Introduction

The aetiology of Ménière's disease is diverse, and several theories have been postulated. Historically, an accumulation of excess endolymphatic fluid in the inner ear (endolymphatic hydrops) due to impaired resorption has been proposed.Reference Schuknecht1 More recently, a decrease in the number of type II vestibular hair cells in Ménière's disease patients has been demonstrated.Reference Tsuji, Velazquez-Villasenor, Rauch, Glynn, Wall and Merchant2 Patients with Ménière's disease have raised levels of immunoglobulin (Ig) M and the C1q component of complement, and reduced levels of IgA.Reference Evans, Baldwin, Bainbridge and Morrison3 Researchers have also reported: the presence of autoantibodies to an inner ear antigen in a proportion of Ménière's disease patients,Reference Riente, Bongiorni, Nacci, Migliorini, Segnini and Delle Sedie4 increased serum expression of some human leukocyte antigens (B7, A3, DR2 and Cw7),Reference Bernstein, Shanahan and Schaffer5 and a response to steroid therapy in some patients; all these findings are suggestive of an immune aetiology of the disease. Mutations of the COCH gene have also been shown to be associated with Ménière's disease.Reference Fransen, Verstreken, Verhagen, Wuyts, Huygen and D'Haese6

Symptom management is multifactorial, and includes strategies designed to decrease the pressure within the endolymphatic compartment.Reference Furstenberg, Lashmet and Lathrop7 However, despite the existence of several medical and surgical therapies, the optimum treatment for Ménière's disease has yet to be elucidated fully.

Changes in ambient pressure can induce vertigo in divers and pilots, and this effect has been studied using an external pressure chamber; such a chamber has also been observed to control Ménière's disease patients’ symptoms, presumably by displacing endolymph.8, Reference Densert, Densert, Arlinger, Sass and Odkvist9 Similarly, local application of overpressure from a low intensity alternating pressure generator has been shown experimentally to induce remission in five patients with debilitating Ménière's disease.Reference Densert and Densert10

The Meniett® device (Medtronic Xomed, Jacksonville, Florida, USA), a small, portable device costing £1950, is thought to work in a similar manner (Figure 1).8 This device administers computer-controlled, low pressure (range 0 to 20 cm H2O), 6 Hz, 0.6 second air pulses to the middle ear via a polyethylene tube connected to an earpiece which forms a seal in the ear canal. Trans-tympanic air transmission is possible through prior insertion of a grommet. Treatment cycles last 5 minutes, and comprise three 60 second cycles of pressure and three 40 second cycles of rest. It is believed that these low-pressure pulses stimulate the flow of endolymphatic fluid, thereby displacing excess inner ear endolymph to equalise pressure within the inner ear and relieve the symptoms of Ménière's disease. In a randomised, placebo-controlled study of patients undergoing treatment with the Meniett® device, electrocochleographic measurements recorded immediately following intervention demonstrated a statistical difference in the ratio of summating potential to action potential of the electrocochleographic response complex in the treatment group, compared with the control group; this provided objective evidence of an improvement in inner ear physiology due to the Meniett® device.Reference Densert, Densert, Arlinger, Sass and Odkvist9

Fig. 1 The Meniett® device. (Picture reprinted courtesy of Xomed®.)

The Meniett® device was first licensed for use in the treatment of Ménière's disease in Europe in 1997, but is not yet widely used in the UK. There are as yet no published studies describing its application in this country.

Our departments have previously published a study of patients’ perceptions of intra-tympanic gentamicin in the treatment of Ménière's disease.Reference Smith, Sandooram and Prinsley11 The current study used a similar design, and was undertaken as follow up to our prior study. The current study used validated questionnaires to assess the experiences of patients treated with the Meniett® device, who had initially failed lifestyle and traditional medical managementReference Furstenberg, Lashmet and Lathrop7 of Ménière's disease; the study also compared results with our previous, similar series of patients receiving intra-tympanic gentamicin therapy.Reference Smith, Sandooram and Prinsley11

Materials and methods

We undertook a retrospective, questionnaire-based survey and analysis of medical records for patients who had undergone treatment with the Meniett® device over a four to six week period at a university teaching hospital or a district general hospital.

A diagnosis of definite Ménière's disease was based on the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery guidelines: i.e. the patient had two or more attacks of vertigo (each of at least 20 minutes’ duration), documented hearing loss on pure tone audiography on at least one occasion, and tinnitus or aural fullness on the affected side, and other possible causes were excluded.Reference Monsell, Balkany, Gates, Goldenberg, Meyerhoff and House12 Magnetic resonance imaging excluded a cerebello-pontine angle lesion.

