Introduction

Balance control involves a complex system of co-ordinated muscular responses, input from the somatosensory system, and a combination of vestibular and visual information. Dizziness, vertigo and imbalance are common complaints in both emergency and non-acute medicine, and account for 1–2 per cent of consultations among out-patients in general practice.Reference Ekvall Hansson, Mansson and Hakansson1,Reference Hanley, O'Dowd and Considine2

Problems with dizziness and imbalance become more prominent with increasing age. Approximately 20–40 per cent of the elderly suffer from balance problems,Reference Kollén, Horder, Moller and Frandin3–Reference Kollén, Frandin, Moller, Fagevik Olsen and Moller8 with females being more frequently affected than males.Reference Kollén, Frandin, Moller, Fagevik Olsen and Moller8,Reference Grimby and Rosenhall9 Dizziness in advanced ages is so common that it is sometimes considered part of the natural ageing process and a geriatric syndrome.Reference Kao, Nanda, Williams and Tinetti6,Reference Rosso, Eaton, Wallace, Gold, Stefanick and Ockene10

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the single most common cause of vestibular dizziness.Reference Furman and Cass11 It is caused by utricular otoconia that has been displaced into the semicircular canals, causing canal-specific nystagmus when tested. The posterior canal is most commonly affected, followed by the horizontal canal. Sleep and time in bed appear to be of importance, as many patients experience their first episode of vertigo in the morning, and dizziness when turning over in bed is highly correlated to BPPV.Reference von Brevern, Radtke, Lezius, Feldmann, Ziese and Lempert12,Reference Noda, Ikusaka, Ohira, Takada and Tsukamoto13 The epidemiology of BPPV is not fully known and demographic analyses are few.

The incidence of BPPV varies in studies, ranging from 10 to 17 per 100 000 per year,Reference Mizukoshi, Watanabe, Shojaku, Okubo and Watanabe14 with a prevalence of 1.4–2.4 per cent.Reference von Brevern, Radtke, Lezius, Feldmann, Ziese and Lempert12,Reference van der Zaag-Loonen, van Leeuwen, Bruintjes and van Munster15 However, prevalence of unrecognised BPPV among the elderly has been reported to be as high as 9–11 per cent.Reference Kollén, Frandin, Moller, Fagevik Olsen and Moller8,Reference Oghalai, Manolidis, Barth, Stewart and Jenkins16 The duration of dizziness and the symptoms provoked by head position changes have been shown to be useful for detecting BPPV, and of value in epidemiological surveys.Reference von Brevern, Radtke, Lezius, Feldmann, Ziese and Lempert12

The use of medications among older adults has increased dramatically over the last 20 years.Reference Craftman, Johnell, Fastbom, Westerbotn and von Strauss17 Currently, more than 40 per cent of people in Sweden aged over 65 years regularly take 5 or more medications.Reference Morin, Fastbom, Laroche and Johnell18 The use of five or more medications is often considered as polypharmacy.Reference Haider, Johnell, Weitoft, Thorslund and Fastbom19 The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare considers this a risk for: inappropriate use, high mortality and falling among the elderly.20,Reference Ziere, Dieleman, Hofman, Pols, van der Cammen and Stricker21 Imbalance in the elderly may have serious consequences, including an increased risk of falling, an impaired quality of life, and reduced physical exercise and activities.Reference Kollén, Horder, Moller and Frandin3,Reference Grimby and Rosenhall9,Reference Weidt, Bruehl, Straumann, Hegemann, Krautstrunk and Rufer22,Reference Ekwall, Lindberg and Magnusson23

Many studies have reported dizziness in the elderly established by positional changes, but few investigated the participants for nystagmus indicating BPPV using Frenzel goggles. This study aimed to investigate the rate of self-reported dizziness in the elderly when lying down or turning over in bed, and to examine for BPPV by physical examination in those reporting dizziness when lying down or turning over in bed. Additional aims included establishing the presence of self-reported dizziness and impaired balance, and examining the intake of medications among citizens aged 70–85 years.

Materials and methods

Study population

Details of residents aged 70–85 years, living in the uptake area of the secondary emergency Southern Älvsborg Hospital, were obtained from the national registration registry. The residents were contacted during 2015 by postal mail and asked to complete a questionnaire (Table 1). Given the semantic risk of misunderstanding and distinguishing ‘dizziness’ from ‘unsteadiness’, the two questions on these symptoms were merged together as a main outcome.

