Introduction

Basaloid squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) are rare tumours which are usually found in the aerodigestive tract. They differ from epidermoid carcinomas in their histological appearance and potentially aggressive clinical characteristics. Only a few cases of basaloid SCCs in the ear, nose or throat have been described since the first such report in 1986.Reference Wain, Kier, Vollmer and Bossen1

In the French language literature,Reference Soriano, Righini, Faure, Lantuejoul, Colonna and Bolla2, Reference Chavanis, Chavanon, Chaffanjon, Lantuejoul, Reyt and Brichon3 cases have been rarely reported but well defined; in the English language literature, reports have been more numerous but exact numbers difficult to evaluate (as certain cases have been reported in several different studies).

Most authors report a poor outcome for head and neck basaloid SCC. Histological and immunohistochemical analysis is therefore an important tool in establishing a reliable diagnosis.

We report our experience of 18 cases of basaloid head and neck SCC treated between 1986 and 2006, focussing on this lesion's aggressive clinical course and its histopathological diagnosis and management.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study included a total of 18 cases treated between 1986 and 2006 in our ENT department. Study inclusion was based on a histological diagnosis of basaloid SCC, according to the criteria defined by Wain et al. Reference Wain, Kier, Vollmer and Bossen1

Clinical data regarding age, gender, alcohol and tobacco use, stage, treatment, and follow up were obtained from our institution's computerised database. Lesions were classified using the tumour-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system,Reference Sobin and Wittekins4 following clinical examination, endoscopy, and computed tomography (CT) of the neck, pharynx, larynx and sinuses. Magnetic resonance imaging was carried out in one case of a tumour located in the nasal sinus. Cases suspicious for lung or liver metastasis received a routine physical examination, liver blood biochemistry analysis, lung X-ray, and chest and abdominal CT scanning; some cases also received liver ultrasonography. From 2000 onwards, patients also underwent routine cervico-thoracic CT scanning.

Routine histological examination was performed in all patients. Six patients (30 per cent) also received additional immunohistochemical tests analysing smooth muscle actin, neuron-specific enolase, PS 100, synaptophysin, vimentin, chromogranin and cytokeratins (i.e. KL1, MNF 116, 34βE12, CAM 5.2 and EMA).

The survival rate was analysed using the Kaplan–Meier test.

Results

Demographic and clinical data

The mean patient age was 61 years (range 52–87 years) and the sex ratio was 3.5 (14 men and four women). There were 13 smokers, of whom nine had a previous medical history of alcohol abuse. One patient was a passive smoker. One patient had a previous medical history of cervical irradiation for SCC, six years prior to the appearance of basaloid SCC.

Table I summarises the patients’ disease localisation, TNM stage at diagnosis, metastasis and outcome. All patients treated surgically for basaloid SCC also underwent cervical dissection for lymph nodes. Basaloid SCC occurred most frequently in the larynx (seven cases) and hypopharynx (seven cases). Fourteen (78 per cent) patients had either stage three or four disease, and 50 per cent of all 18 cases had clinical or radiological lymph node involvement at diagnosis. The mean follow-up time was 33 months (range two to 140 months).

Table I Clinical and outcome data

*Primary (M1) or secondary. Pt no = patient number; TNM = tumour-node-metastasis staging; DOD = died of disease; mth = months; hypo = hypopharynx; S = surgery; RT = radiotherapy; R = recurrence; yr = years; NR = no apparent recurrence after the last carcinogenic episode; CT = chemotherapy; oro = oropharynx; RT = radiotherapy; LR = alive with recurrence; CT–RT = concurrent CT & RT; DC = died of intercurrent disease; LNR = lymph node recurrence

The most common treatment was combined surgery and radiotherapy (eight cases); some of these patients also received chemotherapy with cisplatin (three cases). In the other cases, treatment consisted of surgery alone (two cases), radiotherapy alone (one case), radiotherapy and chemotherapy (cisplatin) (one case), polychemotherapy (cisplatin and fluorouracil) (one case), and palliative treatment alone (one case). Adjuvant chemotherapy was added to post-operative radiotherapy in cases in which histopathological analysis showed surgical margin involvement, angiomatous and/or perineural invasion, involvement of more than three lymph nodes, or lymph node capsular rupture.

