Introduction

Hearing loss has increasingly been recognised as a significant public health burden. Currently, over 1.3 billion individuals are estimated to have age-related or adult-onset hearing loss,Reference James, Abate, Abate, Abay, Abbafati and Abbasi1 with over 430 million of those having moderate (over 40 dB HL) or worse hearing loss.2 This figure is projected to reach 630 million by 2030, and surpass 900 million by 2050.2 Much of the global burden of hearing loss is due to age-related hearing loss, which accounts for 90 per cent of cases worldwide,Reference James, Abate, Abate, Abay, Abbafati and Abbasi1 as opposed to congenital hearing loss, where the prevalence has remained relatively constant in high-income countries, at 0.5 per cent.Reference Graydon, Waterworth, Miller and Gunasekera3 Based on the US population, the prevalence of age-related hearing loss roughly doubles with each decade of age, affecting 13 per cent of adults aged 50–59 years, to over 80 per cent of those aged 80 years and older.Reference Goman and Lin4 In 2002, hearing loss was ranked as the 13th largest contributor to the global burden of disease, estimated to increase to the 9th by 2030,Reference Mathers and Loncar5 and it is the 4th largest cause of disability globally, with an attributed annual cost of 750 billion US dollars.6

Hearing loss has been linked to a myriad of negative health outcomes including, but not limited to, dementia,Reference Lin and Albert7 falls,Reference Lin and Ferrucci8 depressionReference Mener, Betz, Genther, Chen and Lin9 and increased risk of hospitalisation.Reference Genther, Betz, Pratt, Martin, Harris and Satterfield10 The burden of age-related hearing loss will increase because of population growth and an ageing global population.6

In addition to its effects on health, hearing loss has been postulated to impact work status negatively, via unemployment, underemployment and related outcomes. Individuals with hearing loss report increased levels of stress at work and decreased job control, which is the ability of individuals to influence their work environments.Reference Kramer, Kapteyn and Houtgast11 Increased difficulty communicating, among other factors, has been hypothesised to decrease employment status among adults with hearing loss through increased stress, fatigue, burnout, and social isolation at work.Reference Kramer, Kapteyn and Houtgast11

Though age-related and adult-onset hearing loss represent much of the overall burden, most of the existing literature on hearing loss and employment has focused on individuals with congenital hearing loss and/or those who identify as culturally deaf. Much research has been conducted on the association between congenital hearing loss, education and employment. Unrecognised congenital hearing loss has been shown to have a substantial effect on language development, communication skills and behaviour at school, leading to poorer employment outcomes as adults, although early hearing and language intervention significantly reduces this effect.Reference Vohr, Jodoin-Krauzyk, Tucker, Johnson, Topol and Ahlgren12 Recently, even mild hearing loss in children has been associated with poorer academic performance.Reference Bess, Dodd-Murphy and Parker13,Reference Khairi Md Daud, Noor, Rahman, Sidek and Mohamad14 Educational status has a substantial impact on future employment and income among younger individuals with hearing loss.Reference Walter and Dirmyer15,Reference Schley, Walter, Weathers, Hemmeter, Hennessey and Burkhauser16 Thus, childhood hearing loss, through its impact on education, may lead to decreased employment outcomes, with one study from Finland demonstrating this association in adolescents.Reference Järvelin, Mäki-Torkko, Sorri and Rantakallio17

Although the association between childhood hearing loss, education and later employment is well-accepted, the impact of adult-onset hearing loss on employment is less clear. The training and employment of individuals with congenital versus later-onset hearing loss substantially differ. Those with congenital hearing loss have lower rates of university-level education (13 per cent vs 25 per cent) and higher rates of unemployment (31 per cent vs 12 per cent) compared to those with adult-onset hearing loss, indicating two distinct populations.Reference Parving and Christensen18

