Introduction

The annual incidence of head and neck cancers is in the region of 550 000 cases worldwide.Reference Jemal, Bray, Center, Ferlay, Ward and Forman1 Survival rates have significantly improved over the last few decades.Reference Pulte and Brenner2 However, the overall survival rate remains in the region of 60 per cent.Reference Pulte and Brenner2 A proportion of patients may not be fit for primary radical treatment, often because of poor physiological fitness. In this group, palliative care is often given; however, such patients may not even be fit for chemotherapy or radiotherapy. In addition, in those patients with recurrent disease, palliative management remains a challenge, again as chemotherapy or radiotherapy have already been utilised. In both these groups, electrochemotherapy can be used as a palliative treatment option to control symptoms and achieve an improvement in quality of life. Therefore, electrochemotherapy appears to play a role in a select group of head and neck cancer patients requiring palliative care.

Electrochemotherapy is commonly used for primary basal cell carcinoma and primary skin squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and less commonly for non-skin-origin metastatic disease to the skin.Reference De Virgilio, Ralli, Longo, Mancini, Attanasio and Atturo3,Reference Campana, Testori, Curatolo, Quaglino, Mocellin and Framarini4 The technique of applying an electric field to the cells, electroporation, makes the cell membrane more permissible to normally non-permeable molecules. This approach has been in use for about 30 years.Reference Mir, Orlowski, Belehradek and Paoletti5–Reference Plaschke, Gothelf, Gehl and Wessel7 Cytotoxic drugs, such as bleomycin, are poorly permeant to cancer cells, but the addition of electroporation significantly enhances their uptake and tumour response. Bleomycin exerts high cytotoxicity when internalised, and therefore the technique of electrochemotherapy has great potential. It was demonstrated that, on average, 200 internalised molecules of bleomycin are sufficient to kill cells. Bleomycin induces single and double DNA strand breaks. Bleomycin cytotoxicity after electroporation can be potentiated up to 700 times.Reference Sersa, Cemazar and Rudolf8

The International Network for Sharing Practice in ElectroChemoTherapy (‘INSPECT’) group has provided detailed guidance on the use of electrochemotherapy.Reference Mir, Gehl, Sersa, Collins, Garbay and Billard9,Reference Gehl, Sersa, Matthiessen, Muir, Soden and Occhini10 In 2013, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) supported and produced guidance on the use of electrochemotherapy for metastatic tumours of non-skin-origin and melanoma.11 Despite this, the use of electrochemotherapy in the treatment of metastatic head and neck cancer in the UK appears to be infrequent.

This paper shares our experience of electrochemotherapy in selected non-skin-origin metastatic malignancies in the head and neck region. We also attempted to explore the current practice of electrochemotherapy in the UK, having conducted a national survey.

Materials and methods

A prospective database collated between April 2016 and May 2019 was reviewed. Only non-skin-origin metastatic malignancies in the head and neck region were included. Medical records were reviewed and clinical information (age at diagnosis, gender and tumour–node–metastasis (TNM) classification) was collected. Location of disease and indications for treatment were assessed. Survival length, patient benefit and complications arising from electrochemotherapy were also recorded.

Separately, an electrochemotherapy user list was obtained from IGEA Medical (IGEA, Carpi, Italy) in order to conduct the national survey. Currently, only IGEA Medical produces electrochemotherapy equipment, allowing us to identify all UK users. Registered clinicians who are involved in the management of head and neck malignancies were contacted via e-mail. Other users, for example, those treating gynaecological malignancies, were not contacted.

The survey aimed to identify how many of the head and neck multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) offer electrochemotherapy as a palliative treatment option for patients. A reminder e-mail was sent to non-responders after two weeks. In the e-mail, two questions were asked: (1) Do you offer electrochemotherapy for non-cutaneous metastatic malignancy in the head and neck region?; and (2) If your answer to question 1 is ‘yes’, how many head and neck MDTs are you providing your service to?

Electrochemotherapy techniques

Electrochemotherapy is performed under either general anaesthesia (GA) or local anaesthesia (LA) with sedation, with a preference for the latter as a day-case procedure.

In all cases, bleomycin is injected directly into the non-skin-origin metastatic disease; however, it can be given as an intravenous infusion in patients with extensive disease. Following bleomycin administration, a specific electrode is inserted into the tumour tissue and an electrical pulse is applied. There is a choice of three electrode types depending on the thickness and size of the tumour being treated. Increased uptake of bleomycin only occurs in the electroporated tissue. This facilitates targeted treatment and minimises side effects in the surrounding healthy tissues.

