Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a virus that causes a life-threatening disease known as coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). The World Health Organization declared Covid-19 a global pandemic on 11 March 2020.Reference Adil, Rahman, Whitelaw, Jain, Al-Taan and Rashid1 Transmission is facilitated primarily via respiratory droplets.Reference Wiersinga, Rhodes, Cheng, Peacock and Prescott2 Infection can be spread by asymptomatic, pre-symptomatic and symptomatic carriers of the virus. Otolaryngology groups are recommending that a higher level of personal protective equipment (PPE) should be used when performing aerosol-generating procedures (AGP).Reference Mick and Murphy3–Reference Thamboo, Lea, Sommer, Sowerby, Abdalkhani and Diamond6 This is because of the increased risk of infectious transmission secondary to high oral and nasal viral titres, and the unknown potential for aerosol generation during procedures.Reference Workman, Welling, Carter, Curry, Holbrook and Gray4 Tracheostomy and endotracheal suctioning especially can result in the spread of small aerosols containing viable pathogens.Reference Thamboo, Lea, Sommer, Sowerby, Abdalkhani and Diamond6

Children living with new or longstanding tracheostomies are a medically vulnerable group. This cohort of patients often have complex co-morbidities in addition to their need for an artificial airway. Care providers in hospitals and in the community are not always comfortable with managing these patients when they have acute presentations. In the current pandemic, there can be considerable apprehension from parents and caregivers about their child being more susceptible to the virus, fear about consequences of infection, and concern about navigating the healthcare system during periods of restricted access.Reference Kana, Shuman, Helman, Krawcke and Brown7,Reference Praud8

Healthcare workers are potentially at an increased risk of viral exposure and transmission when managing a patient with an open airway. Limiting the spread of all droplet-borne pathogens, not just SARS-CoV-2, is important, as the development of any respiratory tract symptoms can impact upon the medical workforce, and can have implications for close contacts of the patient and staff in these times. The AGPs often occur after hours or in emergency situations; they may also occur at peripheral hospitals, where access to specialist staff and support is limited. A clear team checklist and simple instructions may guide healthcare workers regarding when to perform AGPs in situations when Covid-19 status is unknown, suspected or confirmed, and can prepare them to perform AGPs safely. With written clarification, the proceduralists should feel confident and empowered to undertake AGP in a controlled manner, reducing the risks to the patient and the healthcare team.

This project was initiated when a paediatric patient had an incorrectly sized cuffed tube inserted in an emergency department in response to concerns about excessive aerosol generation from the tracheostomy tube and stoma whilst awaiting results for SARS-CoV-2 serology. Since that event, a simple Covid-19 emergency instruction plan was created for care providers that outlines management principles for this group of patients during the pandemic, to improve quality of care. It has been developed by the clinical nurse consultant for paediatric complex and artificial airways, in close collaboration with the otolaryngology department, the children's intensive care unit and the paediatric emergency department.

Our emergency management plan for these patients has several benefits. Firstly, it provides a clear algorithm to troubleshoot issues concerning the existing tube, to minimise air leak if SARS-CoV-2 infection is unknown, suspected or confirmed. Secondly, if the initial strategies are not sufficient, an approach is recommended to decrease the risk of patient morbidity from iatrogenic injury by identifying an appropriate alternative tracheostomy tube for the individual. Thirdly, a clear and structured plan is provided to minimise AGP risk to healthcare workers undertaking manipulation of the tracheostomy tube in these patients, to protect them from potential infectious exposure and allow the provision of expeditious care.

Materials and methods

The authors work at a large tertiary referral children's hospital located on a shared campus with a tertiary women's hospital that includes a neonatal intensive care unit, tertiary adult hospital and a private hospital that also has a special care unit for neonates. Ethics approval was not required for this project as it was a quality improvement proposal adapted from an existing hospital policy developed by the children's intensive care unit,9 with permission granted to modify it.

A three-document resource was developed for care providers managing paediatric patients with tracheostomies during the Covid-19 pandemic. Each document was only one page long and printed in colour, to make the key points identifiable and straightforward to read. It was written in plain language, to be easily understood by families, nursing, allied health and medical staff, irrespective of their background training in paediatric tracheostomy care provision.

