Introduction

A range of surgical approaches to the maxillary sinus can be considered in the treatment of inflammatory or neoplastic rhinological disease. Historically, the maxillary sinus was accessed by external approaches such as lateral rhinotomy, even in cases of benign disease. The endoscopic approach has now replaced external approaches as the standard of care, because of the reduced morbidity, improved visualisation and lower recurrence rates of benign tumours.Reference Goudakos, Blioskas, Nikolaou, Vlachtsis, Karkos and Markou1 However, standard middle meatal antrostomy offers limited access to the maxillary sinus.

In cases where the disease is extensive, originates from the anterior wall, or involves the pterygopalatine or infratemporal fossa, a range of extended endoscopic approaches are available to allow improved access of both endoscopes and instruments. These are listed in Table 1 alongside the traditional external and open approaches. This review aimed to discuss the benefits and drawbacks of each of the endoscopic modalities available to the modern rhinologist.

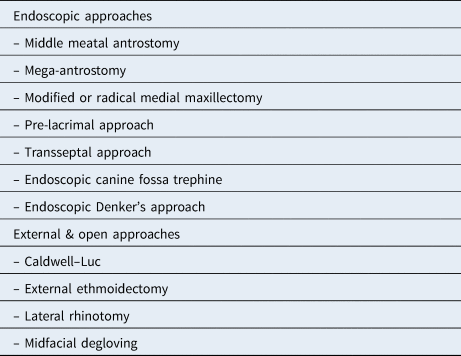

Table 1. Endoscopic, and external or open approaches to maxillary sinus

Materials and methods

A literature search of the Ovid Medline and PubMed databases was performed using appropriate key words relating to endoscopic approaches to the maxillary sinus. Relevant case series, and cadaveric, imaging and interventional studies, were identified and reviewed for relevance.

Anatomy

The largest of the paranasal sinuses, the maxillary sinus, has a final volume of around 10 ml.Reference Wagenmann and Naclerio2 It is the first sinus to develop embryologically, starting at the 10th week, and is almost always present at birth.Reference Nunez-Castruita, Lopez-Serna and Guzman-Lopez3 Subsequent pneumatisation occurs as the facial skeleton grows and matures, with the sinus reaching 25 per cent of its final size by age 2 years, up to 50 per cent by age 8 years, and by the 16th year the sinus will have reached its final adult size.Reference Lorkiewicz-Muszynska, Kociemba, Rewekant, Sroka, Jonczyk-Potoczna and Patelska-Banaszewska4

The sinuses are pyramidal voids within the maxilla, the base being the lateral border of the nasal cavity and the apex lying towards the zygomatic process. The roof of the sinus forms the orbital floor, and the base of the sinus may extend into the alveolar part of the maxilla to the extent that dental roots may project into the sinus.

Drainage

Drainage is via the natural ostium in the superomedial part of the sinus that opens into the hiatus semilunaris, posterior to the uncinate process. The cilia lining the mucosa beat towards the natural ostium, and thus clear maxillary secretions out of the sinus through this mechanism.Reference Gosau, Rink, Driemel and Draenert5

Accessory ostia are present in around one-fifth of patients, and are associated with a higher likelihood of mucosal disease, recurrent acute sinusitis and retention cysts.Reference Yenigun, Fazliogullari, Gun, Uysal, Nayman and Karabulut6 At surgery, an accessory ostium may be mistaken for the natural ostium, leading to the ‘missed ostium’ sequence whereby the natural ostium remains obstructed by the uncinate and is not included within the antrostomy.Reference Parsons, Stivers and Talbot7 This may have the functional effect known as mucus circulation, whereby secretions cleared via the natural ostium are drawn back into the sinus through the accessory ostium, thus contributing to rhinorrhoea and post-nasal drip.

Indications for surgery

Inflammatory disease of the maxillary sinus may occur in the context of allergic or infective rhinosinusitis, with or without the formation of inflammatory polyps. Unilateral maxillary disease is often related to odontogenic causes such as periapical abscesses of the upper molars.Reference Little, Long, Loehrl and Poetker8 When such cases fail to respond to maximal medical therapy, uncinectomy and middle meatal antrostomy is performed to ventilate the sinus, reduce the inflammatory burden by removal of polyps and debris, and, possibly most importantly, improve access for topical medications.

