Introduction

Acute facial palsy is a relatively rare disease, with an incidence of approximately 30 in 100 000. For its effective treatment, early detection and appropriate management based on aetiology are important.Reference Lee1 The incidence of facial palsy increases with advancing age; the incidence is 0.43 per cent for patients aged 60–69 years and 0.68 per cent for patients aged 70–79 years.Reference Chang, Choi, Kim, Baek and Cho2 Bell's palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome are the most common peripheral causes of acute facial palsy. While Bell's palsy has a relatively good prognosis, facial palsy related to Ramsay Hunt syndrome caused by varicella zoster virus has a poor prognosis.Reference Kondo, Yamamura and Nonaka3

Among the prognostic factors of acute facial palsy, increased age has been associated with poor prognosis or has no significant effect on the prognosis, which makes it difficult to predict the recovery of facial palsy in older adults.Reference Cai, Li, Wang, Niu, Ni and Zhang4,Reference Lee, Byun, Park and Yeo5 The older adult population has rapidly increased with the advancement of healthcare technology and the social welfare system, and this population is predicted to occupy approximately 20 per cent of the overall population in the future.Reference Hyun, Kang and Lee6 Older adults frequently exhibit co-morbidities, such as diabetes or hypertension, and the relatively low immunity of older adults compared to younger adults is likely to entail different clinical outcomes for facial palsy. Abnormal facial movements in older adults may restrict social activities and increase the frequency of depression.Reference Chang, Choi, Kim, Baek and Cho2

To our best knowledge, no study has examined the clinical characteristics of acute facial palsy in older adults. Thus, this study investigated the clinical characteristics and therapeutic outcomes of acute peripheral facial palsy in those aged 60 years or more.

Materials and methods

This study included 30 patients aged 60 years or more who were diagnosed with acute facial palsy at the present hospital between January 2015 and December 2019. Participants who did not agree to the regular follow-up sessions, and those whose systemic health was so poor that the grade of facial palsy could not be accurately assessed, were excluded. The institutional review board at the hospital approved the study (approval number: 2020-03-028), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The clinical characteristics of the patients, including age, sex, aetiology, facial palsy grade, co-morbidity, treatment methods and recovery, were investigated retrospectively. The patients were categorised according to their ages in the following groups: 60–69 years, 70–79 years, 80–89 years, and 90 years or more.

Physical examination and serological tests were used for the diagnosis. Imaging studies were performed on patients with: a history of tumour, a second facial palsy on the same side, trauma to the temporal bone or no sign of recovery after three months. When the aetiology could not be accurately determined, the patient was categorised as having Bell's palsy. Patients with a painful erythematous vesicular rash around the ear were diagnosed with Ramsay Hunt syndrome.

The treatment methods, which involved using various therapeutic agents, were explained to the patients, and the treatment chosen by the patients was administered. The steroid drug prednisolone was administered in the dose of 1 mg/kg for 5 days, and the dose was tapered in the following 5 days. The antiviral drug famciclovir was administered for 7 days. Steroid–antiviral combination treatment was used for patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome, and within 3 days of symptom onset for patients with Bell's palsy.

The extent of facial palsy was assessed using the House–Brackmann grading system. The degree of recovery from facial palsy was evaluated after six weeks, and when the patient showed partial recovery, the evaluation was performed again after three months. The final level of recovery was classified as follows: good recovery, for House–Brackmann grade I or II; partial recovery, for House–Brackmann grade III or IV; and no recovery, in the absence of recovery compared to the time of admission.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 25.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for statistical analyses. The chi-square test was used to compare the effects of therapeutic agents, treatment period, patient age, level of recovery from facial palsy, changes in incidence of facial palsy over 12 months, and recovery between Bell's palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the grade of facial palsy according to co-morbidities. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Age, sex, aetiology and co-morbidity

