Introduction

Epistaxis can be a life-threatening emergency, and requires appropriate and structured initial assessment. In the absence of national guidance, however, it is currently unclear what this initial assessment should entail. Elements of initial assessment commonly include: instigating first aid measures, recording physiological parameters, taking a focused history, performing a clinical examination and requesting appropriate investigations. Within these elements, it is important that any first aid measures undertaken are known to be effective, either as a treatment of epistaxis or a method of limiting bleed severity. Physiological parameters should be used as measures of illness severity, if demonstrated to be valid in this patient group. When taking a focused history, whilst there are many established risk factors for epistaxis, it is key to know what factors affect the outcomes of epistaxis sufferers so that management can be tailored accordingly. The clinical examination must be appropriate to guide relevant intervention, but what should this examination include? At times of financial strain, investigations should be rationed to those known to influence management, but where should the threshold for requesting these tests be?

Aims

This article aimed to systematically review the literature to inform a guideline generation process in order to create national consensus recommendations for the hospital management of epistaxis. This document will include recommendations founded on an evidence-based approach to the initial assessment of epistaxis patients. For the purposes of the article, this management domain was split into two distinct systematic reviews: patient factors affecting outcome and initial management. The specific research questions are described below.

Patient factors affecting outcome

What patient factors affect the outcomes of length of hospital stay, progression to surgery, rate of transfusion of blood products, and rate of associated morbidity and mortality in hospital-treated epistaxis?

Initial management

What represents optimum initial management? Where should initial assessment and management be conducted? Who should be undertaking the initial assessment and management? What first aid measures should be instigated? What observations should be undertaken within the initial assessment? What elements represent appropriate patient examination? What investigations should be performed in all patients? What investigations should be performed in selected patients?

Materials and methods

This work forms part of a set of systematic reviews designed to summarise the literature prior to the generation of a UK national management guideline for epistaxis. Following this and other systematic reviews, consensus recommendations on the management of epistaxis were generated based on the evidence and expert opinion. 1 The methodology set out below is common to this and four other reviews.Reference Mcleod, Price, Williams, Smith, Smith and Owens 2 – Reference Swords, Patel, Smith, Williams, Kuhn and Hopkins 5

Research question generation

The management of epistaxis was divided into nine domains as determined through discussion within a trainee project steering committee. The identified domains were: patient factors affecting outcome, initial assessment and first aid, cautery, dissolvable nasal packs, non-dissolvable nasal packs, management of anticoagulation, other haematological factors affecting outcome, surgical management, and radiological intervention. Clinically relevant research questions were then generated via an iterative consensus process for each domain, to encompass all elements of epistaxis management. Systematic reviews relating to the nine domains have been published in five articles (including this one), and the research questions can be found within the relevant reviews.Reference Mcleod, Price, Williams, Smith, Smith and Owens 2 – Reference Swords, Patel, Smith, Williams, Kuhn and Hopkins 5 Two primary authors led the review of each domain, working with centralised library and steering committee support.

Types of study included

A preliminary review of the literature suggested there was a limited quantity of high-level evidence in many of the domains. As a result, randomised controlled trials (RCTs), controlled and uncontrolled longitudinal studies, and cross-sectional studies were all accepted for analysis. Case series, case reports and opinion-based articles were excluded. Restrictions were not placed on the outcomes used in identified studies at the search stage, in order to ensure capture of all relevant studies.

Types of participant

Relevant studies were included if they related to patients aged 16 years and above treated for epistaxis within a hospital environment. Studies including paediatric cases or cases of bleeding secondary to hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia were included in the analysis only if these patients formed less than 30 per cent of the total case number.

Search restrictions

There were no publication year or publication status restrictions. Only English-language articles were included.

Electronic searches

Initially, two members of the steering committee (MES and RJW) independently generated core Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) and non-MeSH key words to identify relevant studies relating to epistaxis. These were then discussed to create a core list of key words that formed the basis of the individual domain searches. Domain review authors independently generated key words specific to each individual research question, and these were also discussed to reach an agreed list. The key word lists were submitted to two librarians (University of Cambridge Medical Library and Exeter Health Library), who together used the core and specific key words to design a search strategy for each domain systematic review.

The following databases were searched from their inception for published, unpublished and ongoing studies: the Cochrane ENT Disorders Group Trials Register; the Cochrane Library, including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (‘DARE’), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; Medline; Embase; the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (‘CINAHL’); and the Web of Science. Full search strategies can be accessed in the online supplementary material that accompanies this issue. Additional studies were identified from the reference lists of full-text articles identified in searches, and from existing systematic reviews. All searches were performed in February 2016.

