Introduction

Bell's palsy is peripheral facial palsy of unknown cause. It is relatively common, with an estimated incidence of 13–34 cases per 100 000.Reference Peitersen 1 , Reference Hauser, Karnes, Annis and Kurland 2

Patients with Bell's palsy typically present with a unilateral facial paresis which develops within hours. Examination shows eyebrow sagging, inability to close one eye, disappearance of one of the nasolabial folds, and mouth asymmetry. The onset is generally acute, with maximum facial palsy within three or four days. In 85 per cent of patients, facial nerve function returns within three weeks.Reference Peitersen 3 Recurrence rates of 7–11 per cent have been reported.Reference Pitts, Adour and Hilsinger 4 – Reference van Amstel and Devriese 7

Simultaneous, bilateral facial palsy is much rarer than unilateral palsy, with an incidence of 0.3–2 per cent.Reference Sherwen 8

When a peripheral facial palsy recurs or affects both sides of the face, an idiopathic cause is less likely.

We present two cases of recurrent and (at times) bilateral facial palsy, and we summarise the differential diagnoses of a recurrent or bilateral peripheral facial palsy.

To prepare this summary, we searched PubMed for ‘Bell's palsy’, ‘peripheral’ OR ‘bilateral’ OR ‘recurrent’ AND (‘facial palsy’ OR ‘facial palsy’, ‘facial paresis’).

Case reports

Case one

A 76-year-old woman suddenly developed a left facial palsy, with inability to close her left eye firmly, asymmetry of the mouth and disappearance of the nasolabial fold. Her medical history included hypothyroidism, for which she took levothyroxine 0.05 mg daily. The patient's mother had previously suffered Bell's palsy.

We diagnosed Bell's palsy and prescribed the patient prednisone 25 mg twice daily for 10 consecutive days.Reference Salinas, Alvarez, Daly and Ferreira 9

However, two months later she returned to our out-patient clinic because of deterioration of the Bell's palsy: her facial palsy was now complete and she could not move her left facial musculature.

Blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination results (including angiotensin-converting enzyme and lysozyme testing) were normal. Tests for Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi in both serum and CSF were negative, as was viral polymerase chain reaction testing of the CSF. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed several white matter lesions but gave no explanation for the facial palsy. A chest X-ray was normal.

A few weeks later, the patient could close her left eye again and use her mouth adequately, but a mild paresis was still seen.

Less than three months later, she returned to our out-patient clinic because of salvia loss from the right corner of her mouth. Examination identified loss of the right nasolabial fold without evident weakness of the upper facial muscles. Another MRI scan was performed due to suspicion of a central facial paresis, but this scan was identical to the previous one suggesting a partial peripheral facial palsy. Blood and CSF examinations were again normal.

Thus, despite extensive additional investigation, we could find no underlying cause of this patient's alternating, recurrent facial palsy, other than a possible familial susceptibility.

Case two

The second patient was a 44-year-old man who had previously suffered a left-sided Bell's palsy at the age of 35 years, with complete recovery. He visited our out-patient clinic with a four-week history of right-sided peripheral facial palsy, which had been preceded by an upper airway infection. Recently, he had been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and hypertension, and had started a diet to control his diabetes.

A brain MRI scan showed hyper-intensity of the labyrinthine segment of the right facial nerve and of the right geniculate ganglion, typical of Bell's palsy. A chest X-ray was normal.

Three weeks later, the patient also developed a left facial palsy, with no other neurological deficits.

At this stage, blood examination demonstrated an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (29 mm/hour) and a slightly elevated γ globulin test (59 U/l), without any other abnormalities (the angiotensin-converting enzyme concentration was normal). The CSF had a high protein content (839 mg/l) and a slightly elevated glucose concentration (3.9 mmol/l), with a normal number of leukocytes. Microscopic examination of the CSF showed a cell-rich liquor with many lymphocytes and some monocytes. However, viral polymerase chain reaction and T pallidum and B burgdorferi testing of both CSF and serum were all negative.

