Introduction

Anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane are technically difficult to repair because of insufficient visualisation, decreased graft viability due to poor vascularisation, inadequate anterior membrane remnant and poor stabilisation.Reference Eren, Tugrul, Ozucer, Veyseller, Aksoy and Ozturan1 Various surgical techniques (underlay, overlay, interlay, loop-overlay, hammock, window-shade, push-through and butterfly inlay) and graft materials (fascia, perichondrium and cartilage) for repairing anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane have been described.Reference Eren, Tugrul, Ozucer, Veyseller, Aksoy and Ozturan1–Reference Celik, Samim and Oztuna4 Although all of the aforementioned tympanoplasty techniques are effective in the treatment of anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane, other techniques, except for butterfly-inlay and push-through techniques, require tympanomeatal flap elevation, retroauricular or endaural skin incision, anterior canalplasty, and relatively advanced surgical skills.

The postauricular approach gives the best view of anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane, especially the anterior margin of the perforation. Nonetheless, in patients with anterior canal wall protrusion, anterior canalplasty may be necessary to entirely expose anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane even in conventional microscopic postauricular approaches.Reference Eren, Tugrul, Ozucer, Veyseller, Aksoy and Ozturan1,Reference Jako5 The endoscope bypasses the narrowest portion of the external auditory canal, allowing the surgeon to view the concealed areas in the middle ear and especially the anterior margin of anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane without anterior canalplasty.Reference Jako5 Therefore, endoscopic transcanal approaches avoid anterior canalplasty and periauricular skin incision, which may result in increased post-operative morbidity.Reference Tarabichi, Nogueira, Marchioni, Presutti, Pothier and Ayache6

The butterfly-inlay cartilage tympanoplasty technique, first described by Eavey, does not require any surgical incisions other than the incision for graft harvesting.Reference Eavey7 In this technique, sponge buffer, which is used for graft support and may cause a feeling of fullness in the ear, is not placed, offering increased post-operative patient satisfaction and shorter operative time. There have recently been noteworthy studies related to minimally invasive push-through tympanoplasty with comparable surgical and functional results in the treatment of anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane.Reference Celik, Samim and Oztuna4,Reference El-Hennawi, Ahmed, Abou-Halawa and Al-Hamtary8 However, to the best of our knowledge, there is currently no study directly comparing the outcomes of these two minimally invasive techniques for repairing anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane.

This study aims to compare the surgical and functional results of endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty and endoscopic push-through myringoplasty in repairing anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

A total of 71 patients who underwent endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty (n = 34) or endoscopic push-through myringoplasty (n = 37) for anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane in the otorhinolaryngology clinics of a tertiary private hospital between January 2015 and September 2018 were included in this open-label randomised clinical study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study received approval from the local ethics committee. Prior to surgery, participants were randomly divided into two groups to be operated on with either endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty or endoscopic push-through myringoplasty.

Patients without active middle-ear infection at least three months prior to surgery, without conductive hearing loss suggesting ossicular chain damage (less than 30 dB) and only patients with perforation localised to the anterior quadrant (both anteroinferior and anterosuperior quadrants) of the tympanic membrane that did not exceed past the line extending along the manubrium mallei were included in the study. All patients who were included in the study were operated on under hypotensive general anaesthesia by the same surgeon.

Patients with histories of chronic otitis surgery, mixed-type hearing loss, mastoidectomy due to cholesteatoma, perforation not localised in the anterior quadrant and patients without post-operative follow up were excluded from the study. Patients with marginal perforations without adequate tympanic membrane remnants in the anterior boundary, who are not suitable for endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty and endoscopic push-through myringoplasty techniques, were also excluded from the study.

