Introduction

The incidence of paediatric cholesteatoma is reported to be three to six per 100 000.Reference Sohet and De Jong1 Cholesteatoma in children can be congenital or acquired. The vast majority of cases are the latter.Reference Friedberg2 Acquired cholesteatoma usually presents with otorrhoea and hearing loss. Involvement of the facial nerve or vestibular system can cause facial nerve paresis, vertigo and/or sensorineural hearing loss. However, Pain is an uncommon symptom.

The aims of paediatric cholesteatoma surgery are: (1) disease clearance, (2) preservation or restoration of hearing, and (3) prevention of recurrent disease. It is not always possible to achieve all these goals at initial surgery; as a result, residual and recurrent disease are not uncommon in the management of paediatric cholesteatoma.

The management of paediatric cholesteatoma poses a greater challenge than adult disease, as children tend to present with aggressive disease and have a higher recurrence rate.Reference Fageeh, Schloss, Elahi, Tewfik and Manoukian3 The two main factors implicated in recurrent paediatric disease are persistent eustachian tube dysfunction and a well pneumatised mastoid complex, as opposed to sclerotic mastoids in adults.

There is constant debate on the appropriate surgical technique for paediatric cholesteatoma. The two main procedures described are the intact canal wall mastoidectomy and the traditional canal wall down mastoidectomy. For both techniques, enthusiasts report adequate disease clearance, reduced recurrence rates and comparable hearing outcomes.Reference Brackmann, Schelton, Arriaga and Arriaga4 Our experience has primarily been in canal wall down mastoidectomy techniques, and also, to a more limited degree, inside to outside mastoidectomy comprising atticotomy or atticoantrostomy.Reference Nikolopoulos and Gerbesiotis5

Materials and methods

This study was designed as a retrospective case note review. Patient information was collected from hospital operating theatre records. All children who underwent mastoid exploration at the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow, Scotland, UK, between January 1999 and December 2009 were studied.

Data collected included patient demographics, type of surgery, pre- and post-operative audiograms, post-operative complications, and indication for revision surgery. Pure tone thresholds were recorded at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz.

Intra-operative findings, such as the disease extent, ossicular chain involvement, and state of the facial nerve and lateral semicircular canals, were also recorded.

Recurrent cholesteatoma was defined as a newly formed retraction pocket extending to the attic, while residual cholesteatoma was recorded if an epithelial pearl was seen arising from a remnant of cholesteatoma matrix.Reference Sheehy, Brackmann and Graham6

A high facial ridge was defined as a distance of more than 6 mm between the annulus (at a 6 o'clock position) and the facial ridge.Reference Wormald and Nilssen7 This was recorded as a clinical finding when keratin debris was seen arising in a sump behind the posteroinferior canal wall.

An inadequate meatoplasty was recorded when the entire tympanic membrane and mastoid cavity could not be visualised.

All data for primary and revision procedures were recorded separately. Audiometric analysis was performed based on guidelines published by the Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium of the American Academy of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery.Reference Monsell8

Cholesteatoma recurrence rates in the revision and non-revision groups were statistically analysed using Fisher's exact test. A p value of less than 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

Primary surgery

We identified 99 patients who underwent 101 primary mastoid ear operations for cholesteatoma. Two patients had bilateral disease. There were 53 females and 46 males, with an age range of two to 18 years. The mean age at surgery was 9.5 years.

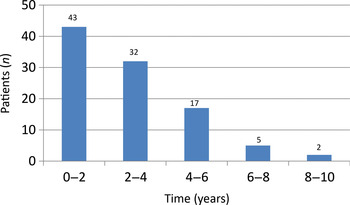

All primary surgical procedures involved patients with cholesteatoma. Seventy-seven children presented with intermittent otorrhoea, 17 with deafness alone and five with acute mastoiditis. Ninety-four ears were diagnosed with acquired cholesteatoma and seven with congenital cholesteatoma. The follow-up period for all patients is shown in Figure 1. High resolution computed tomography (CT) imaging of the petrous temporal bones was performed in 25 patients.

Fig. 1 Patient follow-up period, for 99 patients.

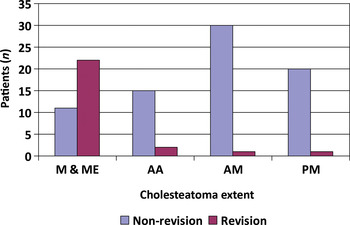

The disease extent at primary surgery is shown in Figure 2. Sixty-one cases involved an endaural approach and 40 a postaural approach. The primary surgical procedures comprised 54 modified radical mastoidectomies, 33 atticotomies, 11 atticoantrostomies, two radical mastoidectomies and one extended radical mastoidectomy. In suitable patients, hearing reconstruction was performed using either temporalis fascia or tragal cartilage, or both. Facial nerve canal dehiscence and lateral semicircular canal dehiscence were observed in 13 and 10 patients, respectively.

Fig. 2 Extent of cholesteatoma at primary surgery in non-revision and revision cases. M & ME = entire mastoid and middle-ear cleft; AA = attic and antrum; AM = anterior mesotympanum; PM = posterior mesotympanum

The state of the ossicles is summarised in Table I. Ossicular chain involvement was seen in 63 ears, while 38 ears had no ossicular chain involvement. Ossicular erosion was analysed as an independent factor predicting recurrence in revision and non-revision groups, but did not appear to be clinically significant (p = 0.121).

