Introduction

The concept of the clinical care pathway in healthcare dates back to 1974, when Shoemaker described how a ‘critical path’ could be used to evaluate and standardise care, serve as a benchmark for the quality of hospital healthcare services, and educate healthcare providers.Reference Shoemaker1, Reference Coffey, Richards, Remmert, LeRoy, Schoville and Baldwin2 In the modern healthcare era, the goals of a well-designed, evidence-based, multidisciplinary clinical care pathway include the establishment of an organised sequence of specific healthcare interventions, the efficient allocation of resources, and the minimisation of unnecessary delays in care, with measurable improvement in healthcare quality.Reference Rotter, Kinsman, James, Machota, Gothe and Willis3–Reference Yueh, Weaver, Bradley, Krumholz, Heagerty and Conley5

A Cochrane Database review published in 2010 described the utilisation of clinical care pathways for medical conditions ranging from diabetes to pneumonia, and procedures or interventions as varied as prostate surgery, mechanical ventilation and stroke rehabilitation.Reference Rotter, Kinsman, James, Machota, Gothe and Willis3 Many authors believe that clinical care pathways already have demonstrated notable success in endeavours such as these and thus should be used more widely in medicine.Reference Yueh, Weaver, Bradley, Krumholz, Heagerty and Conley5–Reference Wachtel, Moulton, Pezzullo and Hamolsky9 Indeed, it is estimated that more than 80 per cent of all hospitals in the USA already use clinical care pathways for at least some patients.Reference Saint, Hofer, Rose, Kaufman and McMahon10

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, multiple institutions reported using clinical care pathways to manage patients following major head and neck oncological surgery, laryngectomy, composite resection, and neck dissection.Reference Yueh, Weaver, Bradley, Krumholz, Heagerty and Conley5, Reference Chen, Callender, Mansyur, Reyna, Limitone and Goepfert11–Reference Levin, Ferraro, Kodosky and Fedok17 In recognition of the potential value of standardising the care of complex head and neck microvascular free tissue transfer patients, the senior author enacted an interdisciplinary post-operative clinical care pathway and an associated computerised order set for the primary purpose of improving patient outcomes, with the secondary goals of streamlining care, providing clinically relevant medical education, and reinforcing lines of communication amongst healthcare providers. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of the clinical care pathway on length of hospital stay and 30-day readmission rates, as well as overall costs, and effectiveness in reducing adverse outcomes and unplanned reoperations, through a historical comparison of head and neck free tissue transfer patient cohorts before and after clinical care pathway implementation.

Materials and methods

Clinical care pathway development

An interdisciplinary team, consisting of head and neck reconstructive surgeons and otolaryngology residents, allied health professionals, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, physical and occupational therapists, and information technology specialists, convened to develop a comprehensive clinical care pathway (Appendix 1), as well as a computerised order set accessible via the hospital electronic health record system.

The clinical care pathway was designed to address areas for improvement in the post-operative management of head and neck free tissue transfer patients, based on the experience of all above parties, feedback from multiple other healthcare providers at our institution, and a comprehensive medical literature search on the design and efficacy of clinical care pathways. Guidelines developed during this process were scheduled on a specific timeframe, and recommendations for a typical length of hospital stay were made.

The final result, a paper record of the suggested pathway for post-operative free tissue transfer patient care and the computerised order set, was then approved by the Forms Committee at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center (Ohio, USA).

Throughout the process of standardising post-operative patient care, the clinical care pathway was reviewed with the multidisciplinary team, all nursing and allied healthcare professionals. A copy of the clinical care pathway was kept in the patient's bedside chart. A clinical care order set mirrored the pathway. Progression along the pathway was monitored by the intensive care unit and ENT teams.

Study population

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained to perform a retrospective analysis of all patients aged over 18 years who underwent head and neck free tissue transfer procedures by a single reconstructive surgeon (YJP) at the University of Cincinnati Academic Health Center.

Eligible patients were divided into two cohorts. The first cohort, serving as the historical control group, comprised 81 consecutive patients who were treated from 2007 to 2008, prior to clinical care pathway implementation. The second cohort included 46 consecutive patients who had their surgery after clinical care pathway implementation, from 2008 to 2009.

