Introduction

Approximately 10–30 per cent of adults in the USA suffer from rhinitis annually, with nasal congestion identified as the most bothersome symptom.Reference Meltzer, Orgel, Bronsky, Furukawa, Grossman and LaForce1,Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2 For decades, intranasal steroids have been proven to reduce rhinitis, nasal congestion and improve quality of life.Reference Meltzer, Orgel, Bronsky, Furukawa, Grossman and LaForce1,Reference Hallen, Enerdal and Graf3,Reference Wallace, Dykewicz, Bernstein, Blessing-Moore, Cox and Khan4 However, approximately 40–60 per cent of patients fail to achieve symptomatic relief from intranasal corticosteroid spray alone, requiring the need for secondary treatment modalities.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2,Reference Thongngarm, Assanasen, Pradubpongsa and Tantilipikorn5 Consequently, patients may add the over-the-counter medication oxymetazoline hydrochloride nasal spray to their daily regimen as it promotes nasal congestion relief within minutes.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2,Reference Thongngarm, Assanasen, Pradubpongsa and Tantilipikorn5–Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7

Long-term oxymetazoline hydrochloride therapy has been widely known for its potential to cause rebound nasal congestion or rhinitis medicamentosa, which is nasal congestion theoretically caused by inflammation of the nasal mucosa leading to oedema and vasodilation.Reference Lockey8 Per US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance, patients have been advised not to use oxymetazoline hydrochloride for longer than seven days unless otherwise directed by a physician in order to prevent this undesirable outcome from occurring.Reference Wallace, Dykewicz, Bernstein, Blessing-Moore, Cox and Khan4,Reference Passàli, Salerni, Passàli, Passàli and Bellussi9

Recent literature has investigated the outcomes of intranasal corticosteroid spray treatment for rhinitis medicamentosa.Reference Hallen, Enerdal and Graf3 Anecdotally, providers have prescribed intranasal corticosteroid spray with oxymetazoline hydrochloride as a means to prevent rhinitis medicamentosa, although this methodology has not been widely studied enough to standardise an accepted practice in the USA to routinely combine the use of intranasal corticosteroid spray with oxymetazoline hydrochloride.

Zucker et al. recently published a systematic review on management options for rhinitis medicamentosa secondary to oxymetazoline hydrochloride use; they found the literature to be heterogenous in measuring rhinitis medicamentosa symptoms and outcomes after treatment. The authors found the most widely prasticed treatment for rhinitis medicamentosa was intranasal corticosteroid spray.Reference Zucker, Barton and McCoul10 Their study examined patient cohorts that initially presented with rhinitis medicamentosa. To our knowledge, there is not a systematic review on the outcomes of oxymetazoline hydrochloride naïve patients with chronic rhinitis after treatment with intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride combination therapy.

The objective of our study was to determine if the combination of intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride may provide equivalent or superior relief of nasal congestion when compared with intranasal corticosteroid spray alone in oxymetazoline hydrochloride naïve patients presenting with chronic rhinitis. We also seek to determine if intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride therapy may prevent the onset of rhinitis medicamentosa in oxymetazoline hydrochloride naïve patients, which has been speculated in recent literature.Reference Ferguson, Paramaesvaran and Rubinstein11,Reference Vaidyanathan, Williamson, Clearie, Khan and Lipworth12

Materials and methods

Two authors (CLN and CFS) independently and systematically searched the international literature, in all languages, within each database from the inception of study design in September 2016 through to 1 June 2020. The databases searched included: Medline; Cochrane Library; Web of Science; Book Citation Index – Science; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (‘Cinahl’); Scopus; Embase; Google Scholar; and Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science.

An example of a search strategy for Medline is: ‘oxymetaz∗’ together with ‘rhinitis’, ‘allergic rhinitis’, ‘intranasal steroid’, ‘nasal corticosteroid’, ‘rebound congestion’, ‘rhinitis medicamentosa’ or ‘nonallergic rhinitis’. A separate search was also performed in each database with the following search strategy: ‘long term oxymetazoline’, ‘oxymetazoline and nasal steroid’, ‘oxymetazoline for rhinitis treatment’, ‘nasal steroid AND rebound congestion’ or ‘nasal steroid AND rhinitis medicamentosa’.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis statement was followed, whenever applicable, in this review.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman13 Because this was a systematic review, and the searches were in publicly available databases with publicly available articles, the study was exempt from review by the institutional review boards.

Study selection

The inclusion criteria were as follows: the studies selected needed to comprise adolescent or adult patients with continuous chronic rhinitis symptoms for at least 12 months prior to study recruitment. Patients were diagnosed with allergic rhinitis versus non-allergic rhinitis via allergic skin prick testing upon study recruitment. They were either given a combination of intranasal steroid and oxymetazoline hydrochloride spray for a minimum duration of two weeks versus assigned to control group(s) of either oxymetazoline hydrochloride spray, placebo spray or intranasal steroid spray alone. Studies that did not investigate comparison with intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride combination were excluded.