Benign, pre-malignant and malignant neoplasms of the maxillary sinus may be amenable to endoscopic resection. Inverted papilloma is the most common benign neoplasm of the sinonasal cavity; it is managed by meticulous surgical resection because of its risk of malignant transformation, its locally invasive nature and its tendency to recur. Malignant neoplasms of the paranasal sinuses can originate from or involve the maxillary sinus, and thus suitable access must be offered to allow for an appropriate oncological resection. Finally, lesions involving the pterygopalatine and infratemporal fossae may be approached endoscopically through the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, requiring extended endoscopic approaches.

Uncinectomy and middle meatal antrostomy

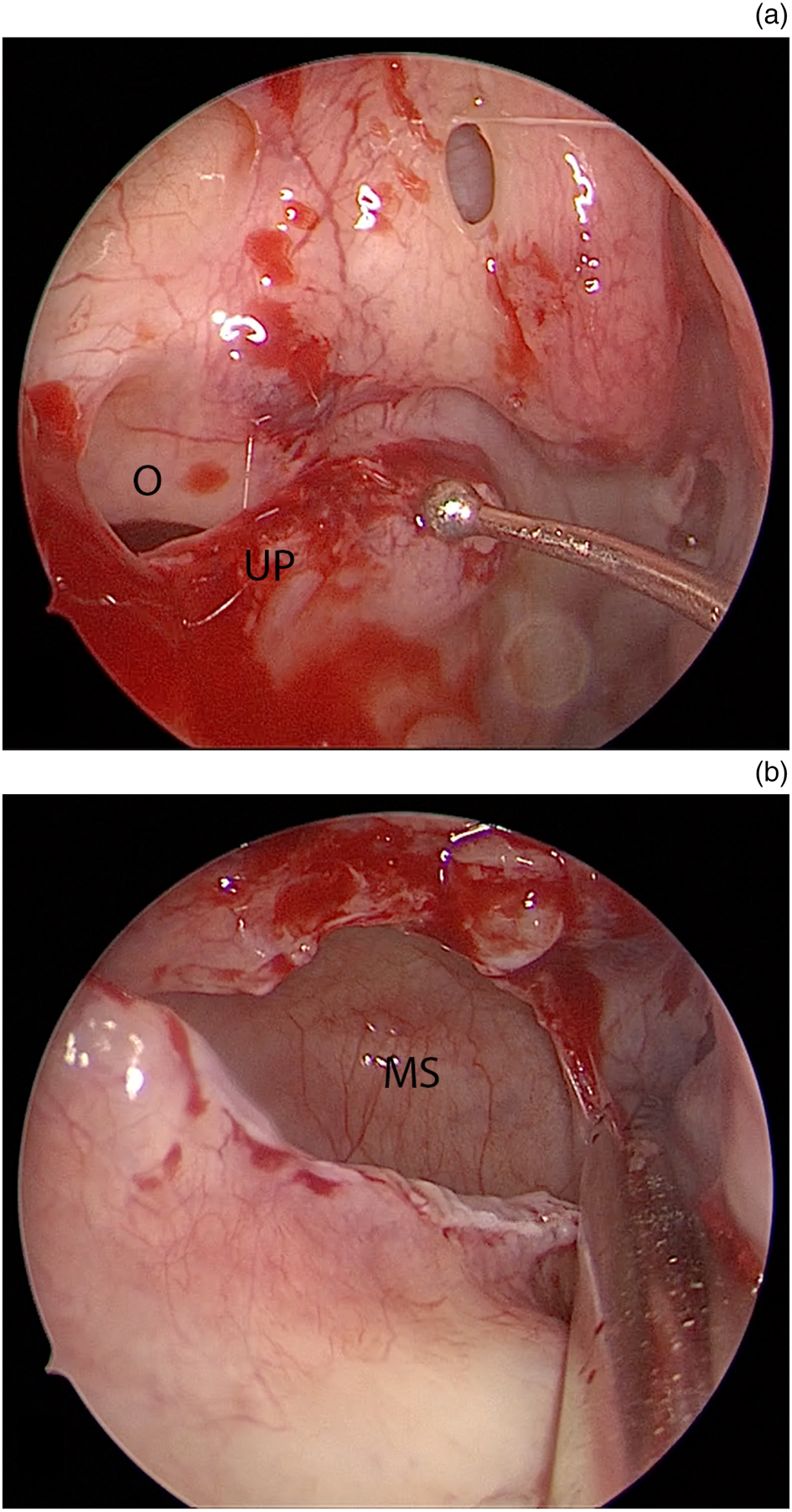

At endoscopic sinus surgery, the maxillary sinus is commonly accessed via an uncinectomy and middle meatal antrostomy (Figure 1 and Table 2). However, this allows only limited access to the sinus. A 2010 study using cadaveric heads found that a middle meatal antrostomy only provided access to 24–34 per cent of the total sinus volume, and rarely offered access to the anterior wall and sinus floor, regardless of the angled instruments used.Reference Robey, O'Brien and Leopold9 This approach is adequate to drain mucopus and treat minor inflammatory disease or postero-medially based tumours; however, it is not always adequate for more significant disease.