Demographic patient data (including age, gender, race and insurance status) and patient co-morbidities (including active tobacco and/or alcohol abuse, history of pre-operative chemotherapy or radiotherapy to the head and neck, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypothyroidism, renal disease, and liver disease) were reviewed and recorded in the study population database.

Primary outcomes were total length of hospital stay and hospital readmissions within 30 days of hospital discharge. Other reported outcome variables were peri-operative complications, unplanned reoperations and total hospital costs.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated, including means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges for continuous variables, and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. Distributions were assessed for normality using histograms and box plots. Differences in proportions of categorical variables pre- and post-clinical care pathway implementation were tested using a chi-square or Fisher's exact test. Differences in mean age and mean of the combined age Charlson Comorbidity IndexReference Charlson, Szatrowski, Peterson and Gold18 pre- and post-clinical care pathway implementation were tested using an independent t-test. Pre- and post-clinical care pathway implementation changes in median length of hospital stay and cost were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Logistic regression models were used to examine differences in peri-operative complications, unplanned reoperations and readmissions, adjusting for covariates. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA), was used for all analyses.

Results

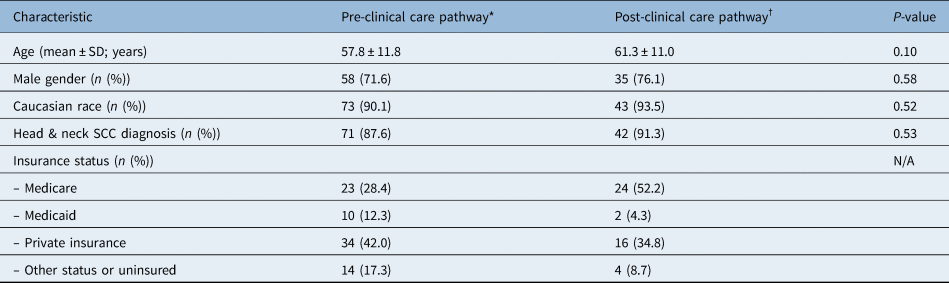

A total of 127 patients were included in the study: 81 in the pre-clinical care pathway group and 46 in the post-clinical care pathway group. Pertinent demographic data for each cohort are provided in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, gender, ethnicity (Caucasian vs non-Caucasian), and the number of patients who underwent free tissue transfer surgery for a diagnosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Patient insurance status was recorded, but differences in the types of insurance carried by patients within each cohort were not tested.

Table 1. Patient demographics

*n = 81; †n = 46. SD = standard deviation; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma; N/A = not applicable

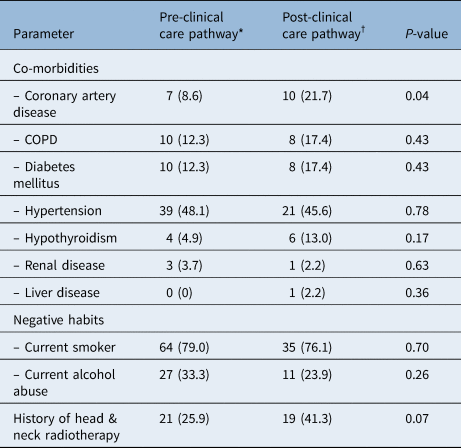

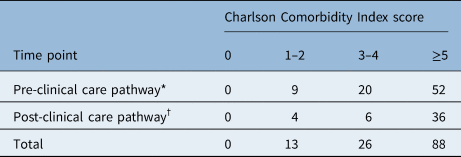

The majority of patients had at least one co-morbidity and/or negative lifestyle habit; findings for the two groups are summarised in Table 2. In order to capture the severity of morbidity, we used the Charlson Comorbidity Index (Table 3). There was a greater proportion of patients with coronary artery disease in the post-clinical care pathway implementation group, but no other significant differences in patient co-morbidities or in the Charlson Comorbidity Index (p = 0.6) between the pre- and post-clinical care pathway cohorts. The most common patient co-morbidities were: hypertension (47.2 per cent), diabetes (14.2 per cent), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (14.2 per cent) and coronary artery disease (13.4 per cent), whilst the most common negative lifestyle habits were smoking (77.9 per cent) and alcohol abuse (29.9 per cent). In addition, 31.5 per cent of patients had received prior head and neck radiation.