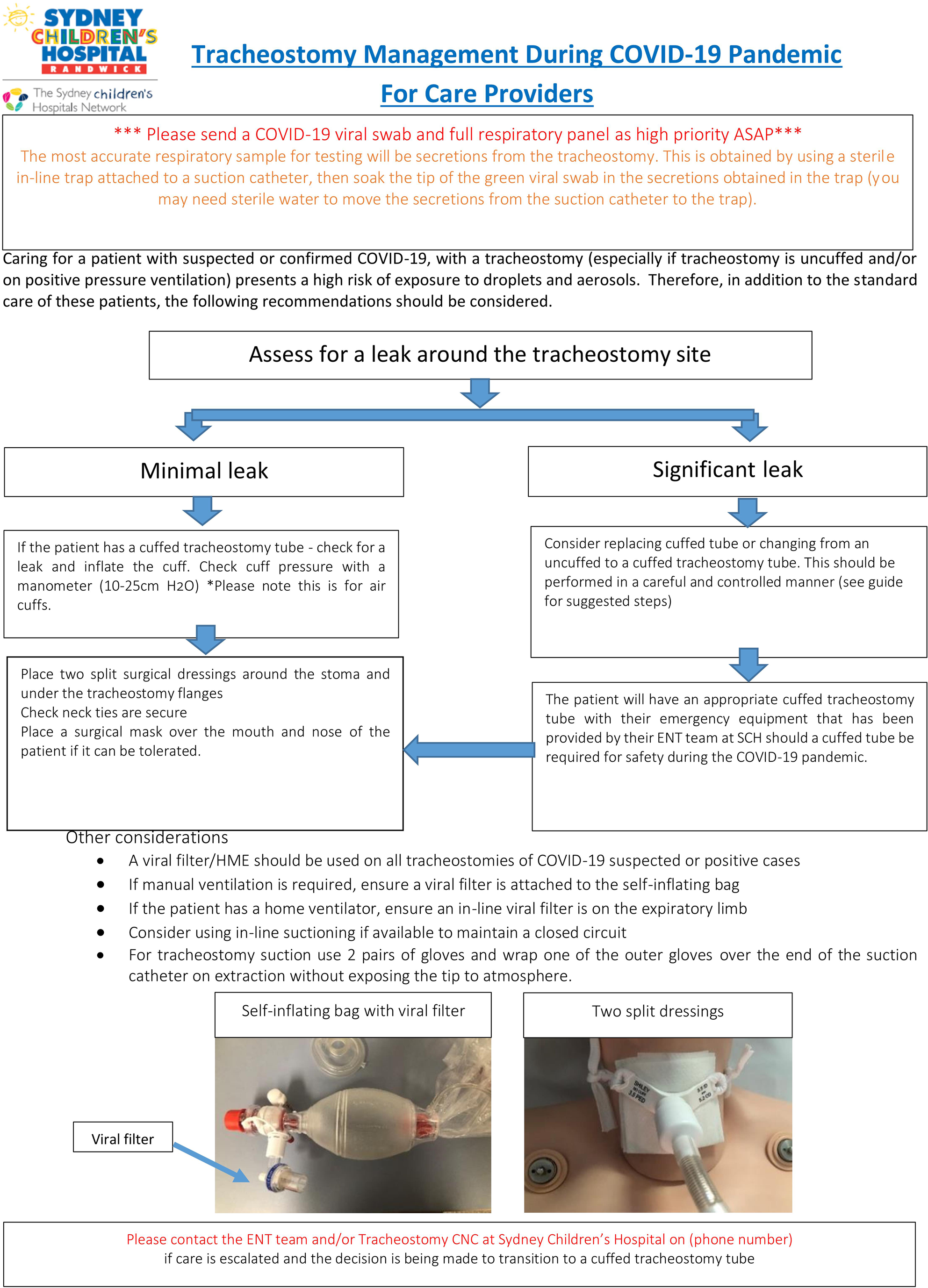

The first document, titled ‘Tracheostomy Management during COVID-19 Pandemic for Care Providers’, is a generic overview applicable to all patients in this group (Figure 1). When a patient presents for acute care, a Covid-19 viral swab and full respiratory panel should be collected for processing as a matter of urgency. Establishing positivity for Covid-19 in this cohort has implications for where the child should be managed and the appropriate levels of PPE that healthcare workers require. Respiratory secretions from the tracheostomy are adequate for sampling, and can avoid any distress associated with nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab collection.