Following treatment, a simple dressing is applied. The patients who receive LA with sedation are discharged after 2 hours of observation, with a 4-hour observation period in the GA group. All patients are reviewed as out-patients after a period of four to six weeks.

Results

During the study period, five patients received electrochemotherapy. They were all male, with ages ranging from 42 to 79 years. All patients were given electrochemotherapy as a palliative option, to facilitate disease control and improve quality of life.

Three patients had recurrent disease following chemoradiotherapy and therefore had a limited choice of other palliative treatment options. Of these three patients, two had non-skin SCC and one had an esthesioneuroblastoma. The fourth patient, with SCC of an unknown primary, declined standard primary treatment and opted for palliation. The final patient had metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma in the larynx, with bleeding from metastatic disease around his tracheostomy site. The locations of the primary disease and TNM staging are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics and clinical details

Pt. no. = patient number; TNM = tumour–node–metastasis; ECT = electrochemotherapy; mth = months; M = male; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma; n/a = not applicable

Although this treatment aimed not to prolong life but to improve the quality of life in the palliative setting, survival varied greatly. The patient with cancer of an unknown primary unfortunately died one month following treatment. His metastatic skin disease prior to electrochemotherapy was very symptomatic. The necrotic tissue involving neck nodes and skin would get infected and bleed regularly, and this required frequent topical treatment and dressings, as well as admissions for antibiotics. Following electrochemotherapy, the frequency of his infections and bleeding greatly reduced, allowing him to be managed at home where he could spend more time with his family. This improved symptomatology, providing a more comfortable and dignified end-of-life experience.

Two other patients, both with recurrent metastatic SCC following previous treatment with chemoradiotherapy, survived for three and seven months respectively. Both patients reported similar symptomatic and quality-of-life benefits following treatment with electrochemotherapy: one had significant neck nodal tissue shrinkage and the other had control of recurrent bleeding from skin involvement.

The other two patients remain under follow up following electrochemotherapy. The first patient underwent treatment two months prior to writing, for metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma that had metastasised to the larynx and tracheostomy site. He had recurrent bleeding around the tracheostomy site and received electrochemotherapy directly into this area. Since this treatment, there have been no further issues with bleeding at this site, but the patient remains under close follow up. Again, this has facilitated management of the patient in an out-of-hospital setting.