Parameters investigated

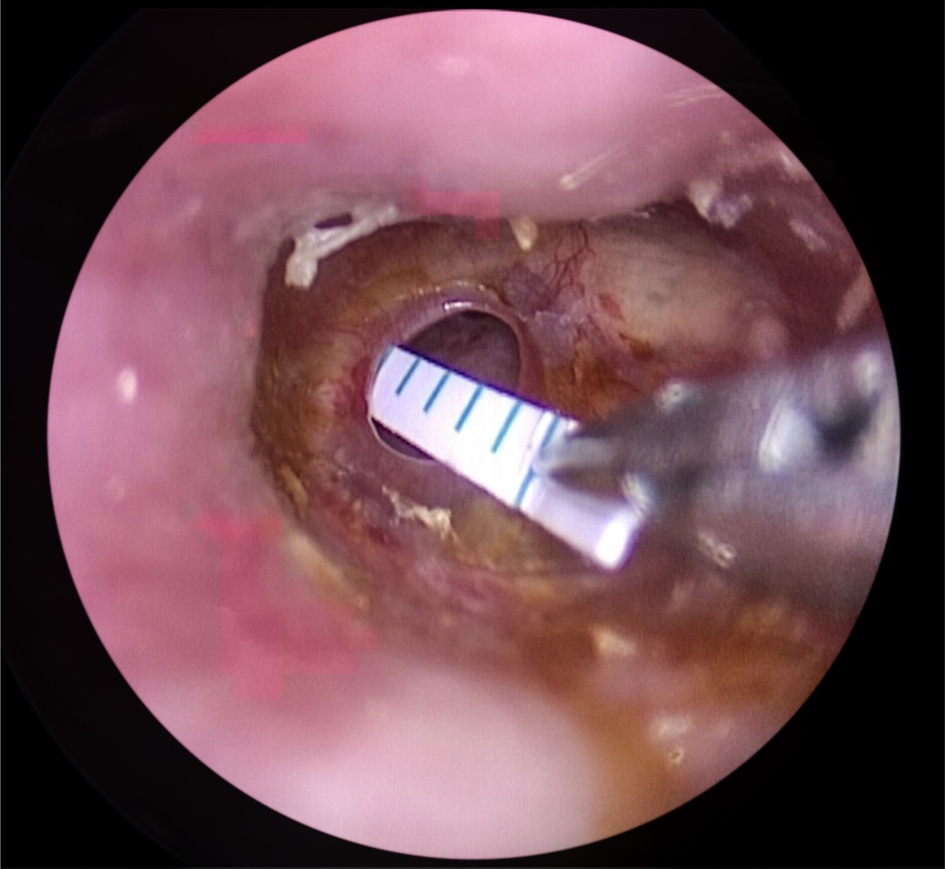

Graft success rates, hearing outcomes, operative times and complications in patients with anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane who underwent endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty or endoscopic push-through myringoplasty were compared. After at least a six-month post-operative follow-up period, patients with an intact tympanic membrane, as seen in an endoscopic examination, were considered to have successful graft uptake, while patients with graft reperforation or medialisation were considered to have unsuccessful graft uptake. The perforation diameter of the tympanic membrane of all patients in both groups was precisely measured intra-operatively with the help of an alligator forceps using a disposable paper ruler as shown in Figure 1, and the effect of perforation diameter on graft success was investigated.

Fig. 1. Precise measurement of the perforation diameter using a disposable paper ruler.

Mean air-conduction thresholds, mean bone-conduction thresholds and mean air–bone gap (ABG) values were calculated according to pre-operative and six-month post-operative pure tone audiometry and compared. Mean ABG closure (pre-operative mean ABG value minus post-operative mean ABG value) was also compared between the groups. Mean value of pre-operative and post-operative pure tone audiometry measurements taken at four frequencies (0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz) were calculated and assessed according to the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Committee on hearing and equilibrium guideline recommendations.

The total time from the beginning to the end of surgery was taken into consideration when calculating the mean operative time. This study also investigated whether anterior canal wall protrusion had any effect on mean operative time in patients with anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane who underwent endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty or endoscopic push-through myringoplasty. Patients in which the anterior margin of the perforation could not be fully viewed in the otoscopic examination due to anterior wall protrusion of the external ear canal were considered to be patients with anterior canal wall protrusion. All intra-operative and post-operative complications were documented.

Surgical technique

Endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty and endoscopic push-through myringoplasty procedures were performed using a 0-degree rigid endoscope that was 4 mm in diameter and 18 cm long. Perforation diameters were accurately measured in both surgical techniques with the aid of an alligator forceps using a disposable paper ruler (Figure 1).

