Introduction

Endoscopic endonasal approaches for skull base lesions have been extensively developed as part of the evolution towards minimally invasive surgery. Endoscopic endonasal approaches have widened and expanded beyond the treatment of lesions of the sella and parasellar areas, extending sagittally from the cribriform plate up to the clival region. However, endoscopic endonasal approaches for skull base tumours require extensive manipulation of the nasal corridor, especially for those procedures that require multi-layered reconstruction of the skull base defect.

A wide sinonasal corridor is important for adequate exposure of the surgical field and for instrumentation needed to facilitate the safe excision of the tumour. This extensive manipulation results in significant post-operative sinonasal morbidity. Awad et al.Reference Awad, Mohyeldin, El-Sayed and Aghi1 reported nasal crusting as the most common symptom (50.8 per cent) experienced after an endoscopic endonasal approach, followed by nasal discharge (40.4 per cent), nasal airflow blockage (40.1 per cent) and olfactory disturbances (26.7 per cent). The frequent use of nasal lavages to clean the nasal cavity is an accepted practice, to lessen morbidity.Reference Balaker, Bergsneider, Martin and Wang2

Nasal lavage is a simple, inexpensive and long-established method for treating a variety of nasal and sinus conditions, such as rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis, and for managing post-operative patients. It is easy to perform, and seems to improve nasal symptoms and, subsequently, post-operative quality of life (QoL). Nasal lavage acts by mechanically cleansing crusting and reducing mucociliary transit time; thus, it improves the mucociliary clearance of the sinonasal tract.Reference Talbot, Herr and Parsons3 Crusts and thick secretions, which are common after surgery, become soft and less adherent with nasal irrigations.Reference Brown and Graham4 This helps with the nasal debridement performed in out-patient clinics during follow up.

Mupirocin is produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens, and works by inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis via binding reversibly to bacterial isoleucyl-tRNA-synthetase.Reference Hudson5 It has previously been used as a treatment and as a prophylaxis for Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriers. Its antibacterial spectrum includes Gram-positive micro-organisms such as S aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae. In addition, it shows antibacterial properties against certain Gram-negative organisms, such as Haemophilus influenza, Moraxella catarrhalis and neisseria species.Reference Sutherland, Boon, Griffin, Masters, Slocombe and White6 Therefore, it covers the common causative micro-organisms responsible for infections of the nasal cavities. Mupirocin can be affected by pH, and it has been suggested that it may be more active in acidic pH. However, a recent pharmaceutical study determined that mupirocin is stable, and does not show any degradation in either acidic or alkaline environments.Reference Manoharan7 No study has yet been conducted on the outcome of mupirocin nasal lavage in patients who have undergone an endoscopic endonasal approach in whom the nasal mucosa is not injured.

Materials and methods

This pilot randomised, controlled trial aimed to evaluate the effects of adding mupirocin to nasal lavages on nasal symptoms and endoscopic findings in patients who have undergone endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery.

The sample size was calculated and estimated based on research by Uren et al.,Reference Uren, Psaltis and Wormald8 which studied the outcome of nasal lavage with mupirocin in patients with surgically recalcitrant chronic rhinosinusitis. In that study, the sample size was 16 patients and all the study patients were given nasal lavage with mupirocin.

Sample size is calculated with the formula shown below, where: n1 = sample size of group 1; n2 = sample size of group 2; σ1 = standard deviation of group 1; σ2 = standard deviation of group 2; Δ = difference in group means; κ = ratio of n2/n1; z1-α/2 = two-sided Z value (e.g. z = 1.96 for 95 per cent confidence interval); and z1-β = power.

The sample size required for this study was calculated based on the difference in pre- and post-treatment Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT) scores and standard deviations reported in a paper by Uren et al.,Reference Uren, Psaltis and Wormald8 using the above formula. At the time of this study, the total number of endoscopic skull base surgical procedures performed in Sarawak General Hospital was about twenty cases a year. Therefore, all patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria who presented at this centre during the study period were included, with an estimated total number of about 20 patients.

