Introduction

Acute spontaneous epistaxis is a common ENT emergency. The latest available Health and Social Care Information Centre figures for England and Wales show that, in 2014–2015, 7935 completed consultant-managed episodes were categorised as ‘surgical arrest of bleeding from the internal nose’ and 9113 as ‘packing of cavity of nose’, with a mean length of hospital stay of 3 days in each category. The management of such patients consumes significant hospital resources.

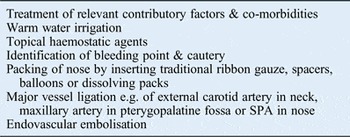

Bleeding post-trauma generally occurs from the territory of the ethmoidal arteries and is outside the scope of this review. Anterior spontaneous septal bleeds are usually successfully managed conservatively. There is no universal consensus as to the management of epistaxis, but a suggested hierarchy might involve the protocol outlined in Table I. Treatment of relevant contributory factors may require: adjusting anticoagulant use (unless co-morbidities mean that there is a greater risk of thrombosis), managing hypertension and investigating any potential blood dyscrasias. Haemostatic agents are less effective for posterior bleeds, as shown by a recent study of FloSeal®.Reference Khan, Reda El Badawey, Powell and Idris 1 Identification of the bleeding point and cautery is less applicable posteriorly, unless a skilled endoscopist is readily available. Packing of the nose if performed by the relatively inexperienced may prove inadequate. Pack insertion tends to require patient admission, especially when hypoxia is a significant concern. Endovascular occlusion can cause distal embolism.

Table I Traditional epistaxis emergency management protocol

SPA = sphenopalatine artery

Ideally, major vessel ligation is conducted as close to the source of bleeding as possible, to avoid collateral and cross-circulation. Thus, in the pre-endoscopic era, practice moved from ligation of the external carotid artery, in the neck, to accessing the maxillary artery via a Caldwell Luc approach. More distally still, the sphenopalatine artery has been ligated transnasally, with the opening of the posterior maxillary wall endoscopically, via a middle meatal antrostomy, thereby avoiding a sublabial incision.Reference White 2 Ligation was still lateral to the sphenopalatine foramen, but the author noted ‘the difficulty encountered isolating the artery on the medial side of the foramen’.Reference White 2

With the widespread adoption of endoscopic surgery for evaluation of the nose and sinus surgery, the currently preferred method for controlling persisting epistaxis is ligation of, or diathermy to, the sphenopalatine artery in the nose. This approach was advocated as long ago as 1963, when Malcomson wrote that ‘the sphenopalatine artery may be ligated as a secondary procedure, when primary ethmoidal occlusion fails to stop the bleeding; the sphenopalatine foramen and artery are exposed via the ethmoidal labyrinth.’Reference Malcomson 3 Further, as the rigid endoscope superseded the operating microscope, the first reports of a truly transnasal approach to the sphenopalatine artery appeared (in 1992).Reference Budrovich and Saetti 4

Using this approach, a paper from 1997 presented excellent results in 10 patients, who had surgery completed within an average operating time of 57 minutes per vessel.Reference Sharp, Rowe-Jones, Biring and Mackay 5 Similarly, in 2000, Wormald et al. reported sphenopalatine artery ligation in 13 patients, with control of bleeding in 92 per cent, without complications.Reference Wormald, Wee and van Hasselt 6 The authors concluded that the technique was ‘easy to perform, safe and effective’.Reference Wormald, Wee and van Hasselt 6

As endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation has become integrated widely into routine practice in the UK, there seems to be a trend towards increased and earlier recourse to it. A national survey of epistaxis management in 1993 collected data on 933 patients (from 102 consultants), and found that fewer than 1 per cent underwent formal arterial ligation (of maxillary, ethmoidal or external carotid arteries).Reference Kotecha, Fowler, Harkness, Walmsley, Brown and Topham 7 By 2012, Spielmann et al. reported that 7 per cent of their patients were undergoing arterial (sphenopalatine artery) ligation.Reference Spielmann, Barnes and White 8 The adoption of a formal treatment algorithm clearly increases uptake, as demonstrated in a completed audit cycle from Guy's Hospital, London.Reference Hall, Simons, Pilgrim, Theokli, Roberts and Hopkins 9 Of 50 patients admitted in 2009, 5 were considered suitable for endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation, but only 2 underwent the procedure. In 2010, the introduction of a treatment protocol showed, in a similar sample, that rates of surgery had increased to four of five eligible patients.Reference Hall, Simons, Pilgrim, Theokli, Roberts and Hopkins 9