Patients included were at least 12 years old with no pending surgical interventions and were not on nasal medication treatment. Outcome measures included either quality of life scores, nasal rhinometry or patient reported symptoms such as nasal congestion. Quality of life scores were determined based on generic questionnaires looking at fatigue, headache, cognitive impairment and sleep disturbance as a result of the disease process. Nasal rhinometry, a technique that measures functional obstruction to airflow in the upper airway, was used to obtain objective assessment of nasal congestion.Reference Wallace, Dykewicz, Bernstein, Blessing-Moore, Cox and Khan4 Because of the heterogeneity of the four trials used in this manuscript, the cohorts and outcomes were measured differently with different end points. This was something considered when evaluating the data.

Included studies compared baseline data with post-treatment data. The articles, published and unpublished, could be written in any language. Study designs included case-control, case series with chart review, prospective cohorts and randomised controlled trials.

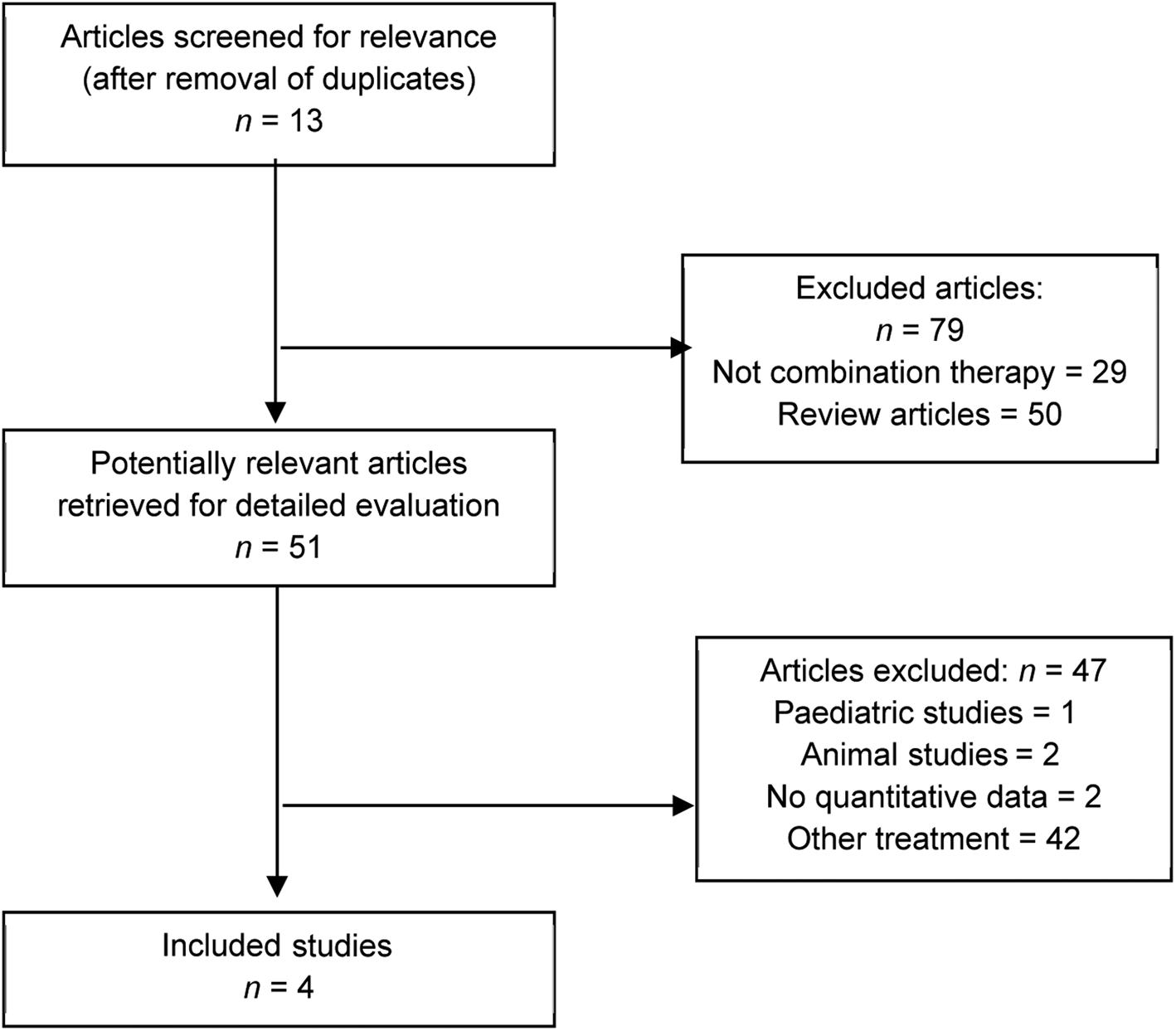

Studies were excluded if: surgical procedure(s) were performed throughout the study period, patients used other nasal sprays throughout the study or patients were diagnosed with rebound congestion from prior oxymetazoline use at the time of recruitment. Studies were also excluded if there were no baseline data or post-treatment data available from patients or control group(s) were lacking from the study. Studies that inclusively investigated paediatric patients (patients under 12 years old) or animals were also excluded from this review. Data from multi-site studies published