Determining the relationship between adult-onset hearing loss and employment is crucial in light of an ageing population and the ageing workforce that accompanies this demographic shift. In the USA, the percentage of the population aged 65 years or older is expected to increase to 19 per cent in 2030, from 13 per cent in 2010.19 In parallel, the proportion of the workforce aged over 55 years is projected to reach 25 per cent by 2020, up from 20 per cent in 2010.20 Globally, 80 per cent of the older adult population is anticipated to be living in low- and middle-income countries.21

As the number and diversity of working individuals potentially affected by adult-onset or age-related hearing loss continues to grow, it is increasingly important to: understand whether hearing loss influences employment, examine the possible underlying mechanisms, and, most importantly, explore the potential interventions. Hearing loss may also influence earning potential and income through similar, but possibly different, mechanisms. This study aimed to summarise currently available evidence on the association between adult-onset hearing loss and employment, focusing on unemployment, underemployment, and related outcomes such as occupational class.

Materials and methods

This systematic review follows guidelines set by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) statement.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman22 A pilot search was conducted to identify target articles and key words. After consulting with the research team, an informationist constructed and performed the search strategy.

A total of seven databases (PubMed via PubMed.gov, Embase via Embase.com, the Cochrane Library via Wiley, ABI/Inform® Collection via ProQuest, Business Source Ultimate via EBSCOhost, Web of Science via Clarivate, and Scopus via Elsevier) were searched on 23 October 2018. These searches utilised controlled vocabulary, such as medical subject headings (MeSH terms) and Embase subject headings (‘Emtree’ terms), where appropriate, in combination with key word terms related to the concepts of employment and hearing loss. An effort was made to account for synonyms, antonyms, acronyms and variations in spelling. No limit was made to language or publication type, but the ABI/Inform Collection search was limited to scholarly journals.

The full search strategies for each database can be found in Appendix 1. The initial search resulted in 13 144 results, 5435 of which were duplicates and removed, leaving 7709 articles. Additional removal of duplicates resulted in a total of 7494 articles, which underwent title and abstract screening.

Two reviewers independently screened the title and abstract of each article according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria aimed to capture all articles investigating hearing loss, measured either subjectively or objectively, in relation to unemployment, underemployment, job type or job status. Exclusion criteria included non-primary research, articles focused on paediatric populations (aged less than 18 years), congenital hearing loss, deaf or culturally deaf patients, and those without a normal-hearing control group.

Each title and abstract was classified into ‘Yes’, ‘Maybe’ and ‘No’ categories. Conflicts were resolved between the two reviewers in conjunction with a third collaborator. All articles in the ‘Yes’ and ‘Maybe’ categories underwent full-text review, which was conducted using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as the title and abstract screening. Articles were classified into ‘Include’ and ‘Exclude’ categories; any conflicts were subsequently resolved between the two reviewers and a third collaborator.

Data extraction was performed on these articles by two independent reviewers. The data extracted included: study authors, publication year, study setting, study design, data source, sample characteristics, hearing loss definition and study findings summary. All articles were scored according to the adapted Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cross-sectional studies (see supplementary material in Herzog et al.Reference Herzog, Álvarez-Pasquin, Díaz, Del Barrio, Estrada and Gil23), where points were assigned according to the checklist. Each study's findings regarding the relationship between hearing loss in adults and employment were summarised qualitatively. Because of the heterogeneity among study designs, a meta-analysis was not performed.

Results

Out of the 7494 articles that underwent title and abstract screening, 243 proceeded to full-text review. Of these, 206 were excluded because of various criteria (Figure 1), and 12 were excluded because full texts could not be located through library services. There were 25 articles that met the inclusion criteria.Reference Kramer, Kapteyn and Houtgast11,Reference Walter and Dirmyer15,Reference He, Luo, Hu, Gong, Wen and Zheng24–Reference Roberts and Cohrssen46 Tables 1–4 summarise the characteristics and key findings of the included studies.

Fig. 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) flow chart.