Such practice is not universal. A recent multicentre audit shows wide variations in practice within the UK.Reference Hall, Blanchford, Chatrath and Hopkins 10 Only six units were studied, but the assessment of suitability for surgery varied from as high as 28 per cent in one unit to 12.5 per cent in another. Ultimately, only 9 per cent of the 166 patients admitted did actually undergo surgery or embolisation, and the authors questioned whether there is a need for a more centralised approach to epistaxis management, in fewer designated and specialist units.Reference Hall, Blanchford, Chatrath and Hopkins 10

Endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation has, surprisingly, seen less application in the prevention than in the control of nasal bleeding. A recent review of evidence-based management of epistaxis in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia showed no use of endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation.Reference Syed and Sunkaraneni 11

There is a call for earlier endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation in acute refractory epistaxis. Largely concentrating on the theoretical comparison of costs and length of stay, Dedhia et al. concluded that ‘ESPAL [endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation] should be offered as an initial treatment option for medically stable patients with posterior epistaxis’ in preference to posterior packing.Reference Dedhia, Desai, Smith, Lee, Schaitkin and Snyderman 12

A similar study of costing, but based on a personal case series, also suggested that ‘early timing of sphenopalatine artery ligation may reduce length of stay’.Reference McDermott, O'Cathain, Carey, O'Sullivan and Sheahan 13 Patients undergoing endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation within 24 hours of admission had a mean length of hospital stay of 3 days, compared with 6 days for those undergoing this surgery at a later date.Reference McDermott, O'Cathain, Carey, O'Sullivan and Sheahan 13

Senior surgeons may not have learned the technique in training, and even current trainees may deskill after subspecialisation. There are a lack of, and need for, data on endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation competency in the UK. In a very different practice environment, a Canadian survey of 100 trained surgeons, fellowship-trained rhinologists proved to be both younger (mean age of 38 years vs 50 years for otolaryngologists not subspecialty trained) and more confident in a variety of procedures, including endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation.Reference Walen, Rudmik, Lipkewitch, Dixon and Mechor 14 The authors concluded that ‘these procedures should be referred to fellowship-trained rhinologists who practice out of academic centres’.Reference Walen, Rudmik, Lipkewitch, Dixon and Mechor 14

Materials and methods

We searched Medline, Embase and Cochrane Library databases, from inception to 31st May 2016, using the following search term combinations: (1) ‘sphenopalatine artery’; (2) ‘sphenopalatine artery ligation diathermy’; (3) ‘epistaxis’; (4) 1 or 2, and ‘review’; (5) 1 or 2, and ‘systematic review’; (6) 1 or 2, and ‘meta-analysis’; (7) 1 or 2, and ‘controlled trial’; and (8) 1 and 3.

We sought high-quality prospective clinical studies, reviews or laboratory work relevant to the efficacy and safety of sphenopalatine artery ligation. Abstracts, identified from a review of article titles, were evaluated for inclusion by two authors (AE and LMF) working independently, with consensus if opinions differed. Papers were chosen if the abstracts suggested systematic reviews or meta-analyses, prospective controlled studies, or original basic science findings from laboratory studies. Audits and larger case series or cohort studies provided a lower level of evidence. Papers suggesting algorithms and consensus views for emergency treatment, together with case reports suggesting complications and the earliest reports of the procedure, were also included.

Abstracts were excluded if they suggested isolated case reports or small uncontrolled series that presented no new insight. No language restrictions were applied.

Results

The literature search suggested the following total numbers of relevant publications for each of the following terms: (1) ‘sphenopalatine artery’, n = 331; (2) ‘sphenopalatine artery ligation diathermy’, n = 99; (3) ‘epistaxis’, n = 1179; (4) 1 or 2, and ‘review’, n = 35; (5) 1 or 2, and ‘systematic review’, n = 26; (6) 1 or 2, and ‘meta-analysis’, n = 0; (7) 1 or 2, and ‘controlled trial’, n = 5; and (8) 1 and 3, n = 151.