more than once were only recorded once (i.e. multi-site studies with overlapping results published multiple times) and were otherwise excluded from the results section; however, these may be referenced elsewhere in the paper such as in the discussion. See Figure 1 for flow chart of included studies.

Fig. 1. Study selection flow chart. The search for rhinitis medicamentosa and intranasal corticosteroid spray gave 16 studies (1 animal study, 4 review studies, 3 that were not combination therapy) and 1 met study criteria. The search for oxymetazoline and intranasal corticosteroid spray gave 11 studies (2 review studies, 3 that were not combination therapy, 3 duplicated), and 3 met study criteria. The search for oxymetazoline and rhinitis gave 17 studies (6 review studies, 9 that were not combination therapy, 1 duplicated), and 1 met study criteria. The search for oxymetazoline and nasal corticosteroids gave 12 studies (7 review studies, 1 letter to the editor, 4 that were not combination therapy), and 0 met study criteria. The search for rhinitis medicamentosa treatment gave 87 studies (31 review studies, 1 letter to the editor, 9 that were not combination therapy, 37 other studies, 7 duplicated, 1 paediatric study, 1 animal study), and 0 met study criteria.

Results

Individual study designs

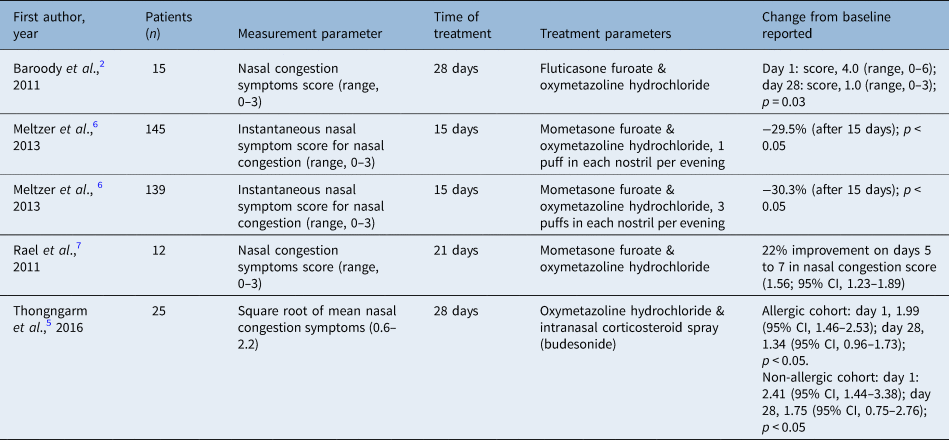

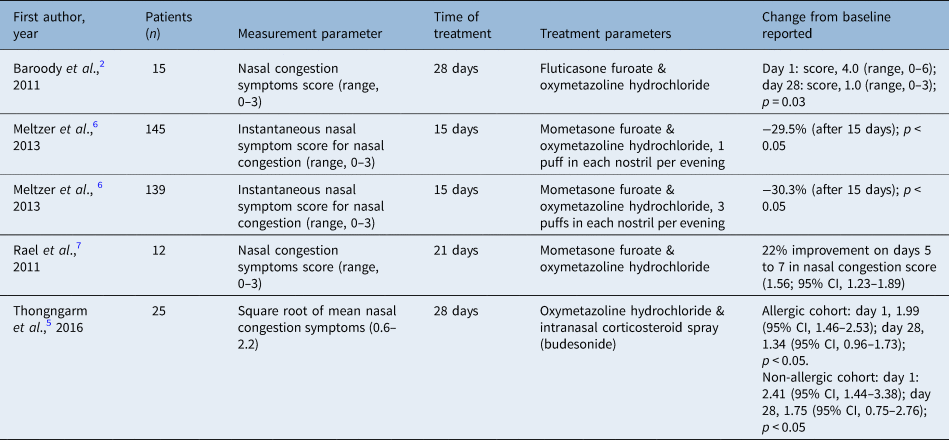

All studies selected were randomised controlled trials, which compared treatment groups with control groups. Each study is summarised in Table 1 to specify which intranasal corticosteroid spray is used with oxymetazoline hydrochloride for the combination treatment arm (medication, dose, frequency). Additionally, Table 1 summarises the major findings of each study.