Table 1. Association between hearing loss and unemployment: studies investigating unemployment or underemployment

*Adapted Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale.Reference Herzog, Álvarez-Pasquin, Díaz, Del Barrio, Estrada and Gil23 HL = hearing loss; NR = not reported; ICD9CODX = International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision code for condition

Table 2. Association between hearing loss and unemployment: studies investigating unemployment or underemployment and occupation class

*Adapted Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale.Reference Herzog, Álvarez-Pasquin, Díaz, Del Barrio, Estrada and Gil23 HL = hearing loss; NR = not reported

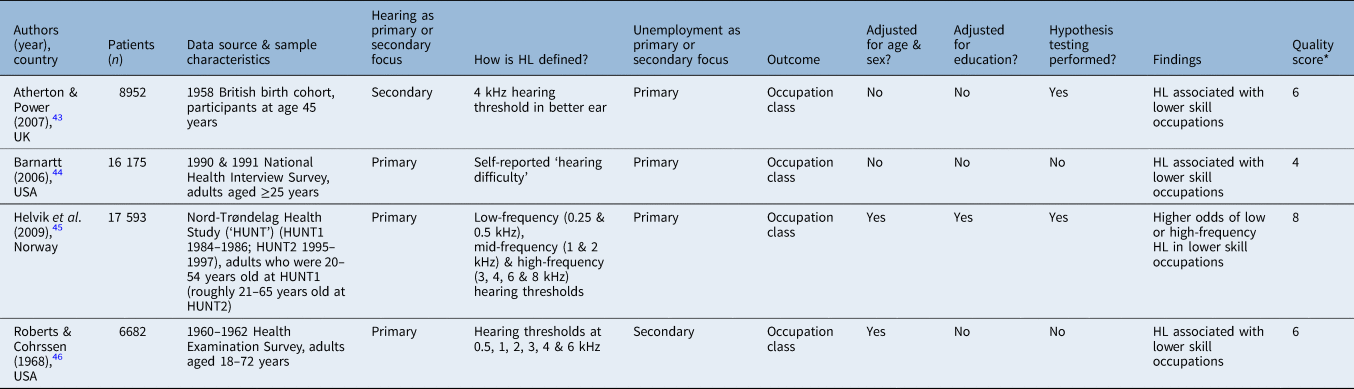

Table 3. Association between hearing loss and unemployment: studies investigating occupation class

*Adapted Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale.Reference Herzog, Álvarez-Pasquin, Díaz, Del Barrio, Estrada and Gil23 HL = hearing loss

Table 4. Association between hearing loss and unemployment: studies investigating disability pension or sick leave

*Adapted Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale.Reference Herzog, Álvarez-Pasquin, Díaz, Del Barrio, Estrada and Gil23 HL = hearing loss; VU = Vrije Universiteit

All 25 studies were cross-sectional. Twenty of the studies analysed large (n > 1000) population-based datasets, two were cohort studies and three were small scale (n < 1000) surveys. Of the included studies, 21 investigated work status (i.e. unemployment, underemployment, disability leave, sick leave), while 4 solely examined employment class (e.g. ‘blue collar’, ‘white collar’, etc.).

Study and definition variability

Articles featured data from a variety of countries, primarily high-income countries, with the USA being most common (n = 10), followed by the UK (n = 3), Australia (n = 3), Norway (n = 2), the Netherlands (n = 2), Sweden (n = 1), Spain (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), Japan (n = 1) and China (n = 1) (Tables 1–4). Sample size varied greatly, from 210 to over 187 million.