Fig. 1. ‘Tracheostomy Management during COVID-19 Pandemic for Care Providers’ information sheet. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; ASAP = as soon as possible; H2O = water; SCH = Sydney Children's Hospital; HME = heat and moisture exchanger; CNC = clinical nurse consultant

Healthcare workers should be aware that there are water- and air-inflated cuffed tubes; in this plan, we refer to air-inflated cuffed tracheostomy tubes. If the patient has a cuffed tracheostomy tube, the cuff should be inflated to minimise any leak, and the cuff should be pressure checked. If there are concerns that the existing cuff is not functioning properly, consideration could be given to replacement with a cuffed tube in working order. Patients who use an uncuffed tube should also be assessed for a significant leak around the stoma. If this is identified, it may be appropriate to temporarily change to a pre-selected cuffed tube, in a careful and controlled manner. Once the leak has been reduced, two split surgical dressings are recommended to be placed around the stoma, and a surgical mask is placed over the mouth and nose of the patient if it can be tolerated. The use of appropriately sized viral filters based on weight and tidal volumes is advised for all tracheostomy patients during these presentations.

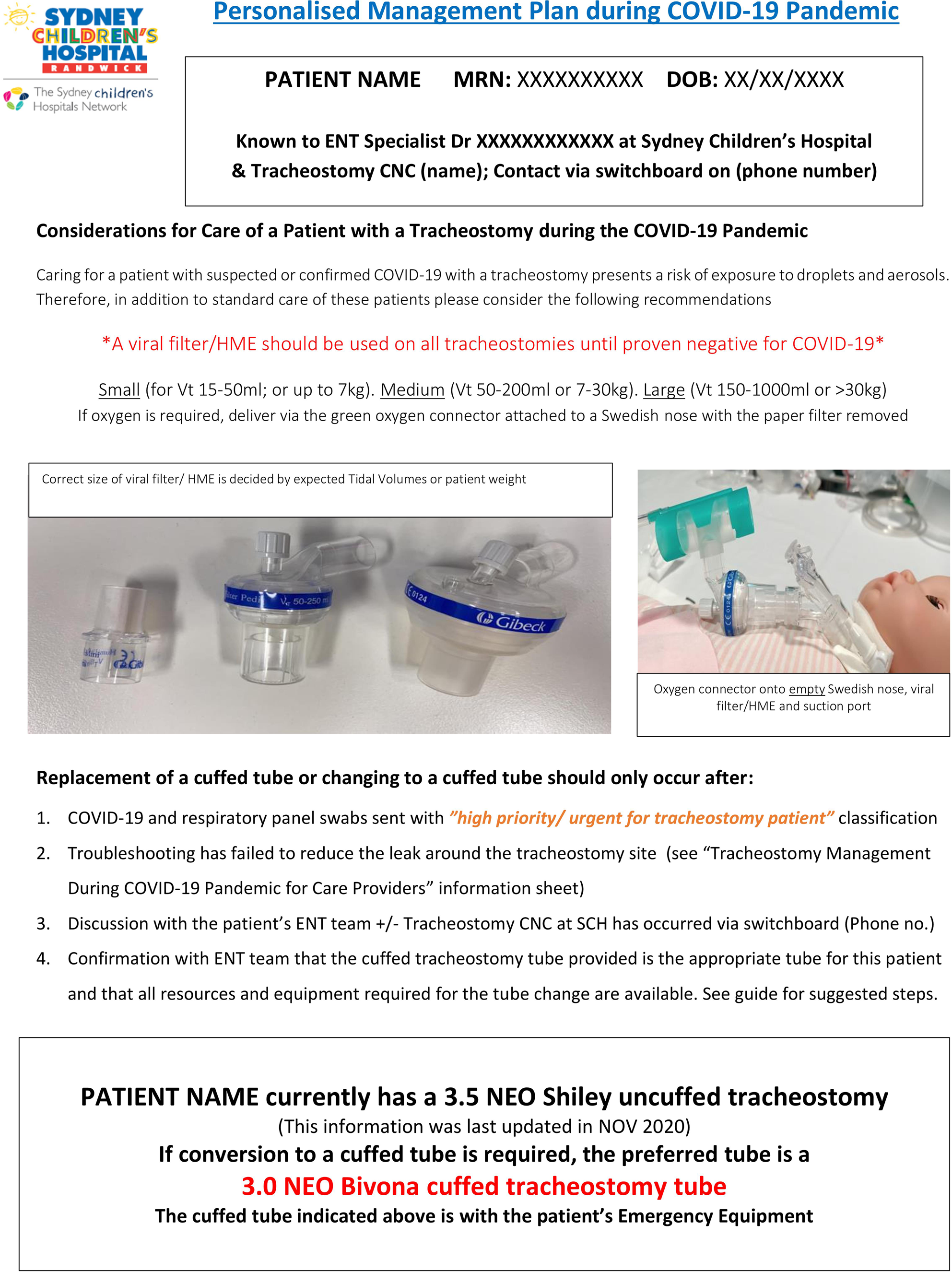

The second document, titled ‘Personalised Management Plan during COVID-19 Pandemic’, was designed to be customisable for the individual, and includes information about the current tracheostomy tube in use and any specific recommendations for change (Figure 2). This was necessary, as paediatric patients may have a particular size or type of tube in situ, chosen for specific reasons (e.g. unique anatomy, need for airway protection, requirement of long-term ventilation, or on a decannulation pathway). If there are concerns about excessive aerosol or secretion generation from the stoma around an uncuffed tracheostomy tube, it may be necessary in some circumstances to temporarily change to a cuffed tracheostomy tube. This is often not a straightforward swap from an uncuffed to an equivalent sized cuffed tube, as there are fewer cuffed tubes in paediatric sizes on the market, and they can be composed of various materials, with different lengths, outer diameters and angulation. Not all care facilities are expected to be stocked with such a range of tubes.

Fig. 2. ‘Personalised Management Plan during COVID-19 Pandemic’ form. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; MRN = medical record number; DOB = date of birth; CNC = clinical nurse consultant; HME = heat and moisture exchanger; Vt = tidal volume; SCH = Sydney Children's Hospital; no. = number; NOV = November

In order to generate the personalised plan, all paediatric patients with a tracheostomy currently being managed by our service were identified and reviewed. Demographics and details about their indication for tracheostomy, current tube size and type, status of the stoma, specific anatomical concerns, and need for long-term ventilation were collated. The primary otolaryngologist was consulted for each patient, to confirm individualised recommendations which avoid traumatising the stoma or the internal airway in the event that temporary change to an alternative tube was required. Each patient was given this pre-selected tracheostomy tube to keep in their emergency kit for such a situation.

