Introduction

Otitis media with effusion (OME) (also known as secretory otitis media, serous otitis media and ‘glue ear’) is characterised by an accumulation of fluid in the middle ear, in the absence of acute inflammation.Reference Hebda, Piltcher, Swarts, Alper, Zeevi and Doyle1, Reference Butler and van Der Voort2 The condition is the most common cause of acquired hearing loss in children and may negatively affect language development.Reference Butler and van Der Voort2 The aetiology of OME is still uncertain, but low-grade infection, poor eustachian tube function, adenoidal infection or hypertrophy, and pharyngeal reflux have all been implicated.Reference Butler and van Der Voort2–Reference Keles, Ozturk, Gunel, Arbag and Ozer5 In animals and humans, physical obstruction of the eustachian tube or dysfunctional muscle-assisted opening causes OME and can prevent the resolution of otitis media provoked by other causes.Reference Hebda, Piltcher, Swarts, Alper, Zeevi and Doyle1, Reference Bluestone3

Cytokines are glycoproteins produced by macrophages, lymphocytes and other cells. Locally produced, proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6 and IL-8, are considered to play an important role in the initiation and maintenance of inflammation.Reference Hebda, Piltcher, Swarts, Alper, Zeevi and Doyle1, Reference Tada, Furukawa, Ogura, Arai, Adachi and Ikehara6 It has been shown that middle-ear effusions in both animals and humans contain numerous cytokines and inflammatory mediators, including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, histamine, leukotrienes and prostaglandins.Reference Hebda, Piltcher, Swarts, Alper, Zeevi and Doyle1, Reference Yetiser, Satar, Gumusgun, Unal and Ozkaptan4, Reference Tada, Furukawa, Ogura, Arai, Adachi and Ikehara6, Reference McCormick, Saeed, Uchida, Baldwin, Deskin and Lett-Brown7

Conventional medical therapy for OME includes antibiotics, decongestants, antihistamines and combinations of these agents. Decongestants and antihistamines are not effective in resolving effusion.Reference Bluestone3, Reference McCormick, Saeed, Uchida, Baldwin, Deskin and Lett-Brown7, Reference Macknin and Jones8 Some authors offer corticosteroids in the treatment of middle-ear effusion, but there is no consensus on this issue. Various mechanisms have been proposed for the action of corticosteroids: (1) a direct anti-inflammatory action on the middle ear and eustachian tube by reducing arachidonic acid concentration, thereby inhibiting the cyclo-oxygenase and lipo-oxygenase pathways for synthesis of inflammatory mediators; (2) an increase in eustachian tube surfactant concentration, facilitating better tube function; (3) shrinkage of peritubal lymphoid tissue, again allowing better tube function; and (4) reduction of middle-ear fluid viscosity via an effect on mucoproteins.Reference Butler and van Der Voort2, Reference Rosenfeld, Mandel and Bluestone9 Failure of medical treatment of middle-ear effusion frequently results in myringotomy and ventilation tube insertion.Reference Bluestone3, Reference Macknin and Jones8 Although ventilation tubes have a well recognised role in the treatment of OME, their insertion is a surgical procedure and usually requires general anaesthesia in children.

Therefore, the present study investigated the dose-related effectiveness of corticosteroids in the management of OME, using objective measurements.

Materials and methods

This study was carried out in the Selcuk University Medical Research and Application Center and the Department of Biochemistry. It was performed in accordance with the public healthy service (PHS) policy on care and use of laboratory animals, the National Institutes of Health guidance for the care and use of laboratory animals, and the Animal Welfare Act, Turkey. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Selcuk University (number 2004/04).

Forty-two pathogen-free, male, Sprague–Dawley rats weighing between 300 and 350 g (mean 317.4 ± 14.1 g) were selected for the study. The study was designed to have a 90 per cent power in detecting a reduction of 30 per cent between the control and intervention group IL-1β and tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) concentrations.

Subjects were anaesthetised with 50 mg/kg ketamine hydrochloride by intramuscular injection. In all subjects, only the right ear was selected for study, as bilateral surgery has a high mortality rate.Reference Russell and Giles10 All subjects' ears were examined under an operating microscope, and tympanometric evaluations were performed pre-operatively. These were repeated on post-operative days seven, 14 and 30. Subjects with a type A tympanometric pattern, normal tympanic membranes and no infections were included in the study. An impedance audiometer AZ26 system (AZ26, Interacoustics, Assens, Denmark) and were used for tympanometric measurements.