How studies defined hearing loss also varied: 8 used objective measures (7 used pure tone audiometry, 1 used speech-in-noise tests) and 13 used self-reports. The remaining studies employed other measures (e.g. International Classification of Diseases (‘ICD’) codes, patients of a hearing clinic, or individuals issued a hearing aid), or measures were not specified (n = 1). Among studies that utilised audiometric evaluations, hearing loss was defined differently: one studyReference He, Luo, Hu, Gong, Wen and Zheng24 used the 1991 World Health Organization definition of hearing loss (pure tone average threshold over 25 dB at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz in the better ear),47 and another studyReference Emmett and Francis25 used a similar definition over the same frequencies, but averaged over both ears; the remaining studies used pure tone averages as a continuous variable over a range of frequencies, mostly from 0.5 to 4 kHz, though some included 0.25 and 8 kHz. There was analogous variability in how self-reported hearing loss was defined, with some employing a Likert scale, and others using a binary question with variable language, such as hearing ‘disability’, ‘deaf or serious difficulty hearing’ or hearing ‘difficulty’.

Outcome measures demonstrated similar variability, with differing definitions of unemployment and underemployment, or other measures, such as occupational class. Unemployment definitions ranged from self-reported employment status, employment in the last week, or labour force status, while underemployment varied from less than 35 hours a week to part-time employment. Most studies that utilised occupational class stratified by higher to lower skill occupations, but the specific categories were inconsistent, with some using blue- or white-collar definitions and others separating into more specific occupation types.

Statistical methodology differed between studies, with several not performing formal hypothesis testing, and others performing multivariable analyses and adjusting for numerous variables. Most studies adjusted for age and sex in their models. Fewer studies also included variables such as education and race or ethnicity, which may influence employment status, and other indicators of socioeconomic status, such as income.

For sample demographics, most studies restricted the sample to ‘working-age adults’, though this definition also varied. The younger age cut-off ranged from 15 to 25 years old, while the older age cut-off ranged from 39 years to no restriction. Some studies did not specify an age range.

Hearing loss and unemployment

Overall, 21 out of 25 studies (84 per cent) examined the association between hearing loss and work status, through unemployment, underemployment or related measures (disability pension and sick leave). Out of these, 16 performed formal hypothesis testing, and 11 (69 per cent) of these reported significant differences in employment outcomes in individuals with hearing loss versus those without.

Studies that were most informative for determining an association between hearing loss and employment utilised nationally or regionally representative, population-based datasets. A total of seven such studies were identified.Reference He, Luo, Hu, Gong, Wen and Zheng24–Reference Helvik, Krokstad and Tambs26,Reference Brucker, Houtenville and Lauer28,Reference Jung and Bhattacharyya32,Reference Kim, Byrne and Parish33,Reference Chou, Beckles, Zhang and Saaddine39 These focused primarily on hearing loss and employment, adjusted for demographic factors including age, sex, education and other factors, and utilised formal hypothesis testing (Table 5). Six of the seven studies (86 per cent) reported significantly higher odds of unemployment or underemployment among individuals with hearing loss versus those with normal hearing. Though the number of high-quality studies was small, most reported an association between hearing loss and unemployment or underemployment.

Table 5. Summary of highest quality studies*

* Studies examining representative datasets, employment rates or other objective measures, and controlling for age, sex and education. †Unless indicated otherwise. HL = hearing loss; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; ICD9CODX = International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision code for condition

Hearing loss and employment class

Eight studies examined the association between hearing loss and employment class. Five of the eight studies (63 per cent) performed formal hypothesis testing, and all of these found associations between hearing loss and types of employment. The odds of lower occupation class, such as manual labour and blue-collar occupations, were increased in individuals with hearing loss compared to those without hearing loss.

Hearing loss and disability pension

One included study focused on the association between hearing loss and disability pension,Reference Helvik, Krokstad and Tambs26 and found a significant association between hearing loss and increased odds of disability pension use, despite controlling for age, sex and education status. Although our search strategy was not specifically designed to include studies on disability pension, it is a related outcome and the study met the inclusion criteria.