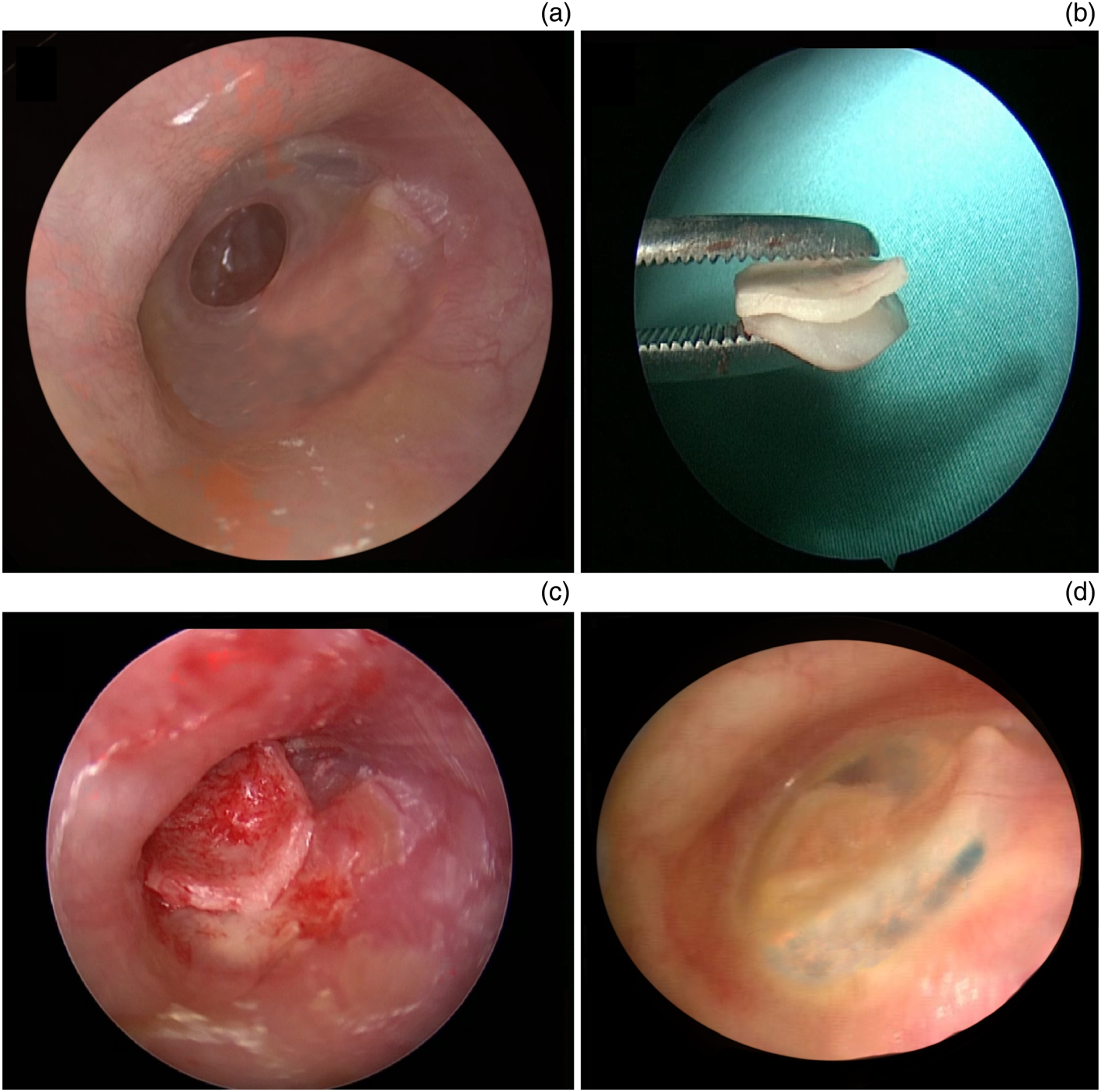

Chondroperichondrial composite graft, harvested from the tragus while preserving the lateral perichondrium layer, was used for perforation repair in both groups. In the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty group, after desepitalisation of the perforation margins, chondroperichondrial composite graft was shaped to be 1–2 mm wider than the diameter of the perforation. After shaping, a 1-mm deep circular incision was made around the entire margin of the chondroperichondrial composite graft using a number 12 lancet for the butterfly-inlay technique. The perichondrium layer of the chondroperichondrial composite graft prepared for the butterfly-inlay technique was endoscopically placed to be lateral to the tympanic membrane and was then checked to make sure it was placed properly with the aid of a curved needle (Figure 2). An absorbable sponge tampon was not placed in either the middle ear or external ear canal to support the graft in the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty group, but an antibiotic pomade containing bacitracin and neomycin (Thiocilline, Abdi Ibrahim, Istanbul, Turkey) was spread on the graft in a thin layer with the help of a Rosen elevator.