Validation of search strategy

To ensure the validity of the search strategy domain, co-authors manually identified two articles relevant to each systematic review. The librarians used these to test the search strategy for each domain, adjusting the strategies if necessary. Finally, the domain review authors were issued the search results (including abstracts) for all identified papers.

Screening and eligibility assessment

The two domain authors independently scrutinised the identified abstracts, and requested full-text articles for any studies that appeared relevant to either author. Records were kept of all excluded studies, including the reasons for their exclusion. When potentially relevant full-text articles could not be obtained through local sources, the Defence Medical Library Service assisted via inter-library loans; articles that were still not obtainable were excluded from data extraction.

Data extraction and management

Continuing to work independently, the two domain authors extracted data from the identified studies into a standardised online form that was designed by the steering committee and librarians, and hosted on Google Drive. Meta-analysis was not routinely performed unless data were of sufficient quantity and quality to make this relevant.

Risk of bias assessment

For the purposes of bias assessment, studies were divided into RCT and non-randomised trials with or without comparators. The assessment of RCT risk of bias was performed using the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias.Reference Higgins, Altman, Gøtzsche, Jüni, Moher and Oxman 6 This tool lists seven potential sources of bias that may affect the internal validity of an RCT, and each is assigned a risk of bias judgement (low, unclear or high). Non-randomised trials were assessed using the methodological index for non-randomised studies (‘MINORS’) criteria.Reference Slim, Nini, Forestier, Kwiatkowski, Panis and Chipponi 7 The score is calculated by awarding 0, 1 or 2 points to multiple criteria (e.g. clearly stated aims), before totalling these to achieve a final value. The methodological index for non-randomised studies score is calculated out of a possible 16, or 24 in the presence of a comparative group, with higher scores representing a lower risk of bias. Authors independently completed relevant bias assessment proformas for each included study.

Data synthesis

Following independent data extraction and assessment of bias, the co-authors for each domain reviewed the extracted information to reach a joint consensus. These data were used to populate a data synthesis table to summarise the findings of the systematic reviews, with the format standardised across the nine domains. If homogeneity permitted, a meta-analysis of key outcomes was performed, with narrative review performed otherwise.

