Introduction

The frontal sinuses are mucosa-lined airspaces within the bones of the face and skull. They are rarely symmetrical, and the septum between them frequently deviates to one or the other side of the midline.Reference Lee, Sakai and Spiegel1 The frontal sinuses open into the anterior part of the corresponding middle nasal meatus of the nose through the frontonasal duct, which traverses the anterior part of the labyrinth of the ethmoid.

Several anatomical variations of the frontal sinus structure have been previously reported. The most frequently discussed are the frontal cells.Reference Bent, Cuilty-Siller and Kuhn2 Several other anatomical variants have been described, including the hyperpneumatised frontal sinus, hypopneumatised frontal sinus, pneumatised crista gall and intersinus septal cell. The importance of these reported frontal sinus variations are their clinical implications, as many of these anatomical variants might increase the rates of recurrent or chronic rhinosinusitis, and should be addressed during surgical intervention. These variants also have surgical implications, as they might change the surgical technique or serve as a venue to treat the pathology.Reference McLaughlin, Hwang and Lanza3

An understanding of the anatomical correlation between the frontal sinuses and the upper part of the nasal septum might be crucial for the endoscopic surgeon. The abovementioned variants should be thoroughly studied by the surgeon for better post-operative results. The question raised is whether all frontal sinus anatomical variants have been addressed.

This study aimed to describe a newly observed frontal sinus anatomical variant: the fronto-septal rostrum. In this variant, the invagination process of the frontal sinuses is suspected to involve the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone, which is the most superior bony nasal septum. Herein, we estimate fronto-septal rostrum prevalence, suggest a method of classification and discuss possible clinical implications.

Materials and methods

The study was approved by the Asaf Harofe Medical Center Review Board.

A total of 400 consecutive sinus computed tomography (CT) scans, from patients of all ages including children, which were performed between January and December 2013, were reviewed using our institute's Picture Archiving and Communications System.

We reviewed sinus CT scans performed for sinus pathology. Only the CT scans with contiguous axial cuts of 1–1.5 mm thickness were included in the survey. The data were then reconstructed into coronal and sagittal images by a computer. Exclusion criteria included: a history of prior sinus surgery, trauma or tumour.