Regarding outcomes, there were three cases of local recurrence (one in a maxillary sinus and two in the pharynx) and one of regional recurrence (involving one lymph node in the Ha area). Seven (39 per cent) patients had metastasis. The principal site of metastasis was the lung in five cases, the liver in one case and the skull base in one case.

One patient (number 8, Table I) presented with synchronous lesions in the larynx and bronchus (of similar histological type). Another patient (number 12) presented with a metachronous lesion in the oropharynx, followed six years later by a basaloid SCC of the lateral piriform sinus wall.

Survival rates at one, three and five years were 78, 22 and 5 per cent, respectively, with a median survival time of 23 months from the time of diagnosis. Only one patient (number 9) died of intercurrent disease. In our institution, the survival outcomes for conventional SCC was 28 per cent for pharyngeal and oral cavityl and 45 per cent for laryngeal lesions, in contrast the survival of head and neck basaloid squamous cell carcinoma.

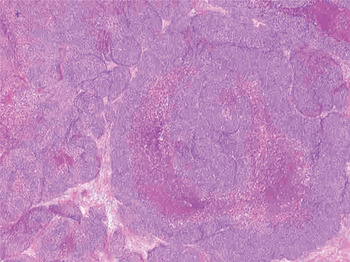

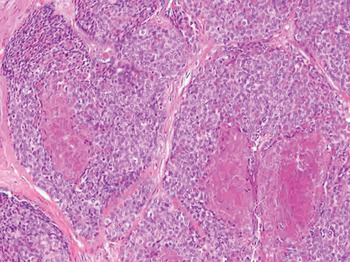

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry (Figs 1–3)

Histopathological analysis was performed according to the method of Wain et al.,Reference Wain, Kier, Vollmer and Bossen1 with the exception of one case in which cystic spaces were found.

Immunohistochemical test results are presented in Table II. Positive immunostaining for the epithelial markers 34βE12, KL1 and MNF116 was seen in all of the six tested cases. Of these six cases, positive staining for CAM 5.2 and neuron-specific enolase was present in 70–75 per cent, and positive staining for chromogranin, PS100, actin, vimentin and synaptophysin was seen in 14–40 per cent. Positive staining for neuroendocrine markers (i.e. chromogranin and synaptophysin) was observed in only one case.

Fig. 1 Photomicrograph showing lobules of basaloid cells with central comedonecrosis. (Haematoxylin eosin safran; original magnification ×2.5)

Fig. 2 Photomicrograph showing central comedo-style necrosis within a basaloid nest. (Haematoxylin eosin safran; original magnification ×10)

Fig. 3 Photomicrograph showing abundant intercellular hyaline globules conferring a cribriform-like pattern. (Haematoxylin eosin safran; original magnification ×40)

Discussion

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma is a particular variant of SCC known to occur in a variety of anatomical sites, including the upper aerodigestive tract and head and neck. The first 10 cases of upper aerodigestive tract lesions were described by Wain et al. Reference Wain, Kier, Vollmer and Bossen1 in 1986. Since then, more than 200 cases of basaloid SCC of the head and neck have been reported.Reference Soriano, Righini, Faure, Lantuejoul, Colonna and Bolla2, Reference Chavanis, Chavanon, Chaffanjon, Lantuejoul, Reyt and Brichon3, Reference Batsakis and El Naggar5–Reference Ferlito, Altavilla, Rinaldo and Doglioni34 Most of these cases were located in the upper aerodigestive tract.Reference Wain, Kier, Vollmer and Bossen1, Reference Banks, Frierson, Mills, George, Zarbo and Swanson6–Reference Seidman, Berman, Yost and Iseri10, Reference Raslan, Barnes, Kraus, Contis, Killeen and Kapadia12–Reference De Sampaio Góes, Oliveira, Dorta, Nishimoto, Landman and Kowalski29