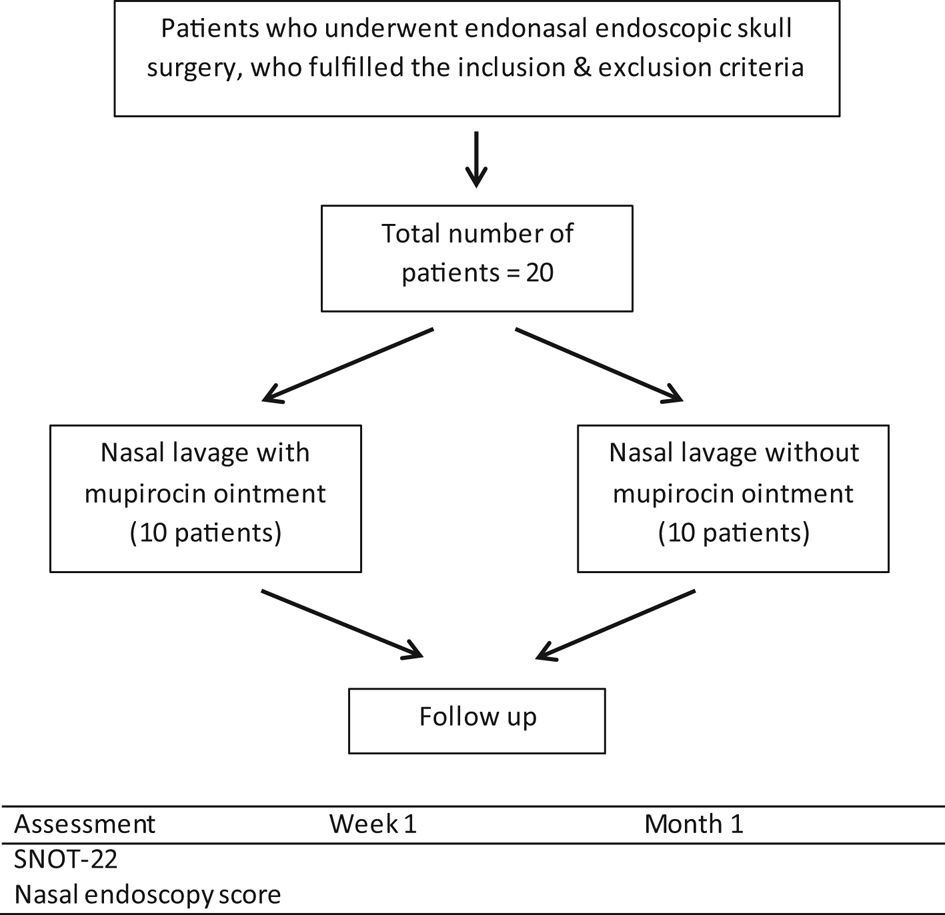

Patients who underwent endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery at Sarawak General Hospital during the period from 1 August 2016 to 31 July 2017, and who met the inclusion criteria, were randomised into two groups (Figure 1). Randomisation was carried out in blocks of four, wherein odd numbers represented nasal lavage with mupirocin, while even numbers represented nasal lavage without mupirocin. This was to ensure that the groups were balanced periodically. An assistant (nurse), who was not involved in the study, performed the randomisation and labelled the bottles according to the randomised numbers.

Fig. 1. Study flowchart. SNOT-22 = 22-item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test

The inclusion criteria were: age of 18 years or older, an adequate indication for endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery, able to understand the instructions and to attend follow-up appointments at the otolaryngology out-patient clinic, and able and willing to consent to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria included: age below 18 years, allergy or hypersensitivity to mupirocin, previous sinonasal pathology, previous sinonasal surgery, revision surgery for skull base tumour, and refusal to participate in the study.

Patients were educated on the techniques of nasal lavage, and a commercially available 250 ml nasal lavage plastic squeeze bottle was provided to both groups. The control group was instructed to use an alkaline nasal lavage. The study group was instructed to use an identical solution, but with the addition of one finger-tip unit of mupirocin ointment, which is approximately 0.5 g. Nasal lavages were self-performed three times a day for a month, in both groups.

Patients were examined during out-patient visits at one week and one month post-operatively. Specifically, patients were assessed regarding their nasal symptoms using the 22-item SNOT questionnaire, and examined endoscopically by an otolaryngologist using the nasal endoscopy score (Lund–Kennedy endoscopic score); the otolaryngologist was blinded to the patients’ pathology, surgery and SNOT-22 questionnaire results.

Results

A total of 20 patients (11 women and 9 men), with ages ranging from 19 to 73 years, participated in the study. Nine of the patients were Chinese, six were Ibans and five were Malays. Patients were randomised into 2 groups, with 10 patients in both the mupirocin and non-mupirocin nasal lavage groups.

The most common indication for surgery (Figure 2) was the presence of a symptomatic pituitary adenoma, followed by cerebrospinal fluid leak repair, sellar meningioma and clival tumour. Other indications included craniopharyngioma, olfactory neuroblastoma, recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma with infratemporal extension, metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma, Rathke's cyst, and nasal rhabdomyosarcoma.

Fig. 2. Diagnostic indications for surgery. NPC = nasopharyngeal carcinoma; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid

Table 1 shows the mean and median scores for the SNOT-22 questionnaire and for nasal endoscopy at one week and one month following surgery. The independent sample t-test and Mann–Whitney U test were used to compare the groups.

