Introduction

The use of cautery is well established for the treatment of epistaxis, with a wealth of literature discussing the merits of cautery and its use within acute epistaxis management protocols.Reference Key 1 – Reference Barnes, Spielmann and White 3 There is also extensive literature describing various nasal cautery technical tips, to aid visualisation of bleeding sites,Reference Badran and Arya 4 , Reference Bray 5 to provide easier access to bleeding points,Reference Alderson 6 – Reference Judd 9 and to minimise complications such as skin staining with silver nitrate.Reference Maitra and Gupta 10

Despite this, no clear evidence-based guidelines exist relating to the appropriate indications for, or efficacy of, specific cautery techniques used in the management of adult patients presenting with epistaxis. Current clinical practice is mostly based on personal experience, prior training and equipment availability, without any clear evidence base, and with a lack of standardisation of care and significant variability in practice.

The two principal methods of nasal cautery used are chemical cautery and electrocautery. The types of electrocautery available are variable, but include monopolar and bipolar diathermy. Silver nitrate sticks are the most common form of chemical cautery used in the UK. Nasal cautery is often considered to be preferable to nasal packing in light of patient benefits, which include reduced morbidity and discomfort, and health economic benefits, including the potential avoidance of hospital admission.Reference Nikolaou, Holzmann and Soyka 11 However, a short review of the literature published in 1999 found a lack of studies directly comparing the interventions.Reference Mackway-Jones 12 Electrocautery is often considered to be superior to chemical cautery, although the evidence base for this in adults has not been clearly established.Reference Toner and Walby 13

Aims

This review aimed to address the following key clinical questions that were identified relating to intranasal cautery: what are the failure rates of chemical cautery and electrocautery?; when should intranasal cautery be attempted?; which methods of intranasal cautery should be endorsed as optimum treatment on the balance of benefits, risks, patient tolerance and economic assessment?; who should perform intranasal cautery?; and does the use of pharmaceutical adjuncts or visual enhancement during cautery affect epistaxis control?.

Materials and methods

This work forms part of a set of systematic reviews designed to summarise the literature prior to the generation of a UK national management guideline for epistaxis. This review addresses a single research domain: intranasal cautery. A common methodology has been used in all the reviews, described in the first of the publications.Reference Khan, Conroy, Ubayasiri, Constable, Smith and Williams 14 Studies were only included if they primarily included patients aged 16 years and above treated for epistaxis within a hospital environment. The search strategy can be found in the online supplementary material that accompanies this issue.