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma can also be encountered in other sites, such as the oesophagus,Reference Tauchi, Kakudo, Machimura and Makuuchi35–Reference Li, Zhang, Wen, Cowan, Hart and Xiao39 lung and bronchus,Reference Brambilla, Moro, Veale, Brichon, Stoebrer and Paramelle40–Reference Lin, Harkin and Jagirdar42 thymus,Reference Suster and Rosai43 anus,Reference Dougherty and Evans44 sinonasal tract,Reference Wieneke, Thompson and Wenig45–Reference Oikawa, Tabuchi, Nomura, Okubo, Wada and Iijima47 and uterine cervix.Reference Morice and Ferreiro48

Clinical evaluation

The basaloid SCC patient population is similar to the head and neck conventional SCC patient population in terms of sex ratio (with a male preponderance) and mean age (60 years).Reference Wain, Kier, Vollmer and Bossen1, Reference Banks, Frierson, Mills, George, Zarbo and Swanson6, Reference Luna, El Naggar, Parichatikanond, Weber and Batsakis8, Reference Ide, Shimoyama, Horie and Kusama24, Reference Coletta, Cotrim, Almeida, Alves, Wakamatsu and Vargas28, Reference Wieneke, Thompson and Wenig45, Reference Altrabulsi, Carrizo and Luna49

Most of our patients presented with advanced stage disease, according to the guidelines established by the UICC. Similarly, previously reported cases of basaloid SCC have primarily presented at an advanced stage, with frequent metastasis.Reference Wain, Kier, Vollmer and Bossen1, Reference Banks, Frierson, Mills, George, Zarbo and Swanson6, Reference Luna, El Naggar, Parichatikanond, Weber and Batsakis8, Reference Ereño, Lopez, Sanchez and Toledo13, Reference Ferlito, Devaney and Rinaldo15, Reference Ide, Shimoyama, Horie and Kusama24, Reference Prasad, Kaniyur, Devan and Kedakalathil31

The risk factors for head and neck basaloid SCC are unclear. Tobacco and alcohol consumption have been implicated by Banks et al.,Reference Banks, Frierson, Mills, George, Zarbo and Swanson6 but not by Wieneke et al.Reference Wieneke, Thompson and Wenig45 The involvement of cervical radiationReference Wan, Chan and Tse22 and viral carcinogens (i.e. human papilloma virus (HPV) and herpes simplex virus)Reference De Araujo, de Sousa, Carvalho and de Araujo50 has also been reported. Alcohol and tobacco consumption seems to be present in the same proportion of basaloid SCC patients and conventional SCC patients.Reference Soriano, Faure, Lantuejoul, Reyt, Bolla and Brambilla51 Recent articlesReference Cabanillas, Rodrigo, Ferlito, Rinaldo, Fresno and Aguilar33, Reference Begum and Westra52 have reported that HPV 16 plays a role in head and neck basaloid SCC development. As in conventional SCC, HPV 16 seems to be more frequent in oropharyngeal basaloid SCC than in non-oropharyngeal basaloid SCC, and its presence is associated with an increased survival rate. Our study did not assess HPV.

Table II Immunohistochemical test results

Basaloid SCC requires aggressive, multimodality treatment incorporating surgery (of the lesion and lymph nodes), radiotherapy and, in most cases, chemotherapy.Reference Wain, Kier, Vollmer and Bossen1, Reference Banks, Frierson, Mills, George, Zarbo and Swanson6, Reference Barnes, Ferlito, Altavilla, Macmillian, Rinaldo and Doglioni7, Reference Raslan, Barnes, Kraus, Contis, Killeen and Kapadia12, Reference Wieneke, Thompson and Wenig45 In our study, chemotherapy was associated with curative treatment in cases with poor histopathological prognostic factors, as has been reported for Head and neck conventional SCC by Soriano et al.Reference Soriano, Faure, Lantuejoul, Reyt, Bolla and Brambilla51