Fig. 2. Images showing the steps of endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty: (a) an intra-operative view of the anterior tympanic membrane perforation; (b) chondroperichondrium composite graft preparation for a butterfly-inlay grafting; (c) an intra-operative view of the perforation after endoscopic butterfly-inlay grafting; and (d) an appearance of the completely healed graft at six months post-operatively.

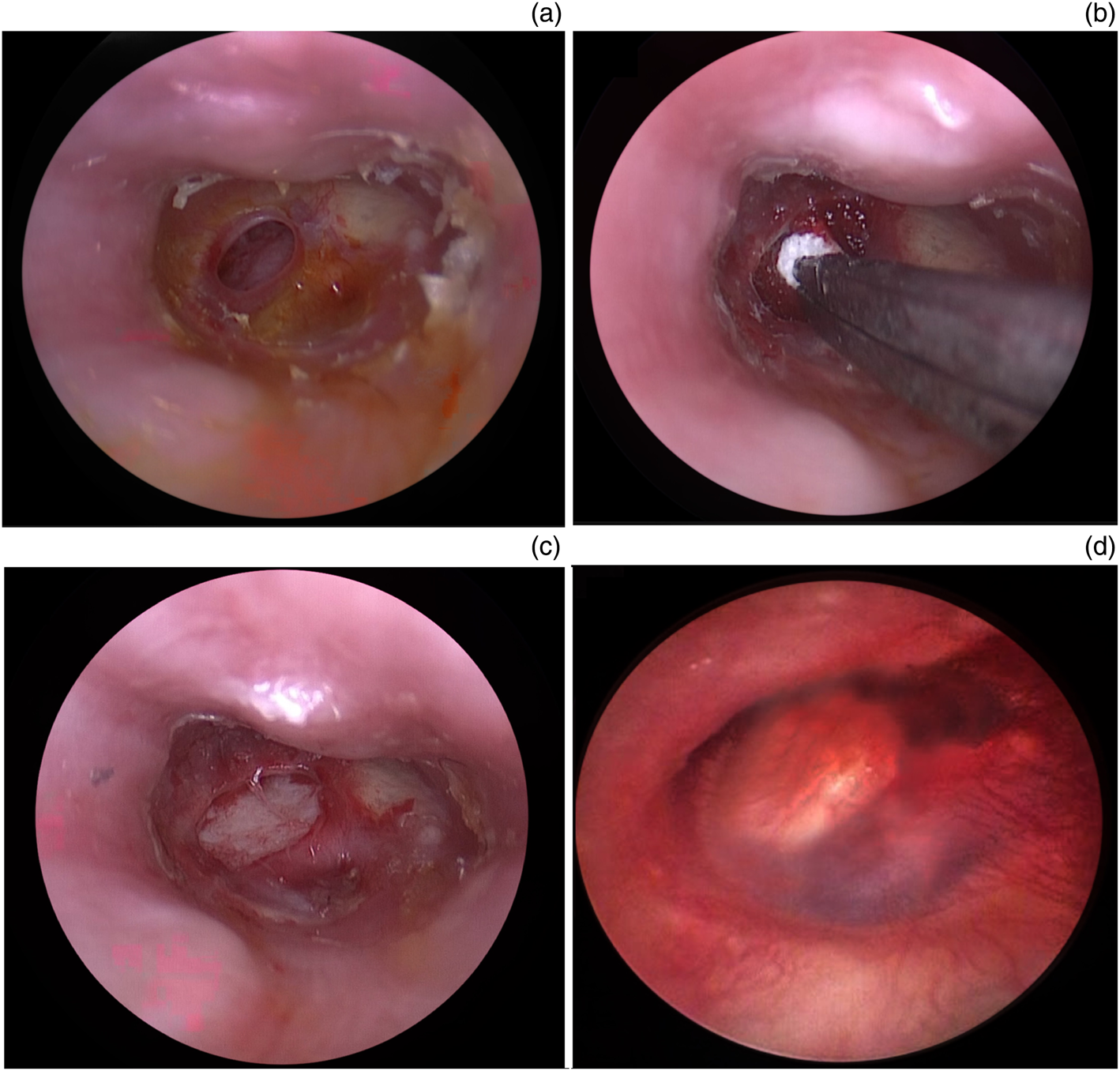

In patients who underwent endoscopic push-through myringoplasty, after perforation edges were renewed, the middle ear and especially the Eustachian tube orifice were tightly packed with Gelfoam® to prevent graft medialisation. The chondroperichondrial composite graft, shaped to be approximately 1–2 mm wider than the perforation diameter, was pushed through the perforation and the perichondrium layer was placed facing outwards (Figure 3). The external ear canal was filled to the isthmus level with Gelfoam.

