Introduction

Tears are secreted by the lacrimal and accessory lacrimal glands in the eye. They pass through the lacrimal puncta into the upper and lower canaliculi and through the common canaliculus into the lacrimal sac. From the lacrimal sac, tears flow into the inferior meatus of the nasal cavity through the nasolacrimal duct. The production and drainage of tears are normally in equilibrium.

The aetiology of epiphora can be congenital (due to developmental defect) or acquired. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction occurs in approximately 6 per cent of newborn infants.Reference Paul1

Since its description in 1904 by Toti,Reference Toti2 with modifications by Dupuy-Dutemps and Burguet in 1921,Reference Dupuy-detemps and Bourguet3 external dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) has been regarded as the gold standard procedure for the management of epiphora secondary to nasolacrimal duct obstruction. A high success rate of external DCR (90–99 per cent) has been reported in the literature.Reference McPherson and Egleston4–Reference Rosen, Sharir, Moverman and Rosner7 Despite this, over the last 20 years there has been a transition from external DCR to endonasal DCR. The endonasal technique, although first described by Caldwell in 1893, has only gained popularity in the past decade following the development of endoscopic nasal surgery. The principal advantage of the endonasal technique is that it is performed endoscopically through the nose and does not require an external skin incision. Recent studiesReference Wormald and Tsirbas8, Reference Wormald9 with endonasal DCR have shown success rates comparable with external DCR approaches.

Dacryocystorhinostomy involves creating a drainage port from the lacrimal sac into the nasal cavity by removing part of the bone of the lacrimal fossa. The lacrimal fossa is formed by the thicker frontal process of the maxilla anteriorly and the thinner lacrimal bone posteriorly. The superior portion of the tunicate process is a landmark for the lacrimal bone, which lies immediately anterior to it. The nasolacrimal sac is 10 mm in length and is located anterior to the middle turbinate. The axilla of the middle turbinate marks the superior point of the lacrimal sac in the majority of patients.Reference Metson10, Reference Sperkelson and Barberan11 The nasolacrimal duct, a continuation of the lacrimal sac, passes laterally and posteriorly through the maxilla for 12 mm and terminates in the inferior meatus at the junction of the anterior one-third and the posterior two-thirds.

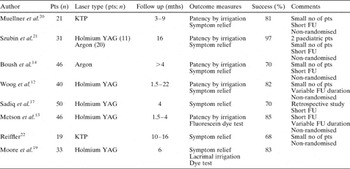

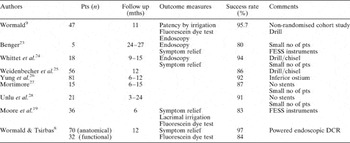

The reported success rates for endonasal DCR are variable, ranging between 63 and 97 per cent.Reference Woog, Metson and Puliafito12–Reference Nussbaumer, Schreiber and Yung16 Sadiq et al. Reference Sadiq, Hugkulstone, Jones and Downes17 performed endonasal laser DCR and reported a short term success rate of 78 per cent at three months, which reduced to 59 per cent at 12 months. The success rate of endonasal surgical DCR in adults has been reported as 88.2 per cent by Cokkeser et al. in 2000,Reference Cokkeser, Evereklioglu and Er18 83 per cent by Moore et al. in 2002Reference Moore, Bentley and Olver19 and 97 per cent by Wormald et al. in 2004.Reference Wormald and Tsirbas8 However, a search of the literature revealed only level II to III evidence when comparing the efficacy of laser and non-laser techniques. The current literature consists mainly of retrospective case reviews and prospective, non-randomised, controlled studies (Tables I and II). Hence, as level I evidence was lacking, the objective of this study was to undertake a prospective, randomised, controlled trial in order to compare the subjective outcomes of endonasal surgical and endonasal laser DCR techniques.

Table I Endonasal laser DCR: studies

DCR = dacryocystorhinostomy; pts = patients; mths = months; KTP = potassium titanyl phosphate; no = number; FU = follow up; YAG = yttrium aluminium garnet; n = number.

Table II Endonasal surgical DCR: studies

DCR = dacryocystorhinostomy; pts = patients; mths = months; no = number; FESS = functional endoscopic sinus surgery

Materials and methods

Ethical approval was granted by the Gloucestershire local research ethical committee (study number 00/166G) prior to commencing the study.