The third document, titled ‘Changing a Paediatric Tracheostomy Tube for Suspected or Proven COVID-19 Infection’, entails the steps recommended to undertake changing a tracheostomy tube if required (Figure 3). The guide is intended to offer a systematic approach for care providers, once the decision to change the tracheostomy tube has been agreed upon by the treating specialists from our hospital. It covers team preparation, equipment preparation, patient preparation and the technique itself, with an emphasis on risk mitigation for both the patient and the staff involved.Reference Smith, Chen, Balakrishnan, Sidell, di Stadio and Schechtman10–Reference Pande, Bhalla, Myatra, Yaddanpuddi, Gupta and Sahoo12

Fig. 3. ‘Changing a Paediatric Tracheostomy Tube for Suspected or Proven COVID-19 Infection’ information sheet. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; CNC = clinical nurse consultant; SCH = Sydney Children's Hospital; PPE = personal protective equipment; BVM = bag valve mask; ETCO2 = end-tidal carbon dioxide

The tube change procedure should preferably be conducted in a negative-pressure single room, with full airborne precautions and PPE. Prior to commencing the procedure, the team should be assembled, the roles and steps of the intervention defined, the positioning of the patient and team members discussed, all equipment checked, drugs made available (if needed) and arranged in a way to ensure the procedure is performed efficiently, and escalation of emergency management made possible without the need to exit the negative-pressure room. Thus, access to suction, oxygen, monitoring equipment and waste disposal should be reviewed. Pre-medication may be considered in order to reduce patient anxiety, coughing and excessive movement. The parent or caregiver should be involved, as they are likely to be the most skilled at performing paediatric tracheostomy changes in their child. The second assistant aids in securing neck ties and positioning the new tube, whereas the third assistant manages sedation, and additional and emergency equipment as required. Having another person outside the room who can be easily contacted (e.g. via writing on a whiteboard, or speaking on a telephone or two-way radio transceiver (‘walkie-talkie’) checked prior to commencement) can be beneficial, as once wearing PPE within a confined space, it can be challenging to communicate with others outside if more help or items are needed.

The patient should have appropriate cardiorespiratory monitoring established, including end-tidal carbon dioxide (if available) during manipulation of the tracheostomy site. Inline suctioning should be prepared and ready to utilise for the tracheostomy tube, and oral suction catheters accessible if required. The patient should be pre-oxygenated for 5 minutes prior to the procedure and positioned to expose the tracheostomy. The tube change is then undertaken; once it has occurred, post-procedure airborne precautions are maintained for 15–30 minutes, as per the local hospital policies.