Fig. 3. Steps of the endoscopic push-through myringoplasty: (a) an endoscopic appearance of the anterior tympanic membrane perforation; (b) packing the middle ear to prevent graft medialisation; (c) an appearance of the endoscopically placed chondroperichondrium composite graft using the push-through technique; and (d) a view of the healed tympanic membrane at six months post-operatively.

The graft incision in the medial surface of the tragus was closed with absorbable suture after grafting in both groups, and a cotton tampon mixed with Thiocilline pomade was tightly placed in the inlet of the external ear canal to prevent haematoma. Finally, the auricle was closed with a small gauze dressing in both groups.

Post-operative period

Patients were prescribed oral amoxicillin-clavulanate antibiotics at discharge to use for one week and paracetamol for pain as needed. Patients of both groups were called for a check-up one week after the operation to remove the wound dressing. Eardrops containing ciprofloxacin were administered to all patients in addition to oral antibiotics to use for one additional week. Our standard follow-up policy after endoscopic transcanal tympanoplasty consists of routine control examinations at the first week, second week, first month, third month and sixth month, post-operatively. In the sixth month post-operatively, otoscopic examination and pure tone audiometry were performed for all patients allowing evaluation of graft success rates and hearing outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS® (version 22) statistical software for Windows 10®. The normality of data was checked using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the appropriate test was chosen. Categorical variables between groups were compared using the Pearson chi-square test. The student's t-test was used for analysing data with normal distribution, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for data without normal distribution. Results were presented as mean, median and percentage. A p-value with a 95 per cent confidence interval less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 71 patients with anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane who underwent type-1 tympanoplasty with endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty (n = 34) or endoscopic push-through myringoplasty (n = 37) techniques were included in the study.

Of the patients in the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty group, 15 (44.1 per cent) were female, 19 (55.9 per cent) were male, and 12 (35.2 per cent) right ears and 22 (64.8 per cent) left ears were operated on. The average age of the patients in the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty group was 31.6 ± 10.8 years (range, 21–47 years).

There were 16 (43.3 per cent) females and 21 (56.7 per cent) males in the endoscopic push-through myringoplasty group, and 17 (45.9 per cent) right ears and 20 (54.1 per cent) left ears were operated on. The mean age of patients in the endoscopic push-through myringoplasty group was 29.6 ± 7.8 years (range, 23–45 years).

The mean perforation diameters of patients were 4.9 ± 1.7 mm (range, 3–5.5 mm) and 4.7 ± 1.1 mm (range, 2.5–5 mm) for the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty and endoscopic push-through myringoplasty groups, respectively (p > 0.05). The mean post-operative follow-up time for endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty and endoscopic push-through myringoplasty groups was 8.2 and 11.6 months, respectively.

According to the otoendoscopy performed at the end of the six-month post-operative follow up, graft success rates in the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty and endoscopic push-through myringoplasty groups were 94.1 per cent (32 out of 34 patients) and 91.8 per cent (34 out of 37 patients), respectively (p > 0.05). The reason for graft failure in the two patients in the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty group was graft reperforation. In the endoscopic push-through myringoplasty group, graft failure occurred in three patients due to medialisation (n = 2) and reperforation (n = 1). Furthermore, there was no significant correlation between perforation diameter (up to 5.5 mm and 5 mm in endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty and endoscopic push-through myringoplasty groups, respectively) and graft success rates in either the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty group (p = 0.685) or the endoscopic push-through myringoplasty group (p = 0.894).

According to pre-operative and six-month post-operative pure tone audiometry measurements, a significant improvement in post-operative ABG values was observed in both groups, whereas there was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.917) between groups in terms of ABG closure (Table 1). Pre-operative mean (± standard deviation (SD)) ABG values of 16.8 ± 3.7 dB improved to 5.2 ± 4.1 dB post-operatively in the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty group (p < 0.001). Pre- and post-operative mean (± SD) ABG values of the patients who underwent endoscopic push-through myringoplasty were 18.2 ± 5.1 dB and 6.1 ± 3.6 dB, respectively (p < 0.001).