Histopathological analysis

Basaloid SCC has distinct, specific histopathological characteristics.Reference Wain, Kier, Vollmer and Bossen1, Reference Banks, Frierson, Mills, George, Zarbo and Swanson6 Histopathological diagnostic criteria for this tumour were originally defined by Wain et al.,Reference Wain, Kier, Vollmer and Bossen1 and have been modified several times.Reference Banks, Frierson, Mills, George, Zarbo and Swanson6–Reference Luna, El Naggar, Parichatikanond, Weber and Batsakis8, Reference Muller and Barnes14, Reference Wieneke, Thompson and Wenig45

The differential diagnosis of basaloid SCC includes adenoid cystic carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, small cell undifferentiated carcinoma, basal cell adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma.Reference Wieneke, Thompson and Wenig45 The similarity to adenoid cystic carcinoma is only superficial;Reference Banks, Frierson, Mills, George, Zarbo and Swanson6 in the present study the correct diagnosis is made by meticulous histological examination.

Immunohistochemical analysis enables the differentiation of basaloid SCC from other lesions; however, immunostaining assessment does not appear to be useful in differentiating basaloid SCC from adenoid cystic carcinoma.Reference Wieneke, Thompson and Wenig45

Immunostaining assessment

Several antibodies have been evaluated to determine their immunoreactivity to basaloid SCC, in order to differentiate this tumour from other cancers. The antibody against 34βE12 (an antibody specific for high molecular weight cytokeratins 1, 5, 10 and 14) seems to be more sensitive than other markers.Reference Banks, Frierson, Mills, George, Zarbo and Swanson6, Reference Wieneke, Thompson and Wenig45

In our study, immunostaining for 34βE12, for KL1 (an antibody specific for high molecular weight cytokeratins 1, 5, 10 and 14) and for MNF 116 (an antibody specific for these same high molecular weight cytokeratins) all had the same sensitivity in detecting basaloid SCC (100 per cent).

Immunoreactivity for S100 protein was irregularly present in our study (being seen in 17 per cent of tested patients, as compared with 39 per cent in Banks and colleagues’ studyReference Banks, Frierson, Mills, George, Zarbo and Swanson6 and 43 per cent in Wieneke and colleagues’ study).Reference Wieneke, Thompson and Wenig45

Synaptophysin and chromogranin are present in small cell undifferentiated carcinoma but are classically absent in basaloid SCC, generally permitting differentiation of these two (otherwise quite similar) lesions; however, we observed immunopositivity for both substances in 14 per cent of our basaloid SCC patients.Reference Banks, Frierson, Mills, George, Zarbo and Swanson6, Reference Wieneke, Thompson and Wenig45 A finding of immunonegativity for chromogranin and synaptophysin together with immunopositivity for 34βE12 can eliminate neuroendocrine tumour from the differential diagnosis.Reference Wieneke, Thompson and Wenig45, Reference Morice and Ferreiro48

Other antibodies have been reported to be present in basaloid SCC. Coletta et al. Reference Coletta, Almeida and Vargas53 have reported strong immunoreactivity for the anti cytokeratin 14 antibody but immunonegativity for cytokeratin 7, and immunoreactivity for cytokeratin 1 only in the squamous component of the tumour. Lack of cytokeratin 7 expression can exclude adenoid cystic carcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma from the differential diagnosis.Reference Altrabulsi, Carrizo and Luna49, Reference Kleist, Bankau, Lorenz, Jäger and Poetsch54, Reference Coletta, Cotrim and Villalba55 Lack of cytokeratin 14 expression eliminates neuroendocrine carcinomas and small cell undifferentiated carcinomas from the differential diagnosis.Reference Coletta, Almeida and Vargas53, Reference Sturm, Lantuéjoul, Laverrière, Papotti, Brichon and Brambilla56 Immunoreactivity for cytokeratin 1 indicates a squamous component, which is indispensable for the diagnosis of basaloid SCC.Reference Coletta, Almeida and Vargas53 Immunopositivity for 34βE12 and cytokeratin 14 together with immunonegativity for chromogranin, synaptophysin and cytokeratin 7 appears to be a very useful tool for the diagnosis of basaloid SCC.