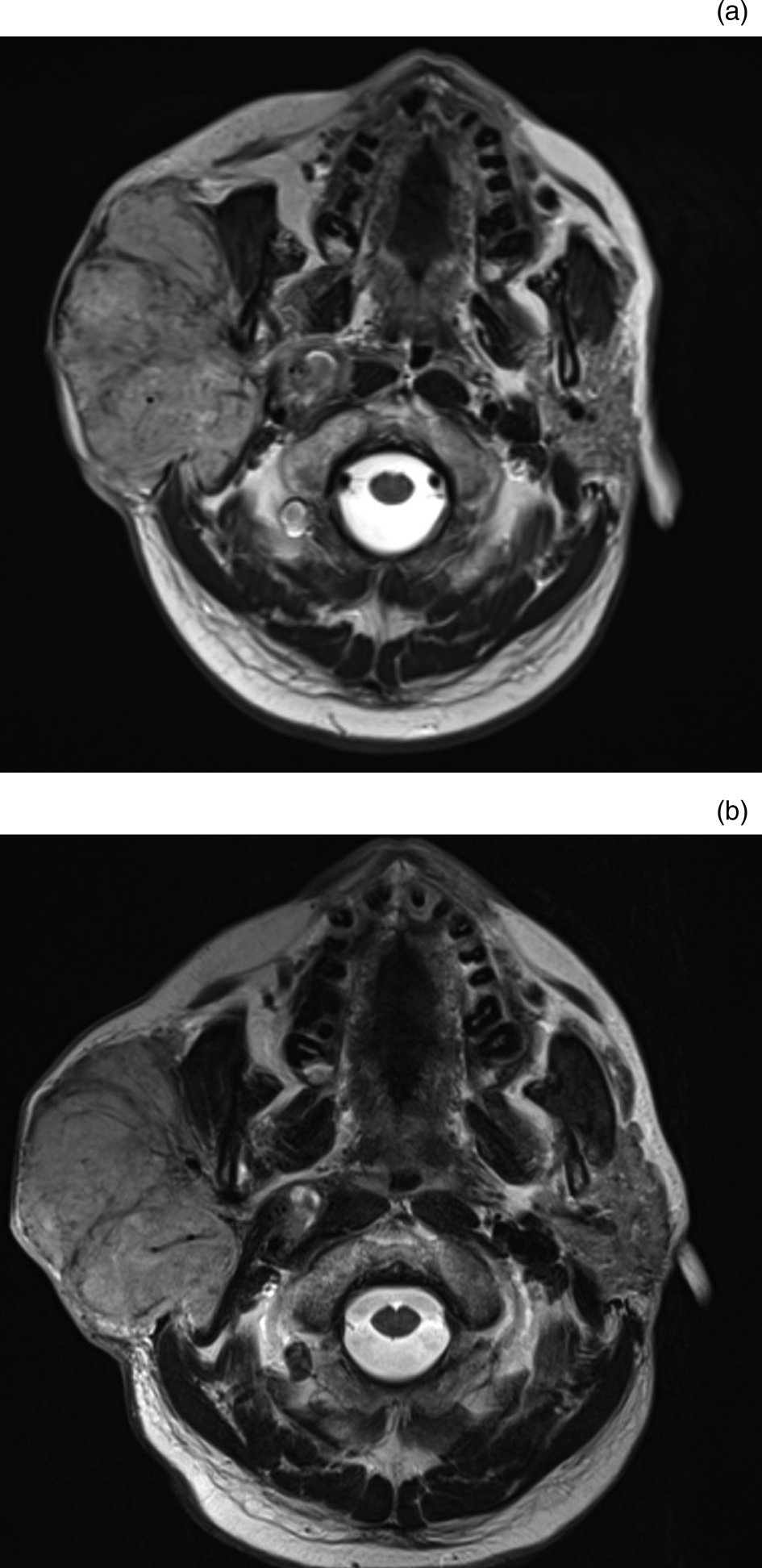

The second patient currently under follow up had recurrence of an esthesioneuroblastoma in the right side of the neck following chemoradiotherapy to the skull base. Prior to treatment with electrochemotherapy, the patient's right-sided neck mass was rapidly enlarging, and causing quite significant pain and distress. After treatment with electrochemotherapy, the rate of nodal tumour growth has slowed significantly, to the point where the disease has been stable for over two years (Figures 1 and 2). The patient's pain was better controlled, thereby improving his overall quality of life.

Fig. 1. Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scans of the neck showing stable disease between December 2016 (a) and May 2019 (b), with a right-sided neck mass measuring 7.5 cm × 5 cm and 8.5 × 5.5 cm respectively following electrochemotherapy.

Fig. 2. Clinical photographs showing stable right-sided neck disease pre-electrochemotherapy (a) and post-electrochemotherapy (b), six months apart. Published with patient's permission.

Complications were rare and minor, with only two patients reporting any side effects of the treatment. The first patient, who received electrochemotherapy for nodal recurrence of a supraglottic SCC following chemoradiotherapy, had mild facial swelling which resolved spontaneously within a few days of treatment. In the second patient, who had recurrence of an advanced oropharyngeal SCC following chemoradiotherapy, with significant involvement of the neck skin, substantial skin ulceration was also observed post-treatment. However, this was anticipated pre-operatively and a planned split skin graft was arranged shortly after treatment, which has subsequently healed effectively. The details are summarised in Table 1.

National survey results

Thirty-seven registered UK users of electrochemotherapy were identified. Eight were excluded because they do not treat head and neck cancer patients. The survey was distributed to the remaining 29 users. Responses were received from 16 users (55 per cent); however, this only represented 13 (72 per cent) of the hospitals listed as having an electrochemotherapy user, as some institutes have more than 1 registered user. Of those users that responded to the survey, some provide their service for more than one MDT. Overall, we identified that only 15 of the 69 UK head and neck cancer MDTs (22 per cent) offer an electrochemotherapy service.

Discussion

Our series indicates that electrochemotherapy is a safe and effective palliative treatment adjunct in certain head and neck cancer patients, especially when other treatment options such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy have already been utilised as a primary treatment. Complications were infrequent and well tolerated. The main benefit of electrochemotherapy was an improvement in patients’ quality of life and the reduction of symptoms. This allowed patients to spend more time in an out-of-hospital setting closer to their families during the palliative period of their life. Despite the limited numbers in our case series, electrochemotherapy shows great promise, particularly in this subgroup of patients who otherwise have limited treatment options. Unfortunately, however, use of electrochemotherapy in the UK is infrequent, as demonstrated by our survey, with only 22 per cent of UK MDTs offering the service.