From these, we selected and have made reference in the text to the following article types: systematic reviews, n = 3;Reference Spielmann, Barnes and White 8 , Reference Feusi, Holzmann and Steurer 15 , Reference Kumar, Shetty, Rockey and Nilssen 16 narrative reviews or algorithms, n = 8;Reference Syed and Sunkaraneni 11 , Reference Aval, Pabla and Flood 17 – Reference Daudia, Jaiswal and Jones 23 randomised controlled trials, n = 3;Reference Moshaver, Harris, Liu, Diamond and Seikaly 24 – Reference Cassano, Russo, Del Giudice and Gelardi 26 non-randomised controlled studies, n = 4;Reference Khan, Reda El Badawey, Powell and Idris 1 , Reference Cassano and Cassano 27 – Reference Holzmann, Kaufmann, Pedrini and Valavanis 29 case series or cohort studies, n = 9;Reference Umapathy, Quadri and Skinner 30 – Reference Eladl, Elmorsy and Khafagy 38 surveys and audits, n = 5;Reference Hall, Simons, Pilgrim, Theokli, Roberts and Hopkins 9 , Reference Hall, Blanchford, Chatrath and Hopkins 10 , Reference Walen, Rudmik, Lipkewitch, Dixon and Mechor 14 , Reference Srinivasan, Sherman and O'Sullivan 39 , Reference Yung, Sharma, Jablenska and Yung 40 cost-effectiveness studies, n = 5;Reference Dedhia, Desai, Smith, Lee, Schaitkin and Snyderman 12 , Reference McDermott, O'Cathain, Carey, O'Sullivan and Sheahan 13 , Reference Rudmik and Leung 41 – Reference Leung, Smith and Rudmik 43 anatomy studies, n = 6;Reference Shires, Boughter and Sebelik 44 – Reference Nalavenkata, Meller, Novakovic, Forer and Patel 49 case reports, n = 5;Reference Biswas, Ross, Sama and Thomas 50 – Reference Adam, Sama, Chossegros, Bedrune, Chesnier and Pradier 54 and historical articles, n = 6.Reference White 2 – Reference Kotecha, Fowler, Harkness, Walmsley, Brown and Topham 7

We concur with the comments of Spielmann et al. (2012).Reference Spielmann, Barnes and White 8 In a review of the literature published between 1956 and 2011, conducted to produce an ‘evidence-based review of epistaxis management’, their search criteria identified that ‘most presented expert opinion’ and we, too, had to pragmatically accept that ‘where relevant the highest level of evidence will be referred to’.Reference Spielmann, Barnes and White 8

Discussion

Logically, the occlusion of a vessel providing a major contribution to nasal blood supply should be of benefit in epistaxis control. Many case series attest to the efficacy of endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation, but there are theoretical objections that may question this presumption, as outlined below.

(1) Local variations in anatomy, especially of vessel branching, may mean incomplete occlusion, and long-term results might be compromised as new anastomoses develop. (2) The sphenopalatine artery is present bilaterally. Does cross-circulation require bilateral endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation in severe cases? (3) Other vessels, especially those derived from the internal carotid circulation, supply the nose. When should anterior ethmoidal artery ligation be included? (4) Are endoscopic diathermy and clipping equally effective? (5) Reports of effectiveness are based on the experience of expert rhinologists whose findings may not be reproduced by those lacking subspecialty skills. (6) It seems likely that early surgery carries added benefit, when compared to packing and examination under anaesthesia (EUA) with or without cautery, with which it is usually combined. However, the effect size is uncertain. Is it indispensable? (7) What is the current place of the procedure in practice? To whom and when should it be applied? (8) As with all endoscopic nasal surgery, the procedure carries some risk of damage to adjacent structures, especially if the operative field is obscured by blood. (9) Does endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation necessitate general anaesthesia, which carries attendant risks in patients with significant co-morbidities? (10) Is any investment in training and equipment outweighed by the economic benefits?

