Introduction

Thyroid surgery has become very common in developed countries, particularly in Europe. Each year, approximately 45 000 thyroidectomies are performed in France, 60 000 in Germany and 4000 in Switzerland.Reference Fortuny, Guigard, Karenovics and Triponez1 Although many surgical techniques have been used, most of today's operations are based on unilateral lobectomy (usually combined with isthmusectomy) or total thyroidectomy. One of the main post-operative complications of thyroid surgery is recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) palsy.Reference Fortuny, Guigard, Karenovics and Triponez2

As surgical techniques have improved over time (i.e. systematic anatomical identification of the laryngeal nerve, strict capsular thyroid dissection with ligature of the thyroid vessels closest to the gland, and intra-operative monitoring of the laryngeal nervesReference Richer and Randolph3–Reference Klopp, Biet, Guillaume-Souaid, Strunski and Page6, post-operative RLN palsy rates have fallen steadily. For thyroid surgery as a whole, the incidence of transient RLN palsy is 5–11 per cent and that of persistent RLN palsy is 1–4 per cent.Reference Christou and Mathonnet2,Reference Jeannon, Orabi, Bruch, Abdalsalam and Simo7

In the present retrospective study of 1026 patients who underwent thyroid surgery for benign lesions, we sought to determine the circumstances in which post-operative RLN palsy occurred.

Materials and methods

This retrospective, single-centre study covered the seven-year period from January 2013 to January 2019.

Ethical considerations

The study was performed in compliance with good clinical practices and the French legislation on ethics in medical research.

Population

During the study period, 1026 patients (760 females and 266 males; mean age of 53 years) underwent surgery for benign thyroid lesions.

Study procedures

The main inclusion criteria were: (1) unilateral lobo-isthmusectomy or total thyroidectomy in a male or female patient; and (2) the presence of benign thyroid disease, including multinodular goitre (i.e. cervicothoracic goitre, toxic goitre and bilateral re-operations), Graves’ disease and thyroiditis. The main exclusion criteria were: (1) pre-operative laryngeal palsy; (2) thyroid cancer; and (3) group VI lymph node dissection.

All patients received the following pre-operative assessments: ultrasound examination of the neck, assays for serum thyroid-stimulating hormone and calcitonin levels, and fibre-optic flexible laryngoscopy.

Surgery was performed by three senior surgeons (AB, CP and VS). All patients underwent thyroid surgery via a small neck incision under general anaesthesia. No muscle relaxants were used, to avoid false-positive responses during neurostimulation. Thyroid lobectomies were performed in a caudocranial direction by capsular dissection after identification of the RLN. The RLN was always monitored during thyroid surgery using the C2 NerveMonitor device (Inomed, Emmendingen, Germany).

Depending on the size of vessels, coagulation was performed with a LigaSure small jaw instrument (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) or surgical wire ligatures (Vicryl size 2.0 or 3.0; Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey, USA). In either case, coagulation was always performed as close as possible to the thyroid gland.

All particular points concerning the specific thyroid surgical procedure have been systematically recorded in thyroidectomy surgical reports in our department since 2012. They are presented in Appendix 1. These data are additional to the surgical record template for thyroid surgery recommended by the Association Francophone de Chirurgie Endocrinienne (French Speaking Association for Endocrine Surgery).8 Moreover, surgeons in our department systematically describe all particular events that occur during surgery at the end of the surgical report, notably in cases of ‘unusual difficulties’.

In order to determine the possible causes of RLN palsy, nine objectively or subjectively judged situations were defined. If present, the causes were systematically mentioned in the surgical report. These causes included: RLN not correctly identified or not identified at all; RLN stretched during dissection; RLN compressed by a goitre; excessively wide-ranging dissection of the RLN; involuntary resection of the RLN; presence of an anatomical variant of the RLN; failure of intra-operative monitoring of the RLN; occurrence of post-operative complications (bleeding or infection); and no apparent cause.

All patients underwent early post-operative fibre-optic laryngoscopy regardless of voice quality, and this was performed again at a one-month follow-up visit. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy was defined as complete immobility of the vocal fold and the arytenoid cartilage. All patients in whom post-operative RLN palsy was detected underwent immediate speech therapy. Patients with a voice disorder or RLN palsy were reviewed every three months until resolution of the disorder or for up to one year. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy was considered to be permanent when it was still present 12 months after surgery. If RLN palsy disappeared, only one additional consultation was performed for confirmation.