Patient factors affecting outcome

Results

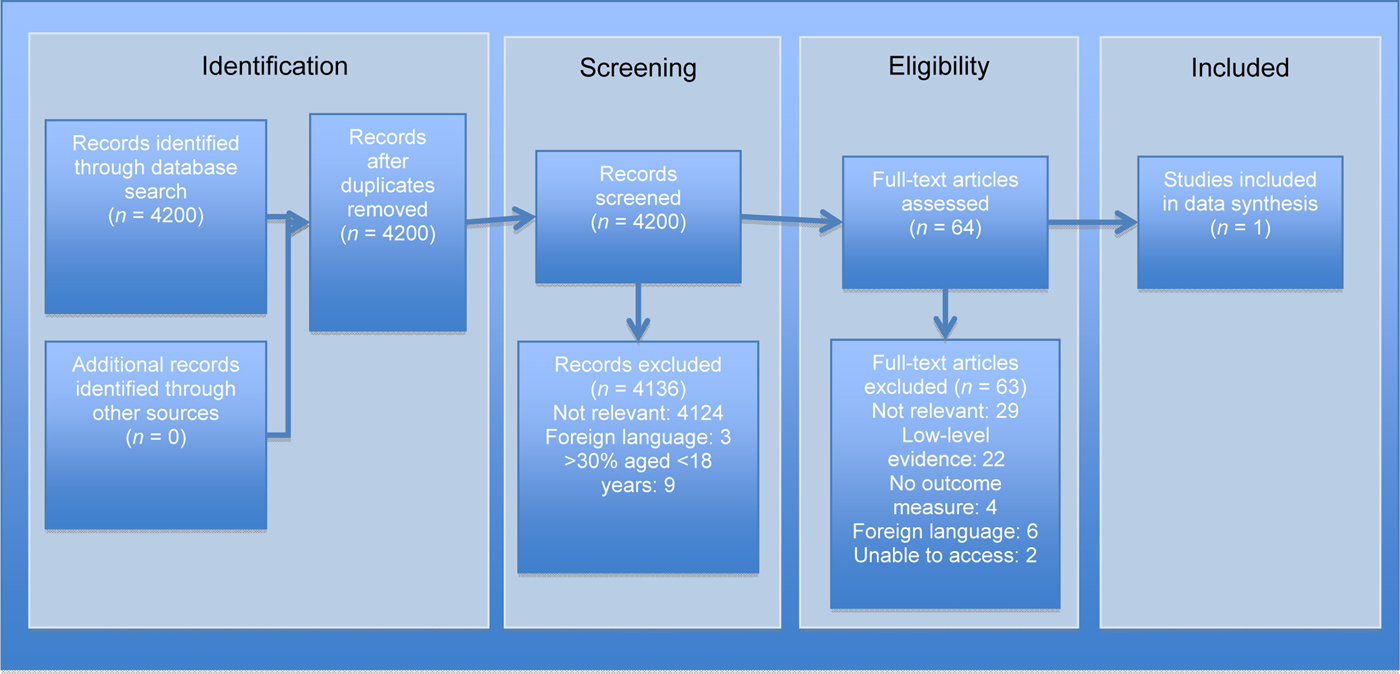

Figure 1 illustrates the search and article selection process. Of the 14 studies included, 1 is a randomised controlled trial (RCT),Reference Kristensen, Nielsen, Gaihede, Boll and Delmar 8 5 are prospective controlled studies,Reference Beran and Petruson 9 – Reference Smith, Siddiq, Dyer, Rainsbury and Kim 13 2 are retrospective controlled longitudinal studies,Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 , Reference Ando, Iimura, Arai, Arai, Komori and Tsuyumu 15 5 are retrospective uncontrolled longitudinal studiesReference Goljo, Dang, Iloreta and Govindaraj 16 – Reference Terakura, Fujisaki, Suda, Sagawa and Sakamoto 20 and 1 is a prospective uncontrolled longitudinal study.Reference Klossek, Dufour, de Montreuil, Fontanel, Peynègre and Reyt 21 The studies varied significantly in sample size, with a range of 16 to 16 828 participants. Subjects’ ages ranged from 0 to 98 years (median = 41.5–81.7 years, mean = 34.2–84.3 years). In terms of sex distribution, 61.4 per cent of participants were male and 38.6 per cent were female overall.

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) diagram for the patient factors review, mapping the number of records identified, included and excluded during different review phases.

The quality of the evidence as assessed by risk of bias was variable, but overall it was poor to fair (Appendix I). The mean methodological index for the non-RCTs was 16.29 ± 3.25 (range, 10–20 out of 24),Reference Beran and Petruson 9 – Reference Ando, Iimura, Arai, Arai, Komori and Tsuyumu 15 and for the uncontrolled non-RCTs it was 10.50 ± 1.38 (range, 8–12 out of 16).Reference Goljo, Dang, Iloreta and Govindaraj 16 – Reference Klossek, Dufour, de Montreuil, Fontanel, Peynègre and Reyt 21 The RCT, which compared re-bleeding rates between epistaxis in-patients who were mobilised with those who were rested, was biased regarding ambiguous concealment of the alternate intervention, with no random allocation to groups, and not all outcomes were reported.Reference Kristensen, Nielsen, Gaihede, Boll and Delmar 8 As the study setting was a busy ward, there was the potential for outcomes to be missed and blinding uncovered.Reference Kristensen, Nielsen, Gaihede, Boll and Delmar 8 None of the studies stated that a sample size calculation had been performed.

Summary of evidence

Co-morbidities

Hypertension

Hypertension appears to be associated with persistent and recurrent epistaxis, as demonstrated by six studies (Table I).Reference Beran and Petruson 9 , Reference Herkner, Laggner, Müllner, Formanek, Bur and Gamper 12 , Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 , Reference Ando, Iimura, Arai, Arai, Komori and Tsuyumu 15 , Reference Purkey, Seeskin and Chandra 19 , Reference Terakura, Fujisaki, Suda, Sagawa and Sakamoto 20

Table I Studies investigating association between hypertension and recurrent epistaxis

HTN = hypertension; BP = blood pressure; NR = not reported; IQR = interquartile range; ICD-9 = International Classification of Diseases, ninth edition

Terakura et al. compared blood pressure in patients with controlled and persistent bleeding following the application of an intranasal dressing with adrenaline and lignocaine. Both a diagnosis of hypertension and elevated systolic blood pressure at presentation were associated with ongoing epistaxis.Reference Terakura, Fujisaki, Suda, Sagawa and Sakamoto 20

Five studies assessed the relationship between hypertension and recurrent epistaxis, of which four were controlledReference Beran and Petruson 9 , Reference Herkner, Laggner, Müllner, Formanek, Bur and Gamper 12 , Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 , Reference Ando, Iimura, Arai, Arai, Komori and Tsuyumu 15 and one uncontrolled.Reference Purkey, Seeskin and Chandra 19 These were larger and of a higher quality, as compared with the included studies overall (mean number of participants (± standard deviation (SD)) = 1124 ± 861; mean methodological index for non-randomised studies scores were 17 out of 24 and 12 out of 16).