Patients were initially given treatments as outlined in Table I. If symptoms of troublesome vertigo were still present after six months, they were offered the Meniett® device. A Shah grommet was inserted into the tympanic membrane of the affected ear, and the device was loaned to the patient a few weeks later, to be used for three 5 minute cycles per day, for four to six weeks. Before using the device, patients were instructed to perform a Valsalva manoeuvre to ensure patency of the grommet. Patients with active middle-ear disease were not offered a grommet and the Meniett® device until the inflammation had been eliminated; neither were patients with Ménière's disease in the better hearing ear. Patients treated with the Meniett® device were told to abstain from any other Ménière's disease treatments.

Table I Patients’ previous medical treatment

Pts = patients

Consecutive patients who used the Meniett® device from August 2004 to August 2008 were eligible for inclusion in the study. These patients were sent a covering letter inviting them to participate, and emphasising that their future care would not be affected by their responses. Patients were also sent two questionnaires – the Vertigo Symptom ScaleReference Yardley, Masson, Verschuur, Haacke and Luxon13 and the Glasgow Benefit InventoryReference Robinson, Gatehouse and Browning14 – which enquired about changes in their symptoms as a result of using the Meniett® device. Patients’ responses were anonymised.

The Vertigo Symptom Scale questionnaire enquires about the severity and type of vertigo symptoms. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 (i.e. not at all) to 4 (i.e. several times per day) to indicate the frequency of symptoms in an average month following treatment.

The Glasgow Benefit Inventory consists of 18 questions which assess the effect of an intervention (in this case, the Meniett® device) on the patient's quality of life and health status. Question responses are based on a five-point Likert scale which ranges from a large deterioration through to a large improvement in health status. Glasgow Benefit Inventory results are converted into a total score based on the 18 questions, and also into three subscales scores – a general subscale (12 questions), a social support subscale (three questions) and a physical health subscale (three questions). All scores range from −100 to +100, where −100 represents a large deterioration, +100 a large improvement, and 0 no change in quality of life.

In addition, patients were asked whether they thought the Meniett® device had affected their symptoms, and, if so, how long it took them to notice any symptom changes.

The Vertigo Symptom Scale and Glasgow Benefit Inventory scores were compared for patients in the current study (treated with the Meniett® device) versus 23 patients in our departments’ previous study (treated with intra-tympanic gentamicin).Reference Smith, Sandooram and Prinsley11 Comparison was also made with questionnaire scores for alternative Ménière's disease interventions, and for other otorhinolaryngological procedures.

Patients’ responses were anonymised so that their future care could not be influenced.

Results

Between August 2004 and August 2008, the Meniett® device was used by 33 patients, with a male to female ratio of 1.0 to 2.7 and an age range of 31 to 83 years (mean 55.5 years). Thirty patients returned the questionnaires, a response rate of 90.9 per cent. Table I demonstrates the variety of treatments patients had already received; in the majority of cases, more than one treatment modality had been tried.

Nineteen of the 30 respondents felt that the Meniett® device had improved their symptoms of vertigo and hearing; this improvement had usually occurred immediately or within a few days of commencing treatment. The longest time to improvement was one month, reported by two patients. Of these 19 patients, five considered their hearing to be better as a result of the Meniett® device. The remaining 11 patients reported no change in vertigo or tinnitus despite using the Meniett® device. Four patients deemed the device so useful that they either borrowed it for further periods of use, or bought their own.

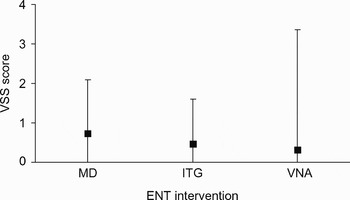

Figure 2 shows patients’ reported Vertigo Symptom Scale scores for the Meniett® device, which ranged from 0 to 4, compared with scores for other recognised forms of Ménière's disease treatment (i.e. intra-tympanic gentamicin and vestibular nerve ablation).Reference Smith, Sandooram and Prinsley11 Although the Vertigo Symptom Scale score range was slightly higher for the Meniett® device, compared with the other two treatments, its results were still very favourable in terms of reducing vertigo attacks.