Table 1. Summary of studies

Quality assessment

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence quality assessment tool was used to determine the quality of the included studies, which is summarised in Table 2.

Table 2. Quality of included studies

Quality assessment of case series studies checklist from National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: 1) Was the case series collected in more than one centre (i.e. multicentre study)? 2) Is the hypothesis, aim or objective of the study clearly described? 3) Are the inclusion and exclusion criteria (case definition) clearly reported? 4) Is there a clear definition of the outcomes reported? 5) Were data collected prospectively? 6) Is there an explicit statement that patients were recruited consecutively? 7) Are the main findings of the study clearly described? 8) Are outcomes stratified? (e.g. by abnormal results, disease stage, patient characteristics)?

Demographic data

The majority of patients (820 of 838) were confirmed via allergy skin prick testing to have allergic rhinitis. Dust mite allergy is the most common allergy reported. Not all studies reported skin prick test results or demographic data. The demographic data for three studies are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3. Demographic information

*Mean age excluding Rael et al. study; †percentage of allergy in patients calculated from 110 results reported overall from Baroody et al.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2 and Thongngarm et al.Reference Thongngarm, Assanasen, Pradubpongsa and Tantilipikorn5. Placebo defined as saline spray or equivalent with no treatment medication given. Oxymetazoline hydrochloride was 0.05%. NR = not reported; N/A = not applicable; SD = standard deviation

Nasal symptoms

Overall, the studies demonstrated that treatment with intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride leads to greater reduction in total nasal symptoms when compared with intranasal corticosteroid spray, oxymetazoline hydrochloride or placebo groups across all four studies (Table 4).

Table 4. Subjective nasal symptoms in intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride treated groups

CI = confidence interval

Baroody et al. demonstrated a lower total nasal symptom score from intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride treatment (median, 143; range, 30–316) when compared with treatment with placebo (median, 262; range, 116–358) or oxymetazoline hydrochloride alone (median, 219; range, 78–385; analysis of variance, p = 0.04) over the 4 weeks of treatment. Additionally, intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride led to greater reduction in total nasal congestion symptom scores than either placebo or oxymetazoline hydrochloride groups alone (p = 0.025). Post hoc analysis demonstrated statistical significance with intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride (p = 0.003).Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2

Meltzer et al. used instantaneous nasal symptom score and total nasal symptom score for assessing nasal symptoms and measured symptoms twice daily (morning and evening) as compared with baseline from days 1 to 15 and days 16 to 22. Results for all active (non-placebo) groups showed improvement from days 1 to 15. Intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride compared with oxymetazoline hydrochloride twice daily achieved greater improvement in nasal symptom scores (3.36, 3.29 and 2.44 for mometasone furoate nasal spray and three sprays of oxymetazoline hydrochloride, mometasone furoate nasal spray and 1 spray of oxymetazoline hydrochloride, and oxymetazoline hydrochloride twice daily, respectively; p < 0.002).Reference Meltzer, Bernstein, Prenner, Berger, Shekar and Teper6

Rael et al. noted that the treatment group using intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride reported the highest improvement in nasal congestion scores with a 22 per cent increase in average daily scores at 5 to 7 (nasal congestion score, 1.56; 95 per cent confidence interval (CI), 1.23–1.89), statistically superior to the intranasal corticosteroid spray and placebo group with 1.4 per cent on days 5 to 7 (nasal congestion score, 2.16; 95 per cent CI, 1.94–2.38). These results were based on twice daily diary cards with scores ranging from 0 (asymptomatic) to 3 (most severe).Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7 Thongngarm et al. found that nasal congestion was significantly reduced in patients with chronic rhinitis on days 15 to 28 and 29 to 42 in the intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride group when compared with the placebo group.Reference Thongngarm, Assanasen, Pradubpongsa and Tantilipikorn5