Three of the studies (including the uncontrolled studyReference Purkey, Seeskin and Chandra 19 ) demonstrated that recurrent epistaxis was associated with a medical history of hypertension. One of these studies, the only prospective study, also found that sustained hypertension was a significant predictor of recurrent epistaxis, with these patients experiencing a mean of five episodes, as compared with one episode in patients with non-sustained hypertension.Reference Herkner, Laggner, Müllner, Formanek, Bur and Gamper 12

Conversely, two of the studies found no association between hypertension and recurrent epistaxis. Although Beran and Petruson stated no significant difference in the blood pressures of patients with recurrent epistaxis as compared with the general population, the authors did not report the results on which this statement was based.Reference Beran and Petruson 9 In addition, the definition of hypertension in this study could be considered less reliable, with blood pressure measured on a single occasion only. This was then compared with existing data from a much larger population sample dataset (23 794 subjects) rather than a direct cohort. Ando et al. found no significant difference in past medical history of hypertension between patients with single and recurrent episodes of epistaxis.Reference Ando, Iimura, Arai, Arai, Komori and Tsuyumu 15 However, there were large differences between group sizes as the single incident group was 8.3 times larger than the recurrent bleeding group, and follow-up period and attrition were not clearly stated.

Atherosclerosis associated with cardiovascular disease has been proposed as a risk factor in epistaxis.Reference Ibrashi, Sabri, Eldawi and Belal 22 Cardiovascular risk factors including sustained ambulatory hypertension, and anticoagulant and antiplatelet use, appear to be associated with persistent, recurrent or heavier epistaxis.Reference Beran and Petruson 9 – Reference Goljo, Dang, Iloreta and Govindaraj 16 , Reference Purkey, Seeskin and Chandra 19 , Reference Terakura, Fujisaki, Suda, Sagawa and Sakamoto 20 This is of particular relevance, as treating an ageing population with increasing co-morbidities is associated with increasing health and social care responsibility and cost. 23 However, evidence regarding the influence of demographic features and other co-morbidities on the outcome in patients with epistaxis is limited both in quality and number of studies.

Anticoagulation

Six studies (four controlledReference García Callejo, Bécares, Calvo, Martínez, Marco and Marco 10 , Reference Denholm, Maynard and Watson 11 , Reference Smith, Siddiq, Dyer, Rainsbury and Kim 13 , Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 and two uncontrolled studiesReference Goljo, Dang, Iloreta and Govindaraj 16 , Reference Klossek, Dufour, de Montreuil, Fontanel, Peynègre and Reyt 21 ) suggest that anticoagulant use adversely affects the outcome in epistaxis, causing recurrent and heavier bleeding and an increased incidence of blood transfusion. The quality of these studies is similar to that of the studies overall (mean methodological index for non-randomised studies scores of 16 out of 24 and 11 out of 16). Both the largest studyReference Goljo, Dang, Iloreta and Govindaraj 16 and some of the smallest studiesReference Denholm, Maynard and Watson 11 , Reference Klossek, Dufour, de Montreuil, Fontanel, Peynègre and Reyt 21 are represented (mean number of participants (± SD) = 3105 ± 6742; range = 40–16 828 participants).