The surgical procedure was as follows. Subjects were placed supine on an operating table. The neck hair was shaved and the skin disinfected with 1 per cent povidone-iodine solution. The surgical procedure described by Russell and GilesReference Russell and Giles10 was performed. An incision approximately 1.5 to 2 cm was made on the skin parallel to the mandibular arch. The superficial fascia, platysma and deep fascia were incised. The latter part of the procedure was performed with the aid of an operating microscope. The dissection was extended more deeply to expose the ventral surface of the right tympanic bulla. The bony part of the eustachian tube was identified. The bone was drilled, and a small piece of gutta percha was placed into the hole (Figure 1). Tissues and skin were sutured primarily. Post-operatively, a single dose of cefazolin (40 mg/kg intramuscularly) was administered for infection prophylaxis.

Fig. 1 Frontal surface of bulla and two-thirds bony segment of the eustachian tube, showing placement of gutta percha in the perforated hole.

Post-operatively, weekly otomicroscopic examination and tympanometric measurements assessed whether an effusion had developed. During otomicroscopy, any retraction, increased vascularisation, tympanic membrane dullness or opalescence, fluid levels, or air bubbles were recorded. Subjects with one or more otomicroscopic signs of OME and a type B tympanogram were considered positive for OME. We excluded from the study the following: three subjects which died due to anaesthetic complications; and three subjects which on the 14th post-operative day showed either no otomicroscopic changes or a non-type-B tympanometric pattern. Therefore, OME was induced in a total of 36 subjects. These 36 subjects were randomly divided into three equal groups, as follows. Group one was the untreated control group. Group two was the low-dose treatment group, receiving 0.5 mg/kg/day intramuscular methylprednisolone for 10 days, beginning from the 20th post-operative day. Group three was the high-dose treatment group, receiving 1 mg/kg/day intramuscular methylprednisolone for 10 days, beginning from the 20th post-operative day. After subjects in group three had been sacrificed, one was noted to have acute mastoiditis (Figure 2); therefore, this subject was excluded, leaving 11 subjects in group three.

Fig. 2 Acute mastoiditis.

On post-operative day 30, subjects were sacrificed via an intramuscular overdose of ketamine hydrochloride. Following sacrifice, the subjects' tympanic bullae were identified by the same surgical procedure. The middles of bullae were drilled. Middle-ear effusions were aspirated with an 18-gauge needle. A 0.1 ml syringe filled with saline was then inserted into the cavity, and the saline injected and then immediately aspirated. The amount of fluid aspirated was supplemented, up to a total volume of 0.5 cm3, with serum saline. Samples were collected for cytokine assay.

IL-1β and TNF-α levels were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Assay kits were used to measure IL-1β and TNF-α concentrations (Biosource International, Camarillo, California, USA). Cytokine levels were measured and expressed as a mean (in pg/ml).

Results were given as mean ± standard deviation. Variance analysis was conducted in two-way repeated measurements. In case of significant results, one-way variance analysis with a Bonferroni correction was carried out to determine the difference between groups. The Tukey-HSD test was used as the post hoc test of this variance analysis. A paired t-test with a Bonferroni correction was employed in comparisons within each group. A result of p < 0.05 was accepted as significant, while p < 0.01 was considered as significant in comparisons with a Bonferroni correction.

Results

Three of the 42 subjects died on the first post-operative day due to anaesthetic complications. Tympanometric measurements carried out on the 14th post-operative day showed that 36 subjects (92.3 per cent) had signs compatible with OME. Three subjects were found to be normal on otomicroscopic examination and were thus excluded from the study. When an autopsy was conducted on these subjects, the gutta percha, inserted to obstruct the eustachian tube, was found to be displaced.