Table 1. Study-specific questionnaire

The questionnaires were sent to 498 people, of which 50 per cent were male and 50 per cent were female. Residents who did not reply were reminded once after four weeks. Only people who returned the questionnaires were included in the study.

The questions were related to dizziness and its triggers and character, and relevant healthcare-seeking behaviour. The questions were chosen and formulated based on literature, clinical expertise and comments from patients, and have been used in clinical practice at the study hospital for many years.

Study design

In this cross-sectional study, the participants completed a study-specific questionnaire (Table 1) and were asked to list their medications. Persons who answered that they experienced dizziness when lying down or turning over in bed were considered as possibly having BPPV. These individuals received an invitation to undergo a clinical investigation for vertigo and dizziness by an ENT specialist, using the Video Frenzel System (video nystagmoscopy VNS3X goggles; Synapsys, Marseille, France), at the ENT clinic at Southern Älvsborgs Hospital, Sweden.

The physical examination included tests for BPPV, such as the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre and the supine roll test. Examination also included the head shake test, head impulse test, testing for spontaneous or gaze-evoked nystagmus, cranial nerve testing, and otoscopic examination. The diagnosis of BPPV was confirmed only if the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre or supine roll test triggered vertigo and simultaneous canal-specific nystagmus.Reference von Brevern, Bertholon, Brandt, Fife, Imai and Nuti24

In the cases where BPPV was found, the patients were treated with the Epley manoeuvre for posterior canal BPPV and the Gufoni manoeuvre for horizontal canal BPPV. If symptoms persisted after treatment, the patient was invited to return to the ENT department for a second investigation. The time from questionnaire completion to clinical examination ranged from two to four months.

Statistical analysis

The main outcome of dizziness or unsteadiness by gait was defined as: problems with dizziness or being unsteady when standing or walking.

For comparisons between two groups, the Fisher's exact test was used for dichotomous variables, the chi-square test was used for non-ordered categorical variables and the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for continuous variables. For comparisons between more than two groups, the chi-square test was used for non-ordered categorical variables. For continuous variables, quantity, mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum were presented. For categorical variables, quantity and percentages were presented.

Correlation analyses were performed to assess the relationships between age and polypharmacy and the main outcome measure of dizziness or unsteadiness, using Spearman's test. Odds ratios were calculated for age and polypharmacy in relation to the main outcome of dizziness or unsteadiness, using the largest subcategory as the common reference, together with Wald confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board in Gothenburg, Sweden. All participants gave their informed consent, prior to inclusion in the study.

Results

A total of 498 questionnaires were sent out to citizens aged 70–85 years (male to female ratio of 1:1) for screening of dizziness and balance problems. A total of 324 participants (65 per cent) completed the questionnaire, of which 165 (51 per cent) were male and 159 (49 per cent) were female (Table 2). Of the 174 non-responders (35 per cent), the reasons were: incorrect address or delivery failure (n = 8), incapacity to participate (n = 4), deceased (n = 3), did not want to participate (n = 2) or did not give any reason (n = 157). There were no significant differences in terms of age or gender between the subjects not returning the questionnaire and those included in the study. No differences were found regarding the group who attended for examination and the rest of the survey participants (gender p = 0.076, age p = 0.49). The median and mean age of respondents was 76 years.

Table 2. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study cohort

* P-values represent gender differences

Of the respondents, 92 (29 per cent) reported dizziness. Dizziness or unsteadiness by gait was reported more often than dizziness associated with positional changes (Table 2). All types of reported dizziness symptoms were significantly more predominant among female subjects (Table 2). Furthermore, female participants had sought medical care for dizziness more often than males.

