Introduction

Malignancies of the temporal bone are very rare but aggressive tumours.Reference Morton, Stell and Derrick1 They are traditionally associated with a poor prognosis and a high rate of cancer recurrence.

Tumours of the temporal bone typically arise from the skin of the auricle or external auditory canal, or extend from the nearby parotid gland or peri-auricular skin. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common tumour type to occur in the temporal bone, although other histological subtypes of tumours of the skin, parotid, and bone or cartilage can invade the temporal bone.

The en bloc surgical approach for the excision of external auditory canal and temporal bone malignancies was initially described by Parsons and Lewis, in 1954.Reference Parsons and Lewis2 Radiotherapy was proposed as a treatment for these aggressive cancers by Lederman et al., in 1965.Reference Lederman, Jones and Mould3 Excisional biopsies can be performed when the tumour is small and limited to the soft tissue of the external auditory canal. For more invasive tumours, temporal bone resection is needed.

Lateral temporal bone resection involves resection of the bony external auditory canal, the tympanic membrane and the incus, with the medial limit defined at the level of the incudostapedial joint. The bony labyrinth and facial nerve are preserved. Temporal bone malignancies have a propensity to spread into the local lymphatics. The parotid and cervical nodes are at highest risk for involvement. Lateral bone resection is typically carried out with neck dissection and parotidectomy. Free-flap reconstruction is often required for large skull base or cutaneous defects following tumour ablation.

The current literature is limited because of the rarity of these tumours. This paper aimed to evaluate the survival outcomes over a 13-year period of patients who underwent lateral temporal bone resection in a tertiary referral centre as part of their treatment for metastatic skin cancer.

Materials and methods

A single-institute, retrospective chart review was carried out on all patients who underwent lateral temporal bone resection as part of their treatment for invasive tumours of the pinna, ear canal, parotid and temporal bone between January 2000 and December 2012.

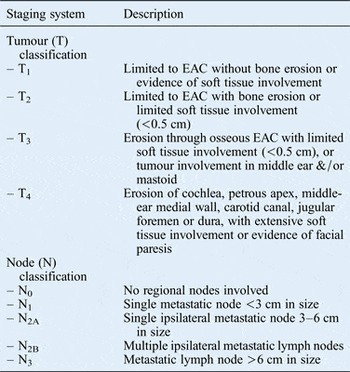

Patient demographics were obtained. Tumour variables were recorded, including the site of origin and the tumour–node–metastasis stage. Tumours were staged using the Pittsburgh staging system (Table I).Reference Arriaga, Curtin, Takahashi, Hirsch and Kamerer4 With regard to surgical variables, the undertaking of parotidectomy, neck dissection, facial nerve sacrifice and radiotherapy was assessed. Pathology variables included tumour histopathology, tumour size, and the presence or absence of both perineural invasion and lymph node involvement.

Table I Pittsburgh staging systemReference Arriaga, Curtin, Takahashi, Hirsch and Kamerer4

EAC = external auditory canal

The occurrence and timing of death or any recurrence were noted, and the date of last follow up was recorded. The overall survival and disease-free survival rates were calculated. Overall survival was defined as the time from the patients’ first appointment for the primary tumour until the date of last contact or death. Disease-free survival was defined as the time from the end of treatment for the original disease to the date of first recurrence.

Of note, neck dissection was indicated when nodal metastasis was suspected on pre-operative imaging or when the patient presented with an advanced tumour (an advanced T-stage lesion). Post-operative radiation was recommended in the following cases: for large skull base tumours, when more than one lymph node was positive, or in the presence of perineural, lymphovascular or intracranial invasion.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive variables were reported as means and categorical variables were reported as percentages. Life tables were used to describe the survival rates for a population. Curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier product limit method. The log-rank test was used to test the statistical significance of the differences between the actuarial curves. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were created from the data using PASW® Statistics software, version 18.

Results

Patient demographics

From 2000 to 2012, a total of 47 patients underwent temporal bone resection for primary (n = 21) or recurrent (n = 26) malignancies (Table II). Forty-five patients (95.7 per cent) were men and two (4.2 per cent) were women. Mean patient age was 75.5 years. The most common tumour site was the pinna (53.2 per cent).

Table II Patient characteristics

Surgery

Forty-one patients (87.2 per cent) underwent parotidectomy, with the facial nerve sacrificed in 11 cases (23.1 per cent) (Table III). Forty-four patients (93.6 per cent) underwent neck dissection; 24 patients (51.0 per cent) had pathologically positive lymph node involvement. Twenty-one patients (44.7 per cent) underwent surgery only as their primary treatment, and 25 patients (53.2 per cent) underwent surgery and post-operative radiotherapy.

Table III Surgical variables

There were three complications: one patient died as a result of disseminated intravascular coagulation due to an intra-operative haemorrhage, one patient suffered a cerebrovascular accident post-operatively and one patient developed sepsis post-operatively.

The most common reconstructive technique was a radial forearm free flap (23.4 per cent of cases), followed by a pectoralis flap (21.2 per cent) and a transpositional flap (12.7 per cent).

Radiotherapy

Post-operative radiotherapy was indicated in 25 patients. The treatment protocol involved intensity-modulated radiation therapy, with a dosage of 60–70 Gy delivered in 25–40 fractions over a period of 5–10 weeks.

Histopathology

The most common tumour type was SCC (85.2 per cent of cases), followed by basal cell carcinoma (10.6 per cent) and adenocystic carcinoma (4.2 per cent) (Table IV). Median overall tumour size was 4.6 cm (range, 1.2–9 cm). The presence of perineural invasion was recorded in 36.1 per cent of specimens. Fifty-one per cent of neck dissections were lymph node positive.