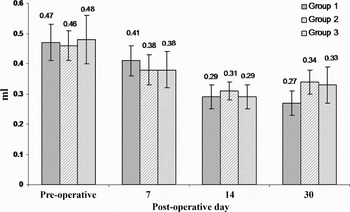

The subjects included in the study weighed between 300 and 350 g; the weight distributions of the groups were similar (p > 0.05). Figures 3 and 4 show, respectively, the values for middle-ear pressures and compliances, according to group and post-operative day. Otomicroscopic examination conducted on the seventh post-operative day revealed subjects' tympanic membranes to be slightly retracted and hypervascularised. Tympanometric examination showed that all three tympanometric patterns were present; however, the most common was type C. Otomicroscopic examination repeated on the 14th post-operative day showed dullness, retraction and hypervascularity of the tympanic membrane and an air–fluid level or air bubbles behind the tympanic membrane. In the control group, results for otomicroscopy and tympanometry on the 30th post-operative day were similar to those on the 14th post-operative day (p > 0.05). Results for otomicroscopy and tympanometry in the low-dose and high-dose corticosteroid groups were similar (p > 0.05), but subjects' OME was observed to have recovered, comparing findings on the 14th and 30th post-operative days (Figures 3 and 4). While a type B tympanometric pattern was obtained in the control group, a type C tympanometric pattern was found in most subjects in the low-dose and high-dose corticosteroid groups. There were no significant differences between the low-dose and high-dose corticosteroid groups with regards to pressure and compliance results (p > 0.05, p > 0.05, respectively). On the other hand, statistically significant differences were observed between the pressure and compliance results of the control group and those of the low-dose corticosteroid group (p < 0.01), as well as between these same results of the control group and those of the high-dose corticosteroid group (p < 0.01). In the control group, the differences between the pressure and compliance results observed on the 14th and 30th post-operative days were not statistically significant (p > 0.05, p > 0.05, respectively). In the two intervention groups, the observed differences in the tympanometric measurements between the pre-operative and 30th post-operative days, and between the 14th and 30th post-operative days, were statistically significant (p < 0.01, p < 0.01, respectively).

Fig. 3 Middle-ear pressures for the three groups over time.

Fig. 4 Compliance values for the three groups over time.

When bullae were drilled, all those from the control group (100 per cent) were found to contain fluid. Of these effusions, nine (75 per cent) were mucoid (Figure 5) and three (25 per cent) were serous (Figure 6). In the low-dose corticosteroid group, five subjects (41.7 per cent) were observed to have serous fluid, while seven (58.3 per cent) did not have any fluid (Figure 7). In the high-dose steroid group, three subjects (27.3 per cent) had serous fluid, whereas eight (72.7 per cent) had no fluid. None of subjects in the low-dose or high-dose corticosteroid groups had mucoid effusions.

Fig. 5 Presence of mucoid fluid.

Fig. 6 Presence of serous fluid.

Fig. 7 Absence of fluid (but oedematous middle-ear mucosa).

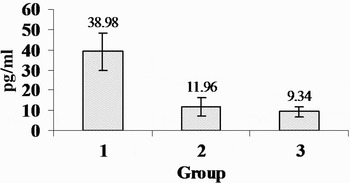

The observed IL-1β and TNF-α levels are shown in Figures 8 and 9, respectively. Concentrations of both IL-1β and TNF-α were significantly higher in the control group than in the low- and high-dose corticosteroid groups (p < 0.01, p < 0.01, respectively). However, there was not a significant difference in this respect between the low-dose and the high-dose corticosteroid groups (p > 0.05).

Fig. 8 Distribution of interleukin-1β concentrations for the three groups.

Fig. 9 Distribution of tumour necrosis factor α concentrations for the three groups.

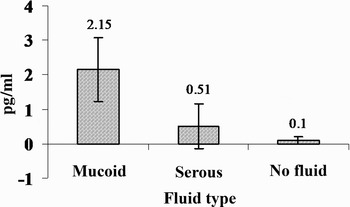

The relationship between OME fluid characteristics and IL-1β and TNF-α concentrations is shown in Figures 10 and 11. The relationships between fluid characteristics and IL-1β and TNF-α concentrations were significant (p < 0.01, p < 0.01, respectively).

Fig. 10 Relationship between interleukin-1β concentration and otitis media fluid characteristics.

Fig. 11 Relationship between tumour necrosis factor α concentration and otitis media fluid characteristics.

Discussion

Otitis media with effusion is defined as chronic inflammation of the middle-ear mucosa. It is a common reason for prescribing antibiotics, contributing to the growing problem of bacterial resistance.Reference Butler and van Der Voort2 The mechanism of OME is not clearly understood. Obstruction of the eustachian tube is known to be the main and basic mechanism of OME. However, additional mechanisms are proposed to play a role in producing effusion.Reference Hebda, Piltcher, Swarts, Alper, Zeevi and Doyle1, Reference Bluestone3

Inflammatory mediators such as leukotrienes, prostaglandins, platelet-activating factor, histamine, enzymes, antibodies and other agents have been identified in middle-ear effusions.Reference Hebda, Piltcher, Swarts, Alper, Zeevi and Doyle1, Reference Yetiser, Satar, Gumusgun, Unal and Ozkaptan4, Reference Tada, Furukawa, Ogura, Arai, Adachi and Ikehara6, Reference McCormick, Saeed, Uchida, Baldwin, Deskin and Lett-Brown7 Cytokines are basically glycoproteins, which are known to be released from inflammatory cells as well as epithelial cells stimulated by various mediators; they play a regulatory role in both inflammation and the immune system.Reference Yetiser, Satar, Gumusgun, Unal and Ozkaptan4, Reference Tada, Furukawa, Ogura, Arai, Adachi and Ikehara6, Reference McCormick, Saeed, Uchida, Baldwin, Deskin and Lett-Brown7