Table 1. Comparison of pre- and post-operative ABG values and ABG closure in both groups

*A p-value less than 0.05, calculated with a 95 per cent confidence interval, was considered to be statistically significant. ABG = air–bone gap; EBICM = endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty; EPTM = endoscopic push-through myringoplasty; SD = standard deviation

There were 9 (26.4 per cent) anterior canal wall protrusion patients in the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty group and 11 (29.7 per cent) in the endoscopic push-through myringoplasty group (p > 0.05). None of the patients in either group required anterior canalplasty due to anterior canal wall protrusion. The average operative time was significantly shorter in the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty group compared with the endoscopic push-through myringoplasty group (Table 2). Furthermore, when the groups were compared separately, anterior canal wall protrusion did not seem to significantly extend operative time in either the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty (p = 0.124) or endoscopic push-through myringoplasty (p = 0.347) group (Table 3).

Table 2. Comparison of operative times between groups

*A p-value less than 0.05, calculated with a 95 per cent confidence interval, was considered to be statistically significant. EBICM = endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty; EPTM = endoscopic push-through myringoplasty; SD = standard deviation

Table 3. Comparison of operative times between patients with and without anterior canal wall protrusion in both groups

*A p-value less than 0.05, calculated with a 95 per cent confidence interval, was considered to be statistically significant. ACWP = anterior canal wall protrusion; SD = standard deviation; EBICM = endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty; EPTM = endoscopic push-through myringoplasty

Post-operative myringitis was observed in three patients (8.8 per cent) in the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty group, and despite oral and topical antibiotic treatments, graft reperforation occurred in two of those patients. The iatrogenic tear of the tympanic membrane leading to an enlargement of the perforation occurred in 4 patients (10.8 per cent) during the graft placement in the endoscopic push-through myringoplasty group, and 2 of those patients developed graft medialisation.

Discussion

In the last quarter of the twentieth century, endoscopes began to be employed as the primary or assistant device in ear examination and chronic otitis media surgery; thus, the endoscopy era in otology started. Utilisation of endoscopes in ear surgery has brought significant advantages, such as visualising concealed areas without bony curettage, ensuring significantly shorter operative times compared with microscopic approaches and providing minimally invasive surgery with fewer complications.Reference Özgür, Dursun, Erdıvanlı, Coskun, Terzı and Emıroglu9

The inability to view the anterior margin of anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane because of a prominent anterior canal wall makes myringoplasty difficult when operating with the surgical microscope. In such circumstances, anterior canalplasty, associated with increased operative time and post-operative morbidity, is required to visualise anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane completely.Reference Celik, Samim and Oztuna4 Additionally, the endoscopic approach, which makes the surgical procedure more easily understandable, is better for educational and training purposes because it provides a wide-angle view and excellent magnification without resolution loss.Reference Iannella and Magliulo10 Despite these substantial advantages, the lack of a stereoscopic view, single-handed surgery and a prolonged learning curve are the main limitations of endoscopic transcanal ear surgical procedures.Reference Tarabichi, Nogueira, Marchioni, Presutti, Pothier and Ayache6 Single-handed tympanoplasty is initially challenging until the surgeon becomes accustomed to using the instruments with one hand while holding the endoscope with the other. Additionally, frequent cleaning of the lens due to contamination and fogging and difficulty in controlling bleeding with one hand are factors that may prolong operative time.

Although various grafting techniques and graft materials have been described for repairing anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane, graft uptake rates are relatively low in patients with anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane.Reference El-Hennawi, Ahmed, Abou-Halawa and Al-Hamtary8,Reference Iannella and Magliulo10–Reference Demirhan, Yiğit, Hamit and Çakır12 According to a recent literature review, Jalali et al. reported that cartilage graft with comparable audiometric outcomes offers a higher graft uptake rate compared with temporalis fascia.Reference Jalali, Motasaddi, Kouhi, Dabiri and Soleimani11 Chondroperichondrial composite graft is a reasonable option in repairing anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane because it is durable, stable to resorption and resistant to a negative pressure generated by sniffing. Therefore, the authors in the present study used the chondroperichondrial (composed of perichondrium on the lateral side) composite graft in both groups. Both endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty and endoscopic push-through myringoplasty procedures can be performed exclusively with the endoscopic transcanal approach. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study directly comparing the surgical and functional results of these two minimally invasive myringoplasty techniques for repairing anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane.

