Introduction

We present two cases of patients with high and dehiscent jugular bulbs extending into the external ear canal. To our knowledge, there has been only one previously reported case of a high, dehiscent jugular bulb protruding into the external ear canal. We present our patients' radiological findings, including a magnetic resonance venogram image (an imaging modality not previously described), and we discuss the relevant literature.

Case reports

Case one

A 52-year-old woman presented with an eight-year history of a moderate, right-sided, sensorineural hearing loss and a two-year history of intermittent, right otorrhoea, without any associated otalgia, dizziness, tinnitus or facial nerve weakness.

Examination of the right ear revealed granulation at the postero-superior aspect of the tympanic membrane.

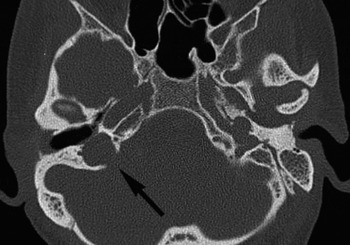

Computed tomography (CT) scanning of the patient's temporal bones reportedly demonstrated opacification of the middle ear, involving the ossicles, round and oval windows, and tympanic membrane, with dehiscence of the posterior part of the tegmen. The mastoid air cells were opacified. Findings were consistent with cholesteatoma or granulation tissue.

The patient was admitted for a right mastoid exploration. On inspection of the external ear canal, a large area of granulation tissue was noted to arise from the attic. The lateral component of a tympanomeatal flap was elevated. Whilst still lateral to the annulus, brisk venous bleeding was encountered, precluding further exploration of the ear. The patient was placed in a head-down position and the ear canal was packed with bismuth iodoform paraffin paste.

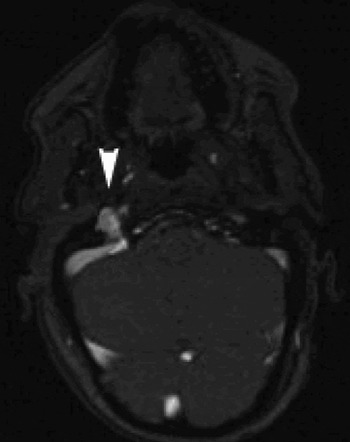

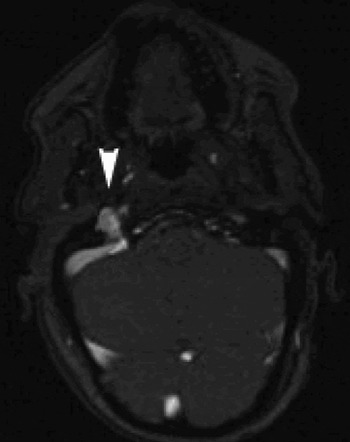

Further review of the CT scan revealed a high, dehiscent jugular bulb protruding into the external ear canal (Figure 1). Following successful haemostasis with bismuth iodoform paraffin paste packs, the patient underwent a magnetic resonance venogram, which demonstrated a high jugular bulb with extension into the floor of the external ear canal and minimal extension into the hypotympanum (Figure 2). No further surgery was attempted.

Fig. 1 Case one: axial, high resolution computed tomography image of the right petrous temporal bone. Arrow denotes high, dehiscent right jugular bulb projecting into the right external ear canal and middle-ear cavity.

Fig. 2 Case one: axial magnetic resonance venogram image of the right petrous temporal bone. Arrowhead denotes high, dehiscent right jugular bulb projecting into the right external ear canal and middle-ear cavity.

At the time of writing, the patient was under continuing close follow up to monitor her condition, with no plans for further surgery unless her condition worsened.

Case two

A 42-year-old man was referred with a four-month history of left-sided, conductive hearing loss, combined with intermittent tinnitus and loss of balance.

Otoscopy revealed a blue area in the posterior portion of the tympanic membrane.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast was requested to exclude a glomus tumour. This scan showed altered signal around and within the left jugular vein, of uncertain significance, and a CT scan was suggested. High resolution CT images demonstrated a high, dehiscent left jugular bulb, with loss of the bony wall between the jugular bulb and the left external ear canal and hypotympanum (Figures 3 and 4). A magnetic resonance venogram scan was organised and the referring surgeon contacted and informed of the findings. The magnetic resonance venogram confirmed the findings of the CT scan. There was no evidence of a glomus tumour.

Fig. 3 Case two: axial, high resolution computed tomography image of the left petrous temporal bone. Arrowhead denotes a high, dehiscent left jugular bulb projecting into the left external ear canal and middle-ear cavity.

Fig. 4 Case two: coronal, high resolution computed tomography image of the left petrous temporal bone. Arrowhead denotes a high, dehiscent left jugular bulb projecting into the left external ear canal and middle-ear cavity.

Further review of the patient's previous medical notes revealed that he had undergone a tympanotomy in 1976, at which time the surgeon had noted a vascular anomaly in the middle ear, thought to be a large sigmoid sinus.

A full and frank discussion with the patient ensued, with an explanation of the imaging results. He was advised not to have surgery for the high, dehiscent jugular bulb. The patient was happy that no further action was needed, and was discharged from the clinic.