Following a pilot study, a sample size calculation indicated that 120 patients were required to undergo complete follow up in order to detect, with 80 per cent power and 5 per cent significance level, a difference in perceived success of surgery of 20 per cent. Thus, a total of 126 patients requiring surgery to relieve primary, acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction was prospectively recruited into the study between September 2001 and November 2003.

Exclusion criteria included an age of less than 21 years and lack of consent.

All patients were given information sheets and a verbal explanation of the study prior to consent being requested. All patients gave written informed consent to treatment.

Patients were randomised to receive endonasal laser DCR or endonasal dissection DCR, using envelopes provided by the Gloucestershire Research and Development Support Unit. All the patients had been evaluated and listed for surgery by the ophthalmology team.

Pre-operative assessment included: (1) establishing a symptom score for epiphora (patients were asked to score their symptoms on a scale of zero to 10, zero being no tearing at all and 10 being tearing all the time; (2) evaluating fitness for anaesthetic; and (3) taking a detailed history (including previous surgery, age, sex and general medical condition).

Surgery was conducted by experienced members of the ophthalmology and otorhinolaryngology teams.

The patients were given a choice between general anaesthesia (GA) and local anaesthesia (LA). Local anaesthesia was achieved by placing a nasal pack soaked in Moffat's solution (2 per cent cocaine, 20 per cent of 1:1000 adrenaline and sodium bicarbonate) in the middle meatus and nasal cavity to initiate mucosal decongestion. One per cent lidocaine with 1:80 000 adrenaline was infiltrated with a dental syringe submucosally into the middle turbinate and over the maxillary line of the lateral wall of the nose. Peri-orbital local anaesthesia was achieved with amethocaine eye drops and subsequent infiltration of 1 per cent lidocaine around the lacrimal canaliculi and lacrimal sac and through the facial tissues down to the frontal process of the maxilla. If the patient opted for GA, the nasal cavity was prepared in the same way.

The lacrimal canaliculi were dilated using a lacrimal probe. A vitrectomy light probe was then passed through either the superior or the inferior canaliculus into the lacrimal sac. The light probe transilluminated the lateral nasal wall, aiding surgical localisation of the lacrimal sac.

Endonasal examination was conducted with a video camera attached to a 0°, 4 mm diameter, rigid Hopkin's rod endoscope. Endonasal surgical dissection was conducted by elevating a flap of mucosa, identifying the suture line between the frontal process of the maxilla and the lacrimal bone, and removing the bone overlying the lacrimal sac with a Kerisson sphenoid bone punch. The bone removed included portions of the uncinate process and lacrimal and maxillary bones, leading to exposure of the medial wall of the lacrimal sac. The sac was then opened with a keratome knife. An inferiorly based mucosal flap was used to cover the exposed bone.

The endonasal laser technique was conducted using a potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser, after suitable protection of the patient and staff. The laser settings were: 5.0 W, 0.5 seconds' duration and 0.5 second interval. The laser was used to resect the mucosa and bone and to incise the lacrimal sac. When the light probe was visible, the opening into the lacrimal sac was enlarged to between 5 and 10 mm (using laser alone in the endonasal laser technique). Bicanalicular Silastic® stents were then passed through the upper and lower canaliculi into the nasal cavity and secured with multiple knots to form a continuous loop. This tubing served to stent the surgical ostium, and was removed three months post-operatively in the ENT out-patient department.

Intra-operative assessment included: (1) surgical duration; (2) ease of procedure (on a 10-point scale, with a lower score representing easier procedure); and (3) complication or difficulty experienced during the procedure.

Post-operative assessment included establishing symptom scores (on a scale of zero to 10) at three and 12 months, either during an out-patient appointment or by telephone survey. The patients were asked, at three and 12 months, if they considered the operation to be a success or a failure. The duration of hospital stay was also recorded.