Supine dizziness and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

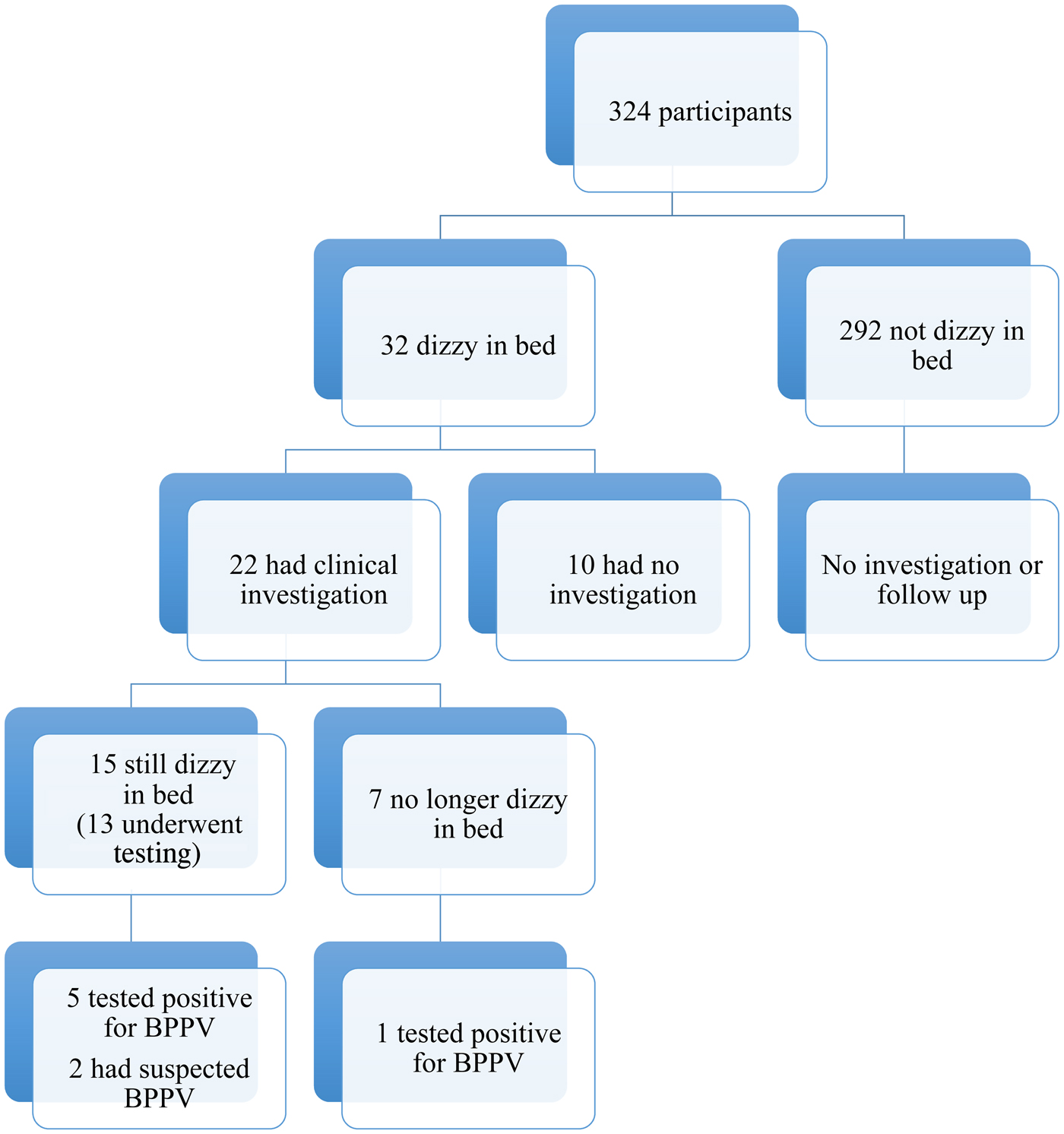

Of the respondents, 10 per cent (22 females and 10 males) reported positional dizziness, and became dizzy when lying down or turning over in bed. These participants were invited for a diagnostic evaluation, and 22 of these individuals (69 per cent) attended the ENT clinic for investigation (Figure 1). Reasons for not attending were: illness or current hospitalisation (n = 8), and no reply (n = 2).

Fig. 1. Flow chart of study participants. BPPV = benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

Of the 22 individuals who came for the physical examination, 15 reported current dizziness (always or sometimes) when turning or lying down in bed. Two females reported such strong dizziness when turning over or lying in bed that they had discontinued lying down, and instead slept in a seated position. They consequently refused examination using positional tests in light of the potential risk of becoming dizzy; these two individuals were suspected of having possible BPPV.