More frequent and heavier bleeding was associated with anticoagulant use in three studies (Table II).Reference García Callejo, Bécares, Calvo, Martínez, Marco and Marco 10 , Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 , Reference Klossek, Dufour, de Montreuil, Fontanel, Peynègre and Reyt 21 The anticoagulant medications used varied between the studies. In one study, recurrent bleeding was higher in individuals using warfarin, or a combination of warfarin and aspirin. Recurrent bleeding rates were not higher in those using other individual or combination anticoagulants, though sample sizes were too small to draw reliable conclusions.Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 Two prospective studies evaluated the severity of bleedingReference García Callejo, Bécares, Calvo, Martínez, Marco and Marco 10 , Reference Klossek, Dufour, de Montreuil, Fontanel, Peynègre and Reyt 21 A controlled study demonstrated a higher incidence of blood transfusion amongst admitted epistaxis patients taking dabigatran or acenocoumarol, as compared with those taking no anticoagulant.Reference García Callejo, Bécares, Calvo, Martínez, Marco and Marco 10 One uncontrolled study found that patients who had taken any medication associated with increased bleeding risk (anticoagulant or non-anticoagulant) were more likely to present with heavier bleeding, as compared with patients not taking these medications.Reference Klossek, Dufour, de Montreuil, Fontanel, Peynègre and Reyt 21

Table II Studies investigating association between anticoagulation and adverse outcomes

*Antiplatelet medication, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, salicylate derivatives, vitamin K antagonists, beta-lactams, antidepressants and long-term corticosteroid therapy. MINORS = methodological index for non-randomised studies

Three prospective controlled studies found that anticoagulant use was associated with a longer admission.Reference García Callejo, Bécares, Calvo, Martínez, Marco and Marco 10 , Reference Denholm, Maynard and Watson 11 , Reference Smith, Siddiq, Dyer, Rainsbury and Kim 13 This finding was significant in two of these studies, and was attributed, in both studies, to the routine in-patient management of anticoagulation, alongside social and medical conditions.Reference Denholm, Maynard and Watson 11 , Reference Smith, Siddiq, Dyer, Rainsbury and Kim 13 Contemporary practice favours out-patient anticoagulation management, and these results may now be of limited relevance. In the third of these studies, patients with persistent bleeding following removal of nasal packing required a period of observation, which contributed to an increased length of stay in patients taking dabigatran (5.9 ± 1.9 days) and acenocoumarol (4.3 ± 1.1 days), as compared with patients not taking any anticoagulant medication (3.6 ± 2.4 days), but this did not achieve significance.Reference García Callejo, Bécares, Calvo, Martínez, Marco and Marco 10

In a multicentre retrospective longitudinal study, the largest included in this review, Goljo et al. found that 20.8 per cent of 16 828 patients admitted with epistaxis who were taking anticoagulant medication had a significantly lower cost and length of stay, revealed by a multiple linear regression analysis, as compared with the sample in general.Reference Goljo, Dang, Iloreta and Govindaraj 16 Amongst the studied population, the most common co-morbidities were cardiovascular disease (78.5 per cent), type II diabetes (25.4 per cent) and anticoagulant use (20.8 per cent). Factors associated with increased cost and length of stay were: an increased number of chronic co-morbidities, the necessity for operative intervention, Asian or Pacific Islander race (cost), black race (length of stay), top income quartile (cost), private insurance (cost), Medicaid insurance (length of stay), teaching hospital admission (cost), and certain geographical features. Subgroup analyses of patients using anticoagulant medication were not performed; hence, it could not be determined whether any of these confounding factors contributed to the lower cost and length of stay amongst these patients. Furthermore, this study represented patients in the USA, where the practices and pricing of care may differ from those in the UK.Reference Goljo, Dang, Iloreta and Govindaraj 16

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence key therapeutic topic information indicates the use of novel oral anticoagulants in the prevention of a number of serious and common medical conditions, including stroke and some adverse outcomes associated with acute coronary syndromes, and in the treatment and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism and its complications. 24 The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (‘MHRA’) issued a warning of serious haemorrhage risk against three of these drugs that were licensed at the time (apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran). 25 The evidence represented in this review primarily concerns the oral anticoagulant warfarin, with only one study evaluating adverse outcomes in epistaxis patients using novel oral anticoagulants.Reference García Callejo, Bécares, Calvo, Martínez, Marco and Marco 10

Rhinological co-morbidities

Nasal mucosal congestion in rhinitis and rhinosinusitis has been implicated in the aetiology of epistaxis, but there is insufficient evidence to support an association between congestion and patient outcomes. Only one controlled study considered this relationship.Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 When rhinological factors associated with recurrent epistaxis (as compared with a single episode of bleeding) were reviewed, no significant differences were found in terms of the incidence of: rhinitis (2.6 per cent cases vs 1.3 per cent controls), sinusitis (1.1 per cent cases vs 1.3 per cent controls) or upper respiratory tract infection (1.5 per cent cases vs 1.5 per cent controls).Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14

Other co-morbidities

The relationship between other co-morbidities and patient outcomes in epistaxis was considered in one controlledReference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 and one uncontrolled retrospective study.Reference Goljo, Dang, Iloreta and Govindaraj 16 Abrich et al. found that recurrent epistaxis was associated with congestive heart failure (p < 0.001) and diabetes (p = 0.04).Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 In a longitudinal uncontrolled study of 16 828 patients, by Goljo et al., an increasing number of co-morbidities was associated with a longer hospital stay in patients admitted with epistaxis because of the management of co-existing medical conditions (p < 0.001).Reference Goljo, Dang, Iloreta and Govindaraj 16 This study examined patients admitted to multiple centres in the USA, where practices may differ from those in the UK.

