma secondary to the trapping of squamous epithelium behind a healed perforation.

Other injuries resulting from a temporal bone fracture can include damage to Meckel's cave (leading to abducens and/or trigeminal nerve dysfunction) or vascular injury.

• Temporal bone fractures represent high-energy trauma; initial management focuses on patient stabilisation and intracranial injury treatment

• Acute ENT intervention is directed towards managing facial palsies and cerebrospinal fluid leaks, and often requires multidisciplinary team input

• The role of nerve conduction studies in immediate facial palsy is variable across the UK

• High-dose steroid administration is not advised in patients with temporal bone fracture and intracranial injury

• A robust evidence-based approach for managing ENT complications associated with temporal bone fractures is introduced, to optimise patient care

• Management options should focus on hearing optimisation, and cholesteatoma and ear canal stenosis treatment

Protocol

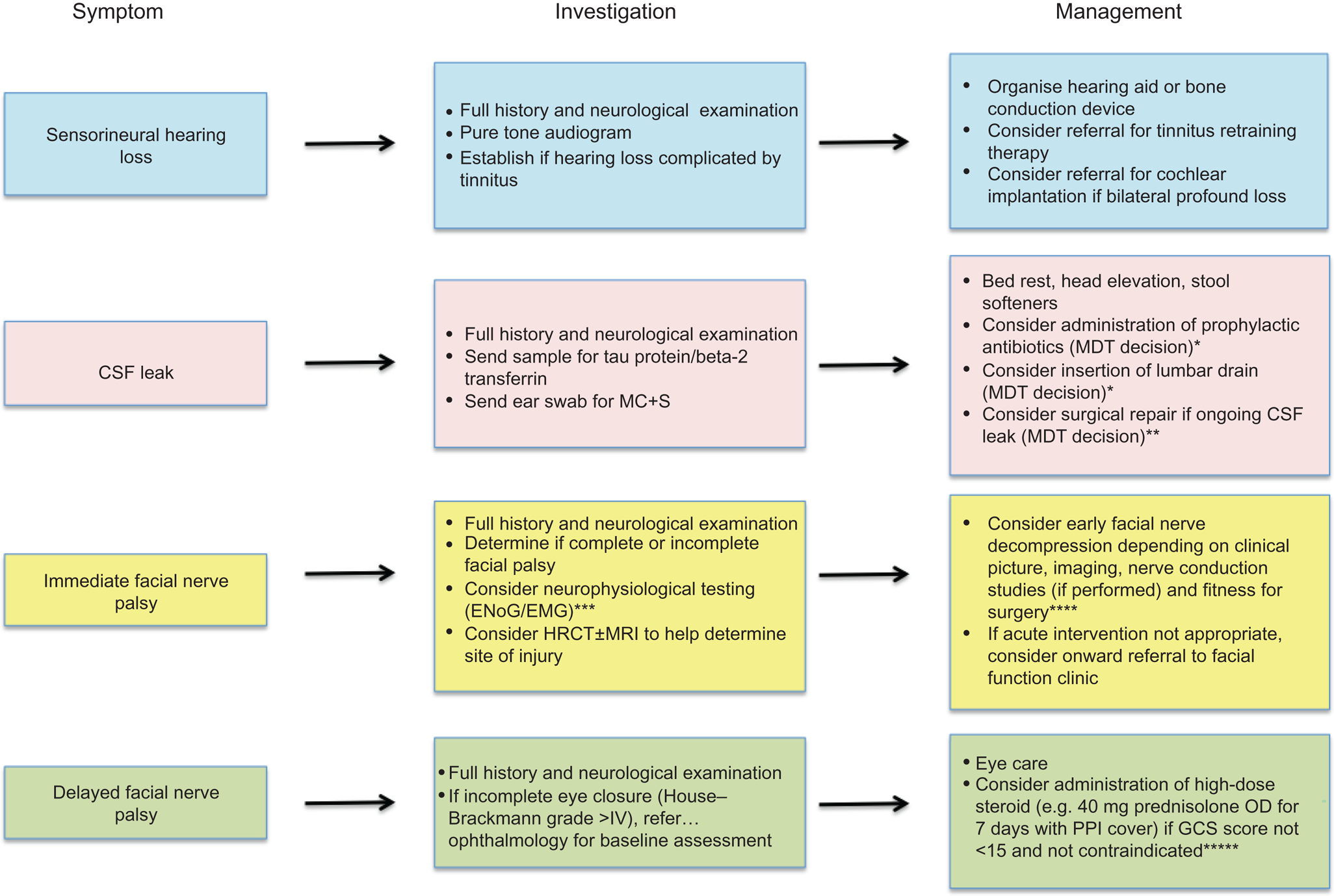

Using our case series findings and published international data, we developed a robust evidence-based protocol for the management of temporal bone fractures (Figure 3). The methods of managing other ENT complications associated with temporal bone fractures are shown in Table 3.

Fig. 3. Management protocol for significant ENT complications following temporal bone fracture. *Encouraged if evidence of concurrent infection, as this may increase risk of meningitis.Reference Brodie and Thompson4,Reference Nishiike, Miyao, Gouda, Shimada, Nagai and Nakagawa13 **Surgical repair dependant on fitness for surgery, status of hearing in the contralateral ear, brain herniation through the tegmen, patency of the ear canal and location of the fistula. ***Electroneuronography could be considered at 3 days post-injury and electromyography at 2 weeks post-injury,9 but expertise across centres may vary, including advice on timing of studies. ****Surgical approach will vary according to the location of injury and associated morbidity.Reference Shelton and Shelton34 *****Evidence from the ‘CRASH’ (corticosteroid randomisation after significant head injury) trial shows high-dose steroids are contraindicated in patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of less than 15 because of increased morbidity.Reference Edwards, Arango, Balica, Cottingham, El-Sayed and Farrell24,Reference Alderson and Roberts25 CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; MC + S = microscopy, culture and sensitivity; MDT = multidisciplinary team; ENoG = electroneuronography; EMG = electromyography; HRCT = high-resolution computed tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; OD = once daily; PPI = proton pump inhibitor; GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale

Table 3. Management of other ENT complications associated with temporal bone fracture

OPD = out-patients department; PTA = pure tone audiometry; CT = computed tomography; BPPV = benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

Study limitations

In our study, approximately 80 per cent of electronic patient records (650 out of 704) could not be retrieved, which introduces significant information bias. The lack of clinical data was the result of a number of factors, including: earlier records not being uploaded onto the electronic patient record system, poor clinician compliance with the electronic system, and high levels of patient non-attendance for follow up.

The incidence of temporal bone fractures is likely to have been underestimated, as high-resolution CT, which utilises 0.6 mm slices (compared with 1 mm slices on head CT scans used at our centre), are reported to have a significantly higher detection rate of temporal bone fractures.Reference Manimaran, Sivakumar and Prabu41 Some centres recommend high-resolution CT use in all patients with head trauma.Reference Diaz, Cervenka and Brodie22

Conclusion

Temporal bone fractures represent high-energy trauma. Initial management focuses on patient stabilisation and treatment of associated intracranial injury. Acute ENT intervention is directed towards the management of facial palsy and CSF leak, and often requires multidisciplinary team input. The role of nerve conduction studies in immediate facial palsy is variable across the UK. The administration of high-dose steroids in patients with a temporal bone fracture and intracranial injury is not advised.

Our protocol introduces a robust evidence-based approach to the management of significant ENT complications, in order to optimise care of these patients. Future management options should focus on optimisation of hearing, and treatment of cholesteatoma and ear canal stenosis.

Competing interests

None declared