Fig. 1. Endoscopic images of middle meatal antrostomy. (a) Natural ostium (O) and inferior uncinate process (UP). (b) Widened middle meatal antrostomy demonstrating access to superior maxillary sinus (MS) only.

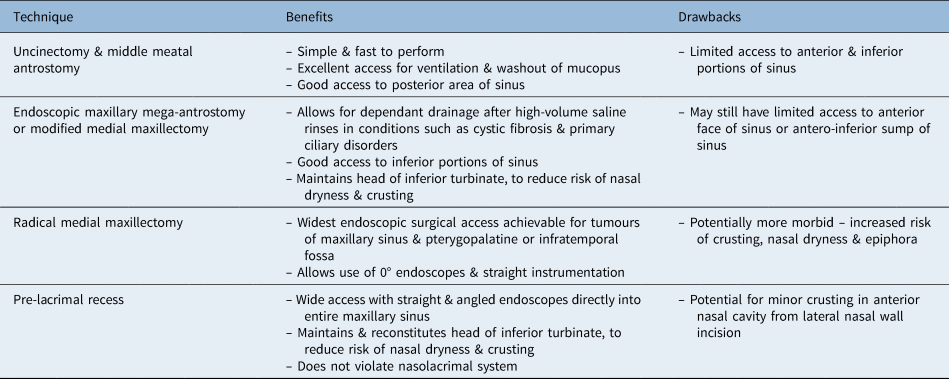

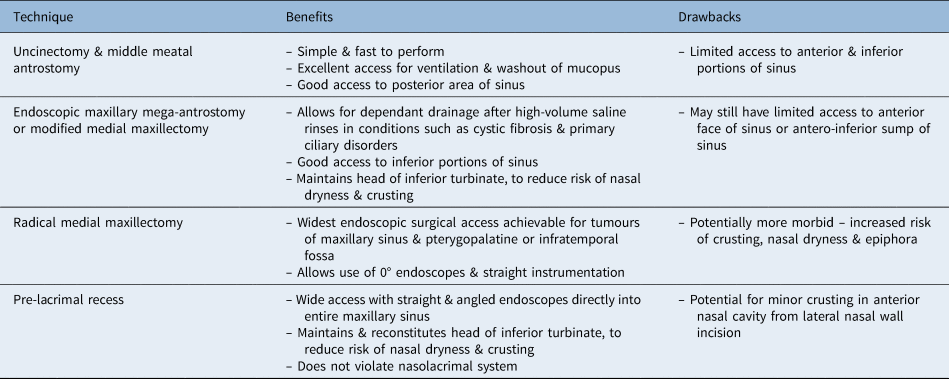

Table 2. Pros and cons of endoscopic techniques to access maxillary sinus

Endoscopic maxillary mega-antrostomy

Endoscopic maxillary mega-antrostomy is typically used as a revision procedure in patients with maxillary sinusitis refractory to surgery.Reference Cho and Hwang10,Reference Woodworth, Parker and Schlosser11 After a standard middle meatal antrostomy, the antrostomy is extended posteriorly to the back wall of the sinus and inferiorly to the level of the nasal floor, thereby requiring a posterior partial inferior turbinectomy (Figure 2). The resulting antrostomy is greatly enlarged and allows the sinus to drain more easily by gravity, as well as admitting topical therapy more readily (Table 2). This is potentially useful in patients with impaired mucociliary clearance such as cystic fibrosis or primary ciliary dyskinesia,Reference Thompson and Conley12 as well as in cases where there is a high inflammatory burden in the maxillary sinus such as severe polyposis or fungal sinusitis.