Patients' symptoms were considered to be improved, at three and at 12 months, if their scores were reduced by at least two points on the zero to 10 scale, compared with pre-operative scores. The proportion of patients with improved symptom scores, and the proportion rating the procedure as successful, were compared between the randomised treatment groups, using the chi-square test. A test of odds ratio homogeneity was used to assess whether any differences in symptom improvement between the randomised groups had been influenced by: LA vs GA; differing age (under vs over 70 years); and laterality (right- vs left-sided DCR). The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Analysis

One hundred and twenty-six patients were recruited to the trial, 42 men and 84 women. The age range was 28–91 years (median 74 years) in the laser cohort and 25–89 years (median 69 years) in the surgical cohort. Fifty-two per cent of the endonasal laser DCRs and 50 per cent of the endonasal surgical DCRs were performed under GA. Eight patients randomised to receive laser DCR actually underwent a procedure combining endonasal laser and surgical techniques, because of technical difficulties mainly related to thicker bone. These patients were analysed by ‘intention to treat’, within the laser group to which they had originally been allocated. Forty-nine procedures were performed on the left and 77 on the right side (Table III). None of the patients underwent simultaneous, bilateral DCR. The median ages for GA and LA were 69 and 75 years, respectively. All patients underwent pre-operative syringing prior to listing for surgery.

Table III Randomised groups

EL = endonasal laser; DCR = dacryocystorhinostomy; ES = endonasal surgical; yr = years

Intra-operative complications included both anatomical and pathological obstacles. These included: prominent agger nasi cells impeding access (two patients); concha bullosa or large middle turbinate requiring excision (five); adhesions from previous surgery (two); intra-operative bleeding; deviated nasal septum requiring septoplasty (three); and nasal polyps (two). One patient was noted intra-operatively to have granulation tissue in the nasal mucosa; however, both biopsy and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were negative. One procedure was abandoned due to inability to probe the canaliculi.

Immediate post-operative complications included: post-operative bleeding requiring overnight stay (one patient); minor vestibular abrasions (two); and periorbital ecchymosis following infiltration with local anaesthetic (five). One patient developed a post-operative pyocoele as a late complication, and eventually underwent an external DCR. One patient listed for LA actually underwent their procedure under GA due to anxiety. Three patients randomised to laser treatment were converted to surgical treatment due to technical difficulties. Five patients randomised to laser treatment actually underwent a combined laser and dissection technique (Table III).

For the total cohort, the ease of the procedure (on a scale of zero to 10) ranged from a minimum of one to a maximum of 10, and had a mean value of 4.5 in the laser group and 4.1 in the surgical group. Eight patients randomised to receive endonasal laser DCR had to be converted to laser-assisted surgical DCR due to technical difficulties; however, they were analysed within their originally allocated group. The average duration of the procedure ranged from a minimum of 10 minutes to a maximum of 60 minutes, with means of 25 and 20 minutes in the laser and surgical groups, respectively. The laser DCR procedure took an average of 5 minutes longer compared with the surgical DCR procedure. The laser setting-up time was not included in the operating time.

In the laser DCR group, symptomatic success was reported by 81.7 per cent (49 patients) at three months and by 68.3 per cent (41 patients) at 12 months. In the surgical DCR group, symptomatic success was reported by 75.8 per cent (50 patients) at three months and by 74.3 per cent (49 patients) at 12 months (Table IV).

Table IV Treatment success rates

Pts = patients; mths = months

Patients' assessments of treatment outcome was queried at three and 12 months; the results are shown in Tables V to VIII.

Table V Patients' assessment of success at 3 months

DCR = dacryocystorhinostomy

Table VI Patients' assessment of success at 3 months: chi-square testing

* 2-sided. df = degrees of freedom; sig = significance; assoc = association

Table VII Patients' assessment of success at 12 months

DCR = dacryocystorhinostomy

Table VIII Patients' assessment of success at 12 months: chi-square testing

* 2-sided. df = degrees of freedom; sig = significance; assoc = association

Improvement in patients' symptom scores was not found to be significantly influenced by choice of LA vs GA, laterality or age (i.e. under vs over 70 years).

Discussion

Reported success rates for endonasal dacryocystorhinostany have ranged between 63 and 97 per cent, as is evident from Tables I and II.Reference Woog, Metson and Puliafito12–Reference Mathew, McGuiness, Webb, Murray and Esakowitz15 Unfortunately, disparity regarding study design, operative techniques and outcome measures precludes any meaningful comparison of the studies in question.