Results

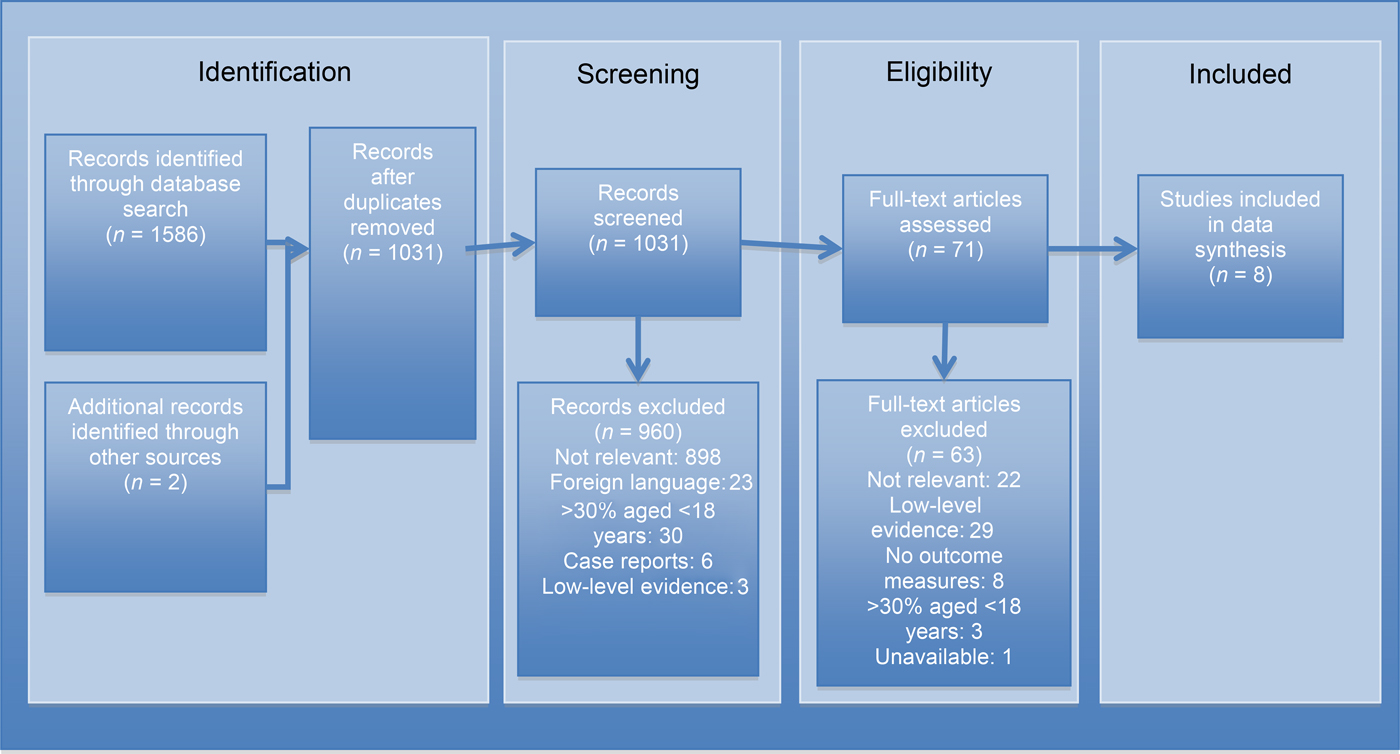

Eight studies were included for analysis in the cautery review.Reference Nikolaou, Holzmann and Soyka 11 , Reference Toner and Walby 13 , Reference Soyka, Nikolaou, Rufibach and Holzmann 15 – Reference Mattoo, Yousuf, Mir, Muzaffar and Pampori 20 Figure 1 illustrates the search and article selection process. A summary table (Appendix I) provides details from each of the included studies. Five studies, including one randomised controlled trial, compared the failure rates of either chemical cautery, electrocautery or packing,Reference Toner and Walby 13 , Reference Soyka, Nikolaou, Rufibach and Holzmann 15 – Reference Shargorodsky, Bleier, Holbrook, Cohen, Busaba and Metson 18 as summarised in Table I. Two studies were identified that included data on treatment costs, as shown in Table II.Reference Nikolaou, Holzmann and Soyka 11 , Reference Henderson, Larkins and Repanos 16 One study included a comparison of patient discomfort for different treatment methods.Reference Nikolaou, Holzmann and Soyka 11 One study investigated the benefits of using an operating microscope to aid cautery,Reference Nicolaides, Gray and Pfleiderer 19 and one assessed the failure rates of cautery using different topical pharmaceutical agents prior to cautery.Reference Mattoo, Yousuf, Mir, Muzaffar and Pampori 20

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) diagram for the cautery review, mapping the number of records identified, included and excluded during different review phases.

Table I Comparison of chemical cautery, electrocautery and packing failure rates

N/A = not applicable

Table II Treatment cost comparison

CHF = Switzerland Francs

Summary of evidence

Chemical cautery versus electrocautery

Three studies specifically compared chemical cautery and electrocautery (Table I). Toner and Walby performed a study on 119 adult patients, and compared the effectiveness of hot wire cautery with silver nitrate cautery.Reference Toner and Walby 13 Cautery was performed after a mixture of 4 per cent lignocaine and 1:1000 adrenaline was applied to the nasal mucosa on wool pledgets. At a two-month follow-up appointment, the recurrence rate, severity and other complications were measured. Of the initial 119 patients treated, only 97 attended follow up and were included in data analysis. The high rate of loss to follow up (18.5 per cent) may have led to the overestimation of epistaxis failure rates in both cautery groups. The study concluded that there was no significant difference between the two cautery methods in patients with recurrent epistaxis (p = 0.09). However, group sizes were relatively small and unbalanced (hot wire, n = 43; chemical cautery, n = 54), and the power calculation performed was based on a predicted chemical cautery success rate of 50 per cent, when the study found that it was actually 70 per cent. This may have led to the study being too underpowered to identify any difference in outcome.