Both endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty and endoscopic push-through myringoplasty techniques do not require retroauricular skin incision, tympanomeatal flap elevation, canalplasty and malleus manubrium dissection. Post-operative taste impairment associated with chorda tympani nerve injury while entering the middle-ear space is avoided in these techniques. Additionally, the endoscopic push-through myringoplasty technique required tightly packed Gelfoam pieces underneath the graft to prevent medialisation. However, the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty technique does not require Gelfoam packing, which may cause a fullness sensation in the ear and post-operative discomfort. Graft medialisation risk is potentially higher in the push-through technique compared with the butterfly-inlay technique because graft placement is in an underlay fashion. The butterfly-inlay technique provides increased graft stability compared with the push-through technique. We believe that graft placement is technically easier in the butterfly-inlay method compared with the push-through technique because an iatrogenic tear, which may lead to an enlargement of the perforation, may occur while pushing the graft through the perforation, as in our study.

Reported graft uptake rate ranges between 84.4 and 97.4 per cent in patients who underwent endoscopic push-through myringoplasty.Reference Celik, Samim and Oztuna4,Reference El-Hennawi, Ahmed, Abou-Halawa and Al-Hamtary8,Reference Tseng, Lai, Wu, Yuan and Ding13,Reference Loh, Ranguis, Patel and Crossland14 Kim et al. reported a perforation closure rate of 91.3 per cent in patients undergoing modified butterfly-inlay cartilage (comprising one side perichondrium as in our study) myringoplasty.Reference Kim, Park, Suh and Song15 Eren et al. reported a 95.5 per cent graft success rate in patients with anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane who were operated on using the butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty technique.Reference Eren, Tugrul, Ozucer, Veyseller, Aksoy and Ozturan1 The present study is in accordance with the current literature in terms of graft success rate in patients undergoing either endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty (94.1 per cent) or endoscopic push-through myringoplasty (91.8 per cent). Both techniques, with comparable graft success rates, are effective in the closure of anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane. Additionally, our study showed that small- and medium-sized perforations (perforations up to 5.5 mm in the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty group and up to 5 mm in the endoscopic push-through myringoplasty group) did not significantly affect the graft success rate in either group.

• Repairing anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane has always been challenging

• Butterfly-inlay and push-through techniques are minimally invasive, and both can be performed via a pure endoscopic transcanal approach

• Endoscopes skip the narrowest segment of the external auditory canal and make tympanoplasty operations feasible in patients with anterior canal wall protrusion without performing anterior canalplasty

• Endoscopic butterfly-inlay and endoscopic push-through techniques, which offer comparable graft success rates and hearing outcomes, are both effective in the repair of anterior tympanic membrane perforations

• The butterfly-inlay technique, with shorter operative times, is a reasonable alternative to the push-through technique as it provides ease of graft placement and does not require gelfoam packing to support the graft

In studies reporting butterfly-inlay and push-through cartilage myringoplasty outcomes, a significant improvement in ABG values was observed without a remarkable difference in both techniques.Reference Eren, Tugrul, Ozucer, Veyseller, Aksoy and Ozturan1,Reference Celik, Samim and Oztuna4,Reference Eavey7,Reference El-Hennawi, Ahmed, Abou-Halawa and Al-Hamtary8,Reference Loh, Ranguis, Patel and Crossland14–Reference Özgür, Dursun, Terzi, Erdivanlı, Coşkun and Oğurlu16 According to a recent study comparing the functional results of fascia and cartilage graft, Mouna et al. reported that there was no significant difference between fascia and cartilage grafts in terms of auditory functions.Reference Mouna, Khalifa, Ghammem, Limam, Meherzi and Kermani17 We used the chondroperichondrial composite graft with perichondrium preserved on the lateral side in both endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty and endoscopic push-through myringoplasty groups. Consistent with the current literature, this study showed a significant improvement in ABG values in both groups without a statistically significant difference between groups (Table 1).