Four months later, the patient's left-sided Bell's palsy was observed to have almost completely recovered. On the right side, there was some improvement: he could close his right eye again, but there was still diminished blinking and marginal movement of the mouth.

The underlying cause of this patient's bilateral facial palsy was never found, although diabetes mellitus and hypertension were identified as risk factors.

Discussion

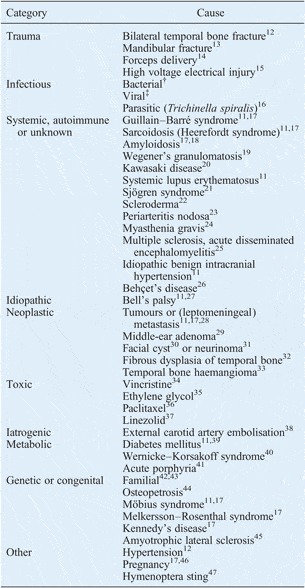

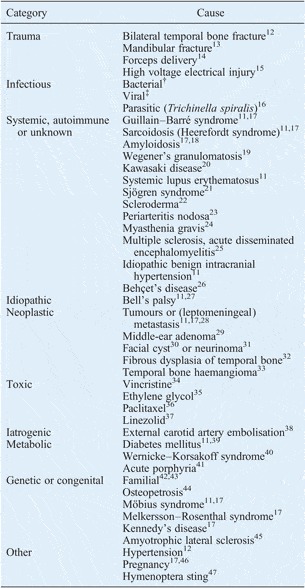

The two patients described above illustrate the difficulty of identifying an underlying cause for recurrent and bilateral facial palsies. An idiopathic aetiology is still possible: Navarrette et al. Reference Navarrete, Cespedes, Mesa, Grasa, Perez and Raguer 10 reported that 84 per cent (77/92) of their recurrent facial palsy cases remained idiopathic, while KeaneReference Keane 11 reported that 23 per cent (10/43) of their bilateral facial palsy cases remained idiopathic. However, efforts should be undertaken to identify a (treatable) cause in each patient with recurrent or bilateral peripheral facial palsy. Table I shows the differential diagnosis of recurrent or bilateral facial palsy.

Table I Causes of recurrent or bilateral peripheral facial paresis

Note that muscle disorders and causes located in the central nervous system (e.g. pontine haemorrhage or infarction)Reference Keane 11 , Reference Roh, Kim and Chung 48 can mimic bilateral peripheral facial palsy. † Borrelia burgdorferi,Reference Ropper and Samuels 17 Treponema pallidum,Reference Keane 11 , Reference Ropper and Samuels 17 , Reference Strauss 49 Mycobacterium tuberculosis,Reference Keane 11 Mycobacterium leprae,Reference Keane 11 Mycoplasma pneumoniae,Reference Ernster 50 Leptospira interrogans,Reference Silva, Ducroquet and Pedrozo 51 Clostridium tetani Reference Brown 52 and bacterial otitis caused by other bacteria.Reference Keane 11 , Reference Menassa, Sawaya, Masri and Arayssi 26 ‡Epstein– Barré virus,Reference Ropper and Samuels 17 , Reference Ramsey and Kaseff 28 herpes simplex virus,Reference Santos and Adour 53 human immunodeficiency virus,Reference Keane 11 , Reference Ropper and Samuels 17 varicella zoster virus,Reference Ramsey and Kaseff 28 rubella virusReference Jamal and Al-Husaini 54 and poliovirus.Reference Sherman and Kimelblot 55

As shown in Table I, there are several viral and bacterial agents which can cause a bilateral or recurrent facial palsy. It is hypothesised that Bell's palsy is caused by infection with herpes simplex virus (HSV). The best proof of this is given by Murakami et al.,Reference Murakami, Mizobuchi, Nakashiro, Doi, Hato and Yanagihara 56 who found HSV DNA in the endoneural fluid surrounding the facial nerve, obtained during surgical decompression in patients with Bell's palsy. Endoneural fluid cannot be obtained routinely, but we did screen both our patients for several viral agents (including HSV in the CSF) and also for T pallidum and B burgdorferi in both serum and CSF. However, in both patients all such tests were negative.