Recent studies have demonstrated the presence of a variety of cytokines in middle-ear effusions. Therefore, we investigated the concentrations of TNF-α and IL-1β in middle-ear effusions. Previously, IL-1β and TNF-α concentrations have been found to be significantly higher in mucoid effusions than in serous effusions.Reference Yetiser, Satar, Gumusgun, Unal and Ozkaptan4 Our results were similar. The highest IL-1β and TNF-α levels were found in mucoid fluid, whereas the lowest levels were found in the absence of middle-ear fluid. Concentrations of IL-1β and TNF-α were significantly lower in subjects without middle-ear-effusion, compared with those with mucoid and serous effusions.

Although ventilation tube insertion has a well recognised role in the treatment of OME, the procedure usually needs to be performed under general anaesthesia in children.Reference Bluestone3, Reference Macknin and Jones8, Reference Lambert11 Furthermore, the procedure may cause complications, such as tympanic membrane perforation, aural discharge, sclerotic changes in the tympanic membrane, hearing loss and cholesteatoma.Reference Lambert11, Reference Berman, Casselbrant, Chonmaitree, Giebink, Grote and Ingvarsson12 Therefore, the search continues for an effective medical treatment for OME.

In the conservative treatment of OME, the role of corticosteroids is controversial. Macknin and JonesReference Macknin and Jones8 found no difference between dexamethasone and placebo in clearing middle-ear effusions or improving hearing in children with middle-ear effusions. LambertReference Lambert11 found that the combination of prednisone and amoxicillin was no more effective than amoxicillin plus placebo in resolving persistent middle-ear effusion. Butler et al. Reference Butler and van Der Voort2 found no evidence for lasting benefit from oral or topical nasal steroid treatment of OME.

On the other hand, Podoshin et al.,Reference Podoshin, Fradis, Ben-David and Faraggi13 in a double-blind, randomised study, showed that a group treated with amoxicillin and steroids had a much better response than groups treated with placebo or amoxicillin alone. Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Puglese and Schwartz14 reported that results for 40 children treated with steroids either initially or following crossover revealed that 70% demonstrated resolution of OME via pneumo-otoscopy and 64% via tympanometry. Persico et al. Reference Persico, Podoshin and Fradis15 found that 53 per cent of children treated with a combination of prednisone and ampicillin achieved resolution of OME; after two weeks of treatment, twice as many ears were cleared by dexamethasone treatment compared with placebo.

In the present study, a significant difference was observed for concentrations of both IL-1β and TNF-α between both intervention groups and the control group. However, there was no significant difference in this respect between the low- and high-dose corticosteroid groups.

In the control group, examination of middle-ear fluid characteristics showed that nine subjects had mucoid effusions and three had serous effusions. In the low-dose corticosteroid group, five subjects had serous effusions whereas seven had no effusion. In the high-dose corticosteroid group, three subjects had serous effusions and eight had no effusion. All subjects in the control group had a middle-ear effusion, either mucoid or serous, while no subject receiving corticosteroid treatment had a mucoid effusion.

• This study examined the dose-related effectiveness of corticosteroids in the management of otitis media with effusion in an experimental model

• Corticosteroids made a significant difference in resolving the effusion, when compared with a control group

• Only short term outcomes were assessed in this study, and further studies are needed to ascertain the optimal dose and duration of such treatment

Similarly, following OME formation, tympanometric examinations revealed an improvement in the groups administered corticosteroid treatment, but no such improvement in the control group.

In both groups receiving corticosteroid treatment, the middle-ear fluid and the concentrations of IL-1β and TNF-α were suppressed. In these groups, tympanometry values and otomicroscopic examination findings on the 30th post-operative day were similar to those obtained on the 7th post-operative day, but not as good as those obtained pre-operatively. Since obstruction of the eustachian tube was permanent in our experiment, improvement may have been limited. We found the effects of low-dose and high-dose corticosteroid on middle-ear effusion to be similar. Thus, our results support the theory that a 0.5 mg/kg corticosteroid dose is as effective as a 1 mg/kg corticosteroid dose in an experimental model of OME. A low-dose regime may help decrease adverse reaction to corticosteroids.

Acknowledgement

This study was sponsored by a contract grant from the Selcuk University Research Foundation (grant number 2004/04). We thank Dr Tahir Kemal Sahin for statistical analysis.