Introduction

Jugular foramen schwannomas are rare. They represented only 2.9 per cent of all intracranial neuromas encountered at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery over a 20-year period, in a recent review.Reference Tan, Bordi, Symon and Cheesman1 While the nerve of origin can at times be obscure, vagal schwannomas are reported to constitute half such cases, with glossopharyngeal tumours being infrequent.Reference Maniglia, Chandler, Goodwin and Parker2 Imaging findings have led to tumours being classified according to their extracranial, jugular foramen and intracranial components.Reference Franklin, Moore and Fisch3 While intracranial tumours may be more likely to be associated with deafness, ataxia and vertigo, extracranial tumours can present with lower cranial nerve palsies,Reference Kaye, Hahn, Kinney, Hardy and Bay4 although the presentation can be varied and indistinct.Reference Tan, Bordi, Symon and Cheesman1

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia with syncope is an uncommon syndrome and may be due to a neck mass (often malignant),Reference Chalmers and Olson5–Reference Dykman, Montgomery, Gerstenberger, Zeiger, Clutter and Cryer8 vascular compression of the IXth cranial nerve,Reference Ferrante, Artico, Nardacci, Fraioli, Cosentino and Fortuna9, Reference Esaki, Osada, Nakao, Yamamoto, Maeda and Miyazaki10 vascular diseaseReference Alpert, Armbrust, Akhavi, Stamatiou, Killian and De Shazo11 or a foreign body.Reference Al-Ubaidy and Bakeen12 In the majority of cases, the cause is never found.Reference Taylor, Gray, Bicknell and Rees13 In a Mayo Clinic series of 217 cases of glossopharyngeal neuralgia, four presented with syncope.Reference Rushton, Stevens and Miller14 The reported incidence is 0.8/100 000.Reference Katusic, Williams, Beard, Bergstralh and Kurland15

We report below an unusual case of a patient presenting with glossopharyngeal neuralgia and syncope as the result of a jugular foramen schwannoma.

Case report

A 45-year-old woman presented to the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, with syncopal attacks of increasing frequency. In the previous two months, she reported suffering six episodes beginning with a sharp pain affecting her left ear, throat and neck. When sleeping on her left side, she would awake with pain feeling nauseous and dizzy. Her light-headedness worsened with head movements to the left. She would then faint, with impaired consciousness for 5–10 minutes. There was no history of seizures. There were no problems with the patient's voice or swallowing, and she did not complain of tinnitus.

On examination, there was very slight medial displacement of the patient's left tonsil. No mass was palpable in her neck, and there were no cranial nerve palsies.

An electrocardiogram revealed heart block. Further autonomic testing found that, with prolonged head-up tilt, the patient had a fall in blood pressure and heart rate. Orthostatic hypotension and postural tachycardia syndrome were excluded. Carotid massage, stimulation over various parts of the pharynx, and swallowing all failed to elicit changes in blood pressure or heart rate.

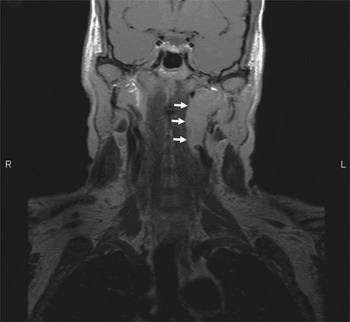

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 2.7 × 2.7 × 4.5 cm mass within the carotid space which extended superiorly to the pars nervosa of the jugular foramen and which had the imaging characteristics of a schwannoma. The internal jugular vein was partially effaced (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 T1-weighted coronal magnetic resonance imaging scan showing schwannoma (arrowed) within the parapharyngeal space and abutting the jugular foramen. R = right; L = left

The schwannoma was resected via an extended cervical incision, following precautionary insertion of a temporary cardiac pacing wire lest there be any peri-operative arrhythmias. At surgery, it was immediately apparent that the vagus was not the origin of the tumour, as it was displaced laterally over its surface (Figure 2). The tumour extended into the jugular foramen and was removed completely in a piecemeal fashion so that collateral damage to adjacent neural structures was minimised. The nerve of origin could not be positively determined, but identification was made via a process of exclusion, by identifying the other carotid sheath structures. The schwannoma seemed most likely to be arising from the glossopharyngeal nerve. Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of a World Health Organization grade one schwannoma.