Whenever RLN palsy occurred, we investigated several patient- and treatment-related factors, including: particular events during surgery (anatomical variation, ‘abnormal’ bleeding, difficulty finding the RLN, ‘traumatic’ RLN dissection (with involuntary resection of the RLN in some cases)) and/or the occurrence of another post-operative complication (infection or early re-operation for bleeding, i.e. haematoma drainage).

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, mean (range), or frequency (percentage), as appropriate. Between-group comparisons were performed with a chi-square test for categorical variables, and with a student's t-test or a Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables.

Results

In total, 1026 patients (760 women and 266 men; mean age of 53 years (range, 18–81 years)) were included in the study, of whom 809 underwent total thyroidectomy, and 217 underwent unilateral lobectomy with isthmusectomy. Overall, 1835 RLNs were at risk of damage.

Frequency of post-operative recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy

Of the 1026 patients, 46 (4.5 per cent) had post-operative RLN palsy, corresponding to 46 of the 1835 RLNs at risk (2.67 per cent). There were 38 cases (2.07 per cent) of transient RLN palsy and 8 cases (0.44 per cent) of permanent RLN palsy.

Type of surgery and surgical indications

The surgical procedures and indications are summarised in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in the incidence of post-operative RLN according to the type of surgery or thyroid disorder.

Table 1. Surgical indications for thyroid surgery and incidence of post-operative RLN palsy

RLN = recurrent laryngeal nerve

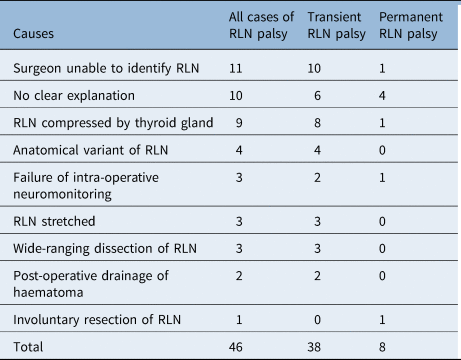

Causes of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy

The circumstances in which post-operative RLN palsy occurred are presented in Table 2. Overall, most of the 38 cases of transient RLN palsy were caused by poor identification of the nerve during surgery (n = 10) or lacked a clear explanation (n = 6). In total, 59 nerves (out of 1835 nerves at risk) were badly or not clearly identified during surgery. Among them, 11 RLN palsies occurred (18.64 per cent), versus 35 (1.97 per cent per cent) among the 1776 clearly identified nerves. The difference in the frequency of RLN palsy occurrences between these two groups (clearly identified nerves vs not clearly identified nerves) was statistically significant (p = 0.0196). Among the eight cases of permanent RLN palsy, one was caused by involuntary section of the nerve and four lacked a clear explanation.

Table 2. Circumstances in which post-operative RLN palsy occurred

Data represent numbers of cases. RLN = recurrent laryngeal nerve

Discussion

According to the literature, the incidence of RLN palsy after thyroidectomy for benign lesions ranges from 1 to 5 per cent (2.18 per cent in the present series) for transient damage and from 0.3 to 0.8 per cent (0.49 per cent in this series) for permanent damage.Reference Steurer, Passler, Denk, Schneider, Niederle and Bigenzahn5,Reference Enomoto, Uchino, Watanabe, Enomoto and Noguchi9,Reference Serpell, Lee, Yeung, Grodski, Johnson and Bailey10 Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy is considered to be permanent when it is still present 12 months after surgery.Reference Laccourreye, Malinvaud, Ménard and Bonfils11