Nasal volume

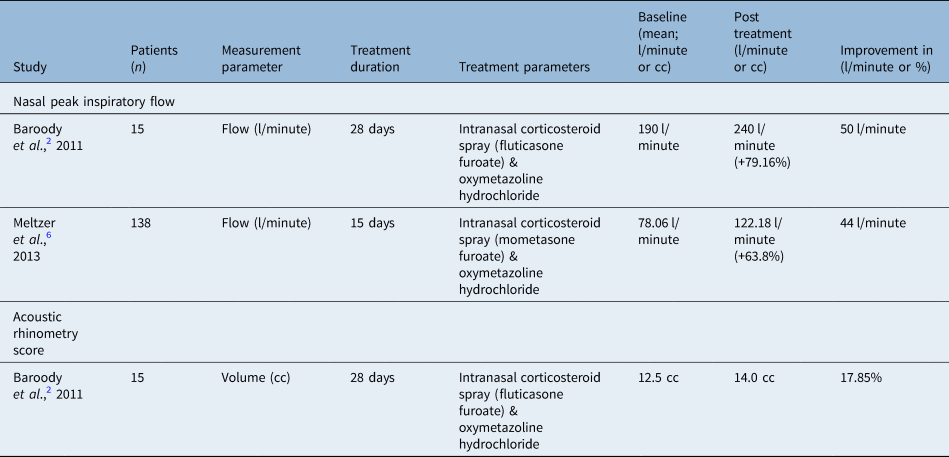

Nasal volume may be quantitatively measured with an acoustic rhinometer. This was performed in 60 patients across one study with an Eccovision® acoustic rhinometer. Results from the study performed by Baroody et al. demonstrated that nasal volume at four weeks post-treatment is greatest in the intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride combination group with less nasal obstruction and significantly higher nasal volume (standard error of the mean 1 (SEM), 15.8 + 1.1 ml; p < 0.03) compared with both placebo (12.1 + 0.9 ml) versus oxymetazoline hydrochloride (12.4 + 0.8 ml) alone.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2

Assessment of nasal volume was also measured by nasal peak inspiratory flow in two studies. Baroody et al. measured nasal peak inspiratory flow, reporting an improvement of 50 l/minute in the intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride group (+79.16 per cent from baseline of 190 l/minute), which was significantly higher than the intranasal corticosteroid spray or oxymetazoline hydrochloride group alone (p = 0.027). Nasal peak inspiratory flow was followed for two weeks after discontinuation of treatment in all arms of the study by Baroody et al. to assess for rebound congestion, which is discussed below.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2 The summary of data on the objective outcomes from acoustic rhinometry and nasal peak inspiratory flow is reported in Table 5.

Table 5. Measured nasal volume

Quality of life

All studies measured quality of life outcomes with the Rhinitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (RQLQ), Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life or Mini Rhinitis Quality of Life Questionnaire, which were completed by the study participants throughout or upon completion of treatment. Amongst the studies, Rael et al. reported a significant difference in sleep improvement for the intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride treatment arm compared with the placebo arm. Sleep improvement increased by 17 per cent on days 6 to 10 and by 28 per cent on days 13 to 20 (p < 0.04).Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7

Rhinitis medicamentosa

In order to assess for rhinitis medicamentosa, or rebound congestion, studies followed patients for a range of 7 to 22 days after completion of treatment. No difference was reported in symptoms amongst treatment groups by any of the studies. After treatment was discontinued in the study by Baroody et al., which objectively measured nasal peak inspiratory flow daily for two weeks following completion, there was no difference when compared with baseline value in nasal peak inspiratory flow for the intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride group to suggest rhinitis medicamentosa occurred. Additionally, patients did not report worsening of nasal congestion symptoms for the two weeks following discontinuation of intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride treatment.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2 Rael et al. maintained use of mometasone furoate for 22 days following discontinuation of oxymetazoline hydrochloride use, and no difference in symptoms was reported after 42 days of observation.Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7 Although Meltzer et al. reported no rebound congestion in their study of 707 randomised patients, they reported it is possible that rebound congestion occurred and was not reported given the limitation that no daily diaries from patients were collected.Reference Meltzer, Bernstein, Prenner, Berger, Shekar and Teper6

Adverse events

The following adverse events were reported: headaches, migraines, cold or virus, sore throat, menstrual cramps, insomnia, lip or tongue numbness, nasal discomfort, epistaxis or bloody secretions, asthma flare-up, swine flu (placebo patient), throat irritation, and feeling jittery. There was no tachyphylaxis reported. A summary of the frequency of these reported adverse events that were reported are listed in Table 5. Meltzer et al. reported a single serious event within an intranasal corticosteroid daily treatment arm and a single serious event within a placebo treatment arm; however, these events were not found to be treatment related.Reference Meltzer, Bernstein, Prenner, Berger, Shekar and Teper6 Additionally, authors from all four studies noted that there was no increase in adverse events in treatment groups when compared with placebo groups. No major adverse events such as myocardial infarction or stroke were found amongst any of the studies. Life threatening adverse events or death did not occur.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2,Reference Thongngarm, Assanasen, Pradubpongsa and Tantilipikorn5–Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7