Fig. 2 Surgical photograph showing the schwannoma (bottom arrow) lying medial to the internal jugular vein, which is held in a vascular sling. The hypoglossal nerve (upper arrow) is crossing the bifurcation of the carotid arteries, and the vagus (middle arrow) is seen running over the capsule of the schwannoma.

In the post-operative period, the resection was complicated by a partial and temporary ptosis, and the patient experienced mild dysphagia which subsequently improved significantly. She also had impaired sensation in the distribution of the glossopharyngeal nerve within the oropharynx, which persisted.

At the time of writing, the patient had not suffered any further syncopal attacks, and a post-operative MRI scan had confirmed complete removal of the tumour.

Discussion

Jugular foramen schwannomas arise in the medial compartment of the foramen, the pars nervosa, which contains the IXth, Xth and XIth cranial nerves.Reference Gleeson and Scott-Brown16 Symptoms and signs include decreased pharyngeal sensation, impaired gag reflex, palatal deviation, vocal fold palsy with abnormal phonation, sternocleidomastoid and trapezius weakness, deafness, tongue atrophy, hemifacial spasm, ataxia, and hydrocephalus.Reference Tan, Bordi, Symon and Cheesman1 Imaging confirms a lesion related to the jugular foramen but cannot determine the cranial nerve of origin. A classification scheme has been proposed to aid surgical planning and management.Reference Franklin, Moore and Fisch3

In 1910, WeisenburgReference Weisenburg17 described the occurrence of glossopharyngeal pain in a patient diagnosed at post mortem with a cerebellopontine angle sarcoma. The term glossopharyngeal neuralgia was used in 1921 by Harris,Reference Harris18 who noted in his paper that Sicard of France had described three similar cases which were treated by nerve section in the neck. In 1942, RileyReference Riley, German, Wortis, Herbert, Zahn and Eichna19 was the first to report two cases with glossopharyngeal neuralgia, cardiac arrest, syncope and seizures; he described the glossopharyngeal–medullary–vagal ‘reflex arc’ as the source of the syndrome, and stated it could be blocked by ‘cocainization of the throat’ and ‘atropinization of the vagus’. Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Gray, Bicknell and Rees13 and St JohnReference St John20 reviewed a total of 35 cases over the next 40 years.

Chalmers and OlsonReference Chalmers and Olson5 described 12 cases of glossopharyngeal neuralgia syncope syndrome (also called vagoglossopharyngeal neuralgia) with neck masses; these included five from St John's review, five new casesReference Dykman, Montgomery, Gerstenberger, Zeiger, Clutter and Cryer8, Reference Sobol, Wood and Conoyer21, Reference Weinstein, Herec and Friedman22 and two cases of their own. The neck masses in question comprised nine malignancies, two abscesses and one haematoma. Although a rare clinical syndrome, the importance of glossopharyngeal neuralgia syncope syndrome is exemplified by further reported cases of neck malignancy with syncope and glossopharyngeal neuralgia as the presenting features.Reference Worth, Stevens, Lasri, Brew, Reilly and Mathias6, Reference Kim, Lal and Ruffy7 Similarly, in our patient glossopharyngeal neuralgia syncope syndrome was the sole presentation of a jugular foramen schwannoma.

The key features of glossopharyngeal neuralgia syncope syndrome are unilateral throat, neck or ear pain triggered by swallowing, chewing, coughing, yawning or head movement, with ensuing syncope and seizures, hypotension, and asystole or bradycardia.Reference Alpert, Armbrust, Akhavi, Stamatiou, Killian and De Shazo11 Cardiac arrest has been reported to last up to 35–40 seconds.Reference Barbash, Keren, Korczyn, Sharpless, Chayen and Copperman23 Parotid hypersecretion has also been described.Reference Kjellin, Mueller and Widen24 In some cases, local anaesthetic applied to the sensitive area in the pharynx can prevent the attack and confirm the diagnosis. Patients with the syndrome have also described a ‘tickling sensation’ in the throat prior to syncope, as opposed to neuralgia.Reference Reddy, Hobson, Gomori and Sutherland25