Table 2. Patient co-morbidities and other risk factors

Data represent numbers (and percentages) of cases, unless indicated otherwise. *n = 81; †n = 46. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Table 3. Combined age Charlson Comorbidity Index distribution

Data represent numbers of patients. *Mean score = 6.21; †mean score = 6.41

Comparison of measured outcomes between the pre- and post-clinical care pathway cohorts are displayed in Table 4. Whilst it was not associated with a statistically significant reduction in overall length of hospital stay, the implementation of a clinical care pathway was associated with decreased variability in length of hospital stay (median (interquartile range) was 8 (6, 11) pre-clinical care pathway implementation vs 7 (6, 9) post-clinical care pathway implementation; Table 3).

Table 4. General patient outcomes

*n = 81; †n = 46. LOS = length of stay; IQR = interquartile range

Thirty-six subjects underwent a total of 54 reoperations. Four patients had two different acute diagnoses that necessitated reoperation. The most important causes for reoperation were bleeding and fistula formation for both groups (Table 5). The post-clinical care pathway cohort also had a significantly lower unplanned reoperation rate (15.2 per cent, compared to 35.8 per cent pre-clinical care pathway implementation; p = 0.01).

Table 5. Reasons for reoperation

*n = 29; †n = 7; ‡n = 36

A multivariable logistic regression model examining unplanned reoperations indicated that post-clinical care pathway patients had roughly one-third the odds of having an unplanned reoperation (odds ratio = 0.30 (95 per cent confidence interval = 0.11–0.81)) compared to pre-clinical care pathway patients, after adjusting for the important covariates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and Medicaid insurance (Table 6 and Figure 1).

Table 6. Unadjusted and adjusted values from logistic regression model of unplanned reoperation*

* n = 127. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; BMI = body mass index; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Fig. 1. Probability of reoperation pre- and post-clinical care pathway (CCP) implementation from multivariable regression model, adjusted for covariates (Medicaid insurance, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)). The probability of reoperation for each combination of covariates pre-clinical care pathway implementation (circles) is shown. Dotted lines represent the decrease in probability to the levels post-clinical care pathway implementation (plus signs). For example, pre-clinical care pathway patients with Medicaid insurance who had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had an 84.4 per cent probability of reoperation, which reduced to 62.4 per cent post-clinical care pathway implementation.

Post-operative readmissions within 30 days in the post-clinical care pathway group decreased, but this finding was not statistically significant (23.5 per cent pre-clinical care pathway implementation vs 13.0 per cent post-clinical care pathway implementation; p = 0.16). Clinical care pathway implementation was not associated with a significant change in overall hospital costs.

There were no significant differences between the pre- and post-clinical care pathway groups in regard to peri-operative mortality and the majority of major morbidities (e.g. myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia wound infection), and no differences in other conditions (e.g. alcohol abuse, tracheostomy tube plug).

The only significant difference noted regarding peri-operative complications was a decrease in fistula rates following implementation of the clinical care pathway (9.9 per cent in the pre-clinical care pathway cohort vs 0 per cent in the post-clinical care pathway cohort; p = 0.05).

Discussion

The ‘clinical care pathways’ topic became popular in the 1990s, and regained interest recently because of the re-emerging discussion on healthcare costs and the renewed focus on quality of care. Many authors consider clinical care pathways to be an efficient tool to improve patient care and standardise practices. In fact, by setting a specific progression and timing for the established care interventions required for a particular patient population or disease process, clinical care pathways help to reduce the variability in patient care and may present a way to optimise outcomes.