Despite these uncertainties, the technique has become standard practice. However, it lacks the evidence base for efficacy required by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence to approve it under ‘normal measures’ as a new invasive procedure.Reference Aval, Pabla and Flood 17

Feusi et al. suggested that ‘the most effective treatment for patients with posterior epistaxis, including costs, should be evaluated in a controlled clinical trial’.Reference Feusi, Holzmann and Steurer 15 Such a study is still lacking. Similarly, Kumar et al. commented that ‘the optimal surgical management for failed conservative measures in epistaxis remains unclear’, and recommended ‘that all units using this technique audit their results to see if the high success rates achieved in the literature are reproducible’.Reference Kumar, Shetty, Rockey and Nilssen 16

An evidence-based medicine review of epistaxis management published in 2012 also struggled with the low level of evidence for endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation, but decided that ‘early intervention with endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation for refractory epistaxis is safe, cost effective and has a high long-term success rate’.Reference Spielmann, Barnes and White 8 However, they also stated that the highest level evidence suggested that successful management should be “EUA ± SPA and/or AEA ligation” which reflects, at best, considerable uncertainty.Reference Spielmann, Barnes and White 8

Evidence base for efficacy

Preparing an audit of local practice of endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation, Rockey and Anand ‘looked to the literature for evidence of what was to be taken as a successful result and were surprised at the lack of published data on its efficacy or lack thereof’.Reference Rockey and Anand 18

There are very few comparative studies to address this gap in our knowledge; these largely comprise retrospective audits of outcomes, before and after the adoption of endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation. Three systematic reviews have demonstrated that most publications concern relatively small case series.Reference Spielmann, Barnes and White 8 , Reference Feusi, Holzmann and Steurer 15 , Reference Kumar, Shetty, Rockey and Nilssen 16

Srinivasan et al., in 2000, reported their experience of epistaxis management in the year prior to, and then subsequent to, the adoption of sphenopalatine artery diathermy (with or without anterior artery ligation or septoplasty) as a salvage procedure.Reference Srinivasan, Sherman and O'Sullivan 39 They showed that surgery provided immediate control in all but 1 out of 10 bleeds, with a length of hospital stay reduced from a mean of 3.9 to 2.1 days.Reference Srinivasan, Sherman and O'Sullivan 39

In that rarity, a randomised controlled trial, Moshaver et al. (2004) studied patients who continued to bleed after conventional packing, and who were then randomised to receive either repacking with Vaseline gauze or endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation.Reference Moshaver, Harris, Liu, Diamond and Seikaly 24 Subsequent analysis concentrated on cost reduction and length of stay; however, the authors reported 89 per cent efficacy in haemorrhage control, and length of stay was reduced from a mean of 4.7 days for the packed group to 1.6 days for the endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation group (p = 0.0001).Reference Moshaver, Harris, Liu, Diamond and Seikaly 24

Such a level of evidence attracted much citation, but reading beyond the abstract does suggest limitations to the trial. The study population of only 19 patients seems arbitrarily defined, with no power analysis suggested. In addition, although the authors report a 50 per cent failure rate in nasal packing, against 11 per cent for endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation, this difference failed to reach statistical significance (p = 0.141), possibly reflecting a type II error. No less than one-third of subjects were lost to follow up at three months. A subsequent review of the study describes it as a ‘cost-consequence analysis’, and is concerned by the lack of information on: methods of randomisation, methods of assessing patient satisfaction, reasons for withdrawal and whether analysis was conducted on an intention-to-treat basis. 19

A retrospective cohort study compared outcomes from endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation to those from all other surgical options employed for control of spontaneous epistaxis (including cautery and packing, submucous resection, and ligation of ethmoidal, maxillary and external carotid arteries). Endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation proved superior in terms of: immediate success rate, length of hospital stay, recurrence and patient satisfaction.Reference Umapathy, Quadri and Skinner 30 A similar review of 71 sphenopalatine artery occlusions suggested that use of diathermy rather than clipping significantly improved both short- and long-term outcomes.Reference Nouraei, Maani, Hajioff, Saleh and Mackay 31 No randomised controlled study has compared the two techniques.

Theoretical basis

The theoretical basis of endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation has been the presumption that the sphenopalatine is the sole terminal branch of the maxillary artery, although the anatomy of the arterial supply to the nose is variable and complex.