Although marked post-operative hoarseness is the main sign in patients with unilateral vocal fold palsy, a subacute presentation is possible, and voice changes may not be present or obvious for a number of days.Reference Klopp, Biet, Guillaume-Souaid, Strunski and Page6 After studying 154 patients with an initial diagnosis of unilateral RLN palsy after thyroid surgery, Laccourreye et al. reported that 4 individuals (2.6 per cent) had no significant voice problems and even that 8 (17 per cent) had no voice problems at all.Reference Laccourreye, Malinvaud, Ménard and Bonfils11 This is why RLN palsy must be assessed using fibre-optic flexible laryngoscopy before hospital discharge, ideally on post-operative day 1 or 2.Reference Steurer, Passler, Denk, Schneider, Niederle and Bigenzahn5,Reference Klopp, Biet, Guillaume-Souaid, Strunski and Page6,Reference Jeannon, Orabi, Bruch, Abdalsalam and Simo7,Reference Laccourreye, Malinvaud, Ménard and Bonfils11 Furthermore, RLN palsy following thyroid surgery has been a frequent cause of malpractice litigation over the last 20 years, notably in Germany.Reference Dralle, Lorenz and Manchens12

According to the literature, transient or permanent RLN damage has a variety of possible causes, such as clamping, ligature, compression, traction, sectioning, heating (with electrocoagulation systems) and ‘ischaemia’.Reference Serpell, Lee, Yeung, Grodski, Johnson and Bailey10–Reference Snyder, Lairmore, Hendricks and Roberts14

In anatomical terms, the last 2 cm of the RLN extralaryngeal segment is the most susceptible to potential damage.Reference Serpell, Lee, Yeung, Grodski, Johnson and Bailey10,Reference Snyder, Lairmore, Hendricks and Roberts14 As reported by Snyder et al., the main causative mechanism for RLN palsy is excessive traction during dissection of the nerve's motor (anterior) branch in this area;Reference Snyder, Lairmore, Hendricks and Roberts14 the RLN is particularly stretched during thyroid lobe mobilisation (medialisation).Reference Serpell, Lee, Yeung, Grodski, Johnson and Bailey10,Reference Myssiorek13 Moreover, most thyroid surgery patients are placed in a position in which the neck is hyperextended (with a roll or pad placed under the shoulders in some cases). Indeed, neck hyperextension may bring the RLN closer to the surface (particularly the laryngeal penetration area, where it is most vulnerable) and thus promote RLN damage during surgery.Reference Tresallet, Chigot and Menegaux15,Reference Rosato, Avenia, Bernante, De Palma, Gulino and Nasi16

In this series, nine situations were considered to be associated with a risk of nerve damage. We do not intend to put forward a classification of lesion types, but instead propose this list of special circumstances, some of which can occur concomitantly. Although certain lesions are clearly a result of surgical dissection (RLN traction or stripping, resection, electrocoagulation, and so on), others may be related to the thyroid disease itself (e.g. the large size of a cervicothoracic goitre,Reference Tresallet, Chigot and Menegaux15,Reference Daher, Lifante, Voirin, Peix, Colin and Kraimps17 fibrosis or adherences in cases of thyroiditis or re-operations,Reference Chiang, Lin, Wu, Lee, Lu and Kuo18 or bleeding resulting from Graves’ diseaseReference Biet, Zaatar, Strunski and Page19). However, the literature data in this field are inconsistent, particularly concerning Graves’ diseaseReference Tresallet, Chigot and Menegaux15–Reference Page, Cuvelier, Biet and Strunski20 and thyroid re-operations.Reference Chiang, Lin, Wu, Lee, Lu and Kuo18–Reference Page, Cuvelier, Biet and Strunski20

Although the dissection and exposure of the RLN in thyroid surgery has been subject to debate for over 50 years, it now appears that this nerve is not highly vulnerable when carefully dissected. For many years, surgeons were reluctant to dissect the RLN for fear of damaging it. However, it is now broadly acknowledged that precise but safe dissection of this nerve is eminently possible.Reference Page, Foulon and Strunski21 Moreover, we and other researchers consider that simply finding the RLN during surgery is insufficient. On the contrary, the RLN must be fully dissected in the thyroid region (from its emergence in the mediastinal region to the point at which it enters the larynx) to best preserve it from iatrogenic injury,Reference Richer and Randolph3,Reference Dralle, Sekulla, Haerting, Timmermann, Neumann and Kruse4,Reference Page, Cuvelier, Biet and Strunski20,Reference Page, Foulon and Strunski21 even when laryngeal nerves are being monitored during surgery.Reference Hermann, Alk, Roka, Glaser and Freissmuth22–Reference Klopp-Dutote, Biet, Guillaume-Souaid, Strunski and Page24 Intra-operative neuromonitoring of laryngeal nerves can confirm that the RLN has not been damaged after it has been visually identified by dissection; the negative predictive value of intra-operative neuromonitoring for permanent RLN palsy is high (99.2 per cent). Moreover, intra-operative neuromonitoring of the vagus nerve may accurately predict post-operative vocal fold palsy.Reference Klopp-Dutote, Biet, Guillaume-Souaid, Strunski and Page24