Immunoreactivity to KL1 and MNF 116 also appears to be useful, but further evaluation is required.

Treatment

In all the studies cited, head and neck basaloid SCC was associated with a poor prognosis, due to a clinical course characterised by a high incidence of cervical lymph node metastasis, local recurrence and distant metastasis.Reference Ide, Shimoyama, Horie and Kusama24, Reference Tsang, Chan, Lee, Leung and Fu36, Reference Soriano, Faure, Lantuejoul, Reyt, Bolla and Brambilla51, Reference Kleist, Bankau, Lorenz, Jäger and Poetsch54, Reference Regauer, Beham and Mannweiler57 In our experience, head and neck basaloid SCC had a worse prognosis than conventional SCC, with a five-year survival rate of 5 per cent. Soriano et al. Reference Soriano, Righini, Faure, Lantuejoul, Colonna and Bolla2 compared basaloid SCC patients with a cross-matched population of patients with well to moderately differentiated conventional SCC, and concluded that basaloid SCC patients were a high risk population.

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma metastasis occurs via lymphatic and blood vessels to lymph nodes and viscera, including the lungs, bone, skin and brain.Reference Wain, Kier, Vollmer and Bossen1, Reference Banks, Frierson, Mills, George, Zarbo and Swanson6, Reference Raslan, Barnes, Kraus, Contis, Killeen and Kapadia12, Reference Ferlito, Devaney and Rinaldo15 Most basaloid SCC recurrence appears in the first year after treatment.Reference Wain, Kier, Vollmer and Bossen1, Reference Raslan, Barnes, Kraus, Contis, Killeen and Kapadia12, Reference Ferlito, Devaney and Rinaldo15 Our series confirmed this poor outcome, with a 78 per cent one-year survival rate and a poor, 22 per cent three-year survival rate. However, other authors believe the prognosis for basaloid SCC patients to be similar to that for conventional SCC patients.Reference Luna, El Naggar, Parichatikanond, Weber and Batsakis8, Reference Coletta, Cotrim and Villalba55

Some of our patients had synchronous basaloid SCC lesions. This previously unreported finding generates some questions. Do such synchronous lesions represent ‘skip’ or distant metastases from the primary? Furthermore, will some patients always develop SCC of the basaloid type?

Our results appear to confirm the aggressive course of basaloid SCC, as reported by several other authors. Our findings may assist the development of more accurate diagnostic techniques and more appropriate treatment. Currently, a new patient with diagnosed basaloid SCC, whose health status is good, will receive maximum combined treatment involving surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

• Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is an uncommon lesion in the head and neck

• This tumour has a more aggressive clinical course than conventional SCC, with rapid and frequent local recurrence and cervical lymph node and/or distant metastases

• Diagnosis is challenging due to similarity with adenoid cystic carcinoma and small cell undifferentiated carcinoma

• Aggressive, multimodality treatment is usually needed

• Careful monitoring is important due to the tumour's aggressive course

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma is an uncommon lesion with a challenging histological diagnosis. Careful monitoring is vital due to the aggressive clinical course and the necessity of multimodality treatment.

Conclusion

Basaloid SCC is an uncommon lesion which usually presents clinically at a late stage. Our study findings indicated epidemiological and histopathological parameters similar to those for conventional SCC, but a more aggressive clinical course, with rapid and frequent local recurrence and/or cervical lymph node and visceral metastasis.

The histopathological diagnosis of basaloid SCC is challenging due to this tumour's similarity with adenoid cystic carcinoma and small cell undifferentiated carcinoma. Immunostaining techniques may be very useful in distinguishing basaloid SCC from other, similar lesions; immunostaining is positive for 34βE12 and negative for synaptophysin and chromogranin.

Aggressive, multimodality treatment is required involving surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

The survival rate for basaloid SCC is clearly worse than that for conventional SCC. Careful monitoring is essential due to the tumour's aggressive course.

Acknowledgements

We thank Richard Medeiros, Rouen University Hospital Medical Editor, for editing the manuscript, and Xavier Burbaud MD, Rouen University Hospital, for initiating this work.