Successful ligation of the artery clearly assumes that it can be readily identified. Surgically, the crista ethmoidalis of the palatine bone lies almost immediately anterior to the foramen, and lifting a mucosal flap in the nose beyond this point should identify the main trunk. A middle meatal antrostomy may facilitate this.Reference Shires, Boughter and Sebelik 44 However, it is increasingly clear that the notion that the artery always enters the nose as a single entity, and subsequently divides into the posterior septal and posterior lateral nasal arteries is fallacious.

One study investigated the variations in the branching pattern of the sphenopalatine artery in 77 cadaver head sides.Reference Simmen, Raghavan, Briner, Manestar, Groscurth and Jones 45 The sphenopalatine artery and its branches were identified in 75 specimens, and, of these, 73 (97 per cent) had 2 or more branches medial to the crista ethmoidalis. Moreover, 49 (67 per cent) had 3 or more, 26 (35 per cent) had 4 or more and 1 specimen had 10 branches. In only two specimens was the artery present as a single trunk.Reference Simmen, Raghavan, Briner, Manestar, Groscurth and Jones 45 Another study investigating the foramen in relation to the crista in 66 skulls found the foramen to be single in 87 per cent, although more than 1 orifice was present in 13 per cent of cadavers.Reference Antunes Scanavini, Navarro, Megale, Lima and Anselmo-Lima 46 In another study of 20 specimens, the sphenopalatine artery was found to branch within the foramen in 80 per cent, before entering into the nose.Reference Midilli, Orhan, Saylam, Akyildiz, Gode and Karci 47 However, in 20 per cent of the specimens, the foramen was located superior to the horizontal lamella of the middle turbinate. An accessory foramen was present in 10 per cent, in an equal percentage of cases, with the posterior lateral nasal branch identified as two branches in a deep sulcus in the middle meatus.Reference Midilli, Orhan, Saylam, Akyildiz, Gode and Karci 47 Variation was also found in a study of the relationship of the sphenopalatine and posterior nasal arteries.Reference Schwartzbauer, Shete and Tami 48 The sphenopalatine artery exited as expected from the foramen in only 3 of 19 specimens (16 per cent), whereas it exited either much more posteriorly or from a distinct foramen directly posterior to the normal one in 8 specimens (42 per cent).Reference Schwartzbauer, Shete and Tami 48 A recent prospective analysis of 102 computed tomography scans of the paranasal sinuses suggested that the inferior turbinate concha and the posterior fontanelle are reliable landmarks for the sphenopalatine foramen.Reference Nalavenkata, Meller, Novakovic, Forer and Patel 49

The arterial supply does not therefore follow a uniform pattern. In addition, the supposition that interrupting it will diminish the blood supply to such an extent that it will halt bleeding is also unproven. There is some evidence that endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation does influence nasal blood supply, related to its adoption in the control of surgically induced haemorrhage. A retrospective study of nasal polyps patients compared bleed rates in those undergoing middle turbinate resection with those spared such resection, as part of polypectomy.Reference Cassano and Cassano 27 Endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation was necessary to control bleeding in 52.5 per cent of the study group, compared with 17.5 per cent of controls, and post-operative bleed rates were statistically significantly reduced in those who underwent ligation.Reference Cassano and Cassano 27

Enthusiasm for ligation has even led to a recommendation that it should replace packing in elective surgery. In 133 patients undergoing a wide range of nasal surgical procedures, including septoplasty, turbinoplasty and functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS), only 16 cases (12 per cent) were packed, while in the remaining 117 (88 per cent), the endoscopic control of bleeding (often just cauterisation) permitted the avoidance of packing.Reference Cassano, Longo, Fiocca-Matthews and Del Giudice 32 Of the latter group, in 29 patients (21.8 per cent), endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation was thought necessary. The authors concluded that ‘intra-operative control of bleeding allowed nasal packing to be avoided in a large percentage of cases’.Reference Cassano, Longo, Fiocca-Matthews and Del Giudice 32

Place in practice

Much effort has gone into identifying the role of surgery in the management of bleeding, with various algorithms.

The Wexham Park Criteria modelReference Lakhani, Syed, Qureishi and Bleach 33 suggests four requirements for surgery: (1) persistent posterior epistaxis uncontrolled by packing; (2) a haemoglobin drop of more than 4 g/dl and/or the requirement of a blood transfusion; (3) three episodes of recurrent epistaxis requiring repacking during a single admission; and (4) repeated hospital admission for recurrent ipsilateral epistaxis (more than three occasions in the last three months).