Key questions arise about the effectiveness of endonasal surgical DCR compared with endonasal laser DCR. These concern success rate, operative time, cost-effectiveness and ease of procedure. There is anecdotal evidence that the endonasal laser DCR success rates are lower compared with endonasal surgical DCR. The reasons postulated in the past include the smaller rhinostomy and more fibroblastic activity (resulting in excessive scarring and stenosis of the rhinostomy) associated with the laser technique, compared with non-laser dissection. Although randomised, controlled trials comparing external and endonasal DCR techniques have been attempted,Reference Hartikainen, Grenman, Puukka and Seppa29 there are no published, prospective randomised controlled trials comparing endonasal laser DCR with endonasal surgical DCR. Moore et al. Reference Nussbaumer, Schreiber and Yung16 carried out a prospective, non-randomised trial to determine subjective and objective outcomes after endonasal surgical DCR and endonasal laser DCR. The six-month symptomatic success rates were 83 per cent after endonasal surgical DCR and 71 per cent after endonasal laser DCR; this difference was not statistically significant. In our study, the 12-month symptomatic success rate was 74.3 per cent in the endonasal surgical DCR group and 68.3 per cent in the endonasal laser DCR group – i.e. higher in the surgical group, although this difference was not statistically significant. Findings in the endonasal laser DCR group suggested that there was a deterioration of results over time, although this change was not statistically significant. Longer term follow up is needed to ascertain whether there is a significant change in results over time. At three months, endonasal laser DCR had better results than endonasal surgical DCR. At 12 months, however, endonasal surgical DCR had better results than endonasal laser DCR.

As has been noted, eight of the patients randomised to the endonasal laser dacryocystorhinostancy group actually required additional ‘cold steel’ surgical instrumentation in order to remove hard bone covering the lacrimal sac. As these patients had been randomised to the endonasal laser DCR group, their analysis was conducted by intention to treat within the laser group. In addition, mucosal and lacrimal sac incisions were made with the KTP laser. One could argue, however, that because these eight patients had received additional instrumentation, they had actually undergone endonasal surgical DCR. This would have the effect of decreasing the apparent success rate of endonasal laser DCR.

As with any new procedure, various techniques of endonasal dissection DCR have been developed. Published endonasal surgical DCR techniques have used various instruments, such as drills, Hayek's punch forceps, osteotomes and curettes, in order to create the rhinostomy. Likewise, endonasal laser DCR with different types of laser (i.e. holmium yttrium aluminium garnet, and KTP) has been described. The endonasal removal of bone has been performed by various non-laser and laser techniques. Non-laser endosurgical DCR techniques have included use of the otologic cutting drill, debrider and neurosurgical microrongeurs. The laser techniques can be further classified into endolaser DCR (i.e. treatment entirely by laser) and endolaser-assisted surgical DCR (i.e. treatment using laser and surgical instruments). One of the advantages of the endonasal technique is that it can be undertaken using LA. This therefore increases the number of patients who may be considered for such surgery, to include, in particular, the elderly and those wishing to avoid a facial scar. Other advantages include: the absence of an external incision, which may be prone to infection; reduced surgical time with less morbidity; the possibility of bilateral surgery; preservation of the canthal anatomy; reduced bleeding; simultaneous management of concomitant sino-nasal pathology; reduced tissue injury; reduced post-operative recovery time; and reduced length of hospital stay.

Comparison of the various endonasal studies is hampered by lack of standardisation of outcome measurement and of when (during post-operative follow up) results should be assessed. A criticism of our study could be that we did not undertake any objective measure of post-operative success or failure. The argument against using an objective measure is that even such objective evaluations as lacrimal irrigation, endoscopic visualisation of rhinostomy and functional endoscopic dye tests give false negative and false positive results, and that therefore anatomical success does not always correlate with symptomatic success.

The inherent factors of increased cost and operative time must be considered when an expensive piece of equipment such as a surgical laser is introduced into the operating theatre. The costs involved were higher with laser surgery (considering the initial cost of equipment and the additional costs of disposable equipment, staff training and maintenance; a detailed cost calculation is beyond the scope of this study). In our study, the endonasal surgical DCR group had an additional advantage over the endonasal laser DCR group as regards speed and ease of procedure.

Several reports have compared external and endonasal DCR.Reference Bartley30, Reference Hartikainen, Antila, Varpula, Puukka, Seppa and Grenman31 Most show that external DCR has a higher primary success rate. The advantages of endoscopic DCR include lack of cutaneous incision, avoidance of disruption of the medial canthus, and simultaneous correction of nasal pathology and lacrimal pump function. The disadvantages include limited visualisation of the nasolacrimal sac and duct, which is needed to inspect such pathology as dacryoliths.