Table IV Histopathology

Disease staging

The majority of patients (95.4 per cent) had advanced disease (stage III or IV) (Table V).

Table V TNM Classification and disease stage

TNM = tumour–node–metastasis

Outcomes

Follow-up duration ranged from 18 months to 12 years, with an average follow up of 45 months. At the time of last follow up, 25 patients (53 per cent) had died. Nineteen patients had died of disease recurrence and six had died of other causes. Eighteen were alive with disease recurrence and four were alive without disease recurrence.

Of the 18 patients alive with recurrence, 6 had local recurrence, 3 had regional recurrence and 9 had distant recurrence. Histology indicated that 11 of the 18 post-operative specimens had positive deep margins.

The 5-year and 10-year overall survival rates for patients with temporal bone malignancies were 40 per cent and 23 per cent respectively (Figure 1). The five-year disease-free survival rate was 28 per cent (Figure 2).

Fig. 1 Overall survival Kaplan–Meier curve.

Fig. 2 Disease-free survival Kaplan–Meier curve.

With regard to disease-free survival, no statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were found between: primary and recurrent disease (p = 0.050; Figure 3), surgery and surgery with radiotherapy (p = 0.975; Figure 4), presence and absence of nodal disease (p = 0.288; Figure 5), presence and absence of perineural invasion (p = 0.240; Figure 6) and different tumour stages (p = 0.202; Figure 7).

Fig. 3 Disease-free survival Kaplan–Meier curves for primary versus recurrent disease.

Fig. 4 Disease-free survival Kaplan–Meier curves for surgery versus surgery and radiotherapy.

Fig. 5 Disease-free survival Kaplan–Meier curves for nodal disease (1) versus no nodal disease (0).

Fig. 6 Disease-free survival Kaplan–Meier curves for perineural invasion (1) versus no perineural invasion (0).

Fig. 7 Disease-free survival Kaplan–Meier curves for tumour staging (stages I–II vs stages III–IV).

Discussion

Tumours of the lateral temporal bone are extremely rare and aggressive. Because of the rarity of the tumours, there are few studies in the literature focusing on the outcomes for affected patients. There are currently only 10 studies, reporting more than 35 cases.Reference Moncrieff, Hamilton, Lamberty, Malata, Hardy and Macfarlane5–Reference Gidley, Roberts and Sturgis14

The largest study, by Gidley et al. (published in 2010), identified 124 patients with temporal bone SCC over a 60-year period, from 1945 to 2005.Reference Gidley, Roberts and Sturgis14 The five-year overall survival rate reported was 38 per cent and the disease-free survival rate was 60 per cent. In our study, the five-year overall survival rate was 40 per cent and the five-year disease-free survival rate was 28 per cent. The overall survival rate is relatively comparable to that reported by Gidley and colleagues, but there is a considerable difference between the disease-free survival rates.

The main difference between our study and the Gidley et al. study is in our higher rate of recurrences compared to their study. Over 55 per cent of our patients presented to us with recurrence at the site of previous excision, compared to only 20 per cent in the Gidley et al. study. As a national tertiary referral centre, patients are referred to our institute from other institutes. We were unable to establish if negative margins were obtained at the time of initial resection for these patients. A number of the patients who presented with late stage disease had not been followed up in the institute of their original treatment. These patients were also under the impression that they had curative treatment initially and delayed presentation. Patients with primary disease also had delayed presentation, which is evident in the lack of a statistically significant difference in survival between those with primary and recurrent disease.

Several factors may have contributed to our overall survival and disease-free survival rates. In Ireland, there is a propensity to a Celtic skin type, typically Fitzpatrick skin types I and II. Skin cancer is the most common cancer, with over 8000 new cases diagnosed per year in Ireland. Compliance with sun protection regimes is typically poor. The mean age of our patients was 75 years, which is higher compared to other studies, where mean patient age was 64 years. The older cohort of patients presenting to our unit tended to present late with more extensive disease.

In short, the patients with recurrence had similar survival rates to the patients with primary disease because of the extensive nature of their disease at initial presentation.

The Pittsburgh staging systemReference Arriaga, Curtin, Takahashi, Hirsch and Kamerer4 is a useful guide in management planning. In our institute, patients with stage I or II disease usually undergo lateral temporal bone resection, superficial parotidectomy and selective neck dissection (IIA, IIB and III). Those with stage III or IV disease typically undergo lateral temporal bone resection, with parotidectomy and neck dissection, and post-operative adjuvant radiotherapy.

• Lateral temporal bone tumours are extremely rare and aggressive

• There are few studies on outcomes for affected patients (10 studies reporting more than 35 cases)

• Aggressive surgical resection is warranted in treatment of these tumours

• In our series of 47 patients, 5-year overall survival and disease-free survival rates were 40 per cent and 28 per cent respectively

• Overall survival was comparable to other studies, but there was a difference in disease-free survival, probably because of recurrence at previous excision site (55 per cent of cases)

• Patients need to be treated effectively at initial presentation as treatment efficacy for recurrence is poor

Lateral temporal bone resection involves removing the tumour en bloc, without tumour spillage, and achieving negative margins. The tumour is excised en bloc to the mastoid cortex and a mastoidectomy is performed. In 61 per cent (11 of 18) of our patients who were alive with recurrence, post-operative specimens showed positive deep margins. All cases were discussed at our multidisciplinary team meeting. In these cases, the deep margins, although deemed positive, are not a true representation of the resection; unlike soft tissue margins, subsequent drilling of the mastoid bone after en bloc resection was undertaken to ensure macroscopic clearance of disease.