In a retrospective audit of their eight-year experience, the authors who developed those criteria found that every one of their patients who had undergone endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation fulfilled at least one criterion; unsurprisingly, persistent uncontrolled epistaxis proved to be the most common (21 out of 27 cases).Reference Lakhani, Syed, Qureishi and Bleach 33

The Dundee protocol is more interventionist; it suggests surgery, either when bleeding continues after the insertion of nasal packs or dressings, or where bleeding recurs after pack removal at 24 hours (48 hours in high-risk patients). In an algorithm of I–V steps, the final recommendation, for vascular intervention, is equivocal and indeterminate: ‘arrange EUA ± sphenopalatine artery and/or anterior ethmoid artery ligation’, and, for persisting bleeding, ‘consider further ligations (bilateral sphenopalatine artery, anterior ethmoid artery, external carotid)’ and ‘angiography ± embolisation’.Reference Spielmann, Barnes and White 8

Identification of the bleeding site is emphasised in the selection of vessel ligation. If this is not possible, a recent algorithm suggests ligating both the anterior ethmoid and the sphenopalatine arteries.Reference McClurg and Carrau 20 However, the authors concede that ‘despite the evidence provided by the current literature, a universal treatment protocol has not yet been established’.Reference McClurg and Carrau 20

The Guy's Hospital management algorithm addresses the practicalities of emergency management, often performed by relatively inexperienced junior doctors. Patients arriving in working hours should have any packs removed, with headlight nasal examination and possible cautery. Should the bleeding restart after pack removal, the recommendation is to repack anteriorly and leave the pack for 12–24 hours. Patients arriving out of hours should retain any packing until the morning round, but, if bleeding restarts or continues, packing is to be removed and replaced with post-nasal packs for 24 hours. In either case, if bleeding continues, the advice is to ‘consider posterior repacking by a senior doctor’. Sphenopalatine artery ligation was only undertaken following failure at this stage, or if packs were required for longer than 48 hours.Reference Hall, Simons, Pilgrim, Theokli, Roberts and Hopkins 9

In 2005, Loughran et al. could write ‘arterial ligation of whatever form is not the first line management of epistaxis. The vast majority of both anterior and posterior epistaxis can be managed by direct means’.Reference Loughran, Hilmi and McGarry 21 However, consideration of the morbidity and limited effectiveness of posterior nasal packing, with theoretical modelling of cost effectiveness, has actually led some to recommend that endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation is resorted to much earlier, and in preference to posterior packing, with the former being considered as ‘an initial treatment option for medically stable patients with posterior epistaxis’.Reference Dedhia, Desai, Smith, Lee, Schaitkin and Snyderman 12

Long-term outcomes

Few papers have addressed the long-term benefit of endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation. In a Scottish multicentre audit, outcome measures were defined in terms of epistaxis recurrence in the immediate post-operative period and at ‘long-term follow up’ (which in practice was a minimum of nine months).Reference Abdelkader, Leong and White 34 It showed that all recurrences requiring intervention (2 out of 43; 5 per cent) occurred within one month of surgery.Reference Abdelkader, Leong and White 34

A Danish multicentre study following up results after a mean of 6.7 years found that 78 per cent of sufferers had experienced no further bleeds, but 10 per cent had required early revision surgery.Reference Gede, Aanaes, Collatz, Larsen and von Buchwald 35 A similar UK study suggested that, at the five-year review, 89.4 per cent who underwent endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation had experienced no further bleeds.Reference George, Smatanova, Joshi, Jervis and Oluwole 36

Contralateral sphenopalatine artery and other vessels

Whether to address both sphenopalatine arteries and the anterior ethmoidal arteries remains uncertain. In profuse haemorrhage, the site of bleeding may be initially uncertain. In a long-term review of outcomes, George et al. reported that, of 15 patients who had been initially packed bilaterally, only 1 needed bilateral endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation.Reference George, Smatanova, Joshi, Jervis and Oluwole 36