Discussion

Oxymetazoline hydrochloride 0.05 per cent nasal spray (oxymetazoline hydrochloride) is widely accessible to patients worldwide and available over the counter, making it an easy and reliable self-care option for patients seeking quick relief from nasal congestion. Known for its vasoconstrictive and sympathomimetic properties, oxymetazoline hydrochloride effectively reduces local oedema on nasal mucosa via alpha-adrenergic receptors.Reference Bickford, Shakib and Taverner14 Although oxymetazoline hydrochloride may provide immediate relief for nasal congestion, data suggest that after long-term use, discontinuation of oxymetazoline hydrochloride may lead to worsened mucosal oedema from compensatory vasodilation known as rebound congestion or rhinitis medicamentosa and reduction in efficacy, or tachyphylaxis. Subsequently, this creates a vicious cycle in which patients become increasingly reliant on larger and more frequent doses of oxymetazoline hydrochloride posing a challenge for patients to wean off it while maintaining symptoms of nasal congestion.Reference Graf, Enerdal and Hallén15 For these reasons, patients are typically instructed not to use oxymetazoline hydrochloride for longer than 3 to 14 days.Reference Wallace, Dykewicz, Bernstein, Blessing-Moore, Cox and Khan4,Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7,Reference Bousquet, Lund, van Cauwenberge, Bremard-Oury, Mounedji and Stevens16

The exact mechanism of the development of rhinitis medicamentosa or its frequency of development with prolonged use of oxymetazoline hydrochloride is unknown.Reference Cingi, Ozdoganoglu and Songu17 Patients with a long history of rhinitis medicamentosa develop inflammation within the mucosa such as epithelial and histological changes.Reference Graf, Enerdal and Hallén15 The potential for topical decongestants to cause rhinitis medicamentosa is listed as a side effect in the Physicians’ Desk Reference and prompts limiting usage to twice daily for up to five days.18 The reports addressing this recommendation are conflicting. Graf et al. discovered how benzalkonium chloride, an ingredient included in the oxymetazoline formulary at the time of the study (1999) for its bactericidal and preservative properties, was observed to worsen rhinitis medicamentosa. Notably, benzalkonium chloride has potentially harmful effects on the nasal mucosa from its risk of damage to nasal cilia.Reference Graf, Enerdal and Hallén15 To this day, the preservative is still listed as an inactive ingredient in most oxymetazoline formularies.

In contrast, several other studies have shown lack of rhinitis medicamentosa occurrence when oxymetazoline hydrochloride or xylometazoline has been used for up to eight weeks.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2,Reference Liu, Zhou, Zeng and Luo19 In addition to these observations, the use of intranasal steroids in guinea pigs has been shown to hasten the recovery from rhinitis medicamentosa associated with cessation of topical decongestants.Reference Tas, Yagiz, Yalcin, Uzun, Huseyinova and Adali20 Vaidyanathan et al. demonstrated that healthy human patients who developed rhinitis medicamentosa, primarily mediated by a-adrenoreceptors, could successfully reverse rhinitis medicamentosa with use of intranasal fluticasone propionate.Reference Vaidyanathan, Williamson, Clearie, Khan and Lipworth12 The absence of rebound congestion in the intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride patients in our study was not surprising because of the adjunct dosing of intranasal corticosteroid spray, though we cannot conclude intranasal corticosteroid spray prevented rhinitis medicamentosa from occurring with prolonged oxymetazoline hydrochloride use as explored in other studies.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2,Reference Thongngarm, Assanasen, Pradubpongsa and Tantilipikorn5–Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7

Several studies have investigated the potential risk of tachyphylaxis with long-term use of oxymetazoline hydrochloride for relief of nasal congestion. There are data to support that use of oxymetazoline hydrochloride has not been shown to cause tachyphylaxis until it has been used at least three times daily for four weeks.Reference Watanabe, Foo, Djazaeri, Duncombe, Mackay and Durham21,Reference Yoo, Seikaly and Calhoun22 This was also demonstrated in two separate studies by Graff et al. and Vaidyanathan et al., in which intranasal corticosteroid spray was primarily used to demonstrate that rhinitis medicamentosa caused by long-term oxymetazoline hydrochloride use was secondary to oedema rather than vasodilation. These studies also demonstrated improvement in rebound congestion after a two-week treatment of intranasal corticosteroid spray therapy alone following prolonged oxymetazoline hydrochloride use and subsequent cessation because of rhinitis medicamentosa.Reference Vaidyanathan, Williamson, Clearie, Khan and Lipworth12,Reference Graf, Enerdal and Hallén15

The results from our systematic review demonstrated that in oxymetazoline hydrochloride naïve patients, initiating combination treatment with intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride may not only serve as a treatment option for rhinitis medicamentosa but also provide superior relief in nasal congestion symptoms when compared with the use of either agent alone. This was demonstrated by objective and subjective data points.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2,Reference Thongngarm, Assanasen, Pradubpongsa and Tantilipikorn5–Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7 Objective data to indirectly and directly measure nasal volume included nasal peak inspiratory flow and acoustic rhinometry.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2,Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7