Clinical care pathways have been implemented more frequently for surgical procedures, where the post-procedure hospital course is usually more predictable and some pre-set routine interventions may already be in place.Reference Campbell, Hotchkiss, Bradshaw and Porteous19 Previous studies have demonstrated the benefits of clinical care pathway implementation for various procedures such as cardiac and orthopaedic surgical procedures amongst others.Reference Every, Hochman, Becker, Kopecky and Cannon20, Reference Renholm, Leino-Kilpi and Suominen21 The reported benefits of clinical care pathway implementation include reduced length of hospital stay, decreased costs, improved patient quality of life, fewer complications and increased patient satisfaction.Reference Gordon and Reiter22–Reference Dowsey, Kilgour, Santamaria and Choong26

Head and neck oncological surgery includes a broad array of complex and often morbid resections, followed by reconstruction with local, regional or free tissue transfer. This patient population often has multiple co-morbidities as well as complex socio-economic needs. Clinical care pathways implemented in the post-operative care of head and neck surgery patients require co-ordination between multiple services, including respiratory, speech, physical and occupational therapy, dietary specialist and social work.Reference Gordon and Reiter22

Whilst a number of previously published studies have reported on the use of clinical care pathways in head and neck surgery, few of these studies particularly addressed the application of clinical care pathways for patients who underwent free tissue transfer to the head and neck. In a 2016 systematic review, Gordon and Reiter studied the effectiveness of critical care pathways for head and neck cancer surgery, and found that clinical care pathways may improve outcomes such as length of hospital stay and cost of care, whilst maintaining a high quality of care for patients with head and neck cancer surgery.Reference Gordon and Reiter22 Their review included 10 studies, of which 5 were related to all head and neck surgery cases,Reference Cohen, Stock, Andersen and Everts12,Reference Gendron, Lai, Weinstein, Chalian, Husbands and Wolf13,Reference Husbands, Weber, Karpati, Weinstein, Chalian and Goldberg15,Reference Kagan, Chalian, Goldberg, Rontal, Weinstein and Prior16,Reference Chalian, Kagan, Goldberg, Gottschalk, Dakunchak and Weinstein27 4 were related to total laryngectomy cases,Reference Yueh, Weaver, Bradley, Krumholz, Heagerty and Conley5,Reference Hanna, Schultz, Doctor, Vural, Stern and Suen14,Reference Levin, Ferraro, Kodosky and Fedok17,Reference Sherman, Matthews, Lampe and LeBlanc28 and 1 was exclusively related to neck dissections.Reference Chen, Callender, Mansyur, Reyna, Limitone and Goepfert11 Of these studies, none was specifically designed to evaluate clinical care pathways for patients who had undergone free tissue transfer.

The addition of free tissue transfer to any procedure increases the level of complexity and variability, and will require the addition of specific post-operative care and interventions.Reference O'Connell, Barber, Klein, Soparlo, Al-Marzouki and Harris29 Clinical care pathways specifically designed to manage the post-operative care following free tissue transfer to the head and neck constitute a potential approach to standardise the care, whilst improving outcomes in this patient population.Reference Pearson, Goulart-Fisher and Lee8 Our results demonstrated that the implementation of a clinical care pathway designed for the post-operative care of patients who undergo free tissue transfer to the head and neck significantly reduced the variability of total length of hospital stay. Our findings provide evidence that the use of clinical care pathways in this patient population can standardise patient care.

Yetzer et al. reported a decrease in total length of hospital stay in their study after the implementation of a clinical care pathway for head and neck free tissue transfer.Reference Yetzer, Pirgousis, Li and Fernandes30 Although our results did not demonstrate a statistically significant decrease in length of hospital stay between the two groups, there was a decrease in the median length of hospital stay and interquartile range for the post-clinical care pathway group. It is important to emphasise that the length of hospital stay for free tissue transfer cases is usually on the higher end of the spectrum and is very variable; a mean length of hospital stay of up to 20 days has been reported in the literature.Reference O'Connell, Barber, Klein, Soparlo, Al-Marzouki and Harris29 Our study did demonstrate a significantly decreased variability in the length of hospital stay with clinical care pathway implementation in this complex patient population.