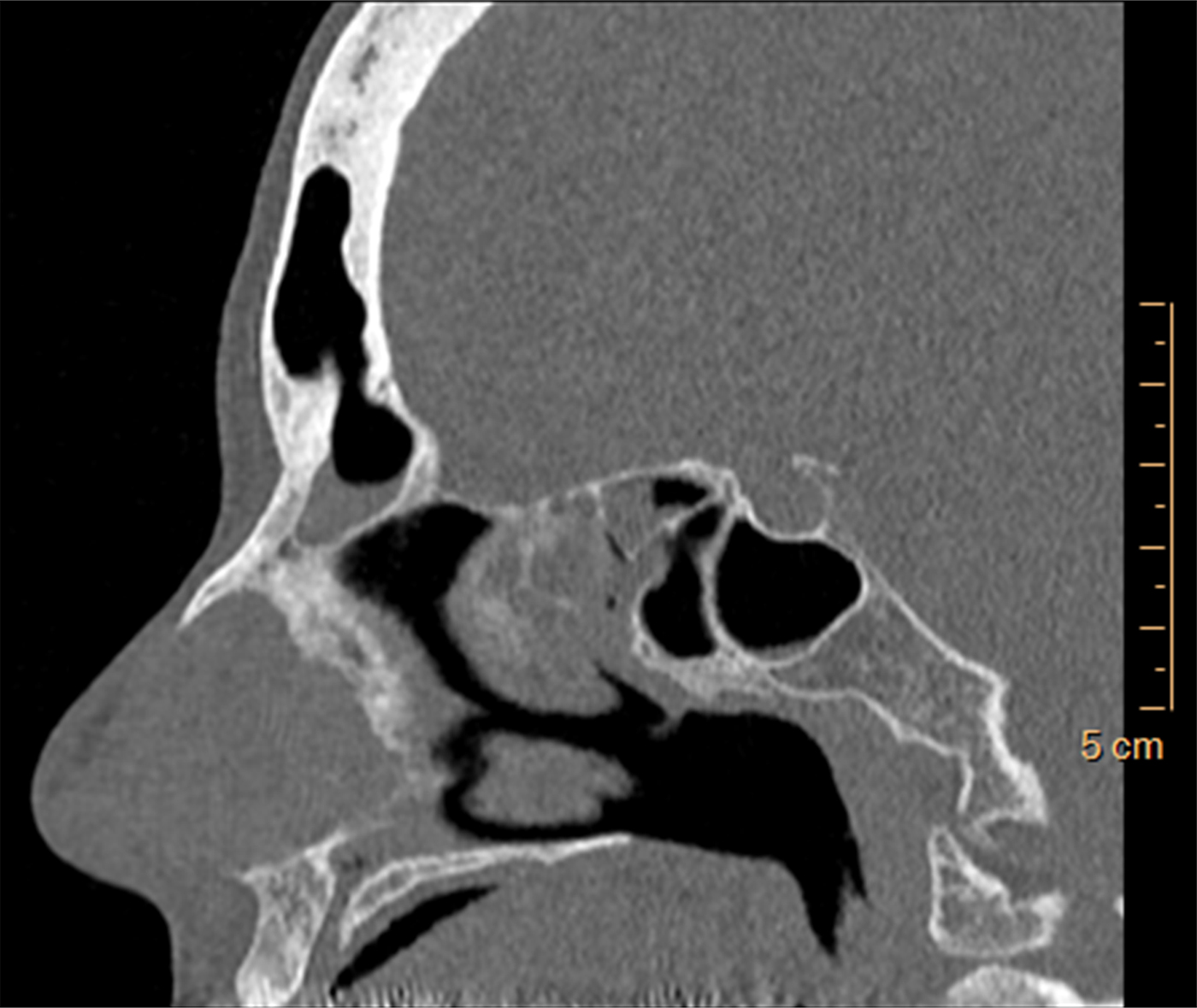

The presence of a fronto-septal rostrum was determined by the authors based on the observation of a mucosa-lined air space formed in the attachment of the most upper bony nasal septum and the central floor of the frontal sinuses (Figures 1 and 2). This bony septal pneumatisation is funnel shaped and variable in size, resembling the attachment between the sphenoid sinuses and the nasal septum, known as the ‘rostrum’.

Fig. 1 A fronto-septal rostrum as seen on a coronal computed tomography scan. P = posterior; F = feet

Fig. 2 A fronto-septal rostrum as seen on a sagittal computed tomography scan.

All of the CT scans were evaluated to calculate the dimensions of the fronto-septal rostrum. These dimensions were taken by measuring the longest uninterrupted straight lines that could be drawn in the anterior–posterior (Figure 3), medial–lateral (Figure 4) and superior–inferior (Figure 5) dimensions. The fronto-septal rostrum volume was calculated as a prism, as this was the closest configuration to the anatomical shape of the fronto-septal rostrum.

Fig. 3 The fronto-septal rostrum dimensions measuring the longest uninterrupted straight line in the anterior–posterior dimension.

Fig. 4 The fronto-septal rostrum dimensions measuring the longest uninterrupted straight line in the medial–lateral dimension. P = posterior; F = feet

Fig. 5 The fronto-septal rostrum dimensions measuring the longest uninterrupted straight line in the superior–inferior dimension. P = posterior; F = feet

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are reported as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables are reported as medians and interquartile ranges. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney or Kruskal Wallis test. Spearman's rank correlation co-efficient was used to evaluate the association between volume and age. A two-tailed p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 3.3.1).4

Results

The patient population consisted of 189 women (47.3 per cent) and 211 men (52.8 per cent), with a mean age of 46.8 years. A fronto-septal rostrum was observed in 122 patients (30.5 per cent). The rest had a simple unaerated connection between the nasal septum and the floor of the frontal sinuses.