Intrinsic risk factors

Bleeding site

Two retrospective longitudinal studies investigated the relationship between anterior and posterior bleeding site and patient outcome. Both studies demonstrated that posterior site epistaxis is more frequently associated with recurrent bleeding.Reference Ando, Iimura, Arai, Arai, Komori and Tsuyumu 15 , Reference Monjas-Cánovas, Hernández-García, Mauri-Barberá, Sanz-Romero and Gras-Albert 18 One of these studies, by Ando et al., reported that anterior bleeding was significantly associated with non-recurrent epistaxis (191 out of 198 patients).Reference Ando, Iimura, Arai, Arai, Komori and Tsuyumu 15 Each non-anterior bleeding site was analysed independently, rather than as posterior epistaxis in general. Failure to identify the bleeding point (in 14 out of 267 single episode patients vs 17 out of 32 recurrent epistaxis patients; p < 0.0001) was also associated with recurrent epistaxis. Bleeding from the olfactory cleft, middle or inferior meati, or other non-anterior site did not achieve significance, though numbers in these subgroups were much smaller than in the anterior bleeding group.Reference Ando, Iimura, Arai, Arai, Komori and Tsuyumu 15

Bleeding severity

Patients with more severe bleeding appear more likely to undergo surgical intervention. In a single, small, retrospective longitudinal study, bleeding severity was compared in patients who underwent sphenopalatine artery ligation (n = 27) versus those who did not (n = 71).Reference Lakhani, Syed, Qureishi and Bleach 17 Four measures of severity were found to be significant predictors for surgery: persistent uncontrolled epistaxis despite anterior and posterior packing (21 out of 27 patients vs 1 out of 71 patients; p < 0.0001); three or more episodes of recurrent bleeding (17 out of 27 patients vs 0 out of 71 patients; p < 0.0001); blood transfusion or haemoglobin decrease of greater than 4 g/dl (9 out of 27 patients vs 4 out of 71 patients; p < 0.0001); and three admissions for ipsilateral bleeding in three months (4 out of 27 patients vs 0 out of 71 patients; p < 0.0001).

Demographic and social history

Patient age was found not to be associated with recurrent bleeding in one retrospective controlled study.Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 Age also appears to have no relationship with continued bleeding after pack removal.Reference Terakura, Fujisaki, Suda, Sagawa and Sakamoto 20

Alcohol intake

Excess alcohol consumption and alcohol-induced platelet dysfunction have been implicated as risk factors for epistaxis.Reference McGarry, Gatehouse and Hinnie 26 , Reference McGarry, Gatehouse and Vernham 27 Evidence relating alcohol intake history to patient outcome in epistaxis is very limited. Based on US admission data, Goljo et al. found that a history of alcohol abuse in epistaxis patients (5.8 per cent; 972 out of 16 828) was associated with a significantly increased length of stay (p = 0.004).Reference Goljo, Dang, Iloreta and Govindaraj 16 In a retrospective, longitudinal controlled trial, Abrich et al. found no difference in alcohol consumption between 426 patients with recurrent epistaxis and 912 matched controls.Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 Though the latter study also compared independent history of portal hypertension and gastrointestinal bleeding between the two groups (neither was significant), neither study considered the influence of any hepatic impairment nor complications of alcohol abuse on the patient outcome.