Our study, although limited in terms of numbers, demonstrated similar results to other published studies. All our patients appeared to show a response to the treatment, with an improvement or slowing in the progression of nodal growth, or a reduction in symptoms such as bleeding.

The recently published phase II Danish Head and Neck Cancer group's ‘DAHANCA 32’ trial study, on electrochemotherapy for recurrent mucosal head and neck cancer, has shown a response rate of 58 per cent in local recurrent head and neck cancer.Reference Plaschke, Johannesen, Hansen, Hendel, Kiss and Gehl12 Another multi-centre phase II observational study by Plaschke et al.Reference Plaschke, Bertino, McCaul, Grau, de Bree and Sersa13 showed a similar response rate of 56 per cent. In these two studies, electrochemotherapy was offered to patients when standard treatment for mucosal head and neck malignancy was not a viable option, or when patients declined standard treatment. For diseases of various other histological subtypes that involve the skin, the response rate with electrochemotherapy is in the region of 80 per cent.Reference Campana, Testori, Curatolo, Quaglino, Mocellin and Framarini4,Reference Marty, Sersa, Garbay, Gehl, Collins and Snoj14 A systematic review by Lenzi et al.Reference Lenzi, Muscatello, Saibene, Felisati and Pipolo15 reviewed 14 eligible studies and recommended consideration of electrochemotherapy in the palliative setting.

These published studies concluded that electrochemotherapy was well tolerated by patients, mirroring our experience. Post-treatment swelling needs specific attention, in particular when the treatment area is in the oropharynx, larynx and/or hypopharynx. Tracheostomy is required in some cases.Reference Plaschke, Johannesen, Hansen, Hendel, Kiss and Gehl12

Electrochemotherapy is now a more established treatment of primary skin cancer and cutaneous metastases. Despite the growing popularity of electrochemotherapy, not many head and neck MDTs offer this treatment. Perhaps electrochemotherapy is less well known to UK head and neck MDTs, and more work needs to be done to raise awareness of its existence and use. Although NICE published guidance on the use of electrochemotherapy, and concluded that it may reduce symptoms and improve quality of life for appropriately selected patients, it is not currently mentioned in the 2016 UK head and neck cancer multidisciplinary guidelines.Reference Paleri and Roland16 There is also increasing evidence supporting the use of electrochemotherapy for internal organs, and for mucosal head and neck cancer. An updated guideline is anticipated in the near future.Reference Gehl, Sersa, Matthiessen, Muir, Soden and Occhini10

• Electrochemotherapy is recommended for managing metastatic head and neck disease of non-skin origin

• International Network for Sharing Practice in ElectroChemoTherapy (‘INSPECT’) group give detailed guidance on electrochemotherapy use

• Electrochemotherapy can provide local control of disease in the palliative setting when standard treatments cannot be given

• This treatment can improve symptoms and quality of life at the end-of-life period

• All UK head and neck multidisciplinary teams should be made aware of electrochemotherapy as an option

• Ongoing research is investigating the expanding role of electrochemotherapy, which may require multi-centre collaboration

Another issue may be that the setup of electrochemotherapy services varies between different regions and hospitals. The surgeon who provides electrochemotherapy might not be a core member of the head and neck MDT. In that scenario, core members should be aware that electrochemotherapy can be a palliative option in a selected group of patients and consider the need for referral to an electrochemotherapy service provider. There are a number of registered electrochemotherapy units across the UK and access to electrochemotherapy should not pose a significant problem.

Conclusion

Electrochemotherapy appears to be a well-tolerated and safe adjunct to standard palliative treatment options for non-skin-origin head and neck metastatic disease, particularly when chemotherapy or radiotherapy is not a viable treatment option. It is most effective at controlling local disease in the head and neck region in order to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life in the palliative care setting.

However, electrochemotherapy is only offered by a limited number of MDTs in the UK and there may be room for expansion. In addition, further evidence from randomised trials is needed to support its use. As the sample size tends to be small, a multi-centre collaborative approach would be necessary. There is also a growing interest in the combination of electrochemotherapy and immunotherapy.Reference De Virgilio, Ralli, Longo, Mancini, Attanasio and Atturo3,Reference Plaschke, Johannesen, Hansen, Hendel, Kiss and Gehl12 Future research is needed to examine its expanding possibilities in order to enhance patients’ palliative treatment.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank IGEA Medical UK for providing access to the electrochemotherapy site register.

Competing interests

None declared