Fig. 2 Comparison of mean (black square) and range (whiskers) of Vertigo Symptom Scale (VSS) scores for the Meniett® device (MD), compared with other Ménière's disease interventions (intra-tympanic gentamicin (ITG) and vestibular nerve ablation (VNA).Reference Smith, Sandooram and Prinsley11

Figure 3 shows mean Glasgow Benefit Inventory scores for the benefit of the Meniett® device and of intra-tympanic gentamicinReference Smith, Sandooram and Prinsley11 for Ménière's disease treatment, compared with scores for the benefit of other treatments for other otorhinolaryngological conditions (i.e. cochlear implantation, rhinoplasty and tonsillectomy).Reference Robinson, Gatehouse and Browning14 The mean Glasgow Benefit Inventory general subscale score for the Meniett® device was comparable to that of intra-tympanic gentamicin, whereas the mean social support and physical health subscale scores were more comparable to those for cochlear implantation and rhinoplasty.

Fig. 3 Mean Glasgow Benefit Inventory (GBI) subscale scores for the benefit of the Meniett® device (MD) and intra-tympanic gentamicin (ITG) in the treatment of Ménière's disease, compared with the benefit of other treatments for other otorhinolaryngological conditions (cochlear implantation (CI), rhinoplasty (R) and tonsillectomy (T)).Reference Smith, Sandooram and Prinsley11, Reference Robinson, Gatehouse and Browning14

Discussion

Ménière's disease is a cyclical and unpredictable condition, and it is stated that two-thirds of patients will improve without treatment.Reference Torok15 Although the precise cause of Ménière's disease remains unknown, changes in ambient pressure are known to be associated with an improvement in symptoms. This effect is exploited by the Meniett® device, which produces intermittent changes in pressure transmitted via the round window membrane to the perilymph, thereby compressing the endolymph and re-distributing labyrinthine pressure. It is thought that such pressure changes reduce endolymphatic fluid volume by promoting outflow into the endolymphatic sac.Reference Densert, Densert, Arlinger, Sass and Odkvist9 It has also been postulated that pressure changes may trigger reflexes which affect endolymph productionReference Sakikawa and Kimura16 and atrial natriuretic peptide production from the endolymphatic sac.Reference Dornhoffer, Danner, Zhou and Li17

Medical interventions for Ménière's disease can be effective; however, a Cochrane reviewReference James and Burton18 found no evidence that medical treatment with betahistine conferred any benefit on symptoms, compared with placebo. We have previously shown that weekly intra-tympanic injections of 40 mg gentamicin can potentially cause a greater than 10 dB hearing loss in up to 33 per cent of patients, with the potential for a ‘dead ear’.Reference Smith, Sandooram and Prinsley11 In that study, patients were reviewed weekly, and residual vestibular function identified by iced water caloric irrigation. If cold water precipitated nystagmus or vertigo, and if there was no deterioration in the pure tone audiogram, a further 40 mg gentamicin were injected. Most patients required just one injection, but one required five. However, another study which used up to three interval doses of just 12 mg gentamicin within 15 days showed no deleterious effect on hearing.Reference Lange, Maurer and Mann19 A retrospective study of patients with unilateral Ménière's disease who received several intratympanic dexamethasone injections demonstrated acceptable vertigo control in 91 per cent of patients, although dosages and hearing effects were not documented.Reference Boleas-Aguirre, Lin, Della Santina, Minor and Carey20 Surgical treatment of Ménière's disease via vestibular neurectomy is associated with a 40 per cent risk of hearing loss despite a 94 per cent rate of vertigo control;Reference Silverstein, Norrell and Rosenberg21 however, saccus decompression leads to a vertigo control rate of 80 per cent, with less risk to hearing.Reference Snow and Kimmelman22

The current study was performed to assess the quality of life of patients with Ménière's disease who received treatment with the Meniett® device. This is the first study to examine usage of the Meniett® device in the UK. Our findings indicate that the Meniett® device constitutes a simple, minimally invasive and effective method of treating Ménière's disease. When specifically asked, 19 of the 30 patients who responded felt that the device had improved their symptoms of vertigo and tinnitus. The mean Vertigo Symptom Scale score following treatment was 0.7 out of 4, which compares favourably with other Ménière's disease interventions. The mean Glasgow Benefit Inventory general subscale score was higher than that for intra-tympanic gentamicin treatment of Ménière's disease, but Meniett® treatment social support and physical health subscale scores were less than those for intra-tympanic gentamicin, and were similar to those for cochlear implantation and rhinoplasty.

The current study had some limitations worthy of mention.

The number of patients in the series was small; however, this reflected the incidence of Ménière's disease in the population served by the two hospitals.

The treatment period was short, and was restricted by the four to six week loan period for the Meniett® device. Subsequent follow up was also short, but we were interested only in initial symptom control within the first month, as stipulated by the Vertigo Symptom Scale questionnaire. The majority of patients who benefited from the Meniett® device did so within the first few days, and a minority became so reliant on the device that they bought their own.