• Thyroidectomy is a common surgical procedure, mostly performed to treat benign thyroid disorders

• The main post-operative complication of thyroid surgery is recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) palsy

• The incidence of transient RLN palsy is 5–11 per cent for thyroid surgery overall and 1–4 per cent for persistent RLN palsy, in specialised thyroid surgery centres

• Often, no clear cause is found; several possibly concomitant factors may contribute to post-operative RLN palsy

• Full visual RLN identification during surgery remains the ‘gold standard’ for avoiding nerve damage, even when intra-operative neuromonitoring is used

We consider the main goal of thyroid surgery for benign lesions to be the avoidance of post-operative bilateral RLN palsy. We recommend checking the vagus nerve (which is generally easy to find laterally between the common carotid artery and the internal jugular vein) when performing total thyroidectomy for benign goitre (regardless of the surgical indication) if the RLN is not identified during or after the first lobectomy, and if intra-operative neuromonitoring is available. If the signal is good (i.e. vagus nerve action potential amplitude of more than 100 μV),Reference Randolph, Dralle, Abdullah, Barczynski and Bellantone23 the risk of RLN palsy is close to zero,Reference Randolph, Dralle, Abdullah, Barczynski and Bellantone23,Reference Klopp-Dutote, Biet, Guillaume-Souaid, Strunski and Page24 and the second lobectomy can be performed. If intra-operative neuromonitoring is not available, we recommend stopping the procedure to perform a post-operative laryngoscopy to assess laryngeal function.

Conclusion

Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy after surgery for benign thyroid lesions is probably caused by several factors. Although we studied a large number of cases in the present series, we did not determine clear causes of post-operative RLN palsy other than poor identification of the RLN during surgery, which was a prime cause of post-operative RLN palsy. However, most of our cases of RLN palsy were associated with various intra- or post-operative events. Full visual identification of the RLN during surgery remains the ‘gold standard’ for best avoiding the nerve.

Competing interests

None declared

Appendix 1. Surgical technique – particular points systematically recorded in thyroidectomy surgical reports

Cervical hyperextension: Yes/No

Infrahyoid muscles section: Yes/No

Identification of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN): Right side/Left side Yes/No

Complete dissection of the RLN in the thyroid region: Right side/Left side Yes/No

Partial dissection of the RLN (distal course): Right side/Left side Yes/No

Presence of a Zuckerkandl tubercle: Right side/Left side Yes/No

Anatomical variation of the RLN: Right side/Left side Yes/No

– Nerve superficial to the inferior thyroid artery: Yes/No

– Nerve deep to the inferior thyroid artery: Yes/No

– Nerve divided: Yes/No Number of branches

– Nerve ‘abnormally thin’: Yes/No

– Non-recurrent inferior laryngeal nerve: Yes/No

Intra-operative neuromonitoring of the RLN: Right side/Left side Yes/No

– Value of the action potential amplitude (in μV) before lobectomy

– Value of the action potential amplitude (in μV) after lobectomy

– Loss of signal after lobectomy: Yes/No

Intra-operative neuromonitoring of the vagus nerve: Right side/Left side Yes/No

– Value of the action potential amplitude (in μV) before lobectomy

– Value of the action potential amplitude (in μV) after lobectomy

– Loss of signal after lobectomy: Yes/No

Occurrence of an RLN lesion: Right side/Left side Yes/No

– Involuntary section

– Stretching

Identification of the external laryngeal nerve: Right side/Left side Yes/No

Identification of parathyroid glands: Yes/No Right side/Left side

– Number of identified glands

– Position of identified glands: High (cricothyroid area)/ Medium (inferior thyroid division area)/ Low (pretracheal or under the inferior edge of the thyroid lobe)

Re-implantation of parathyroid gland in the sternocleidomastoid muscle: Yes/No Right side/Left side