Reduced operative time and length of hospital stay are distinct advantages of endonasal DCR as compared with external DCR. Sadiq et al. Reference Sadiq, Hugkulstone, Jones and Downes17 carried out a non-prospective, randomised, comparative study comparing the results of conventional external DCR vs endonasal laser DCR using holmium yttrium aluminium garnet laser. Overall, the functional success rates were comparable. Of note was the significantly lower average operative time of 21 minutes (p < 0.00001) and the much higher frequency of LA and day case surgery (94 per cent) in the endonasal laser DCR group. In the conventional external DCR group, the average operating time was 67.4 minutes and the mean post-operative stay was 2.3 days. In our study, all but one patient underwent treatment as day cases, and the average operating time was 22.5 minutes. In a prospective randomised controlled trial carried out by Hartikainen et al.,Reference Hartikainen, Antila, Varpula, Puukka, Seppa and Grenman31 the average surgical duration for endonasal laser DCR (23 minutes) was three times shorter than that for external DCR (78 minutes) (p < 0.0001).

• This prospective, randomised, controlled study compared the outcomes of endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) conducted by laser and surgical techniques in 126 patients

• In the laser group, symptomatic success rates were 82 per cent at three months and 68 per cent at 12 months. In the surgical group, symptomatic success rates were 76 per cent at three months and 74 per cent at 12 months There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups

• In the endonasal laser DCR group, a trend towards falling success rate with time may reflect post-laser fibrosis and scarring

• Choice of local or general anaesthetic did not influence symptomatic success rate

Historically, all DCRs were performed under GA, therefore excluding medically unfit patients. The majority of patients with epiphora are elderly. Patients with poor health often pose a greater anaesthetic and surgical risk. Dresner et al. Reference Dresner, Klussman, Meyer and Linberg32 reported 76 DCRs performed under LA on an out-patient basis, with a success rate of 94 per cent. Tripathi et al. Reference Tripathi, Lesser, O'Donnell and White33 reported endonasal laser DCR, under LA, on 46 eyes (40 patients); 60.86% felt no discomfort with the LA, while 39.14 per cent felt some discomfort during the procedure. Rodriguez et al. Reference Rodriguez Navarro, Perez Mareno, Padilla Rodriguez, Cantos Gomez, Sanz Campillo and Marti Ascanio34 reported a study of loco-regional anaesthesia and sedation, as an alternative to GA, for DCR surgery in 20 patients, using Emla cream applied to the nasal mucosa, ropivacaine infiltration for anaesthetic block, and midazolam and fentanyl administered intravenously for sedation. The anaesthetic was described as good by 70 per cent of the patients and poor by only 5 per cent of the patients. In our study, endonasal endoscopic DCR conducted under LA was found to be acceptable to the majority (73 per cent) of patients. Dacrocystorhinostomy performed under LA has gained popularity for the treatment of adult patients. The acceptability of this technique may make LA the preferred anaesthetic in elderly and less well patients, and this increases the population that may benefit from such surgery.

Conclusions

Endoscopic endonasal DCR is now a well established, effective approach to relieve nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Our study suggested some differences in success, at 12-month follow up, between the laser and surgical groups; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance. Endonasal laser DCR had better results than endonasal surgical DCR at three months, but the surgical procedure had better results than the laser procedure at 12 months. It is possible that this reverse in symptomatic success over time indicates excessive fibroblastic activity in the laser group. Would this difference be more marked after more than one years' follow up? Longer term follow up may answer this question. Of note, eight patients randomised to receive endonasal laser DCR actually required additional surgical instrumentation in order to remove hard bone.

No statistically significant difference in symptom score improvement was found when comparing the following variables: LA vs GA; age over vs under 70 years; laterality; and operating surgeon. Change in symptom score was a useful indicator of symptomatic success.

Even though endonasal DCR does not match the high success rates of external DCR as reported in the literature, it does offer a chance of symptom resolution in the more elderly, the less fit, and in those wanting to avoid a facial scar. The endoscopic procedure has a low morbidity.

These results help to provide guidelines for counselling patients on the expected outcomes of endonasal surgical DCR and endonasal laser DCR.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr Helen Demetriou and the operating theatre staff of Gloucestershire Royal Hospital, without whose help this study would not have been possible.