Peak nasal inspiratory flow measures nasal potency indirectly by measuring airflow in a relatively rapid and inexpensive way. In a study by Fuller et al., the authors found nasal peak inspiratory flow to be a useful means for measuring outcomes post-septorhinoplasty. Although the authors acknowledge nasal peak inspiratory flow is not intended for diagnostic purposes, their study has been the largest to assess the relationship between nasal peak inspiratory flow with Nasal Obstruction and Septoplasty Effectiveness Scale scores and demographic data comprising 610 patients with mean age of 36.12 years, similar to the mean ages across the 4 studies in our review.Reference Fuller, Gadkaree, Levesque and Lindsay23 Meltzer et al. demonstrated a 65.8 per cent increase in nasal peak inspiratory flow (l/minute) in the intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride 3 spray group when compared with the intranasal corticosteroid spray group (40.9 per cent increase) and placebo group (23.2 per cent increase) alone (p < 0.05).Reference Meltzer, Orgel, Bronsky, Furukawa, Grossman and LaForce1

Acoustic rhinometry, developed in the 1970s, measures a cross-sectional area of the internal nose by detecting reflected sound waves; it is reportedly more reliable for measuring the anterior 6 cm of the nasal cavity.Reference Bickford, Shakib and Taverner14 Baroody et al. demonstrated larger nasal volumes through acoustic rhinometry (mean + SEM, 15.8 + 1.1 ml) in the intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride group compared with placebo (mean + SEM, 12.1 + 0.9 ml) or oxymetazoline hydrochloride (mean + SEM, 12.4 + 0.8 ml) groups alone (p < 0.03).Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2 Overall, the included studies did not show differences amongst quality of life data obtained across these treatment groups when compared with placebo groups. However, Rael et al. found improvement in sleep in the intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride cohort compared with the intranasal corticosteroid spray placebo group. Theoretically, this could be explained from increased nasal airflow secondary to decreased oedema, especially since dosing of intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride was administered in the evening in their study.Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7

All four studies reported improvement in nasal symptoms in the combination treatment groups as compared with monotherapy or placebo groups. We recognise the limitations in that each study utilised different methods for collecting symptom scores, and grading symptoms is highly subjective. We also recognise the possibility of patient bias. Perhaps one of the more clinically relevant findings was that no rebound congestion was reported in the 336 patients treated with dual therapy of prolonged oxymetazoline hydrochloride use after patients were followed for up to 22 days of observation.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2,Reference Thongngarm, Assanasen, Pradubpongsa and Tantilipikorn5–Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7

Three of the four studies implemented treatment on patients with verified allergic or non-allergic rhinitis symptoms by performing skin prick testing prior to initiating treatment.Reference Thongngarm, Assanasen, Pradubpongsa and Tantilipikorn5–Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7 In the study by Rael et al., it was explicitly stated that patients on immunotherapy were stabilised for 30 days prior to enrolling in the study. The impact of immunotherapy and other adjunctive treatment such as oral antihistamines was not stratified in these studies.Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7

Because of heterogeneity across studies and lack of sub-analyses available, we were unable to perform analyses on whether or not patients across all studies with allergic rhinitis experienced greater benefit than patients with non-allergic rhinitis. Thongngarm et al. found that patients with allergic rhinitis experienced significant reduction in nasal congestion with intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride on days 4 to 7, 8 to 14, 15 to 28 and 29 to 42 when compared with placebo groups. Their analysis demonstrated a significant improvement in allergic rhinitis patients compared with non-allergic rhinitis patients (allergic patients, n = 18 and non-allergic patients, n = 7; p < 0.05).Reference Thongngarm, Assanasen, Pradubpongsa and Tantilipikorn5 However, this data is limited by the small sample size of 25 patients. Comparing the response of allergic rhinitis to non-allergic rhinitis patients in a larger trial is worthy of further exploration with potential for application to clinical practice.

Given the subjective improvement across all four studies in patients with both allergic and non-allergic rhinitis with no reports of life threatening adverse effects, tachyphylaxis or rebound congestion, we propose that the combination of oxymetazoline hydrochloride and intranasal corticosteroid spray may be considered for use as a treatment option for patients entering a season triggering severe allergic rhinitis symptoms as they seek extra relief when symptoms are not controlled with intranasal corticosteroid spray alone.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2,Reference Thongngarm, Assanasen, Pradubpongsa and Tantilipikorn5–Reference Rael, Ramey and Lockey7 Recent literature on the combination treatment of intranasal corticosteroid spray with inhaled antihistamine has encouraged the practice of combining intranasal spray modalities for targeting different receptor pathways and the release of the first FDA approved intranasal formulation of its kind: Dymista® (azelastine hydrochloride antihistamine and fluticasone intranasal steroid).Reference Debbaneh, Bareiss, Wise and McCoul24,Reference Ratner, Hampel, Van Bavel, Amar, Daftary and Wheeler25 Currently, there are no published studies comparing the use of intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride to intranasal corticosteroid spray and inhaled antihistamine, or a treatment course utilising a combination of oxymetazoline hydrochloride with both intranasal corticosteroid spray and inhaled antihistamine.