In our patient, symptoms were triggered by lying on the left side and turning to the left. A positional trigger has also been described in other cases.Reference Sobol, Wood and Conoyer21, Reference Barbash, Keren, Korczyn, Sharpless, Chayen and Copperman23

Cicogna et al. Reference Cicogna, Bonomi, Curnis, Mascioli, Bollati and Visioli26 have described a similar presentation in a series of 11 patients with a parapharyngeal lesion; however, glossopharyngeal neuralgia was not a feature and there was no obvious trigger. They termed this phenomenon parapharyngeal space lesion syncope syndrome.

Carotid sinus syndrome with bradycardia and hypotension also presents without pain. Hypersensitivity of the carotid sinus is thought to be the cause, and pressure over the carotid sinus the trigger.Reference Weiss and Baker27 Episodes in patients with glossopharyngeal neuralgia syncope syndrome have also been triggered by pressure over the carotid sinus.Reference Alpert, Armbrust, Akhavi, Stamatiou, Killian and De Shazo11, Reference Jamshidi and Masroor28

Central to these three syndromes is an understanding of the carotid sinus reflex, which buffers excessive fluctuations in blood pressure. The sinus nerve of Hering arises from baroreceptors in the carotid sinus and joins the glossopharyngeal nerve conveying impulses to the nucleus of the solitary tract in the medulla. If the sinus pressure is raised, thereby increasing baroreceptor stretch tone, inhibition of medullary vasomotor centres results in peripheral vasodilatation, bradycardia, reduced arterial pressure and changes in cerebral circulation.

Signalling from the nucleus of the solitary tract to the dorsal nucleus of the vagus stimulates a parasympathetic cardio-inhibitory response, causing bradycardia via the vagus nerve while independently suppression of the sympathetic outflow, results in a vasodepressor response with peripheral vasodilation and hypotension.Reference Weiss and Baker27 A decrease in sympathetic drive has been confirmed by measurements showing decreased secretion of plasma catecholaminesReference Dykman, Montgomery, Gerstenberger, Zeiger, Clutter and Cryer8, Reference Barbash, Keren, Korczyn, Sharpless, Chayen and Copperman23 as well as decreased electrical activity in sympathetic nerves during attacks.Reference Wallin, Westerberg and Sundlof29

Fainting and loss of consciousness, as seen in our patient, may be explained by cerebral hypoxia following the bradycardia, asystole or hypotension. However, loss of consciousness and seizures have been described in patients who do not demonstrate a change in heart rate and who remain normotensive. This possibly implies that glossopharyngeal stimulation may have an independent effect on cerebral circulation and oxygenation.Reference Weiss and Baker27, Reference Thomson30

• Jugular foramen schwannomas are rare tumours, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia syncope syndrome is an unusual presentation

• Although tumours of the neck have been implicated in glossopharyngeal neuralgia syncope syndrome, the majority of these have been malignant

• In most cases, this syndrome is treated with a combination of pharmacology and pacing, or with glossopharyngeal nerve section; however, the presented patient was left symptom-free with minimal collateral deficits following removal of the jugular foramen schwannoma

In glossopharyngeal neuralgia syncope syndrome, it is postulated that pain sensation from the oropharynx, also conveyed by the glossopharyngeal nerve, stimulates fibres carrying sensation from the carotid sinus, either via an ephaptic connection peripherally, or via a central connection in the medulla between the nucleus of the solitary tract and the vagal dorsal motor nucleus.Reference Kjellin, Mueller and Widen24, Reference Jamshidi and Masroor28, Reference Wallin, Westerberg and Sundlof29 Ephaptic transmission has been demonstrated experimentally in nerves that are injured or compressed.Reference Granit, Leksell and Skoglund31 Electron microscopic findings have also shown degeneration of the myelin sheath in the glossopharyngeal nerves of patients with glossopharyngeal neuralgia.Reference Ishii32 Alpert et al. Reference Alpert, Armbrust, Akhavi, Stamatiou, Killian and De Shazo11 assumed that, in their patient, ischaemia of the glossopharyngeal nerve in the region of the jugular foramen led to the formation of an abnormal motor–sensory connection, with the trigger being swallowing. Compression of the IXth and Xth cranial nerves at the root entry zone can be caused by vascular loops.Reference Esaki, Osada, Nakao, Yamamoto, Maeda and Miyazaki10 Cicogna et al. Reference Cicogna, Bonomi, Curnis, Mascioli, Bollati and Visioli26 postulated that parapharyngeal space lesions caused syncope via abnormal pressure and stimulation of the glossopharyngeal nerve. Sobol et al. Reference Sobol, Wood and Conoyer21 argued that, in their case, an inflammatory process associated with a malignant tumour and parapharyngeal abscess caused irritation of the glossopharyngeal nerve.