The family of each of our patients were contacted and educated about the Covid-19 emergency management plan, and their established personalised emergency tracheostomy kits were updated to include a hard copy of this new resource, with appropriate supplies provided if required. In addition, the caregivers were given an electronic copy of the resource, and the personalised management plan for each patient was uploaded to the hospital electronic medical records.

No direct financial support or grants were received for the conduct of this study. For those patients in whom a temporary change to a different type or size of tracheostomy tube was recommended, to reduce aerosol production, the tubes were supplied to the individuals by Enable NSW (a government department that provides assistive technology and related services to people with specific, short-term or ongoing health needs, to assist them to live safely at home; www.enable.health.nsw.gov.au).

Results

At present, our service manages 31 paediatric patients with tracheostomies (age range, 11 months to 17 years), in a variety of different care settings, though the majority (93.5 per cent) are cared for at home. Twenty-three patients (74.2 per cent) have an uncuffed tracheostomy tube in situ, and nine patients (29 per cent) require long-term ventilation.

Since the introduction of this initiative, there have been 10 presentations in which our Covid-19 emergency management plan has been actively utilised and has influenced care. On four occasions, the troubleshooting recommendations were followed successfully, without the need to escalate to a tube change. Six tube changes were undertaken, with a safe transition from an uncuffed tube to the individual's pre-selected cuffed tube, to minimise air leak. This included one patient on long-term ventilation who required intervention on three separate occasions. The cuffed tube remained in situ for these patients for an average of 4.3 days (range, 0.5–14 days) depending on the clinical condition of the child. There have been no incidents of stomal or airway injury during the insertion or removal of the temporary cuffed tube. Fortunately, none of our paediatric tracheostomy patients have been positive for SARS-CoV-2 to date. To the best of our knowledge, no patients have required tube changes outside of our protocol recommendations in their personalised plan.

Since the introduction of our management plan, the otolaryngology team and clinical nurse consultant have been contacted on multiple occasions when our paediatric patients with tracheostomies have presented to emergency departments around the state. Direct advice has been given, and risk reduction measures have been recommended and instituted early. Families have reported feeling more comfortable about their child's care whilst awaiting clearance for Covid-19. Feedback from healthcare professionals working in emergency departments to date has been overwhelmingly positive. An emergency department specialist at a peripheral hospital reported that one of our patients with the Covid-19 emergency plan was managed primarily by the parents as they had been well educated in this regard. Healthcare worker exposure was minimised and support from the tertiary ENT team was accessed quickly, which reduced local staff anxiety, and improved patient outcomes and patient flow. In this case, troubleshooting was effectively initiated based on the suggestions provided in our management plan, which aimed to reduce air leak around the tracheostomy tube whilst awaiting rapid Covid-19 testing results, such that the need for conversion to a cuffed tracheostomy cuffed tube was avoided.

Discussion

Children who require a tracheostomy as part of their management are a complex set of patients with increased medical needs. Respiratory tract illnesses in this group can have variable manifestations depending on: the pathogen involved, the child's immune status, underlying pulmonary disease and the ability to effectively manage secretions. The impact of Covid-19 on these patients is unknown, with only one reported case in the literature of hospitalisationReference Gün, Botan, Özdemir and Kendirli13 and of two children with milder illness.Reference Gray, Davies, Githinji, Levin, Mapani and Nowalaza14 Fortunately, the worldwide experience is of a generally less severe illness with a lower mortality rate in children than in adults overall. There are concerns, however, that as the adult population becomes vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, active infection and transmission will shift predominantly to the unvaccinated, which includes children aged under 12 years who have not been eligible to receive vaccination at this point in time.

An unwell child living with a tracheostomy will most likely present to the emergency department if their caregiver has concerns about their condition. Emergency departments are busy environments and, depending on the location of the hospital, may not have access to otolaryngology cover full time. Staff can have varying levels of experience and expertise in paediatric care. Tertiary hospitals usually have an abundance of resources to help within specific specialty fields, especially during normal working hours; however, even in large academic institutions, care providers can be unfamiliar and lack confidence with regard to tracheostomy management, more so in the paediatric population.Reference Ahmed, Yang, Deng, Bottalico, Matta-Arroyo and Cassel-Choudhury15 This can result in hastily made decisions that, though well-meaning in their intent, may introduce a risk for iatrogenic injuries to the child, and can unnecessarily increase aerosol generation, thereby potentially exposing healthcare workers.