Of the 13 subjects investigated with the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre and supine roll test who still experienced dizziness when turning or lying down in bed, 5 tested positive for BPPV according to the Bárány Society criteria. Of the remaining eight individuals reporting dizziness in bed, three females reported dizziness when turning over in bed sometimes, but not always, of which one had BPPV at re-examination a few weeks later. One individual reported dizziness during all positional changes and had signs of vestibular hypofunction at follow up with caloric irrigation. Four patients reported general unsteadiness with positional symptoms, but which was most prominent when rising up from a supine position, indicating possible postural hypotension.

Of the seven subjects no longer reporting dizziness in bed at the clinical examination, one tested positive for BPPV with nystagmus and vertigo, using the Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre, and six no longer had positional symptoms or other symptoms of dizziness. One male reported general unsteadiness and imbalance by gait, but no positional symptoms. None of the examined subjects had pathological findings on the head shake test, nor spontaneous nystagmus. One male with general unsteadiness had signs of gaze-evoked nystagmus. Posterior canal BPPV was detected in five subjects and horizontal canal BPPV was found in one subject, with a gender distribution of five females to one male.

Dizziness and age

Dizziness and unsteadiness by gait in the elderly showed gender differences. Dizziness increased significantly with age among males, but not among females (Table 3). For both genders, the odds ratio of experiencing dizziness was 2.85 (standard deviation = 1.59–5.10, p < 0.001) in those aged 80–84 years compared to those 70–74 years old.

Table 3. Dizziness or unsteadiness by gait categorised by age

Of the 324 participants, 139 reported problems with dizziness and/or unsteadiness of gait, of which 30 per cent had sought medical care because of dizziness.

The mean age among participants reporting dizziness was 78.5 years in males versus 77.5 years in females, with a median of 79 years in males versus 76 years in females. No significant gender difference regarding the age of the participants in total was found.

Dizziness and polypharmacy

Eighty-five per cent of the participants reported daily use of medications, and 36 per cent (111 out of 305) reported daily use of five or more medications (Table 4). Of the patients reporting using five or more medications, 58 per cent (64 out of 111) reported problems with unsteadiness and/or dizziness (Table 4). Dizziness and unsteadiness by gait significantly increased with increasing numbers of medications (p = 0.0004). However, polypharmacy in itself did not significantly increase with age.

Table 4. Number of medications by reported dizziness or unsteadiness by gait

* Data missing for 19 participants

The odds ratio of experiencing dizziness or unsteadiness was 1.9 times higher (95 per cent CI = 1.12–3.24, p = 0.017) if receiving 5–8 medications compared to 1–4 medications, and was 4 times higher (95 per cent CI = 1.46–10.88) if receiving 9 or more medications.

There was no significant difference in dizziness between those using no medication versus those taking one to four medications. There was also no significant difference in dizziness if receiving anti-hypertensive drugs including beta blockers and diuretics. No gender difference regarding the prescription of medications was seen.

Discussion

Positional symptoms of dizziness are common, and supine dizziness and vertigo associated with positional change are strongly correlated with BPPV.Reference von Brevern, Radtke, Lezius, Feldmann, Ziese and Lempert12,Reference Noda, Ikusaka, Ohira, Takada and Tsukamoto13,Reference von Brevern, Bertholon, Brandt, Fife, Imai and Nuti24 Asking patients about dizziness experienced when lying down or turning over in bed might be an appropriate means to identify potential BPPV. Every physician should be aware of the possibility of BPPV when a patient reports experiencing dizziness.

The Dix–Hallpike manoeuvre is considered the ‘gold standard’ for detecting posterior canal BPPV. Nevertheless, false-negative results have been reported, and the sensitivity of the test is estimated to be around 80 per cent,Reference Dros, Maarsingh, van der Horst, Bindels, Ter Riet and van Weert25 with higher frequencies of positive findings after repeated manoeuvres;Reference Evren, Demirbilek, Elbistanli, Kokturk and Celik26 hence, there is a risk of false-negative findings in a cross-sectional survey.

