Introduction

Fungal diseases of the paranasal sinuses can be categorised into invasive and non-invasive varieties. Mucormycosis is an example of the invasive type.Reference Fatterpekar, Mukherji, Arbealez, Maheshwari and Castillo1

Phycomycoses are a diverse group of mycoses caused by fungi. The two major associated conditions are rhinophycomycoses (i.e. involving only the nose) and the rhino-cerebral type (also called mucormycosis). The second condition may be lethal. It is caused by circinelloides and Mucor javanicus, of the Mucoraceae family. These are ordinary saprophytic organisms existing in the soil, manure, fruits and starchy foods, which may be cultured from the human nose and gastrointestinal tract.Reference Fatterpekar, Mukherji, Arbealez, Maheshwari and Castillo1–Reference Kleinman, Bruce and William3

The organism becomes pathogenic when a patient's general resistance has been altered by metabolic disorders such as diabetic ketoacidosis and uraemia, leukaemia, or by immune suppression via drugs such as steroids, cytotoxics and antibiotics.Reference Fatterpekar, Mukherji, Arbealez, Maheshwari and Castillo1–Reference Peterson, Wang, Canalis and Abemayor10

Pathologically, the fungus has a remarkable affinity for arteries. It dissects the internal elastic lamina from the media, resulting in extensive endothelial damage and thrombosis. The histopathological picture is one of acute inflammation and necrotic changes.Reference Kleinman, Bruce and William3, Reference Macsween, Whaley, Sir Robert, MacSween, Roderick and Keith4

In the orbit and central nervous system, mucormycosis is the common type of phycomycosis encountered. Mucormycosis is usually commenced in the nose and by direct extension it will involve the Para nasal sinuses, orbit, cribriform plate, meanings and brain. It rarely invades the hard palate. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, and the lesion is treated by: controlling the underlying cause; systemic amphotericin; and local drainage and debridement. The prolonged use of potassium iodide is controversial. In skull base lesion combined treatment is indicated and even endovascular therapy with sacrificing involved carotid artery.Reference Fatterpekar, Mukherji, Arbealez, Maheshwari and Castillo1–Reference Alleyne, Vishtch and Spetzler5

Patients and methods

This was a prospective, clinical analysis of four cases of hard palate mucormycosis. The patients were admitted to the surgical department of the Basra teaching hospital between 1999 and 2006. During that time, eight patients with sino-nasal mucormycosis were managed. Their clinical details are shown in Table I.

Table I patients' clinical details

Pt no=patient number; M=male; F=female

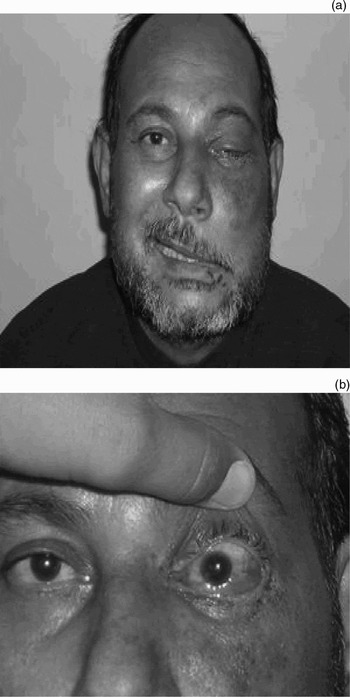

All patients were referred from the medical department, with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus with or without ketoacidosis. Blood stained nasal discharge, and facial swelling was the early sign of the disease (Figure 2). Four patients developed palate lesion during the course of treatment, but it was the presenting symptom in one occasion. Painful swelling, small ulcer filled with cheesy offensive material and large perforation was the actual clinical course of the disease (Figure 3, 4, 5).

The main methods of diagnosis were fungal study of antral sinus aspirate and tissue biopsy. Histological analysis revealed fungi with non-septated hyphae and right-angled branching, characteristic of mucormycosis. The primary focus of the lesion and the extension to the nearby structures was clearly detected by CT scan and or MRI views. There was a clear bony defect in the palate (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 Computed tomography scans showing extensive rhino-orbital soft tissue lesion. The affected eye is proptosed and destructed.

Fig. 2 (a) Facial swelling and (b) blind eye.

Fig. 3 Early hard palate ulceration.

Fig. 4 Extensive hard palate ulceration.

Fig. 5 Perforation of the hemi-palate.

Treatment consisted of antifungal drugs: amphotericin B via intravenous infusion for 10 days, followed by ketaconazole tablets, 200 mg twice daily orally, for life. Frequent, thorough debridement of the blackened dead spots in the nose and sinuses was the main surgical option. Diabetes control and heparinisation were important additional measures. Patient number six underwent excision of a frontal lobe fungal abscess, and went on to develop osteomyelitis of the frontal bone, with a discharging sinus.