In a case series of 41 patients, the re-bleeding rate was not affected by simultaneous septoplasty or anterior ethmoidal artery ligation.Reference McDermott, O'Cathain, Carey, O'Sullivan and Sheahan 13 In a study of 33 endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation procedures over 5 years, 3 of 4 bleeds not controlled were successfully managed by subsequent anterior ethmoidal artery ligation.Reference Howe, Wazir and Skinner 37 The authors concluded that failure of endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation may reflect an incorrect choice of target vessel.Reference Howe, Wazir and Skinner 37 In a retrospective comparative study, which compared endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation in isolation with endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation and concomitant anterior ethmoidal artery ligation, the authors reported persisting bleeding in 3 out of 20 patients in the former group and 0 out of 25 in the latter.Reference Asanau, Timoshenko, Vercherin, Martin and Prades 28 This difference did not, however, achieve statistical significance, possibly reflecting the small study size.Reference Asanau, Timoshenko, Vercherin, Martin and Prades 28

Holzmann et al. (2003) demonstrated the value of occlusion of the septal branch of the sphenopalatine artery, as part of endoscopic ligation.Reference Holzmann, Kaufmann, Pedrini and Valavanis 29 They prospectively compared outcomes for 95 patients in 3 treatment groups: one group underwent endoscopic diathermy of an identified bleeding point, another underwent the occlusion of vessels at the sphenopalatine artery foramen, and the third group underwent modified endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation, identifying the conchal and septal branches. Re-bleeding rates for the three groups were 21 per cent, 16.7 per cent and 4.3 per cent, respectively.Reference Holzmann, Kaufmann, Pedrini and Valavanis 29 More recently, the septal artery has again been targeted as a modification of endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation, in an attempt to achieve occlusion proximal to the bleeding source.Reference Cooper and Ramakrishnan 22

A truly unique failure of endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation was reported in this journal, which is understandable when imaging confirmed a lack of significant blood supply from the bilateral sphenopalatine arteries, with the main feeding vessels being the anterior ethmoid arteries.Reference Biswas, Ross, Sama and Thomas 50

Need for general anaesthesia

Isolated reports suggest that endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation can be performed under local anaesthesia when co-morbidities contraindicate general anaesthesia. Using a greater palatine nerve block with topical anaesthesia, Jonas et al. performed two successful endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligations; indeed, in one case it was combined with anterior ethmoidal artery ligation.Reference Jonas, Viani and Walsh 51

A recent and much larger study showed that this could become standard practice, and was remarkably acceptable to the patient. In a 2-cycle audit, Yung et al. reported detailed findings on 21 patients undergoing endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation under local anaesthesia, which has been their standard practice for some years.Reference Yung, Sharma, Jablenska and Yung 40 Following their first 10 procedures (2010–2012), they noted that the commonest complaints, from their awake patients, were of blood trickling down the throat during the operation and of a burning sensation associated with bipolar diathermy usage. For the subsequent 12 procedures (2012–2014), they slightly modified their practice (with local infiltration and temporary occlusion of the posterior choana) and noted a statistically significant benefit in patient satisfaction scores. Only one bleed required conversion to a general anaesthetic and that was purely to allow anterior ethmoid artery ligation for continuing blood loss.Reference Yung, Sharma, Jablenska and Yung 40

Complications

A small number of case reports and case series suggest minor changes in nasal physiology and very rarely major complications. The autonomic innervation of the nose enters with the posterior nasal nerve, which, after crossing the sphenopalatine foramen, distributes to the mucosa, following the branches of the sphenopalatine vessels.

Eladl et al. (2011), using bipolar diathermy, cauterised the sphenopalatine neurovascular bundle without any attempt at nerve dissection.Reference Eladl, Elmorsy and Khafagy 38 Mild eye dryness occurred in 9.5 per cent of cases. Subjective nasal dryness occurred in 81 per cent, but was significant in only 9.5 per cent. A small minority of cases showed altered dental and nasal mucosal sensations.Reference Eladl, Elmorsy and Khafagy 38

There is indeed high-level evidence that endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation affects the autonomic supply to the nasal mucosa, something desirable and intentional in rhinitis management where a drying effect is desired. In a prospective double-blinded study, 60 patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps were randomised to receive FESS, with or without endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation.Reference Cassano, Marioni, Russo and Cassano 25 The authors examined symptom scores, endoscopy appearance and rhinomanometry prior to surgery, and at one and three years after surgery. Both groups showed a statistically significant improvement in airway, but only the endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation group showed a benefit for rhinorrhoea (p < 0.001) and sneezing or itching (p < 0.01).Reference Cassano, Marioni, Russo and Cassano 25