Guillain–Barré syndrome is an important post-infectious cause of facial palsy. However, patients with this syndrome typically present with bilateral facial palsy after an infection, generally accompanied by weakness of the extremities and absence of tendon reflexes.

Another post-infectious cause of bilateral facial palsy is malaria infection, although we found only one report of this.Reference Kochar, Sirohi, Kochar, Bindal, Kochar and Jhajharia 57

In the Introduction, we describe the typical course of Bell's palsy. An atypical course, as seen in our first patient, could indicate a less another cause. This patient's facial palsy was slowly progressive, which raises suspicion of a tumour. In addition, the involvement of only one of the distal branches of the facial nerve suggested local compression.Reference Boahene, Olsen, Driscoll, Lewis and McDonald 58 – Reference May and Hughes 61 However, the brain MRI did not show any signs of tumour or leptomeningeal metastasis. In case two, an MRI scan was performed three weeks before development of bilateral facial palsy. This MRI demonstrated enhancement of the labyrinthine segment of the facial nerve, typical of Bell's palsy.Reference Schwaber, Larson, Zealear and Creasy 62

-

• Recurrent or bilateral facial palsy has an extensive differential diagnosis

-

• Searching for causes reduces the number of idiopathic (Bell's palsy) diagnoses

-

• No cause is found for 84 per cent of recurrent facial palsy cases

-

• No cause is found for 23 per cent of bilateral facial palsy cases

A notable aspect of case one was the presence of a positive family history of Bell's palsy. Previous reports have mentioned the possibility of genetic susceptibility, which has been demonstrated in 2.4–28.6 per cent of cases.Reference Auerbach, Depiero and Mejlszenkier 63 However, no consistent pattern of inheritance has been found.Reference Clement and White 42 , Reference Qin, Ouyang and Luo 64 Human leukocyte antigens were hypothesised to be involved; however, studies have shown ambiguous results.Reference Döner and Kutluhan 43 , Reference Smith, Hammarström and Sidén 65 – Reference Savadi-Oskouei, Abedi and Sadeghi-Bazargani 68 Cawthorne and HaynesReference Cawthorne and Haynes 5 suggested that this familial tendency was due to extremely cellular mastoids; they noted that all patients with recurrent Bell's palsy had extensive, cellular mastoids.

Diabetes mellitus and hypertension have been mentioned as risk factors for Bell's palsy, and were also found in our second case.Reference Savadi-Oskouei, Abedi and Sadeghi-Bazargani 68 Pitts et al. Reference Pitts, Adour and Hilsinger 4 have stated that patients with recurrent facial palsy are 2.5 times more likely to have diabetes, probably because diabetic patients are more prone to nerve degeneration. Hypertension also increases the risk, but the association is less strong. It is hypothesised that hypertension causes facial paresis through direct pressure from a dilated vessel, oedema or haemorrhage within the facial canal.Reference Harms, Rotteveel, Kar and Gabreëls 69

Conclusion

When a patient has a recurrent or bilateral facial palsy, diagnoses other than Bell's palsy should be considered. In addition to extensive anamnestic data collection, investigation should include blood examinations and contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain. If the diagnosis still remains unclear after such investigation, a chest X-ray should be performed to search for systemic disease, and the CSF should be examined to diagnose infection and exclude leptomeningeal metastasis. Anamnestic data may prompt further investigation.

Unfortunately however, no specific cause can be found for a large number of recurrent or bilateral facial palsy cases, as exemplified by our presented patients.Reference Navarrete, Cespedes, Mesa, Grasa, Perez and Raguer 10 , Reference Keane 11 In the future, expanding clinical knowledge and diagnostic possibilities may enable the identification of a specific cause in more of these patients.