Fig. 2. Endoscopic images of maxillary mega-antrostomy. (a) Sharp resection of mid-portion of inferior turbinate (IT). (b) Exposed inferior meatus. (c) Mucosal flap (MF) medialised to expose bone of inferior meatus. (d) View into maxillary sinus following bony removal. MT = middle turbinate

Inadequate resection of fungal debris or polyps, especially in areas typically inaccessible through a standard middle meatal antrostomy such as the pre-lacrimal recess, will leave residual pro-inflammatory material and may be a cause of surgical failure.Reference Bassiouni, Naidoo and Wormald13

Costa et al. published the long-term outcomes for a cohort of 122 patients.Reference Costa, Psaltis, Nayak and Hwang14 The authors reported that all patients with recalcitrant maxillary sinusitis experienced symptomatic improvement, with almost 75 per cent describing complete symptom resolution, with no late complications.

Endoscopic medial maxillectomy

In its radical form, endoscopic medial maxillectomy involves the removal of the entire inferior turbinate, uncinate process, ethmoid bulla, and the medial maxillary wall containing the distal portion of the nasolacrimal duct (Figure 3). Radical endoscopic medial maxillectomy is indicated for the resection of benign and malignant sinonasal neoplasms where wide surgical access and tumour clearance is required (Table 2).Reference Sadeghi, Al-Dhahri and Manoukian15–Reference Luong, Citardi and Batra17 However, resection of the inferior turbinate head may contribute to nasal crusting, dryness and empty nose syndrome.Reference Kastl, Rettinger and Keck18,Reference Dayal, Rhee and Garcia19

Fig. 3. Endoscopic images of radical medial maxillectomy. (a) Frontal process of maxilla (FP) exposed and prepared for osteotomies. (b) Lacrimal sac (LS) exposed with sharp transection. (c) View into maxillary sinus, demonstrating multifocal inverted papilloma (IP) with anterior and superior attachments. (d) Wide surgical access to entire maxillary sinus following tumour resection.

The modified endoscopic medial maxillectomy can be considered akin to endoscopic maxillary mega-antrostomy, in which the head of the inferior turbinate and nasolacrimal duct are preserved (Figure 4), but with additional bone of the inferomedial maxillary wall resected. Its use has been described in treating refractory sinus disease.Reference Durr and Goldberg20 Furthermore, similar to endoscopic maxillary mega-antrostomy, modified endoscopic medial maxillectomy gives superior access to the maxillary sinus (compared to middle meatal antrostomy), whilst preserving the head of the inferior turbinate. This maintains the humidification function of the inferior turbinate, resulting in less crusting when compared to radical endoscopic medial maxillectomy.Reference Kastl, Rettinger and Keck18 Several authors have described modifications of this technique in an attempt to preserve even more inferior turbinate, through en bloc excision and re-implantation of the entire turbinate,Reference Weber, Werner and Hildenbrand21 or through medialisation of the turbinate and nasolacrimal duct during the procedure.Reference Suzuki, Nakamura, Nakayama, Inagaki, Murakami and Takemura22

Fig. 4. Endoscopic images of modified medial maxillectomy. (a) Boundaries of mucosal flap raised after sharp resection of inferior turbinate (IT), demonstrating inverted papilloma (IP). (b) Back-biting forceps used to resect bone inferior to head of inferior turbinate. (c) View of maxillary sinus with 70-degree endoscope, demonstrating anterior attachment of inverted papilloma and access to anterior and inferior maxillary sinus. (d) Anterior maxillary face following tumour resection. S = septum; MT = middle turbinate

To date, no studies have directly compared modified endoscopic medial maxillectomy with endoscopic maxillary mega-antrostomy in terms of surgical access, especially of the anterior maxillary face. The additional morbidity of the modified endoscopic medial maxillectomy compared with the endoscopic maxillary mega-antrostomy is minimal, however, and if the surgical pathology dictates a wider approach it should certainly be considered. In the context of recalcitrant inflammatory disease, both the modified endoscopic medial maxillectomy and endoscopic maxillary mega-antrostomy procedures have been reported to offer excellent disease control, with no requirement for further revision surgery on short- and long-term follow up.Reference Cho and Hwang10,Reference Costa, Psaltis, Nayak and Hwang14,Reference Wang, Gullung and Schlosser23,Reference Thulasidas and Vaidyanathan24