Discussion

Vascular anomalies described within the temporal bone include a high jugular bulb, a dehiscent jugular bulb, a diverticulum associated with the jugular bulb, an anterior location of the sigmoid sinus and a dehiscent internal carotid artery.Reference Atilla, Akpek, Uslu, Ilgit and Işik1, Reference Harnsberger, Hudgens, Wiggins, Davidson and Harnsberger2 The jugular bulb is formed by entrance of the sigmoid sinus into the superior part of the internal jugular vein, and usually lies below the posterior part of the floor of the middle ear; however, its normal position is variable.Reference Moore3

The most common vascular anomaly of the petrous temporal bone is a high jugular bulb.Reference Towbin, Ball, Benton and Han4, Reference Ford5 The definition of what constitutes this anomaly varies within the literature, ranging from intrusion into the middle ear,Reference Moore3 through extension above the inferior rim of the bony annulus,Reference Tomura, Sashi, Kobayashi, Hirano, Hashimoto and Watarai6 to rising above the round window and basal turn of the cochlea.Reference Atilla, Akpek, Uslu, Ilgit and Işik1, Reference Koesling, Kunkel and Schul7 The reported incidence of a high jugular bulb ranges from 3.5 to 34 per cent.1,4,6–8 This anomaly has been reported to be twice as common on the right side than the left, with a much smaller incidence of bilateral high jugular bulbs.Reference Atilla, Akpek, Uslu, Ilgit and Işik1

A high jugular bulb is vulnerable during surgery. Case reports have described damage and resulting profuse haemorrhage as a result of myringotomy,Reference Moore3, Reference Ford5, Reference Tomura, Sashi, Kobayashi, Hirano, Hashimoto and Watarai6, Reference Subotić8 elevation of the inferior annulus,Reference Moore3 elevation of a tympanomeatal flapReference Moore3, Reference Subotić8 and removal of granulation tissue during middle-ear surgery.Reference Subotić8 Indeed, intrusion of a high jugular bulb into the middle ear has been well described.Reference Moore3 The only reported case of damage to a high jugular bulb during external ear canal surgery has been described by Moore.Reference Moore3 In this case, following an endaural incision, haemorrhage occurred on elevation of the tympanomeatal flap near the annulus.

A dehiscent jugular bulb is defined as a normal venous variant with superior and lateral extension of the jugular bulb into the middle-ear cavity through a dehiscent sigmoid plate.Reference Harnsberger, Hudgens, Wiggins, Davidson and Harnsberger2 It is more commonly seen in association with a high jugular bulb, and has a reported incidence of 1–7 per cent.Reference Atilla, Akpek, Uslu, Ilgit and Işik1, Reference Harnsberger, Hudgens, Wiggins, Davidson and Harnsberger2, Reference Tomura, Sashi, Kobayashi, Hirano, Hashimoto and Watarai6, Reference Koesling, Kunkel and Schul7 This variant is clearly more vulnerable to injury during surgery, due to its incomplete bony covering and resultant lack of protection – it is separated from the middle-ear cavity only by a thin layer of mucosa.Reference Harnsberger, Hudgens, Wiggins, Davidson and Harnsberger2, Reference Moore3

• A high and/or dehiscent jugular bulb opening into the middle-ear cavity has frequently been described

• Definitions of a high jugular bulb vary within the literature

• The reported incidence of a high jugular bulb varies from 3.5 to 34 per cent

• High and dehiscent jugular bulbs are vulnerable to damage during surgery

• High and/or dehiscent jugular bulbs can protrude into the external ear canal

• Such cases can present silently

• Intra-operative bleeding from high or dehiscent jugular bulbs should be managed appropriately

• The two cases presented demonstrate the importance of full, accurate assessment of pre-operative computed tomography scans by both the radiologist and the surgeon

When assessing patients for surgery, surgeons should consider the potential for vascular anomalies. History-taking should assess for hearing loss and venous tinnitus (characteristically pulsatile, particularly on exertion or stress).Reference Moore3, Reference Ford5 Abnormal otoscopic findings may include a visible mass in the ear canal or a blue discolouration behind the tympanic membrane,Reference Atilla, Akpek, Uslu, Ilgit and Işik1, Reference Moore3, Reference Towbin, Ball, Benton and Han4 as in our second patient, who was symptomatic. However, it is important to recognise that vascular anomalies can occur in the absence of these features – our first patient had a silent presentation. In the event of haemorrhage from a high or dehiscent jugular bulb, the patient should immediately be placed in a head-down position to minimise the risk of air embolism;Reference Moore3 haemostasis can normally be achieved by placing a pack in the ear.

These cases also illustrate the importance of close assessment of the pre-operative CT scans by both the radiologist and the surgeon. In our first patient, the high, dehiscent jugular bulb evident on the pre-operative CT was missed initially, perhaps due to concentration on the area of suspected cholesteatoma. This demonstrates the importance of close inspection of all anatomical regions on a pre-operative scan, not simply the area in question. However, in our second case, a high, dehiscent jugular bulb was noted and the surgeon warned not to attempt any procedure until further radiological assessment had been carried out.