In some cases of glossopharyngeal neuralgia syncope syndrome, atropine can abolish the bradycardia but the hypotension mediated by antisympathetic vasodepressor activity may still persist.Reference Dykman, Montgomery, Gerstenberger, Zeiger, Clutter and Cryer8, Reference Barbash, Keren, Korczyn, Sharpless, Chayen and Copperman23 For this reason, cardiac pacing may also fail.Reference Dykman, Montgomery, Gerstenberger, Zeiger, Clutter and Cryer8, Reference Wallin, Westerberg and Sundlof29 Carbamazepine has been used as the sole treatment to control the pain and syncope,Reference Chalmers and Olson5, Reference Al-Ubaidy and Bakeen12 but has been known to fail after initial success.Reference Taylor, Gray, Bicknell and Rees13, Reference St John20 This drug has also been used in combination with cardiac pacing,Reference Kim, Lal and Ruffy7, Reference Alpert, Armbrust, Akhavi, Stamatiou, Killian and De Shazo11, Reference Barbash, Keren, Korczyn, Sharpless, Chayen and Copperman23, Reference Jamshidi and Masroor28, Reference Johnston and Redding33 but not always successfully.Reference Dykman, Montgomery, Gerstenberger, Zeiger, Clutter and Cryer8, Reference Roa and Krupin34 Other drugs have also been tried, such as diphenylhydantoin,Reference Khero and Mullins35 belladonna extract,Reference Kjellin, Mueller and Widen24 duloxetineReference Giza, Kyriakou, Liasides and Dimakopoulou36 and pregabalin,Reference Savica, Lagana, Calabro, Casella and Musolino37 without much success.

Section of the glossopharyngeal nerve, with or without the upper two rootlets of the vagus, generally produces good results in patients with glossopharyngeal neuralgia syncope syndromeReference Dykman, Montgomery, Gerstenberger, Zeiger, Clutter and Cryer8, Reference St John20, Reference Kjellin, Mueller and Widen24, Reference Roa and Krupin34, Reference Khero and Mullins35 and parapharyngeal space lesion syncope syndrome.Reference Cicogna, Bonomi, Curnis, Mascioli, Bollati and Visioli26 Successful outcomes have also been reported following microvascular decompression.Reference Ferrante, Artico, Nardacci, Fraioli, Cosentino and Fortuna9, Reference Esaki, Osada, Nakao, Yamamoto, Maeda and Miyazaki10

In patients with benign neck masses, such as our reported case, successful outcomes may involve removal of the mass.Reference Sobol, Wood and Conoyer21 Temporary cardiac pacing has been used while awaiting surgery, and may be necessary to manage peri-operative arrhythmia,Reference Esaki, Osada, Nakao, Yamamoto, Maeda and Miyazaki10, Reference Roa and Krupin34 as in our case.

Conclusion

The case presented is unusual in that jugular foramen schwannomas are rare tumours and glossopharyngeal neuralgia syncope syndrome is an unusual presentation. Although tumours of the neck have been implicated in glossopharyngeal neuralgia syncope syndrome, the majority of these have been malignant. In most cases, this syndrome is treated with a combination of pharmacology and pacing, or with glossopharyngeal nerve section. However, the presented patient was left symptom-free and with minimal collateral deficits following removal of her jugular foramen schwannoma.