Pre-lacrimal recess approach

An approach to the maxillary sinus via the pre-lacrimal recess allows for direct access to the sinus with 0-degree endoscopes and instrumentation, and thus improved visualisation of its contents, whilst preserving the inferior turbinate and nasolacrimal duct (Figure 5).Reference Morrissey, Wormald and Psaltis25 This approach involves a vertical incision along the lateral nasal wall, just behind the piriform aperture, and medialisation of a mucosal flap with exposure of the bone of the antero-medial maxillary wall. Using sharp osteotomies or a drill, bone overlying the pre-lacrimal recess is removed and the lacrimal apparatus identified, thus allowing direct access into the maxillary sinus. After the operation, the mucosal flap is replaced and sutured with absorbable material. The pre-lacrimal recess approach is of value in the removal of recurrent antrochoanal polyps, benign tumours and refractory fungal infections,Reference Lin, Lin and Yeh26–Reference Yu, Guan, Zhang, Zhang, Jiang and Lian29 as well as being useful in approaches to the pterygopalatine and infratemporal fossae (Table 2).Reference Gao, Zhou, Dai and Huang30,Reference Zhou, Huang, Shen, Cui, Wang and Li31

Fig. 5. Endoscopic images of pre-lacrimal recess approach. (a) Sharp incision of mucosa (blue line) of head of inferior turbinate (IT). (b) Mucosal flap (MF) medialised with exposure of bone overlying pre-lacrimal fossa prepared for osteotomy. (c) View into maxillary sinus with well-exposed anterior maxillary face (Ant Max). (d) Head of inferior turbinate reconstituted and sutured in place with absorbable material.

The technique was initially described by Zhou et al. in 2013.Reference Zhou, Han, Cui, Huang and Wang32 These authors went on to describe the long-term results of this approach, including those of 71 patients with inverted papilloma.Reference Zhou, Huang, Sun, Li, Zhang and Cui33 The group reported complications such as upper lid and alar numbness, in 7 per cent of cases, and mild alar collapse, in 5.6 per cent of cases. A further series of 51 patients with sinonasal inverted papilloma was reported by Suzuki and colleagues.Reference Suzuki, Nakamura, Yokota, Ozaki and Murakami34 They reported no significant morbidity resulting from this technique, although partial osteotomy of the piriform aperture was required for access in eight cases, which can lead to alar collapse or notching at the alar margin.Reference Papesch and Papesch35 We would not advocate resection of the piriform aperture because of the above risks.

Two studies of computed tomograms demonstrated great variation in the anatomy of the pre-lacrimal recess. Kashlan and Craig found that the anteroposterior dimension of the pre-lacrimal recess was widest inferiorly, with a mean of 8.4 mm but a range of 1.9–14.2 mm, with the height having a range of 18.5–39.9 mm.Reference Kashlan and Craig36 Sieskiewicz et al. found that the width of the pre-lacrimal recess had a range of 0–15.2 mm at the level of the inferior turbinate, and in 30 per cent of patients studied the recess was too narrow to accept a 4 mm endoscope.Reference Sieskiewicz, Buczko, Janica, Lukasiewicz, Lebkowska and Piszczatowski37 However, even if the pre-lacrimal recess itself is narrow, the nasolacrimal apparatus can be mobilised and pushed medially in order to admit suitable instrumentation, without affecting its long-term function.

Trans-septal approach

The trans-septal approach was used to access the anterior maxillary face through asymmetrical septal incisions and an inferior cartilaginous septal resection. This approach was found to offer a 15–20 degree improvement in access in the axial plane.Reference Harvey, Sheehan, Debnath and Schlosser38,Reference Ramakrishnan, Suh, Chiu and Palmer39 However, an imaging study of six cadaveric heads suggested that, in some cases, access to the anterior-inferior part of the maxillary sinus might be limited by the height of the nasal floor.Reference Schreiber, Ferrari, Rampinelli, Doglietto, Belotti and Lancini40 This technique has fallen out of favour because of the excellent access that the pre-lacrimal recess approach offers, with no risk of the morbidities associated with the transseptal approach such as septal perforation; thus, we would not advocate its use unless access is limited through alternative approaches.