Table 1. SNOT-22 and nasal endoscopy scores at one week and one month post-operatively

*Median (interquartile range) values. Group values were compared using the †Mann–Whitney U test or ‡independent sample t-test. SNOT-22 = 22-item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test; SD = standard deviation

The SNOT-22 scores (Figures 3 and 4) at one week were slightly higher in the mupirocin nasal lavage group (average score of 10.5; interquartile range, 10.25) compared to the non-mupirocin group (average score of 10.00; interquartile range, 13.75). The p-value was 0.470, demonstrating no statistical significance. Scores for patients in the mupirocin nasal lavage group were lower (average score of 4.70; interquartile range, 5.50) than those in the non-mupirocin nasal lavage group (average score of 8.80; interquartile range, 9.00) at one month. This difference, however, was not statistically significant (p = 0.123).

Fig. 3. Sino-Nasal Outcome Test 22 (SNOT-22) scores at one week post-operatively.

Fig. 4. Sino-Nasal Outcome Test 22 (SNOT-22) scores at one month post-operatively.

Patients in the mupirocin nasal lavage group demonstrated greater improvement endoscopically (lower nasal endoscopy scores), both at one week and one month. Figures 5 and 6 demonstrate that patients in the mupirocin nasal lavage group had lower nasal endoscopy scores (mean score = 5.20; interquartile range, 2.00) than those in the control group (mean score = 6.40; interquartile range, 1.00) at one week (p = 0.007). The results were similar at one month, with the mupirocin nasal lavage group demonstrating a superior (lower) mean score (2.30; interquartile range, 0.75) than those in the non-mupirocin nasal lavage group, with the latter having a mean score of 4.60 (interquartile range, 1.25; p < 0.001).

Fig. 5. Nasal endoscopy scores at one week post-operatively.

Fig. 6. Nasal endoscopy scores at one month post-operatively (showing outliers).

The SNOT scores in the mupirocin group (Table 2) showed a larger difference between one week and one month compared to the non-mupirocin group. Nasal endoscopy scores followed a similar trend, showing greater significant improvement in the mupirocin nasal lavage group compared to the non-mupirocin nasal lavage group at one week and at one month.

Table 2. Comparison of SNOT-22 and nasal endoscopy scores at one week versus one month

Time-point values were compared using the *Wilcoxon signed rank test or the †paired t-test. SNOT-22 = 22-item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test

Discussion

Topical antimicrobials are an accepted treatment for managing sinonasal infection. Topical antimicrobials have the advantage of acting directly on sinonasal mucosa, providing a higher concentration at the targeted site.Reference Lim, Citardi and Leong9 Unlike systemic antibiotics, topical administration is effective against bacterial biofilms. A study by Ha et al.Reference Ha, Psaltis, Butcher, Wormald and Tan10 demonstrated that mupirocin can reduce biofilm mass by more than 90 per cent. Similar results were noted by Desrosiers et al.,Reference Desrosiers, Bendouah and Barbeau11 who demonstrated that topical antibiotics provide the required concentration to eliminate bacteria in biofilms.

Most patients undergoing skull base surgery are not affected by diseases that produce changes in nasal mucosa, which is the opposite for patients undergoing endoscopic surgery for sinonasal inflammatory disease. However, disruption of the normal physiology of the nasal mucosa during surgery leads to sinonasal morbidity that is prevalent following an endoscopic endonasal approach.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to address the effects of using mupirocin nasal lavages after skull base surgery. Improvements in SNOT-22 and nasal endoscopy scores at one month compared to one week were noted in both the mupirocin and non-mupirocin nasal lavage groups. However, the mupirocin group showed lower scores for both the SNOT-22 and the endoscopy assessment at one month (i.e. greater improvement). This suggests that nasal symptoms and nasal endoscopy scores, which are worse in the immediate post-operative period, improve more and faster with the mupirocin nasal lavage, although patients were treated and followed for one month only.

Our results compare favourably with those of Uren et al.,Reference Uren, Psaltis and Wormald8 who used mupirocin nasal lavage in patients with surgically recalcitrant chronic sinusitis, yielding promising results. In Uren's study, patients were treated with nasal lavage with mupirocin twice a day for three weeks and were then assessed endoscopically, and using the SNOT-20 questionnaire and nasal endoscopy score. Endoscopic findings were graded for crusting, discharge, mucosal oedema and erythema. The study showed improved nasal endoscopic findings in 15 of 16 patients, and improved overall nasal symptoms in 12 of 16 patients in the study.

In a study by Jervis-Brady et al.,Reference Jervis-Brady, Boase, Psaltis, Foreman and Wormald12 on surgically recalcitrant staphylococcal-associated chronic rhinosinusitis, significant improvements were shown in nasal symptoms and endoscopic scores after 28 days of using a mupirocin sinonasal rinse, which is similar to the results of our study. The nasal cavity, which was S aureus culture negative immediately after treatment, was also found to be negative at one month in 88.9 per cent of patients in that study who were using the mupirocin sinonasal rinse. These improvements, however, become less apparent as time progressed (two to six months after treatment). This would suggest that mupirocin nasal lavages have a significant primary benefit in the immediate post-treatment period.