These authors, in different patients, again produced high-level evidence that dividing the sphenopalatine artery pedicle does something to nasal parasympathetic innervation that, although beneficial in rhinitis, might over-dry a healthy nasal airway.Reference Cassano, Russo, Del Giudice and Gelardi 26 In 30 patients with turbinate hypertrophy due to vasomotor rhinitis, the authors randomised subjects to receive turbinoplasty with and without endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation. Outcome measures again included changes in endoscopic appearance and rhinomanometry, but additionally included a study of mucociliary transit time and nasal cytology at one year. Both treatments improved nasal resistance and mucociliary transit times, but with a significantly greater benefit (p < 0.05) for the latter in the endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation group. A highly significant change, beneficial for a hypersecreting nose, was noted in nasal cytology studies following ligation.Reference Cassano, Russo, Del Giudice and Gelardi 26

Any vessel ligation carries a theoretical risk of ischaemic necrosis, although the customary rich vascularity of the nasal airway makes this unlikely. Nevertheless, a 45-year-old man, who underwent bilateral sphenopalatine artery ligation to control intractable posterior epistaxis, re-presented after 4 months with nasal obstruction and crusting.Reference Elsheikh and El-Anwar 52 A posterior septal perforation and bilateral necrosis of the lower parts of the middle turbinates required debridement.Reference Elsheikh and El-Anwar 52 Ischaemic necrosis of the inferior turbinate had been reported as a very rare complication, a decade earlier.Reference Moorthy, Anand, Prior and Scott 53 The risk might be increased in patients known to have peripheral vascular disease, as illustrated by a case report of what was a bilateral embolisation, not ligation, of the sphenopalatine arteries that resulted in palate necrosis.Reference Adam, Sama, Chossegros, Bedrune, Chesnier and Pradier 54

Economics

An early study compared charges and costs for endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation and angiography with embolisation for posterior epistaxis in 25 patients.Reference Rudmik and Leung 41 The authors concluded: ‘with equal efficacy, at least equal costs and equal risk, and additional diagnostic advantages, endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation is a more rational treatment for posterior epistaxis’.Reference Rudmik and Leung 41

In a theoretical exercise (a standard decision analysis model), endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation showed a cost saving when compared to posterior packing, when employed as first-line therapy.Reference Miller, Stevens and Orlandi 42

The issue remains unresolved. A subsequent study investigated patient risk and cost effectiveness, but again relied on a literature-derived risk analysis, based on the management of a 50-year-old man with no other co-morbidities, which does seem unrepresentative of the typical epistaxis patient.Reference Leung, Smith and Rudmik 43 Six strategies were compared, involving various sequences of posterior packing, endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation and embolisation. Unsurprisingly, the last carried the highest risk. The conclusion, of what again is a theoretical exercise, was that, on both patient risk and cost-effectiveness grounds, the authors would recommend endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation as first-line management, with posterior packing or embolisation in reserve. The algorithm derived does seem disappointingly inconclusive.Reference Leung, Smith and Rudmik 43

Most recently, a case note review of 45 patients undergoing endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation showed that those undergoing the surgery within 24 hours of admission showed much lower treatment costs than those for whom it was delayed (€5905 vs €10 001), as length of stay was significantly reduced (3 vs 6 days) by earlier intervention.Reference McDermott, O'Cathain, Carey, O'Sullivan and Sheahan 13

Conclusion

Despite many efforts to derive consensus guidelines and an algorithm for the management of refractory epistaxis, there still seems to be variation in national practice. Often such cases are managed with repeated packing. The limited evidence confirms the conclusions derived by Daudia et al. back in 2008: ‘in patients with refractory epistaxis, the role of endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation is well established, but many departments lack guidelines’.Reference Daudia, Jaiswal and Jones 23

The effect size remains an issue, but endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation seems an indispensable tool, and it must be questioned whether units or individuals unable to offer it consistently can safely manage acute epistaxis. Future research might address when to tackle the contralateral sphenopalatine artery or other vessels, the choice of ligation or diathermy, and the place of endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation in any algorithm for epistaxis management.