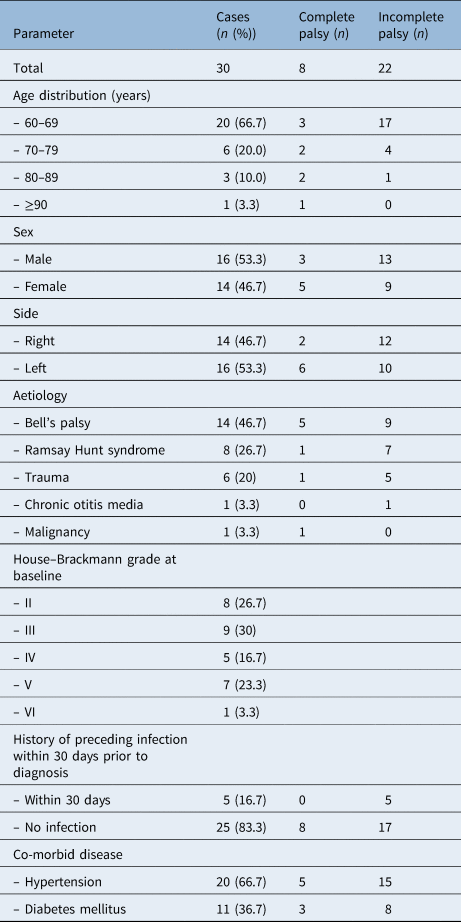

Of the 30 patients, 16 (53.3 per cent) were men and 14 (46.7 per cent) were women. The patients’ mean age was 68.4 ± 9.1 years, and the age distribution was as follows: 20 patients (66.7 per cent) were 60–69 years, 6 patients (20 per cent) were 70–79 years, 3 patients (10 per cent) were 80–89 years, and 1 patient (3.3 per cent) was 90 years or more. With respect to aetiology, Bell's palsy was the most common aetiology, present in 14 cases (46.7 per cent), followed by Ramsay Hunt syndrome in 8 cases (26.7 per cent), trauma in 6 cases (20 per cent), and 1 case (3.3 per cent) each of otitis media and malignant tumour (squamous cell carcinoma of the parotid gland). A history of upper airway infection prior to facial palsy was found in five cases (16.7 per cent). With respect to co-morbidities, 20 cases (66.7 per cent) had hypertension and 11 (36.7 per cent) had diabetes (Table 1). The highest incidence rates over one year were found in January and December, but with no statistically significant difference compared to the other months (chi-square test, p = 0.376; Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Changes in incidence of acute facial palsy in older adults over 12 months (months 1–12 represent January–December, respectively). The highest rates were found in January and December (months 1 and 12).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of older adult patients with acute peripheral facial palsy

Grade of facial palsy and recovery

With respect to facial palsy grade at the time of admission, 8 cases (26.7 per cent) showed complete palsy and 22 cases (73.3 per cent) showed incomplete palsy (Table 1). For the treatment method, 14 patients received a single treatment with a steroid drug, and 11 patients received combination treatment with steroid and antiviral drugs. When a patient with House–Brackmann grade II or III refused drug treatment or had the co-morbidity of diabetes, the patient was monitored without drug treatment (n = 5). Total parotidectomy was performed in the patient with a malignant tumour, and cholesteatoma removal and facial nerve decompression were performed in the patient with otitis media.

The final level of recovery from facial palsy, as assessed after treatment, was as follows: 20 cases (66.7 per cent) of good recovery, 3 cases (10 per cent) of partial recovery and 7 cases (23.3 per cent) of no recovery. No difference in recovery was found between the steroid single treatment group and steroid–antiviral combination treatment group (chi-square test, p = 0.360; Table 2). No recovery was found in 14.3 per cent in the group that received the treatment within one week. However, the rate of cases classified as having no recovery increased to 25.0 per cent in the group that received the treatment after one week (Table 2).

Table 2. Results of treatment for acute facial palsy in older adult patients after three months

Data represent numbers of cases. Note that five patients (who refused drug treatment or exhibited the co-morbidity of diabetes) were monitored without drug treatment.

In older adults, increased age led to a significantly lower level of recovery (chi-square test, p < 0.05; Figure 2). For recovery assessed after treatment, younger age was associated with a higher probability of recovery within three weeks (chi-square test, p < 0.01); in the cases that showed recovery after three weeks, no age difference was found (Table 3). The comparison between older adult patients with Bell's palsy and those with Ramsay Hunt syndrome showed that the level of recovery was significantly higher for older adults with Bell's palsy (chi-square test, p < 0.05; Figure 3).

Fig. 2. Age distribution and recovery of acute facial palsy in older adults. The recovery decreased significantly with increasing age (chi-square test, p < 0.05).

Fig. 3. The changes of House–Brackmann grade between baseline and final assessment in the Bell's palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome groups. Greater improvements (reflected by a lower House–Brackmann grade) were observed in the Bell's palsy group than the Ramsay Hunt syndrome group (chi-square test, p < 0.05).

Table 3. Time of recovery in older adult patients with acute facial palsy

Data represent numbers and percentages of cases, unless indicated otherwise. *n = 20; †n = 6; ‡n = 4; **n = 30. §Indicates significant difference (p < 0.05)

With respect to co-morbidities and the grade of facial palsy, a more severe form of facial palsy was observed in patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome along with the co-morbidity of diabetes (Mann–Whitney U test, p < 0.05). However, no significant difference was found for the final assessment of facial palsy recovery level. In addition, the patients with Bell's palsy showed no statistically significant difference in the level of recovery from facial palsy with regard to co-morbidity (Table 4).