Soyka et al. used data from a larger prospective study to investigate the effects of aspirin on epistaxis.Reference Soyka, Nikolaou, Rufibach and Holzmann 15 It included 397 patients treated with bipolar cautery and 73 treated with silver nitrate cautery. Patients were managed according to the preferences of the treating doctor, and no details were provided regarding the nasal preparation or cautery methods used. Immediate failure was defined as further bleeding within 24 hours of treatment, and recurrence as re-bleeding within 4 weeks of treatment. Fisher's exact test revealed significantly lower immediate failure rates with the use of bipolar cautery when compared to chemical cautery (p = 0.04). Ninety per cent of individuals treated with electrocautery were recurrence-free at 12 days using Kaplan–Meier analysis, compared to 90 per cent at 3 days using chemical cautery.

Henderson et al. compared the treatment failure rates before and after implementation of a treatment protocol which recommended the use of bipolar cautery when previously chemical cautery was used.Reference Henderson, Larkins and Repanos 16 Treatment failure was defined as the need for immediate nasal packing. Sixty-three patients were treated with chemical cautery prior to the introduction of electrocautery, and 61 patients were treated with electrocautery after. The study identified a significant reduction in failure and therefore admission rates (p < 0.01). However, the use of bipolar cautery was part of a new treatment protocol; therefore, electrocautery effectiveness may have been overestimated via other protocol changes and the possibility of improved training.

Although the types of electrocautery used and precise definitions of treatment failure varied between studies, it was determined that they were similar enough to pool the data for further analysis. Thus, 830 patients’ data were pooled from the 3 studies. The weighted mean failure rate was 14.5 per cent for electrocautery and 35.1 per cent for chemical cautery. Analysis using a chi-square test revealed a significantly lower failure rate for electrocautery when compared to chemical cautery (p < 0.01, χ2 = 133.0).

Cautery versus nasal packing

Two articles compared forms of cautery to nasal packing (Table I). Ando et al. primarily investigated the risk factors for recurrent epistaxis, with a focus on the initial treatment.Reference Ando, Iimura, Arai, Arai, Komori and Tsuyumu 17 This retrospective study included 101 patients with active posterior bleeding. There was a significantly lower recurrence rate (p = 0.04) when patients underwent electrocautery (6.4 per cent) compared to packing (40.7 per cent).

Shargorodsky et al. conducted a retrospective study of 147 adult patients who either received silver nitrate cautery or nasal packing (comprising different forms of non-dissolvable packing).Reference Shargorodsky, Bleier, Holbrook, Cohen, Busaba and Metson 18 Treatment failure was defined as recurrence requiring intervention within 7 days or the immediate failure to control bleeding. Significantly lower failure rates (p = 0.01) occurred following treatment with chemical cautery (24 per cent) when compared to nasal packing (57 per cent).

Both studies had significant potential selection bias, with some patients in whom cautery had failed subsequently going on to be packed. Therefore, although packing was associated with higher rates of recurrence, this was likely related to the type of bleed that requires packing (e.g. posterior or heavy bleeding, or associated with anticoagulation), rather than packing directly causing an increased recurrence risk. A comparison of failure rates between the studies is shown in Table I.

Impact of cautery on admissions, costs and hospital stay

Henderson et al., in addition to assessing the failure rates of electrocautery and chemical cautery (as shown in Table I), also investigated the admission rates and costs associated with the techniques.Reference Henderson, Larkins and Repanos 16 Analysis was performed following the introduction of a new protocol that included electrocautery (as discussed above). Admission rates decreased significantly (p < 0.01) from 62 per cent to 37 per cent, with associated savings calculated at £117 per patient.

Similar cost savings were identified by Nikolaou et al., who performed a prospective study to investigate the treatment costs of chemical cautery, bipolar cautery and Rapid Rhino® packing.Reference Nikolaou, Holzmann and Soyka 11 The study, performed in Switzerland, included a cost analysis conducted on 96 patients. Based on a currency exchange from Swiss francs to British pounds accurate at the time of the study, the authors reported savings of approximately £106 per patient treated with bipolar cautery when compared to Rapid Rhino packing (p < 0.01). These findings are summarised in Table II.