Patient mobilisation

Patient mobilisation during the hospital stay does not appear to have any effect on re-bleeding rate. The only included RCT found no significant difference between in-patients who were mobilised (21 out of 50) and those confined to bed rest (24 out of 50).Reference Kristensen, Nielsen, Gaihede, Boll and Delmar 8 The mean age of the adult patients with epistaxis in the presented data was 65.4 years, meaning that many patients were above the age of 60 years and therefore at higher risk for the development of venous thromboembolism. 28 Patient mobility plays a key role in the prevention of venous thromboembolism 28 and, on the basis of limited evidence, it would appear sensible for the epistaxis patient to mobilise lightly, without increased risk of re-bleeding.Reference Kristensen, Nielsen, Gaihede, Boll and Delmar 8

Limitations

The primary limitations were low-quality evidence and poor study design, as demonstrated by the methodological index for non-randomised studies criteria, applied to assess the methodological quality of non-randomised surgical studies. There were a lack of prospective controlled trials; only 1 RCT was included,Reference Kristensen, Nielsen, Gaihede, Boll and Delmar 8 and 6 of the 14 included studies were uncontrolled.Reference Goljo, Dang, Iloreta and Govindaraj 16 – Reference Klossek, Dufour, de Montreuil, Fontanel, Peynègre and Reyt 21 The remaining seven studies were retrospective in their methodology.Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 – Reference Terakura, Fujisaki, Suda, Sagawa and Sakamoto 20 Within and between studies, there were fundamental differences in baseline demographic characteristics and co-morbidities for the participant groups compared. Furthermore, heterogeneity of study design and poorly defined outcomes meant that meta-analysis was not possible. Of particular note, definitions of hypertension were inconsistentReference Beran and Petruson 9 , Reference Herkner, Laggner, Müllner, Formanek, Bur and Gamper 12 , Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 , Reference Ando, Iimura, Arai, Arai, Komori and Tsuyumu 15 , Reference Purkey, Seeskin and Chandra 19 , Reference Terakura, Fujisaki, Suda, Sagawa and Sakamoto 20 and there was variation in the anticoagulant medications used in the different studies.Reference García Callejo, Bécares, Calvo, Martínez, Marco and Marco 10 , Reference Denholm, Maynard and Watson 11 , Reference Smith, Siddiq, Dyer, Rainsbury and Kim 13 , Reference Abrich, Brozek, Boyle, Chyou and Yale 14 , Reference Goljo, Dang, Iloreta and Govindaraj 16

Initial management

Results

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the search and article selection process for the first aid and initial assessment parts of this review. Three studies were included, of which none were randomised controlled trials. Two were prospective controlled studies concerning ‘first aid’ measures, with a total number of 72 participants (16 and 56 participants). Both papers assessed the effect of topical ice packs on nasal mucosal blood flow in healthy volunteers, as measured by laser Doppler flowmetry at Kiesselbach's plexusReference Teymoortash, Sesterhenn, Kress, Sapundzhiev and Werner 29 or the inferior turbinate.Reference Porter, Marais and Tolley 30 The studies were of a fair quality overall (Appendix II): both demonstrated a methodological index for non-randomised studies score of 17 out of 24, with robust, simple and reproducible methodology. A single retrospective uncontrolled longitudinal study relevant to ‘initial assessment’ of the epistaxis patient was of fair quality (Appendix III): the methodological index for non-randomised studies score was 8 out of 16.Reference Thaha, Nilssen, Holland, Love and White 31 This study reviewed the use of coagulation studies in 183 cases.

Fig. 2 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) diagram for the first aid review, mapping the number of records identified, included and excluded during different review phases.

Fig. 3 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) diagram for the initial assessment review, mapping the number of records identified, included and excluded during different review phases.

Summary of evidence

First aid

Various first aid measures have been adopted for epistaxis treatment, despite a lack of evidence. The only first aid measure described in the included studies was the use of an ice pack. The application of an intra-oral ice pack has the potential to decrease nasal blood flow, and this may in turn decrease epistaxis severity, although this has yet to be demonstrated. In one study, intra-oral ice significantly reduced the nasal blood flow at the inferior turbinate (23 per cent), as compared with a control pack (5 per cent, p < 0.05).Reference Porter, Marais and Tolley 30 An ice pack placed on the forehead failed to achieve a significant reduction in nasal blood flow.Reference Teymoortash, Sesterhenn, Kress, Sapundzhiev and Werner 29 , Reference Porter, Marais and Tolley 30 In one of these studies, the standard deviations in mean blood flow following forehead application in both participant groups were very large, suggesting heterogeneity amongst individual results within a small study (1368.8 ± 927.9 before vs 1130.5 ± 792.2 after; p = 0.11).Reference Teymoortash, Sesterhenn, Kress, Sapundzhiev and Werner 29

Initial assessment

Coagulation screening may be of benefit only in epistaxis patients on anticoagulant therapy or in those with a history of bleeding diatheses, as results are otherwise likely to be normal and do not add to the management process. An abnormal result is of clinical value and can guide overall management. In a retrospective longitudinal study, over a period of one year, Thaha et al. found that 10 epistaxis patients who had abnormal coagulation study results (out of a total of 121; 8.3 per cent) were using the oral anticoagulant warfarin, and no other coagulation abnormalities were identified in the studied population.Reference Thaha, Nilssen, Holland, Love and White 31 This is the only included study relevant to the role of coagulation screening.