The creation of our Covid-19 emergency management plan for paediatric tracheostomy patients was driven by the need for quality improvement, following an occasion when one of our patients had a larger tube inserted than appropriate for his airway in an attempt to reduce air leak and aerosol generation when they were coughing. We developed documents to provide a systematic approach and consistent advice about issues to consider. The resources enable delivery of care that is safe for both the patient and the healthcare provider, irrespective of their location, resources or time of presentation. The objective was not only to provide support, but to advance knowledge, improve communication and enhance quality of care.

The personalised management plan for each patient was formulated with careful consideration of the individual's requirements, taking into account their specific anatomy, indication for tracheostomy, co-morbidities, current tube dimensions and management. This was a consultative process between paediatric otolaryngology and the clinical nurse consultant, as tracheostomy tube nomenclature, branding, sizing, lengths and suitable conversion in the context of each patient's overall needs is highly specialised knowledge, especially in the infant population. Identifying how to troubleshoot issues concerning the existing tracheostomy tube in order to minimise air leak is emphasised as the first-line approach. Recognising the situations for when to change the tube, if at all, was intended to reduce the risk of immediate and longer-term damage to the stoma and airway from needless or panicked manipulation using an incorrect tube.

Tracheostomy tube change is not recommended as routine whilst awaiting Covid-19 clearance, given the potential high aerosol generation during the procedure; however, should the need outweigh the risk, then understanding the safest way to achieve it with the correct tube readily available makes the process as streamlined and time efficient as possible. In well-stocked tertiary hospitals that oversee complex paediatric patients, tracheostomy supplies may not be exhaustive or easy to locate from different departments after hours. Even if the equipment is in stock, it may not be the correct conversion size. When patients integrate a prescribed alternative tube into their usual emergency kit, they can facilitate efficient tube changing should the situation dictate, and minimise the risk of an incorrect tube or size being placed. Our project is a relatively low-cost initiative with multiple potential benefits for the child, their family and the health system in general.

Caregiver education about the plan, and provision of a temporary alternative tracheostomy tube to be used if appropriate, aimed to reduce anxiety and empower the carers, should they need to present to hospital with concerns about Covid-19 or other respiratory tract illness during the pandemic. In many instances, these families are fearful about: presenting to the emergency department, the risks of exposure for their child or themselves, and the potential need to change to a tube they had no experience with. The opportunity to explain and instruct carers about these anticipated issues was extremely valuable. Familiarity with emergency management enables improved overall care. In addition, a streamlined tube change, if required, reduces potential injury, and minimises the amount of time with a leaking cuffed or uncuffed tube in situ, whilst knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 status is pending.

• Paediatric tracheostomy patients are a medically vulnerable group

• Respiratory secretions and aerosols generated from an open airway can contain viral particles

• Healthcare workers are at increased risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection during aerosol-generating procedures

• Education of caregivers and healthcare workers can reduce risk of viral exposure during manipulation of tracheostomies

• A structured approach to decrease air leak may minimise risk of iatrogenic injury to paediatric tracheostomy patients

Coronavirus disease 2019 continues to have a significant impact on healthcare throughout the world. It is possible that new variants will evolve over time, creating ongoing challenges for the general population and healthcare workers. It is therefore reasonable to have an emergency management plan such as ours for vulnerable patients with artificial airways, to protect them and their care providers, particularly in the situation of droplet and aerosol transmitted infections. Our initiative has been shared with other tertiary children's hospitals in Australia in order to improve the care for all paediatric patients living with tracheostomies during uncertain times. The long-term benefits of this Covid-19 emergency management plan extend beyond the current pandemic, as the principles may be applied uniformly in the likely event of similar viral-based pandemics or outbreaks in the future.

Conclusion

A Covid-19 emergency management plan including a personalised recommendation for individual paediatric tracheostomy patients is presented for use in situations where SARS-CoV-2 infection status is unknown, suspected or confirmed. It has been designed to anticipate possible presentations, offer direction for troubleshooting, and guide the steps in management if escalation in care is required. It provides a framework to reduce the risk of viral transmission to healthcare workers performing AGPs on this cohort, and decreases unnecessary manipulation and potential damage to the patient's airway. These simple and relatively inexpensive measures can improve the quality of care delivery, with benefits to the patient, their families and the broader health system.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution from the children's intensive care unit and emergency departments at Sydney Children's Hospital, and from Enable NSW.

Competing interests

None declared