However, the method of cost calculations used lacked detail in both studies, which created potentially significant bias, limiting their reliability. Furthermore, none of the included studies assessed the optimum use of cautery or patients’ tolerance of the procedures.

Patient tolerance

Nikolaou et al. collected visual analogue scale (VAS) scores investigating patient discomfort following epistaxis treatment from 84 participants.Reference Nikolaou, Holzmann and Soyka 11 The median VAS score was 2.0 for bipolar cautery, 1.5 for chemical cautery and 6.0 for Rapid Rhino insertion. There was no significant difference identified between cautery methods (p = 0.7), but packing was found to be significantly more painful than cautery (p < 0.01). Although there were clear differences between the packing and cautery groups, the relatively small sample size for comparison between the chemical (n = 14) and bipolar (n = 40) cautery groups may have increased the chance of a type II error.

Appropriate practitioners

There were no studies identified that investigated differences in success rates or complications between the grade, level of training, or type of healthcare professional performing cautery.

Adjuncts to cautery

Multiple studies were initially identified within the literature search that investigated the success rates of posterior epistaxis treatment using either microscopy or nasoendoscopy. However, as most of these were case series, they were excluded from further analysis. Nicolaides et al. compared the effectiveness of hot wire cautery performed with an operating microscope to that of conventional treatment without a microscope.Reference Nicolaides, Gray and Pfleiderer 19 Using a microscope improved localisation of the bleeding point (82 per cent vs 57 per cent), improved the arrest of bleeding (82 per cent vs 23 per cent), and significantly reduced the rate of nasal packing (p < 0.001) and the length of hospital stay (p < 0.001). However, the retrospectively analysed control group included patients treated immediately before the introduction of the new technique, with some treated with silver nitrate, a potential confounding factor. Hence, no conclusions could be drawn regarding the use of visualisation adjuncts to aid epistaxis treatment.

Mattoo et al. assessed the effect of applying xylometazoline- or adrenaline-soaked cotton packs for 30 minutes prior to attempting silver nitrate cautery, and compared this to pinching of the nose for 10 minutes.Reference Mattoo, Yousuf, Mir, Muzaffar and Pampori 20 The success rate of cautery was measured by the immediate achievement of haemostasis and the absence of recurrence within 4 days. There was a statistically significant improvement in success rates when comparing nasal pinching with xylometazoline (p = 0.01), and nasal pinching with adrenaline (p = 0.001). There was no significant difference between the use of xylometazoline and adrenaline.

Limitations

The full text of one article was unavailable and therefore could not be included for eligibility assessment. This paper was published almost 30 years ago, and assessed hot wire cautery, which is rarely used in modern practice. The other studies had considerable heterogeneity in their designs and methodology, which limited pooling of data. Additionally, many studies did not randomise treatment and were often evaluations of new treatment protocols, which introduced further potential bias, as they may have included other recommendations and improved the training of treating doctors. As discussed earlier, there is a risk of selection bias, particularly when comparing those patients treated with packing and cautery in non-randomised studies, as there may be other factors influencing failure or recurrence rates, such as bleeding severity or use of anticoagulants.

Conclusion

There is evidence to suggest that forms of electrocautery (bipolar was the most commonly used) are more effective at treating active epistaxis than chemical cautery. Additionally, limited evidence suggests that electrocautery is not associated with higher complication rates or patient discomfort. There is limited low-quality evidence to suggest that the use of electrocautery reduces the length of hospital stay and treatment costs. In addition, packing is associated with a higher risk of recurrence when compared to any form of cautery, though this finding does not account for possible differences in bleeding severity or location between intervention groups. The application of a topical vasoconstrictor may improve the success rates of cautery. No high-quality studies were identified that compared the effectiveness of adjuncts to epistaxis control, such as the use of a microscope or nasoendoscope.

Future studies in this area should include randomised controlled trials that assess the need for nasal packing when bipolar or chemical cautery are used as a primary treatment, and an analysis of the costs associated with each treatment and treatment failure. Future studies should assess the value of nasal examination and cautery following pack removal (in those who require packing) prior to discharge from hospital.

Acknowledgement

This review was part of an epistaxis management evidence appraisal and guideline development process funded by ENT-UK. The funding body had no influence over content.

Appendix I Summary of studies included in cautery review