Most of the studies in the literature suggested that the endoscopic approach provides shorter operative duration in tympanoplasty operations compared with the conventional microscopic approach.Reference El-Hennawi, Ahmed, Abou-Halawa and Al-Hamtary8,Reference Tseng, Lai, Wu, Yuan and Ding13 Kim et al. reported that the average operative time for butterfly-inlay cartilage tympanoplasty was 32.2 minutes.Reference Kim, Park, Suh and Song15 Akyigit et al. reported that the mean operative time of butterfly-inlay myringoplasty in children was 31.7 minutes.Reference Akyigit, Karlidag, Keles, Kaygusuz, Yalcın and Polat18 In this study, the mean operative time of the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty group is comparable with the times reported in the literature. Celik et al. reported an average operative time of 36.1 minutes for anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane using the endoscopic push-through technique, which is similar to our endoscopic push-through myringoplasty results. Our study showed that endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty (mean, 31.5 minutes) had a shorter operative time compared with endoscopic push-through myringoplasty (mean, 41.7 minutes) because packing Gelfoam is not required to support the graft, and graft placement is technically easier in the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty procedure. El-Hennawi et al. reported mean operative times of 37 and 107 minutes for endoscopic push-through and microscopic tympanoplasty procedures, respectively.Reference El-Hennawi, Ahmed, Abou-Halawa and Al-Hamtary8 Anterior canalplasty was performed in 36 per cent of their patients who underwent microscopic tympanoplasty because of anterior canal wall protrusion. Time-consuming anterior canalplasty is not required in the endoscopic transcanal approach because the endoscope allows a complete view of the anterior edge of perforation in patients with anterior canal wall protrusion. Although anterior canal wall protrusion is a factor that may prolong the operative time in microscopic approaches, it does not extend the operative time in endoscopic approaches.Reference El-Hennawi, Ahmed, Abou-Halawa and Al-Hamtary8

In the present study, anterior canalplasty was not required in any of the patients with anterior canal wall protrusion in either endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty or endoscopic push-through myringoplasty groups. Moreover, when the groups were compared separately, there was no significant relationship between the operative time and anterior canal wall protrusion in either group (Table 3). Thus, endoscopic butterfly-inlay or push-through techniques may serve as a reasonable alternative in the treatment of anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane, especially in patients with anterior canal wall protrusion.

During the butterfly-inlay technique procedure, the perichondrium layer is removed from both sides of the cartilage, whereas in the modified butterfly-inlay technique, it is preserved on the lateral side; therefore, cholesteatoma development is theoretically possible due to the existence of perichondrium on the lateral side of the tympanic membrane remnant.Reference Demirhan, Yiğit, Hamit and Çakır12 In this study, cholesteatoma formation was not observed in any patient in the endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty group and has not been reported yet in the literature following modified butterfly-inlay myringoplasty.Reference Ahmed, Raza, Ullah and Shabbir19 The butterfly-inlay technique was applied to the closure of only small perforations when it was first described by Eavey; however, later on, successful results were reported in the repair of medium and large perforations using butterfly-inlay tympanoplasty.Reference Eavey7,Reference Hod, Buda, Hazan and Nageris20 Celik et al. and El-Hennawi et al. also reported comparable graft uptake rates in small-sized anterior perforations with the push-through technique; however, there is no study in the current literature reporting the results of the push-through technique in repairing medium and large-sized perforations.Reference Celik, Samim and Oztuna4,Reference El-Hennawi, Ahmed, Abou-Halawa and Al-Hamtary8 In the present study, we used butterfly-inlay and push-through techniques for repairing small and medium-sized perforations; mean perforation diameters were 4.9 ± 1.7 mm and 4.7 ± 1.1 mm for endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty and endoscopic push-through myringoplasty groups, respectively (p > 0.05). Lastly, the butterfly-inlay technique is inconvenient for repairing marginal perforations, where the remnant of the tympanic membrane is insufficient in stabilising the graft.

Conclusion

Butterfly-inlay and push-through myringoplasty techniques with comparable hearing results are both minimally invasive procedures that can be applied via the endoscopic transcanal approach without tympanomeatal flap elevation. The endoscopic butterfly-inlay cartilage myringoplasty, which is technically easier to use compared with the endoscopic push-through myringoplasty, does not require a sponge buffer to support the graft, provides a shorter operation time and is a reasonable and valid alternative to endoscopic push-through myringoplasty in the repair of anterior perforations of the tympanic membrane.

Acknowledgements

Dr Ersoy Karabay did the statistical analysis of data in the present study.

Competing interests

None declared