Discussion

Given the growing recognition of the potential impact of adult-onset and age-related hearing loss and an ageing global population, this systematic review aimed to summarise the current literature on the association between hearing loss and employment among adults. There was considerable variability in study design, definitions and statistical methodology, which was reflected in the range of adapted Newcastle-Ottawa Scores. Among the seven most rigorous studies, six demonstrated a significant association between hearing loss and employment, underemployment or disability pension. These data suggest that hearing loss impacts employment status, although the number of high-quality studies is small, and the association was not observed across all studies. In addition, these studies inconsistently controlled for other indicators of broader socioeconomic status. This is an important confounder, as socioeconomic status may be linked to both hearing loss (through environmental exposure, access to care, health behaviours, occupation type, etc.) and employment status.

Possible mediators of the association between hearing loss and employment were described in Kramer et al.,Reference Kramer, Kapteyn and Houtgast11 who surveyed workers with and without hearing loss, examining occupational performance and difficulties. These authors found that workers with hearing loss reported increased difficulty communicating in a noisy environment and localising and distinguishing sounds, accompanied by an increased self-reported listening effort. Individuals with hearing loss also reported decreased job control, consistent with prior literature.Reference Danermark and Gellerstedt48 These factors may contribute to the increased rates of stress-related sick leave observed.Reference Kramer, Kapteyn and Houtgast11 Other studies have also demonstrated increased prevalence of ‘occupational stress’ (i.e. risk of being moved to another job, fired or bankruptcy), burnout and social isolation among individuals with hearing difficulties.Reference Hasson, Theorell, Wallén, Leineweber and Canlon49,Reference Grimby and Ringdahl50 In addition, one survey found that individuals with hearing loss believed their hearing status made it harder for them to find employment, identifying a lack of support and employers’ attitudes toward hearing loss as barriers.51 All these factors may contribute to lower levels of employment among adults with hearing loss, although no causal relationship has been demonstrated.

All studies that investigated hearing loss and employment class reported an association. Hearing loss was associated with ‘blue-collar’ and ‘manual labour’ versus ‘managerial’ and ‘professional’ occupations. However, given the cross-sectional nature of these studies, causality and directionality cannot be determined, specifically whether hearing loss influenced the type of employment or if employment led to hearing loss. Both explanations are plausible, especially the latter given the risk of occupational noise exposure and associated noise-induced hearing loss.Reference Lie, Skogstad, Johannessen, Tynes, Mehlum and Nordby52 Blue-collar and lower class occupations have been demonstrated to be significantly associated with hearing loss in the past, presumably because of exposure to noise and/or ototoxic chemicals.Reference Agrawal, Platz and Niparko53,Reference Hong54

Although our literature search was not designed to include articles focused on disability pension, in one study, included based on search criteria, hearing loss was associated with an increased risk of disability pension. Of note, a systematic review specifically on hearing and otological diagnoses and their association with disability leave was conducted in 2012,Reference Friberg, Gustafsson and Alexanderson55 which found only two studies calculating rate or odds ratios of disability leave. Since then, another prospective cohort study was performed, which found an increased risk of disability leave among individuals with otological diagnoses in Sweden.Reference Friberg, Jansson, Mittendorfer-Rutz, Rosenhall and Alexanderson56 We acknowledge these findings, but do not make a conclusion on them as they were not the primary focus of this study.

Although we employed a systematic approach with a broad literature search across multiple databases, there are limitations to this systematic review. We may not have identified all articles related to hearing loss and employment, as several included studies did not focus primarily on hearing loss, employment or both. Our literature search found multiple studies that reported either rates of hearing loss or employment, but not as a primary focus, and did not include formal hypothesis testing. These findings are difficult to interpret, as re-analysis could not be performed without sample size information. In addition, these studies may have carried out testing that did not result in significant findings and subsequently were not published, highlighting the potential risk of publishing bias.

Another limitation of our study is the inability to distinguish between congenital and adult-onset hearing loss. All included studies focused on adults with hearing loss, specifically excluding those mentioning congenital loss. However, the precise aetiologies were not always uniformly indicated. Some of the studies may have included individuals with congenital hearing loss in their analytical cohort, though given the relatively low prevalence of congenital hearing loss compared to adult-onset or age-related hearing loss, we expect the impact of these individuals on our conclusions to be small.