Table I Ossicle score at primary surgery

Data represent patient numbers. Ossicle score: 0 = intact; 1 = partial erosion; 2 = complete erosion. p > 0.05, disease recurrence in non-revision vs revision group.

Hearing thresholds were ≤30 dB in 53 patients, ≤50 dB in 31 and ≤70 dB in 15. The mean pre- and post-operative air–bone gaps for all children were 32.44 and 27.56 dB, respectively, giving a mean improvement of 4.8 dB.

Post-operative complications included wound infection (five patients), keloid scarring (three), persistent otorrhoea (two) and wound dehiscence (one). Ninety ears were dry following primary surgery, with no complaints of otorrhoea. However, intermittent otorrhoea was seen between six and 12 months post-operatively in five ears, between 12 and 18 months in four ears, and up to two years in two ears.

Revision surgery

Twenty-five of our patients underwent revision mastoidectomy, resulting in a revision rate of 25 per cent. The time to recurrence was one to three years in 17 ears, three to six years in five ears, and six to nine years in three ears. Twenty-one of the 25 cases had retraction pockets. Interestingly, eight of the 25 ears in the revision group demonstrated a spontaneous hearing improvement, on average 18 months following primary surgery. Computed tomography imaging in these patients was equivocal, with no definite evidence of cholesteatoma. The mean air conduction threshold improved by 12.98 dB. In contrast, no child in the non-revision group showed any spontaneous hearing improvement.

A further 11 ears in our series had a planned ‘second look’ procedure between eight and 12 months post-operatively. Second look surgery was performed if the operating surgeon felt that all disease could not be cleared adequately at primary surgery (four cases), or if disease was intentionally left behind over a dehiscent facial nerve (three cases) or stapes footplate (four cases). All children undergoing planned second look procedures were found to have cholesteatoma.

The presenting complaint in children who underwent revision mastoidectomy was recurrent otorrhoea. A decision to proceed to revision surgery was based on clinical grounds, as CT imaging was unhelpful (as previously mentioned).

The indication for revision was recurrent disease in 12 ears, a high facial ridge in five ears and inadequate meatoplasty in four ears. The latter two groups were also observed to have recurrent disease, in addition. Four patients were found to have generalised middle-ear mucosal oedema but no obvious keratin debris. A high facial ridge (p = 0.001) and inadequate meatoplasty (p = 0.005) appeared to be independent risk factors predicting disease recurrence, comparing the revision and non-revision groups.

The mean pre- and post-operative air–bone gaps were 42.56 and 39.20 dB, respectively.

Recurrent disease was seen in 20 (80 per cent) cases with ossicular erosion and 22 (88 per cent) cases with disease involving the entire mastoid and middle-ear cleft, at initial surgery. However, ossicular erosion (p = 0.81) and disease extent (p = 0.51) at primary surgery did not appear to be significant risk factors in predicting cholesteatoma recurrence, comparing the revision and non-revision groups.

Discussion

The aim of paediatric cholesteatoma surgery is disease clearance with preservation or restoration of hearing.

As previously mentioned, children with cholesteatoma tend to present with more aggressive disease, compared with adults. Recurrence rates of 7 to 57 per cent have been reported for paediatric cholesteatoma.Reference Ahn, Seung, Chang and Kim9 In a review of over 700 patients, Tos and Lau did not observe any difference in recurrence rate between intact canal wall and canal wall down mastoidectomy techniques.Reference Tos and Lau10 Factors such as surgeon experience, high facial ridge, inadequate meatoplasty, ossicular chain involvement and cholesteatoma extent have been reported to correlate highly with disease recurrence.Reference Monsell8, Reference Roger, Denoyelle, Chauvi, Schlegel-Stuhl and Garabedian11–Reference Rosenfiled, Moura and Bluestone14

In our study, eight of 25 ears demonstrated spontaneous improvement in air conduction thresholds 12 to 18 months following primary surgery. On re-exploration, all eight cases had recurrent disease. No child in the non-revision group demonstrated spontaneous improvement in hearing thresholds. Hence, we believe that spontaneous improvement in hearing thresholds following cholesteatoma surgery should alert the clinician to the possibility of recurrent disease.

Silvola and Palva reported a correlation between post-operative retraction pockets and recurrence.Reference Silvola and Palva15 In our series, 64 per cent (16/25) of cases demonstrated recurrent disease within retraction pockets. Traditionally, canal wall down mastoidectomy techniques have been thought to be associated with poorer hearing outcomes, compared with intact canal wall mastoidectomy; however, several reports have challenged this belief.Reference Roden, Honrubia and Weit16–Reference Toner and Smyth18

Our department provides a service for the West Central Scotland, Greater Glasgow and Glasgow City regions, which together constitute a population with a lower socio-economic and educational profile, compared with the rest of the UK and Europe.Reference Gray and Leyland19, Reference Gray20 Hence, factors such as aggressive disease, late presentation and unreliable follow up have prompted us to favour canal wall down mastoidectomy procedures. Although previous reports have suggested that intact canal wall mastoidectomy techniques are associated with higher rates of residual and recurrent disease, we accept that proponents of these techniques report comparable results with regards to disease clearance, hearing outcomes and recurrence rates.

Conclusions

Children present with aggressive cholesteatoma middle ear disease. Extent of disease and ossicular chain involvement are associated with an increased risk of recurrence. Spontaneous improvement in hearing thresholds following cholesteatoma surgery should raise suspicion of recurrent disease.