This study found that 29 per cent of elderly individuals (aged 70 years or more) had subjective problems with dizziness. In contrast, Oghalai et al.Reference Oghalai, Manolidis, Barth, Stewart and Jenkins16 reported a corresponding rate of 61 per cent. This discrepancy may be explained by the fact that the study populations are vastly different: this study investigated a sample of the general population, and the aforementioned study instead targeted a poor inner-city geriatric population with multiple known co-morbidities. However, the 29 per cent reported here is in line with literature when compared to studies with a similar design or population. Kollén et al.Reference Kollén, Frandin, Moller, Fagevik Olsen and Moller8 and van der Zaag-Loonen et al.Reference van der Zaag-Loonen, van Leeuwen, Bruintjes and van Munster15 reported dizziness rates of 36 per cent (242 out of 675) and 23 per cent (226 out of 989), respectively.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo was found in 27 per cent of patients (6 out of 22) who attended for a clinical examination. This is again similar to the findings of van der Zaag-Loonen et al.,Reference van der Zaag-Loonen, van Leeuwen, Bruintjes and van Munster15 where 29 per cent of participants (13 out of 45) who were examined had BPPV. Kollén et al.Reference Kollén, Frandin, Moller, Fagevik Olsen and Moller8 found BPPV in 11 per cent of their 571 participants who were examined. This discrepancy may be explained by differences in the study design, as Kollén et al. investigated all patients, irrespective of dizziness, whilst this study only examined those reporting dizziness suggestive of BPPV. Additionally, the BPPV diagnostic criteria differed slightly; this study required the presence of canal-specific nystagmus according to the Bárány Society criteria,Reference von Brevern, Bertholon, Brandt, Fife, Imai and Nuti24 whilst the study by Kollén et al. did not. Moreover, the delay between questionnaire completion and the physical examination means that spontaneous resolution of the condition was possible. Nevertheless, we did find BPPV in several subjects, implying that unrecognised BPPV in these age groups exists and may not resolve spontaneously as described previously.Reference Imai, Ito, Takeda, Uno, Matsunaga and Sekine27 Symptoms of positional dizziness are more common than eye motor movements synonymous with BPPV, also reported by others.Reference Kollén, Frandin, Moller, Fagevik Olsen and Moller8 The presence of dizziness showed some gender differences, with female predominance in all aspects of dizziness, and in diagnoses of BPPV.

• Problems with dizziness and imbalance become more common with increasing age

• Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the most common cause of vestibular dizziness; BPPV can go undiagnosed in the elderly

• Many studies have reported dizziness associated with positional changes and when turning over in bed among the elderly, but few have investigated the presence of BPPV

• Positional symptoms were found in 10 per cent of older adults; one-quarter of those fulfilled diagnostic criteria for BPPV

• Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo does not necessarily heal spontaneously in the elderly

The rate of dizziness or unsteadiness significantly increased with increasing numbers of medications. In the present study, no difference in dizziness was found between the intake of anti-hypertensive medication and no medications, even though these types of drugs are considered a risk for orthostatic hypotension, which may cause dizziness.28 A possible reason for the higher number of medications and for the higher rate of dizziness is co-morbidity. Grimby and Rosenhall found 2.7 diagnoses among elderly individuals reporting dizziness, versus 1.7 among those without dizziness.Reference Grimby and Rosenhall9 Hence, dizziness in the elderly could partly be due to the increased number of medications, but this is confounded by the fact that an increased number of medications may be indicative of greater co-morbidity. Nonetheless, physicians should be aware of medications’ side effects and the increased risk of imbalance. They should attempt to limit polypharmacy where possible, but still be observant of possible BPPV, especially when the complaint is dizziness when lying down or turning over in bed.

Limitations

This study is limited by the study design employed, as only participants reporting dizziness in bed were investigated, and not all participants reported dizziness. As such, cases of BPPV may have been missed. In addition, there was a delay between questionnaire completion and the examination, resulting in the possibility of spontaneous resolution of the condition.

Conclusion

Dizziness and unsteadiness are common symptoms among the elderly; approximately 10 per cent report positional symptoms with dizziness when lying down or turning over in bed. When examined, 27 per cent fulfilled diagnostic criteria for BPPV. Furthermore, BPPV was established in patients despite the delay between questionnaire completion and the investigation, suggesting that BPPV does not always heal spontaneously in this age group.

Competing interests

None declared