The theory of combining intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride to synergistically target nasal mucosa receptors may be especially beneficial for patients presenting with moderate to severe nasal congestion or facing seasonal changes that cause an exacerbation of allergic rhinitis symptoms. Because oxymetazoline hydrochloride can provide prompt decongestive properties to the nasal mucosa, it may allow for increased nasal volume and surface area for the intranasal corticosteroid to effectively target the nasal mucosa.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2,Reference Meltzer, Bernstein, Prenner, Berger, Shekar and Teper6,Reference Vaidyanathan, Williamson, Clearie, Khan and Lipworth12,Reference Eskiizmir, Hircin, Ozyurt and Unlu26 Although the effects of intranasal steroids can be observed as early as 12 hours after administration, the maximum efficacy may take as long as 12 weeks.Reference Bridgeman27,Reference Penttilä, Poulsen, Hollingworth and Holmström28 The delay in maximal effect often prevents patients from instant gratification from the benefit of intranasal corticosteroids.Reference Penttilä, Poulsen, Hollingworth and Holmström28 Meanwhile, oxymetazoline hydrochloride is a non-selective alpha adrenergic agonist, which leads to vasoconstriction of nasal vessels resulting in decreased oedema and prompt relief of nasal congestion with a nearly instantaneous onset of action within 5 to 10 minutes and resulting in increased diameter and airflow.Reference Baroody, Brown, Gavanescu, DeTineo and Naclerio2

Theoretically, for patients with suboptimal response to intranasal corticosteroid spray and inhaled antihistamine therapy, the addition of oxymetazoline hydrochloride at the onset of treatment could be beneficial. However, further research on dual therapy oxymetazoline hydrochloride with either intranasal corticosteroid spray or intranasal antihistamine versus monotherapy is needed. There is potential for the role of oxymetazoline hydrochloride in providing relief for patients with seasonal allergy exacerbations, upper respiratory infections or severe allergic reactions refractory to monotherapy nasal spray, and further studies such as randomised controlled trials are recommended. Our study demonstrated that the combination of intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride has beneficial effects beyond those of intranasal corticosteroid spray alone.

In the authors’ opinion, the selection of which intranasal spray combination would be a better fit to a patient depends on the clinical condition. For example, combination oxymetazoline hydrochloride and intranasal corticosteroid spray would be a better fit for a patient suffering from non-allergic rhinitis, whereas other options will better suit a patient with allergic rhinitis. These are considerations recommended by the authors.

We acknowledge several limitations in our review. Unfortunately, the studies included are short term, which fail to evaluate long-term outcomes or any potential long-term adverse effects. Therefore, caution is needed when choosing to commence a patient on oxymetazoline hydrochloride as the risk of rhinitis medicamentosa with continued use cannot be addressed with the current data. The data amongst the studies were heterogenous, and therefore we were unable to perform a meta-analysis. Control groups across studies varied, which also limited our ability to compare studies (i.e. combinations of intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride and placebo groups as referenced in Table 1). Studies also varied in follow up time from 7 to 22 days as well as follow up questioning and reporting of symptoms. Nasal congestion is arguably subjective in nature and variable throughout the day, and although we acknowledge the objective measurements in two studies, these tests may be variable and user dependent. Quality of life scores may be dependent on time of day and associated with timing of medication administration. The adjunct of oral antihistamines and other modalities such as immunotherapy may serve as confounding variables in the individual studies. Not all studies discussed adjunctive treatment as exclusion criteria.

Conclusion

Current international literature demonstrates that intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride combination treatment has shown superiority in reducing rhinitis symptoms when compared with use of either intranasal corticosteroid spray or oxymetazoline hydrochloride alone without inducing rhinitis medicamentosa. Further research is warranted to determine if the risk for developing rhinitis medicamentosa may be significantly reduced when intranasal corticosteroid spray is offered to patients early in the treatment course of oxymetazoline hydrochloride use and initiated prior to abrupt cessation of oxymetazoline hydrochloride. Continuation of intranasal corticosteroid spray after withdrawal of oxymetazoline hydrochloride was not linked to any adverse events in patients observed up to 22 days. The long-term risks of intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride combination treatment are still unknown and further research is recommended for the use of intranasal corticosteroid spray and oxymetazoline hydrochloride in long-term management of chronic rhinitis and allergic rhinitis symptoms, in addition to its role for the treatment of rhinitis medicamentosa.

Competing interests

None declared