The fronto-septal rostrum mean antero-posterior length was 10.63 mm (range, 3–22 mm), mean coronal width was 4.52 mm (range, 1.9–11 mm) and mean height was 2.18 mm (range, 0.8–6 mm). The mean fronto-septal rostrum volume was 63.52 mm3, with a wide range of 8.8–353.1 mm3.

The measures showed no statistically significant difference in relation to gender in all analysed parameters (p = 0.343), including length, width, height and volume, signifying that all sizes were located in both men and women (Table I).

Table I Prevalence of fronto-septal rostrum according to gender and age

*n = 400; †n = 278; ‡n = 122. IQR = interquartile range

In our cohort, only 19 children under the age of 18 years underwent sinus CT, with a median age of 15 years (range, 7–17 years) (Table II). Although the children in our cohort are not equally represented because of the conventional avoidance of performing CT scans in children, the age of patients in the fronto-septal rostrum group was not statistically different from the age in the non-fronto-septal rostrum group (p = 0.458) (Table I). Four children between the ages of 10 and 18 years were observed to have a fronto-septal rostrum.

Table II Characteristics of children* in our cohort who underwent computed tomography

*Aged less than 18 years. †Only 4 of the 19 children were observed to have a fronto-septal rostrum.

The fronto-septal rostrum was found on the right side in 55 cases (45 per cent) and on the left in 58 (47.5 per cent). A bilateral fronto-septal rostrum was found in nine cases (7.37 per cent). Again, no statistically significant difference in the side of the fronto-septal rostrum was observed in relation to gender (p = 0.346) (Table III). In addition, no association was found between the side of the fronto-septal rostrum and the patient's age (p = 0.811) or volume of the fronto-septal rostrum (p = 0.203) (Table III).

Table III Location of fronto-septal rostrum according to gender, age and size

*n = 278; †n = 55; ‡n = 58; **n = 9. IQR = interquartile range; N/A = not applicable

Discussion

In general, frontal cells are ethmoid-type cells that have pneumatised the frontal bone (i.e. extramural ethmoid cells). The frontal sinuses possess a complex and inconstant anatomy. Variable anatomical variations of the frontal sinus structure have even been utilised for the purposes of forensic identification of unknown deceased persons.Reference Nambiar, Naidu and Subramaniam5 These anatomical variations are the cause of some frontal sinus pathologies and the reason for difficulties arising in surgical management of the frontal sinuses.Reference Langille, Walters, Dziegielewski, Kotylak and Wright6

The clinical significance of the fronto-septal rostrum is not apparent in most nasal pathologies. Two case reports have been published in the last several years describing a rare entity referred to as a septal abscess. In these two reported cases, the aetiology of the abscess was not revealed as the result of any trauma or nasal cavity infection.Reference Wang, Zou, Han and Zhang7, Reference Lin and Huang8 Wang et al. reported on a Chinese case of a fronto-septal rostrum mucocele, and described CT scans showing anatomical features of aeration of the perpendicular plate in 2 out of 32 cases, with no further details regarding the dimensions of this variation.Reference Wang, Zou, Han and Zhang7

We came across a patient with a recurrent formation of a nasal septum abscess that originated from an infected frontal sinus, which resolved after a Draf IIB endoscopic frontal sinusotomy procedure. Hence, it was actually an infected fronto-septal rostrum. As drainage at this location might be difficult, especially in a fronto-septal rostrum with a greater height (Figure 6), we assume that a patient with a fronto-septal rostrum may be more prone to developing a septal abscess resulting from an infected fronto-septal rostrum than those who do not have a fronto-septal rostrum. Management of this rare pathology should include wide drainage of the frontal sinus, with simultaneous drainage of the septal abscess. In our case of an infected fronto-septal rostrum, an endoscopic transnasal approach was possible, with complete cure and no recurrence after 15 years of follow up.