Another important limitation is that all the included studies are cross-sectional, and the directionality of any potential association between hearing loss and employment cannot be determined. Finally, the reviewed studies included data from primarily high-income countries (9 out of 10), and do not provide insight into the potential impact of hearing loss among adults in middle-income and particularly low-income countries, and in emerging markets where employee protections and resources may be limited.Reference Lie, Skogstad, Johannessen, Tynes, Mehlum and Nordby52

Overall, relatively few studies have investigated the link between hearing loss in adults and employment, despite the prevalence and potential impact of adult-onset hearing loss on the health and wellbeing of individuals. Few studies controlled for important demographic factors, such as age, sex and education. However, several large, well-designed studies exist, and these suggest that hearing loss among adults is associated with unemployment.

With a rapidly ageing global population and workforce that is anticipated to be living primarily in low- and middle-income countries by 2050, more must be done to better define the impact of hearing loss, an increasingly common condition, on employment. The limitations identified in this systematic review call for dedicated efforts to understand mediators and potential interventions across diverse populations, including the experience of adults and older adults with hearing loss in low- and middle-income countries and markets, in order to meet the demands of the coming demographic shift of an ageing population.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported in part by a National Institute on Aging grant (number K23AG059900, awarded to author CLN). The funders had no role in interpreting the findings.

Competing interests

None declared

Appendix 1. Search strategies

PubMed

("employment"[mesh:noexp] OR employ*[tw] OR "unemployment"[mesh:noexp] OR unemploy*[tw] OR nonemploy*[tw] OR un employ*[tw] OR non employ*[tw] OR "work status"[tw])

AND

("hearing disorders"[mesh:noexp] OR "hearing loss"[mesh] OR "communication disorders"[mesh:noexp] OR "persons with hearing impairments"[mesh] OR "presbycusis"[mesh] OR "communication disorder"[tw] OR "communication disorders"[tw] OR "hard of hearing"[tw] OR "hearing disabled"[tw] OR "hearing disability"[tw] OR "hearing disorder"[tw] OR "hearing disorders"[tw]OR "hearing loss"[tw] OR "hearing losses"[tw] OR "hearing impaired"[tw] OR "hearing impairment"[tw] OR "hearing impairments"[tw] OR "hearing handicap"[tw] OR "hearing handicapped"[tw] OR presbycus*[tw] OR presbyacus*[tw] OR "hearing problem"[tw] OR "hearing problems"[tw])

Embase

('employment'/de OR employ*:ti,ab,kw OR 'unemployment'/de OR unemploy*:ti,ab,kw OR nonemploy*:ti,ab,kw OR 'un employ*':ti,ab,kw OR 'non employ*':ti,ab,kw OR 'work status':ti,ab,kw)

AND

('hearing disorder'/de OR 'hearing impairment'/de OR 'communication disorder'/de OR 'hearing impaired person'/de OR 'presbaycusis'/de OR 'communication disorder':ti,ab,kw OR 'communication disorders':ti,ab,kw OR 'hard of hearing':ti,ab,kw OR 'hearing disabled':ti,ab,kw OR 'hearing disability':ti,ab,kw OR 'hearing disorder':ti,ab,kw OR 'hearing disorders':ti,ab,kw OR 'hearing loss':ti,ab,kw OR 'hearing losses':ti,ab,kw OR 'hearing impaired':ti,ab,kw OR 'hearing impairment':ti,ab,kw OR 'hearing impairments':ti,ab,kw OR 'hearing handicap':ti,ab,kw OR 'hearing handicapped':ti,ab,kw OR presbycus*:ti,ab,kw OR presbyacus*:ti,ab,kw OR 'hearing problem':ti,ab,kw OR 'hearing problems':ti,ab,kw)

Cochrane Library

([mh ^"employment"] OR employ*:ti,ab,kw OR [mh ^"unemployment"] OR unemploy*:ti,ab,kw OR nonemploy*:ti,ab,kw OR un employ*:ti,ab,kw OR non employ*:ti,ab,kw OR "work status":ti,ab,kw)