Our results showed a decrease in the peri-operative fistula rates after the implementation of the clinical care pathway. This finding may be partially explained by the scheduled and standardised wound care interventions in the clinical care pathway group. Similar reductions in post-operative surgical and medical complications have been described by other authors after the implementation of a clinical care pathway. Specifically, Yeung et al. reported a reduction in post-operative pulmonary complications in head and neck free tissue transfer patients following clinical care pathway implementation.Reference Yeung, Dautremont, Harrop, Asante, Hirani and Nakoeshny31

Our findings also demonstrated that the use of a specific clinical care pathway for head and neck patients significantly decreased unplanned reoperation rates. To our knowledge, this has not been reported previously. The institution of a clinical care pathway did not reduce the frequency of the most common causes of reoperation (bleeding and fistula). Although the rate of reoperations because of fistulas was similar in both groups, the rate of fistulas as a peri-operative complication decreased significantly following clinical care pathway implementation. The lower unplanned reoperation rates and the downward trend in 30-day readmission rates seen in the post-clinical care pathway group are additional indicators of the importance of a clinical care pathway in providing improved care and resource utilisation. By standardising the multidisciplinary care of these complex patients, we were able to avoid serious complications that might necessitate reoperation, and managed these complications in a non-surgical manner.

We instituted a clinical care pathway to standardise the care of head and neck free tissue transfer undertaken at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center. For the senior author, this was the second head and neck microvascular reconstruction programme he had initiated. He has another set of 118 patients within a head and neck microvascular reconstruction programme (2003–2007) at another academic medical centre; none of these patients were included in this study. Therefore, the learning curve of the principal investigator had matured prior to the current study, and does not explain the improved outcomes in the post-clinical care pathway cohort.

Although no significant surgical or demographic differences exist between the two cohorts, the development and institution of a clinical care pathway resulted in several notable changes that explain the improved outcomes in the post-clinical care pathway group. Notably, the creation of a pathway standardised the post-operative intensive care unit management of these complex patients by localising all their care to a designated unit, wherein the otolaryngology service co-managed these patients with a critical care anaesthesia team. We also trained allied healthcare members, such as nurses, dieticians, social workers and respiratory therapists, to assist in the care of these patients. The allocation of healthcare resources and the training of allied healthcare members resulted in the differences observed in the post-clinical care pathway cohort.

Limitations of this study include the fact that it is retrospective in nature. It involved using the records of a pre-clinical care pathway historical cohort for comparative baseline data. This limitation is common in clinical care pathway studies and makes it challenging to randomise patients to a ‘no pathway’ study arm. The single institution setting may also be a limitation that potentially prevents generalisation of the study results. Testing in a multicentre study using a unique clinical care pathway for all patients is required to overcome this limitation. Finally, the type of defect being reconstructed and the type of free flap used may play a pivotal role in the post-operative course. These variables were not accounted for; this is a recognised study limitation that is difficult to overcome given the small sample sizes available for subgroup analyses or if only one defect type or one free flap type were included.

• The clinical care pathway concept concerns the establishment of interventions with measurable improvement in healthcare quality

• The senior author enacted an interdisciplinary post-operative clinical care pathway to improve complex head and neck patients’ outcomes

• The clinical care pathway is a safe and successful means of standardising and improving complex patient care

Conclusion

The implementation of a multidisciplinary clinical care pathway for patients undergoing head and neck surgery with free tissue transfer was effective in reducing: the variability in total length of hospital stay, the unplanned reoperation rates and the fistula occurrence rates in this patient population. The clinical care pathway is a safe and successful means of standardising and improving complex patient care. The drive behind care pathway development is mainly to improve care efficiency, and resource allocation and utilisation. Whilst most studies reporting on care pathways have shown a reduction in length of hospital stay and hospital costs, both markers of care efficiency, our study showed that care pathway implementation can lower the unplanned reoperations rates too and plays an important role in quality improvement.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Gordon H Sun and Eric Gantwerker for their contribution to this work.

Competing interests

None declared

Appendix 1. Critical care pathway

Glossary of critical care pathway

POD = post-operative day; NPO = nothing by mouth; CAM = controlled ankle movement; RFFF = radial forearm free flap; VAC = vacuum-assisted closure; STSG = split thickness skin graft; OR = operating room; ALT = anterior lateral tight; PRN = as needed; H2O2 = hydrogen peroxide; TID = three times a day; HOB = head of bed; CCAT = critical care anaesthesia team; MD = medical doctor; SNF = skilled nursing facilities; LTAC = long-term acute care; ORL = otorhinolaryngology; PT = physical therapy; C & DB = cough and deep breath; SpO2 = oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry; IV = intravenous; GT/PO = gastrointestinal tract/per oral; CBC = complete blood count; SLP = speech and language pathologist; TF = tube feed