Endoscopic canine fossa trephine

Access may also be improved by performing canine fossa trephination, with the potential for better outcomes when treating severely diseased maxillary sinuses. A cadaveric study comparing canine fossa trephination with exclusively transnasal endoscopic access found that a greater amount of debris remained in the maxillary sinus following the transnasal approach (3.88 cm3 vs 2.88 cm3).Reference Feldt, McMains and Weitzel41 A single-blind, randomised study of 29 patients with unilateral chronic rhinosinusitis, by Byun and Lee, reported improved Sino-Nasal Outcome Test 20 (SNOT-20) outcome scores at 12 months in patients undergoing canine fossa trephination compared to those undergoing middle meatal antrostomy alone.Reference Byun and Lee42 A similar study by Seiberling and colleagues showed improved post-operative nasal endoscopy scores following canine fossa trephine compared with middle meatal antrostomy in 42 patients.Reference Seiberling, Church, Tewfik, Foreman, Chang and Ghostine43

There is an associated risk of damage to branches of the infraorbital nerve, namely the anterior superior alveolar nerve and the middle superior alveolar nerve, with the potential for adverse effects including facial paraesthesia and dental numbness. Traditional canine fossa approaches have been reported to result in adverse effects in 76 per cent of cases.Reference Singhal, Douglas, Robinson and Wormald44 A cadaveric study by Robinson and Wormald found that the anterior superior alveolar nerve emerged from its foramen as a double trunk in 25 per cent of the 40 sides dissected. One or more branches from the anterior superior alveolar nerve trunks were identified in 60 per cent, and a middle superior alveolar nerve was identified in 23 per cent. The authors concluded that the safest point to perform canine fossa puncture is on the mid-pupillary line, at the level of the floor of the pyriform aperture.Reference Robinson and Wormald45 A case series of 99 canine fossa approaches by Singhal et al. found that the use of anatomical landmarks reduced the frequency of adverse effects to 53 per cent, and the addition of endoscopic guidance reduced this further, to 40 per cent.Reference Singhal, Douglas, Robinson and Wormald44

The high initial adverse effects are very minor and largely soft tissue related, and are secondary to the excessive raising of soft tissue from the anterior maxillary face. Early studies reported a moderate rate of persistent paraesthesia of 28.6 per cent.Reference Robinson and Wormald45 However, with the use of anatomical landmarks with endoscopy, thereby allowing for refined trephination of the anterior maxillary face, the incidence of complications was reduced to 3.1 per cent (3 out of 97) at one month and 1 per cent (1 out of 97) at three months.Reference Seiberling, Ooi, MiinYip and Wormald46

Endoscopic Denker's approach

Tumours involving the pterygopalatine and infratemporal fossae may, in some cases, prove difficult to access via a transseptal approach or radical medial maxillectomy. An endoscopic Denker's (Sturmann–Canfield) approach can provide improved access.Reference Upadhyay, Dolci, Buohliqah, Fiore, Ditzel Filho and Prevedello47,Reference Prosser, Figueroa, Carrau, Ong and Solares48 This technique involves a soft tissue approach similar to the radical endoscopic medial maxillectomy, with a mucosal flap raised anterior to the inferior turbinate head and posteriorly along the floor of the nose, with exposure of the frontal process of the maxilla. Rather than staying medial to the piriform aperture, as in the endoscopic medial maxillectomy, the bony dissection is taken laterally over the face of the maxilla, whilst staying below the infraorbital nerve. The bony window therefore includes the medial wall, as in a radical endoscopic medial maxillectomy, but also the piriform aperture and anterior maxillary face.Reference Lee, Suh, Carrau, Chu and Chiu49

This approach may be appropriate in the management of extensive sinonasal tumours, but is associated with risks such as infraorbital nerve damage, alar collapse and nasolacrimal duct stenosis.Reference Lee, Suh, Carrau, Chu and Chiu49 Another potential application is in cases where tumours involve the nasolacrimal duct or ascending process of the maxilla, when the approach can be used as a means of obtaining an anterior margin. As the pre-lacrimal recess approach offers almost complete access to the entirety of the maxillary sinus, pterygopalatine and infratemporal fossae, we cannot recommend Denker's approach.

Conclusion

A variety of extended endoscopic approaches to the maxillary sinus, pterygopalatine and infratemporal fossae exist, each with its own anatomical limitations and potential complications. The pre-lacrimal recess approach offers excellent visualisation of the entire sinus in most cases of benign disease. The medial maxillectomy should be a technique held within the armament of the modern endoscopic rhinologist for when the surgical pathology necessitates wider access. Careful pre-operative review of the anatomy and disease burden is mandated prior to selecting an appropriate operative strategy.

Competing interests

None declared