Table 4. Influence of co-morbidities in older adult patients with Bell's palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome

Data represent p-values. *Indicates significant difference (p < 0.05). HB = House–Brackmann; HTN = hypertension; DM = diabetes mellitus

Discussion

Facial palsy may occur because of infection, trauma, tumour, idiopathic causes, or congenital, metabolic or systemic diseases.Reference May and Klein7 Bell's palsy is the most frequent cause of acute facial palsy, and can affect all age groups, although the incidence is relatively low in children aged 10 years or younger and in older adults.Reference Kim, Jung, Jung, Dong, Byun and Park8 In this study targeting older adults, Bell's palsy was the most common aetiology despite the reported low incidence in older adults. Ramsay Hunt syndrome was reported as the second most frequent cause of facial palsy.Reference Adour9 Further, Ramsay Hunt syndrome was the second most common aetiology in this study. We analysed the distribution of acute facial palsy in older adults and observed no difference in terms of the aetiology.

The changes in incidence of acute facial palsy over 12 months is based on viral infection; the incidence increases in cold weather, but decreases in hot weather. However, a contrasting result of no seasonal variation has also been reported.Reference Tovi, Hadar, Sidi, Sarov and Sarov10,Reference De Diego, Prim, Madero and Gavilán11 The 12-month incidence of acute facial palsy in older adults as examined in this study revealed the highest rates in January and December, although there was no statistical significance. This result may indicate that a viral infection, such as upper airway infection, could be an influential factor on the incidence of facial palsy in older adults.

The reported rates of recovery from facial palsy, in those with House–Brackmann grades I–II, was approximately 80–85 per cent in patients with Bell's palsy,Reference Peitersen12,Reference Peitersen13 and 58.7 per cent in patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome.Reference Ryu, Lee, Lee, Park and Yeo14 In this study, 76.7 per cent of patients showed good or partial recovery, and the level of recovery decreased with advancing age.

In older adults, the reduced peripheral blood circulation lowers the level of acute facial palsy recovery, and in the presence of an underlying disease, such as diabetes or hypertension, the recovery level is again low.Reference Devriese, Schumacher, Scheide, de Jongh and Houtkooper15,Reference Yeo, Lee, Jun, Chang and Park16 The grade of facial palsy significantly increases in patients with cardiovascular disease.Reference Chang, Choi, Kim, Baek and Cho2

In this study, the initial House–Brackmann grade of the patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome along with diabetes was higher than that of the patients without diabetes, while the final House–Brackmann grade did not show an intergroup difference. There was no significant difference in House–Brackmann grade in patients with hypertension. These results indicate that among the underlying diseases, diabetes could exert a stronger influence on the incidence of facial palsy than hypertension. Ischaemia or polyneuropathy due to impaired blood circulation may influence the incidence of severe facial palsy in patients with diabetes.Reference Peitersen12 Although the grade of facial palsy does not differ according to the co-morbidity of hypertension, the administration of steroid drugs as the main treatment for acute facial palsy could further increase blood pressure; hence, an adequate management of blood pressure is necessary.Reference Yanagihara and Hyodo17,Reference Jörg, Milani, Simonetti, Bianchetti and Simonetti18 The ability to regenerate the proximal nerves, including the facial nerves, decreases with advancing age; in patients with a history of radiation therapy, the level of regeneration decreases even further.Reference Ducker, Kempe and Hayes19

Electromyography results for facial palsy in older adults have revealed lower amplitude and delayed conduction velocity in older adults compared to young healthy adults, which is due to the relatively smaller muscle fibres in older adults.Reference Boccia, Dardanello, Rosso, Pizzigalli and Rainoldi20 In older adult patients with diabetes, the blink reflex may prolong the latency; hence, the test result should be interpreted carefully.Reference Kiziltan, Uluduz, Yaman and Uzun21

• Bell's palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome were the most common aetiologies of acute facial palsy in older adults

• Increased age led to a significantly lower level of recovery in older adults

• Active early treatment is necessary for achieving good outcomes in older adults

Although extremely rare, older adult patients who present with acute facial palsy may have the aetiology of otitis media, including cholesteatoma;Reference Shinnabe, Hara, Hasegawa, Matsuzawa, Kanazawa and Yoshida22 in this study, a single such case was found. In addition, as shown in this study, malignant tumours of the head and neck, including those of the parotid gland, can cause an acute or progressive facial palsy; hence, the presence of malignant tumours should be evaluated for each case of facial palsy in older adults. Depending on the tumour stage, an appropriate surgical treatment and facial nerve reconstruction may be required.23

Conclusion

Bell's palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome were the most common aetiologies of acute facial palsy in older adults. As partial recovery was observed in many cases, active early treatment is necessary to achieve good outcomes in older adults.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (‘NRF’) grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and Information and Communications Technology; ‘MSIT’) (grant number: 2019R1A2C1002871).

Competing interests

None declared