A single uncontrolled retrospective study set in a large Scottish teaching hospital is included in the ‘Initial assessment’ section of the review.Reference Thaha, Nilssen, Holland, Love and White 31 Of all the epistaxis patients who underwent coagulation studies, only 8.3 per cent of results were abnormal. Furthermore, these were exclusive to patients using the oral anticoagulant warfarin.Reference Thaha, Nilssen, Holland, Love and White 31 Although, at the time of this review, there is an absence of data representing the frequency and cost of coagulation screening in UK epistaxis patients, considerable cost savings could likely be achieved with more judicious use of the tests.

Limitations

Despite a potentially extensive theme, only two topics were represented within the first aid and initial assessment review.Reference Teymoortash, Sesterhenn, Kress, Sapundzhiev and Werner 29 – Reference Thaha, Nilssen, Holland, Love and White 31 This is because of the lack of published studies. The primary limitations of the identified studies were low-quality evidence and study design. The controlled studies did not declare adequate power.Reference Teymoortash, Sesterhenn, Kress, Sapundzhiev and Werner 29 , Reference Porter, Marais and Tolley 30 Both controlled studies within the ‘First aid’ section studied the effect of ice pack application on nasal blood flow in healthy, young volunteers, with a median age of 31 years between the studies.Reference Teymoortash, Sesterhenn, Kress, Sapundzhiev and Werner 29 , Reference Porter, Marais and Tolley 30 This healthy, young group is not representative of that seen clinically, with a median age of patients within the ‘Patient factors’ review of 66 years,Reference Kristensen, Nielsen, Gaihede, Boll and Delmar 8 , Reference García Callejo, Bécares, Calvo, Martínez, Marco and Marco 10 – Reference Monjas-Cánovas, Hernández-García, Mauri-Barberá, Sanz-Romero and Gras-Albert 18 , Reference Terakura, Fujisaki, Suda, Sagawa and Sakamoto 20 , Reference Klossek, Dufour, de Montreuil, Fontanel, Peynègre and Reyt 21 and co-morbidities were present in 58.6 per cent of these patients overall (where stated).Reference Kristensen, Nielsen, Gaihede, Boll and Delmar 8 , Reference García Callejo, Bécares, Calvo, Martínez, Marco and Marco 10 , Reference Smith, Siddiq, Dyer, Rainsbury and Kim 13 – Reference Goljo, Dang, Iloreta and Govindaraj 16 , Reference Monjas-Cánovas, Hernández-García, Mauri-Barberá, Sanz-Romero and Gras-Albert 18 , Reference Klossek, Dufour, de Montreuil, Fontanel, Peynègre and Reyt 21

Conclusion

Cardiovascular risk factors, particularly sustained ambulatory hypertension, and anticoagulant or antiplatelet use, appear to be associated with persistent, recurrent or heavier epistaxis. When assessing a patient with epistaxis, a history of cardiovascular disease and medications should be sought. In addition, where possible, the site of bleeding should be identified and recorded, as posterior or unidentified site bleeding can be associated with recurrent or recalcitrant epistaxis.

The application of an intra-oral ice pack is a simple first aid measure with the potential to decrease bleeding severity, and this should be considered from the onset of epistaxis to the point of hospital care. Evidence supporting the efficacy of other topical ice packs is insufficient. There is limited evidence to suggest that coagulation studies should be reserved for patients taking anticoagulant medication or those with a history of bleeding diatheses, as they do not add to the management process in other individuals.

In order for robust recommendations to be made, based on the findings of this review, future adequately powered, randomised controlled studies should address effective methods of first aid, initial assessment and investigation protocols, and determine how to best manage co-morbidities in epistaxis patients via a multidisciplinary approach.

Acknowledgement

This review was part of an epistaxis management evidence appraisal and guideline development process funded by ENT-UK. The funding body had no influence over content.

Appendix I Summary of studies included in patient factors review

Appendix II Summary of studies included in first aid review

Appendix III Summary of studies included in initial assessment review