AND

([mh ^"hearing disorders"] OR [mh ^"hearing loss"] OR [mh ^"communication disorders"] OR [mh "persons with hearing impairments"] OR [mh "presbycusis"] OR "communication disorder":ti,ab,kw OR "communication disorders":ti,ab,kw OR "hard of hearing":ti,ab,kw OR "hearing disabled":ti,ab,kw OR "hearing disability":ti,ab,kw OR "hearing disorder":ti,ab,kw OR "hearing disorders":ti,ab,kwOR "hearing loss":ti,ab,kw OR "hearing losses":ti,ab,kw OR "hearing impaired":ti,ab,kw OR "hearing impairment":ti,ab,kw OR "hearing impairments":ti,ab,kw OR "hearing handicap":ti,ab,kw OR "hearing handicapped":ti,ab,kw OR presbycus*:ti,ab,kw OR presbyacus*:ti,ab,kw OR "hearing problem":ti,ab,kw OR "hearing problems":ti,ab,kw)

ABI/Inform Collection

(MAINSUBJECT.EXACT("Employment") OR employ* OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT("Unemployment") OR unemploy* OR nonemploy* OR "un employ*" OR "non employ*" OR "work status")

AND

(MAINSUBJECT.EXACT("Hearing impairment") OR "hearing loss" OR "communication disorder" OR "communication disorders" OR "persons with hearing impairments" OR "presbycusis" OR "hard of hearing" OR "hearing disabled" OR "hearing disability" OR "hearing disorder" OR "hearing disorders" OR "hearing loss" OR "hearing losses" OR "hearing impaired" OR "hearing impairment" OR "hearing impairments" OR "hearing handicap" OR "hearing handicapped" OR presbycus* OR presbyacus* OR "hearing problem" OR "hearing problems")

Business Source Ultimate

(DE "employment" OR employ* OR DE "unemployment" OR unemploy* OR nonemploy* OR "un employ*" OR "non employ*" OR "work status")

AND

("communication disorder" OR "communication disorders" OR "hard of hearing" OR "hearing disabled" OR "hearing disability" OR "hearing disorder" OR "hearing disorders" OR "hearing loss" OR "hearing losses" OR "hearing impaired" OR "hearing impairment" OR "hearing impairments" OR "hearing handicap" OR "hearing handicapped" OR presbycus* OR presbyacus* OR "hearing problem" OR "hearing problems")

Web of Science

TS=("employment" OR employ* OR "unemployment" OR unemploy* OR nonemploy* OR "un employ*" OR "non employ*" OR "work status")

AND

TS=("hearing disorders" OR "hearing loss" OR "communication disorders" OR "persons with hearing impairments" OR "presbycusis" OR "communication disorder" OR "hard of hearing" OR "hearing disabled" OR "hearing disability" OR "hearing disorder" OR "hearing disorders" OR "hearing loss" OR "hearing losses" OR "hearing impaired" OR "hearing impairment" OR "hearing impairments" OR "hearing handicap" OR "hearing handicapped" OR presbycus* OR presbyacus* OR "hearing problem" OR "hearing problems")

Scopus

TITLE-ABS-KEY("employment" OR employ* OR "unemployment" OR unemploy* OR nonemploy* OR "un employ*" OR "non employ*" OR "work status")

AND

TITLE-ABS-KEY("hearing disorders" OR "hearing loss" OR "communication disorders" OR "persons with hearing impairments" OR "presbycusis" OR "communication disorder" OR "hard of hearing" OR "hearing disabled" OR "hearing disability" OR "hearing disorder" OR "hearing disorders" OR "hearing loss" OR "hearing losses" OR "hearing impaired" OR "hearing impairment" OR "hearing impairments" OR "hearing handicap" OR "hearing handicapped" OR presbycus* OR presbyacus* OR "hearing problem" OR "hearing problems")