Flexible nasendoscopy and radiological study (CT and MRI) were the procedures of choice for patients' follow up (Figure 1).

Results

Out of eight patients managed during the study period, four cases showed a defect in the hard palate; this was the second commonest site after the orbit. The lesions were mostly left-sided and were deep-seated and progressive (Figures 3, 4 and 5). There were three men and one woman, aged from 40 to 75 years. The disease was aggressive and almost always preceded by involvement of the orbit and intracranial cavity.

Unfortunately, the orbit was involved in all cases. There was perceptual visual loss in the left eye, ophthalmoplagia, dry eye and proptosis.

The brain and the skull base were involved in all instances. The most common findings on MRI and CT scanning were brain abscess with a clear cut wall, diffuse encephalitis and erosion of the skull base.

Two patients died after a short period of treatment. The radiological examination showed destruction and erosion at the bony fringe and spread to the adjacent areas.

Discussion

Hard palate mucormycosis is a sign of aggressive disease and indicates a rapid spread from the nasal cavity. In the above group of patients, the history of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and ketoacidosis was the underlying cause of reduced resistance to infection. All published studies have reported that the disease occurs in patients with malnutrition, neutropenia, ketoacidosis, and immunosuppression due to drugs (including cytotoxics) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.Reference Fatterpekar, Mukherji, Arbealez, Maheshwari and Castillo1–Reference Peterson, Wang, Canalis and Abemayor10

All published reports of mucormycosis state that the involvement of the hemi-palate is uncommon, being rarely recorded in cases of rhino-cerebral mucormycosis. However, the above four cases showed definite involvement of the hemi-palate, either at the time of presentation or during the course of treatment. A painful, ulcerative spot gradually appeared on the hard palate, on the same side as the nasal lesion. Within days, true perforation of the palate was seen, accompanied by profuse, foul smelling discharge and radiological evidence of bony erosion. This was the result of the ischaemia and necrosis caused by fungal invasion of blood vessels.Reference Lerchenmuller, Goner, Buchner and Berdel6, Reference Gupta, Mann, Khosla, Sastry and Hundal9

Once a red swelling was discovered on the palate, the patient was thoroughly assessed for intracranial extensions. In the above patients, cerebral lesions and orbital destruction were reported in all instances. Gupta et al. has stated that palatal perforation is only seen in severe cases of sino-nasal fungal infection, and requires correction with a dental plate.Reference Lerchenmuller, Goner, Buchner and Berdel6, Reference Gupta, Mann, Khosla, Sastry and Hundal9

In all instances, the early signs of the disease were orbital. Vision gradually diminished, with progression to total blindness. All previous authors have reported a high incidence of orbital extension.Reference Alleyne, Vishtch and Spetzler5, Reference Sykes and Sukha8

The prognosis of the condition is poor; two cases in the present series died, and the others had intracranial spread. In addition, the involvement of the orbit was a bad prognostic sign, as mentioned in all previous reports, as it indicates central nervous system extension of the disease.

The diagnosis was confirmed by culture of maxillary antrum aspirate, facial abscess pus or purulent discharge from the palatal ulcer. However, tissue biopsy is the cornerstone of definitive diagnosis, allowing differentiation from other sino-nasal granulomatous conditions and tumours, as mentioned by Sykes et al. Reference Fatterpekar, Mukherji, Arbealez, Maheshwari and Castillo1, Reference Gupta, Mann, Khosla, Sastry and Hundal9, Reference Peterson, Wang, Canalis and Abemayor10

The treatment used was the same as for any case of sino-nasal mucormycosis. Antifungal drugs comprise the basic regimen, in the form of amphotericin infusion in the acute phase, followed by long term ketaconazole tablets. This was accompanied by frequent surgical debridement and drainage. Reports in the literature give no clear information about prolonged use of antifungal drugs or patient follow up protocols.

Conclusion

Invasion of the hard palate is a rare complication of overwhelming fungal infection of the nose and paranasal sinuses. It is a poor prognostic sign and is usually preceded by orbital and even cerebral extension. Clinicians should maintain a high degree of clinical suspicion in the management of patients with debilitating illness and ulceration of the palate.

• Mucormycosis is an opportunistic, fulminating fungal infection of the sino-nasal region, occurring predominantly in patients with immune suppression

• The hard palate is a rare site of the disease, and few cases have been reported in the literature

• Hard palate involvement in mucormycosis is a sign of poor prognosis and is usually preceded by orbital and intracranial extension

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Jasim M Diab, Pathologist, Basra Medical College, and Ebtehal Y Abdalsammad, Ophthalmological Specialist, Al-Mawany Hospital, for their help and cooperation.