This study intentionally made no objective assessment of hearing after intervention, as it was a subjective quality of life study designed to examine symptom control. However, five of the 19 patients who felt they had benefited from the Meniett® device considered their hearing to have improved.

The Glasgow Benefit Inventory and Vertigo Symptom Scale scores measured in this study, which indicated the effect of the Meniett® device, were not controlled by a comparison with pre-treatment scores. This was in line with our departments’ previous study, which compared post-gentamicin treatment effects with other validated studies.Reference Smith, Sandooram and Prinsley11 Not all patients who received intra-tympanic gentamicin in that study proceeded to treatment with the Meniett® device, so it is difficult to make a direct comparison between the post-treatment scores of these two groups.

We did not assess compliance with the device. It is conceivable that patients who reported no symptomatic improvement used the device less often.

This study provides anecdotal and quantitative evidence that Ménière's disease patients benefited from the Meniett® device. Of course, it is hard to determine whether symptom improvement was part of the cyclical nature of the condition or due to a placebo effect. However, some patients reported complete abolition of vertigo with continued use. It is noteworthy that any improvement experienced with the Meniett® device occurred in the absence of other forms of treatment.

Several studies of the Meniett® device have been reported, the more notable of which are discussed here. A randomised, placebo-controlled trialReference Gates, Green, Tucci and Telian23 of Meniett® device use over four months, versus grommet alone, demonstrated fewer attacks of vertigo in the former group, with no effect on hearing or electrocochleographic parameters. Further follow upReference Gates, Verrall, Green, Tucci and Telian24 of these patients over two years, with assessment every three months, showed that 67 per cent of patients noticed a reduction in vertiginous attacks, and 47 per cent went into remission during the two year follow-up period. This confirms the long-term remission potential of the Meniett® device. A similar placebo-controlled trialReference Odkvist, Arlinger, Billermark, Densert, Lindholm and Wallqvist25 had comparable findings, and in addition showed improved hearing in the treatment group.

In a randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled studyReference Thomsen, Sass, Odkvist and Arlinger26 of 40 patients with active Ménière's disease, a two month waiting period was observed after grommet insertion and before treatment commencement, to remove any possibility of symptom improvement related to grommet insertion. There was a statistically significant improvement in vertigo (assessed on a visual analogue scale), and a statistically insignificant trend towards reduction in vertigo attack frequency. There were no statistically significant differences between the treatment and placebo groups regarding such secondary end-points as tinnitus perception, aural pressure, and subjective and audiometric measures of hearing.

The modified Seigel's deviceReference Alva27 is analogous to the Meniett® device, and delivers 180–200 mmHg air pulses three times daily using a sphygmomanometer. This device has been recently reported to show good effects in a series of 10 patients, of whom eight showed substantial improvement in vertigo at 18 months, and four developed a hearing gain of >10 dB.

• Ménière's disease is of multifactorial aetiology; treatment often aims to reduce the pressure of the endolymphatic compartment

• The Meniett® device administers low pressure air pulses to the middle ear, which are thought to relieve symptoms by displacing excess inner ear endolymph

• This is the first study to describe the UK experience with the Meniett® device

• The Vertigo Symptom Scale and Glasgow Benefit Inventory were used to demonstrate a positive effect on vertigo control in patients with Ménière's disease

In a survey assessing British consultant otolaryngologists’ management of Ménière's disease,Reference Smith, Sankar and Pfleiderer28 50 per cent of responders reported inserting a grommet as first-line surgical treatment, whilst 52 per cent recommended saccus decompression. However, there was no mention of the Meniett® device, and it was not clear if any patients receiving grommets underwent intra-tympanic chemical labyrinth ablation.

Conclusion

Our study supports use of the Meniett® device as a minimally invasive, well tolerated, first-line surgical treatment for Ménière's disease. This condition is relapsing and remitting, and treatment should be given in the first instance, which has the least chance of causing harm. We therefore advocate that the Meniett® device be allocated a place on the Ménière's disease therapeutic ladder, to be used after medical therapies but before chemical labyrinthectomy with gentamicinReference Smith, Sandooram and Prinsley11, Reference Lange, Maurer and Mann19 or streptomycin,Reference LaRouere, Zappia and Graham29 or the traditional surgical alternatives of vestibular nerve section,Reference Silverstein, Norrell and Rosenberg21 labyrinthectomyReference Pulec30 and endolymphatic sac decompression.Reference Snow and Kimmelman22