The rate of resistance in topical mupirocin is low. In a study by Raz et al.Reference Raz, Miron, Colodner, Staler, Samara and Keness13 investigating the prevention of recurrent staphylococcal infection using nasal mupirocin, 17 out of 34 patients were given a 5-day course of mupirocin every month for a year, while the remaining patients were given only a 5-day course. The incidence of nasal colonisation was lower in the long-term mupirocin patients, with only one patient (2.9 per cent) developing resistance.

In another study by Jervis-Brady et al.,Reference Jervis-Brady and Wormald14 on patients with surgically recalcitrant chronic rhinosinusitis, the resistance rate was similarly low, at 2.4 per cent. That study, however, showed a high recolonisation rate (73.7 per cent), which suggests that complete eradication of S aureus and the maintenance of nasal sterility after stopping mupirocin is difficult, given the varied anatomy of the nasal cavity and the inability of the nasal lavage to completely reach all areas of the nasal cavity. A negative swab culture does not mean that the micro-organisms are eliminated, as the risk of recolonisation is high once mupirocin is stopped. Mupirocin nasal lavage, therefore, plays an important role during the immediate post-operative period, when the risk of complications such as flap failure, cerebrospinal fluid leaks and infection are highest, and may lead to significant sinonasal morbidity with high SNOT-22 and nasal endoscopy scores.

Sinonasal morbidity following endoscopic skull base surgery affects patients’ QoL. McCoul et al.Reference McCoul, Anand, Bedrosian and Schwartz15 assessed the QoL in a series of 85 patients, at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 6 months and 1 year after undergoing endoscopic anterior skull base surgery. Patients showed the greatest sinonasal morbidity and highest SNOT-22 questionnaire scores at three weeks after surgery. This is probably because of the effects of endonasal surgery, leading to intranasal oedema, crusting and nasal discharge. Patients’ QoL improved, correlating with a lower SNOT score, towards the end of the study at one year post-surgery.

Similar results were noted in a paper by Pant et al.,Reference Pant, Bhatki, Snyderman, Vescan, Carrau and Gardner16 wherein patients showed improvements in SNOT-22 scores at 6–12 months after surgery. de Almeida et al.,Reference de Almeida, Snyderman, Gardner, Carrau and Vescan17 in a prospective study of a cohort of 63 patients, reported that it takes about 101 days for the nasal crusting to resolve, even longer in complex cases, and that nasal crusting (98 per cent) and nasal discharge (46 per cent) were the most common post-operative symptoms. The present study shows that patients who used mupirocin nasal lavage had lower SNOT-22 and nasal endoscopy scores than those who did not, suggesting that their sinonasal morbidity was reduced by this method.

A study by Carr et al.Reference Carr, Hill, Chiu and Chang18 on topical antibiotic nasal lavage concluded that topical antibiotics can alter the microbiological culture results of the nasal cavity. However, their study comprised patients with recalcitrant rhinosinusitis, and the mean duration of nasal lavage usage was six weeks. In our study, the patients’ nasal cavity and sinuses were not diseased, and the duration of topical mupirocin nasal lavage use was only four weeks.

Side effects of mupirocin may include signs and symptoms of irritation, such as itching, congestion or erythema. In this study, none of the patients who used mupirocin nasal lavage complained or reported any such side effects. No side effects were reported in other studies using mupirocin either.Reference Raz, Miron, Colodner, Staler, Samara and Keness13,Reference Kauffman, Terpenning, He, Zarins, Ramsey and Jorgensen19 This suggests that mupirocin is safe for use as an additive in nasal lavage, with little or no side effects.

• Endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery is becoming more common, but is associated with high sinonasal morbidity

• Sinonasal morbidity affects patients’ quality of life post-surgery

• This article describes a new, effective method for reducing sinonasal morbidity following endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery

• Nasal lavage with mupirocin improved sinonasal outcomes, with better Sino-Nasal Outcome Test 22 and nasal endoscopy scores

There are some limitations to this study. Nasal lavage application was self-performed by the patients, and their technique was assumed to be correct and effective. Expected variation in the methods of nasal lavage use may have an immeasurable effect on the results. Another potential flaw is that the follow-up period for the study was only one month. A longer follow-up period could determine differences in long-term sinonasal outcomes associated with the different nasal lavages.

Conclusion

This study, with a level of evidence of 1B, suggests that, in patients undergoing endoscopic skull base surgery, mupirocin nasal lavage use improves outcomes in terms of sinonasal morbidity.

Competing interests

None declared