• Several anatomical variations of frontal sinus structure have been reported, including frequently discussed frontal cells

• These frontal sinus variations have clinical implications that should be addressed during surgical intervention

• A newly observed frontal sinus anatomical variant, the fronto-septal rostrum, is described

• This is an invagination process of frontal sinuses involving the ethmoid bone perpendicular plate

• A fronto-septal rostrum was observed in 30.5 per cent of the cohort patients

• It is suggested that this aerated space is used in specific surgical indications and its presence evaluated in peculiar septal infection cases

Fig. 6 A long superior–inferior dimension fronto-septal rostrum probably prone to infections. R = right

Possible surgical benefits of the fronto-septal rostrum should be further discussed. Approaching the frontal sinus and performing advanced Draf procedures might require drilling the frontal beak. This hard bone usually obscures the frontal recess, and drilling it away usually aids in the wide opening of the frontal sinus. This bony component's medial border is the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone. If the frontal beak is aerated as an anterior extension of a fronto-septal rostrum (Figure 7), less bone needs to be drilled away and an easier procedure can be expected by the surgeon. This is to be anticipated in the widest and most anterior fronto-septal rostrum. Although performing a Draf III procedure is widely accepted in cases of a failed Draf IIB procedure, we routinely perform an extended Draf IIB procedure, during which removal of the nasal septum in its attachment to the frontal floor is performed, gaining more space for the drainage of the unilateral frontal sinus. In cases of a fronto-septal rostrum, the space is larger, and the need for a Draf III procedure is removed.

Fig. 7 An aerated frontal beak as is observed in an anterior extension of a fronto-septal rostrum.

McLaughlin et al. described transseptal frontal sinusotomy in which the septum is translocated to achieve the frontal sinus ostium.Reference McLaughlin, Hwang and Lanza3 In the presence of a fronto-septal rostrum, this approach is also expected to be easier. Recently, the crista galli structure has drawn attention, as its dimensions are significant in planning endoscopic anterior skull base surgery.Reference Lee, Ransom, Lee, Palmer and Chiu9 We would suggest utilising the transseptal approach while widening the fronto-septal rostrum for better infero-anterior exposure of the crista galli when employing this innovative approach (Figure 8).

Fig. 8 A fronto-septal rostrum in continuum with aerated crista galli.

No gender differences were found in our study. In a recent article measuring frontal sinus dimensions according to gender, the overall width and height of the frontal sinus was generally not greater in males compared to females.Reference Verma, Mahima and Patil10 However, statistically significant gender variations were found at or close to the midline, in the area identified as the glabella.Reference Lee, Sakai and Spiegel1, Reference Verma, Mahima and Patil10 Here, males clearly possessed more prominent forehead features, as measured by the greater thickness of the anterior table, deeper anterior–posterior dimensions and greater overall width of the glabella.Reference Lee, Sakai and Spiegel1 Despite these features, fronto-septal rostrums had similar features in males and females.

Based on the aforementioned clinical cases, we suggest classifying the fronto-septal rostrum as deep, anterior or posterior (Figure 9a represents normal anatomy). A deeper fronto-septal rostrum probably has a higher risk of presenting as a septal abscess when infected (Figure 9b). The more anterior fronto-septal rostrum thins the anterior frontal bone and frontal beak, thereby easing advanced Draf procedures and the anterior transseptal approach (Figure 9c). The posterior fronto-septal rostrum includes the combination of a fronto-septal rostrum and crista galli aeration (Figure 9d).

Fig. 9 Fronto-septal rostrum classification: (a) normal anatomy, (b) inferior subtype, (c) anterior subtype and (d) posterior subtype.

A medial–lateral sub-classification to a thinner or a wider fronto-septal rostrum is suggested; the latter will be of more beneficial significance in the various transseptal approaches.

There are two major limitations to our study. The current study population comprised patients with sinus complaints referred to a tertiary care centre for a CT scan, and thus is likely not to be reflective of the general population. Secondly, the clinical significance of the fronto-septal rostrum and the classification provided are not based on experience obtained, as the number of patients in which the fronto-septal rostrum has an unproven importance is small. Further studies are needed to support our ideas.

Conclusion

The newly described fronto-septal rostrum is a common unnoticed anatomical variation, with possible clinical and surgical implications that need further careful evaluation. We suggest using this aerated space in specific surgical indications and evaluating its presence in cases with peculiar septal infections.